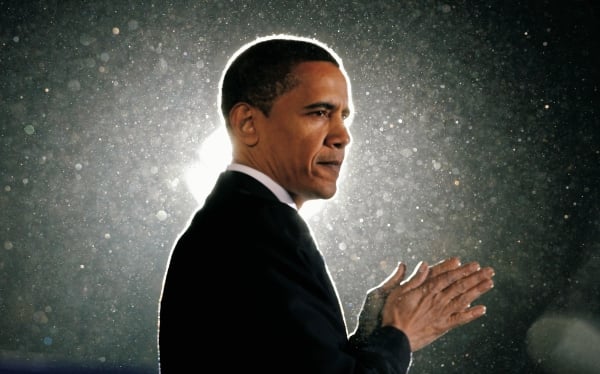

When he lifts his hand to take the oath of office, Barack Hussein Obama will set himself apart from every president who came before. His breakthrough, more profound than John F. Kennedy’s overcoming religious bigotry in 1960, was removing the whites only sign from the Oval Office.

His achievement resonates not only in this country but around the globe. Americans like to think of their president as the leader of the free world, and Washington now is the political capital of a planet drawn ever more tightly together by the same revolutionary web that helped propel Obama to the White House. As a result, he is a cultural phenomenon on a worldwide scale.

“Obama has Day-Gloed the entire world,” says Douglas Brinkley, a presidential historian at Rice University. “He’s telling the whole world it doesn’t matter if you grew up poor or had dark skin. You can be a world leader. That translates not just to Kenya or Indonesia but to Pakistan and Colombia and beyond.”

France’s foreign minister, Bernard Kouchner, the latest in a long line of shrewd visitors to Washington from that country, remarked that in 2008 Americans held “a world election.”

At the same time, the President-elect, shaped by international forces in his personal life, has a quintessential American story, one of hard work and self-made success and the nation’s eternal lure to strivers from other lands.

By electing a member of a minority group president—something that would be out of the question in many other countries—Americans lived up to their political values in a highly visible way.

Obama had argued that such a basic yet big step would enhance America’s image in the battle for hearts and minds around the globe. And he now has the opportunity to capitalize on the good will unleashed by his election.

Obama and Hillary Rodham Clinton, his secretary of State, will be America’s new faces to the world. The “new dawn of American leadership” that Obama is promising includes an intention to reach out to longtime adversaries such as Iran. “The music’s going to change. The process is going to change. The faces attached to American diplomacy will change. And people in other countries are going to be falling all over one another to give us the benefit of the doubt,” says Aaron David Miller, a public-policy scholar at the Woodrow Wilson Center who has advised Republican and Democratic secretaries of State. “The fact that Barack Obama knows the world is a complicated place, that he can be empathetic and has a sense of nuance and context, is all very important.” He also cautions that the new administration will face a major challenge in meeting extraordinary expectations.

Obama’s rise was in large part the work of a generation of young voters whose lives were stamped by the September 11 attacks, much as the Kennedy assassination altered their parents’ universe.

Young adults, many still in their teens, ran Obama’s campaign at the grassroots. Their generation turned out in record numbers and will be at the center of much of what he does as president. They are the people, as the Pew Research Center has noted, who have “grown up with personal computers, cell phones, and the Internet and are now taking their place in a world where the only constant is rapid change.”

Generation Next, as Pew called them, sees that world very differently from the way their parents and grandparents do. In what Democratic pollster Peter Hart called a transformational election, they went for Obama by an unprecedented margin. Those under 30—the most diverse voters in US history—preferred Obama by better than 2 to 1, and they were the only age group of whites to give him a majority of its votes. Just as JFK’s New Frontier marked the passing of the torch to the generation that came of age in World War II, Barack Obama’s Next Frontier belongs to them.

At home, the Obama generation is strongly inclined toward public service. The onetime community organizer headed for the White House promises to make volunteerism “a cause of my presidency.” He envisions big increases in government-sponsored volunteer agencies. But the real measure of his impact may be felt in years to come, as those who cut their teeth on politics in his campaign become the political leaders of tomorrow.

He’s already inspired a legion of young people, from Tobacco Road in North Carolina to remote reaches of the Far East. News of his election was cheered not only in the Jakarta elementary school he once attended and the Kenyan village where his relatives live but also in streets and cafes on every continent.

A 16-year-old girl from a provincial Chinese city more than 1,000 miles from Beijing e-mailed an American friend: “We like his energy, enthusiasm, youth, and his speech! We watched his speech when he won the presidential election, it’s moving and encouraging!”

Obama symbolizes the diversity of 21st-century America like no previous leader and in ways that go beyond his biracial heritage.

Bill Clinton advertised his plan to put together a Cabinet that looked like America. Obama quietly set about fashioning an administration that looks like him. The similarities go deeper than the large number of minorities. Obama’s team shares many of his personal characteristics, from his unflappability to an outward-looking perspective on the world.

In his universe, high intelligence is the coin of the realm—and a background as a global citizen is a definite plus. It’s no surprise that Virginia governor Tim Kaine is one of his favorite politicians. Kaine, like Obama, made it to Harvard Law from Middle America and had his eyes opened by life experiences outside the United States.

Obama—shaped by the polyglot society of his native Hawaii, an Indonesian childhood, and blood ties to Africa—is clearly attracted to worldly achievers. In Timothy Geithner, he chose a Treasury secretary of his own age—47—who spent formative years in Africa, Tokyo, New Delhi, and Bangkok. His national-security adviser, retired general James L. Jones, grew up in France.

The top echelon of his administration will be heavy with savvy government veterans. Conservative columnist David Brooks praised them as “the best of the Washington insiders.” Obama’s economic team, which likely holds the success or failure of his presidency in its hands, has been described as representing a generational shift.

Obama is the first president born after Kennedy took office; his parents married less than two weeks after JFK was sworn in, and he was born six months later. And yet, for many reasons, the new administration harks back to Camelot.

As president he’ll be tastemaker in chief, and his choices will likely become magnified as Kennedy’s were. His cosmopolitan style reflects modern, urban America in a way never seen before in Washington. Obama’s musical tastes are decidedly old school, according to Rolling Stone. As a product of the end of the baby-boom generation, he has programmed his iPod with artists popular in the 1970s: Stevie Wonder, Bob Dylan, Bruce Springsteen.

But he has also formed personal connections with alt-country singer Jeff Tweedy of Chicago-based Wilco and hip-hop artists such as Jay-Z. The rapper Will.i.am, frontman for the Black Eyed Peas, was among the warm-up acts for his acceptance speech in a Denver stadium. It wouldn’t be a surprise if Obama showcases the contemporary African-American scene at formal events in the East Room.

His reputation as a gym rat, along with an obsession with eating right and keeping fit—despite long years as a smoker—figure to make his pickup basketball games a focus of national attention, much like the Kennedy clan’s touch football. Whom the six-foot-two Obama crashes the boards with may generate media coverage worldwide, now that basketball is the most popular US sport outside this country.

Hopes are higher for Obama than for any incoming administration in decades. According to a Gallup poll, two of every three adult Americans think the country will be better after four years of his leadership.

“Millions of people watching this driving, handsome young man believed that he could change things, move things, that their personal problems would somehow be different, lighter, easier with his election.” That was JFK, described by David Halberstam in The Best and the Brightest.

Almost half a century ago, the nation’s aspirations for its new president seemed more extravagant than ever. Kennedy, he wrote, “was faced with that great gap of any modern politician, but perhaps greatest in contemporary America: the gap between the new unbelievable velocity of modern life which can send information and images hurtling through the air onto the television screen, exciting desires and appetites, changing mores almost overnight, and the slowness of traditional governmental institutions produced by ideas and laws of another era, bound in normal bureaucratic red tape and traditional seniority.”

For Obama, that expectations gap has widened. Worldwide communications, instantaneous and ubiquitous, have ratcheted up to levels unimaginable back in the days of black-and-white TV and three broadcast networks. Some Obama advisers worry that the public is bound to grow disillusioned, its patience worn down faster than ever by a 24-hour cable-news cycle that drives media coverage.

The inaugural address is typically a president’s first big chance to shape perceptions, and an online world will be watching Obama deliver his. There may be an echo of Kennedy’s eloquence when the first television president advised Americans to “ask not what your country can do for you; ask what you can do for your country.”

Obama, our first global president, didn’t wait for January 20 to convey a similar idea in simpler terms. He started on the day he was elected. From Grant Park in Chicago, he told everyone who was listening, “I need your help.”