On a muggy afternoon in summer 1986, I made my way across the Butler Aviation tarmac at National Airport to board my father’s JetStar II, bound for Martha’s Vineyard. I called his four-engine, nine-passenger jet Air Big Bear. As a kid I’d adored the Little Bear books by Else Holmelund Minarik. They were a bedtime favorite, and after countless readings I began calling my father Big Bear. Washington knew him as Edward Bennett Williams, the lawyer who owned the Redskins and Baltimore Orioles.

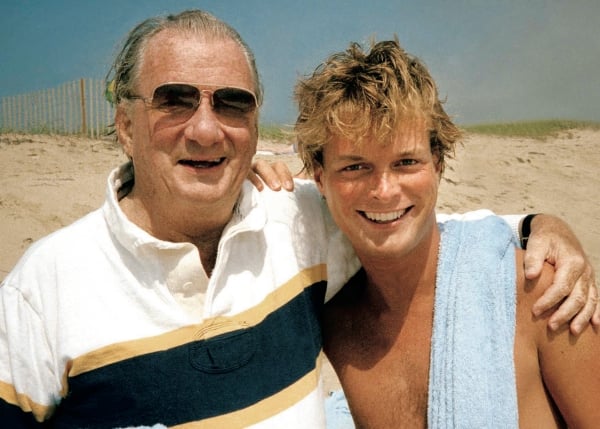

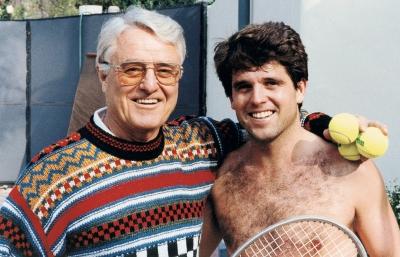

Traveling with us were Sargent Shriver and his son Mark. Sarge had phoned to ask for a ride to Cape Cod. Big Bear’s life wasn’t one of detours, but he loved Sarge, and Mark and I had been friends since first grade. A Hyannis Port drop-off was added to the flight plan.

Seven weeks out of college, I was eager to start a TV career. Mark—whose father was the first Peace Corps head and whose mother, Eunice, is one of JFK’s sisters—was interested in his family’s business: public service. My father was beginning the final 24 months of his 11-year battle with cancer, and Sarge was still some years away from an Alzheimer’s diagnosis.

And so it was on this day: two fathers, two sons heading to the beach for the weekend. Somewhere over Delaware and halfway through their first cocktail, the elders decided to impart some wisdom to the young graduates.

The conversation remains vivid. With Reagan in the second year of his second term and headlines about how his administration was mortgaging our future with $100-billion deficits, Sarge—who’d been George McGovern’s running mate in the 1972 presidential campaign—had a warning: “The country is heading toward deep trouble.”

My father, whose intuition seemed to work nicely on juries over the years, went further. He feared that our indifference to a historic deficit had cut dangerously into America’s psyche: If the government can spend significantly beyond its means, people might think, why can’t everyone else?

The poor kid from Hartford, Connecticut, was holding court in his airplane, Mark and I were his jury, and he made his case using his masterful theatrics: “This recklessness—this indifference—will lead to an economic collapse of historic proportions. It could easily ricochet around the globe!” He was just warming up. “This won’t happen in my or Sarge’s lifetime, but you two will witness the meltdown firsthand!”

With the Big Bear’s voice roaring, the flight attendant came running from the galley, concerned something bad was happening. Mark and I scoffed. We were young and optimistic and couldn’t buy their aged doomsaying.

Sarge finally said, “A prophet is not recognized in his own land.”

Admittedly, the Reagan years had been good to all those onboard. The Shrivers were finishing construction on their seven-acre, 16,000-square-foot Potomac estate, and some might say my family had managed a transition from limousine liberals to Learjet liberals.

Today, with real estate and Wall Street plummeting, I often think back to that flight. Twenty-three years later and from 30,000 feet lower, the sizzling ’80s seem like a lifetime ago. But I can still hear the Big Bear’s roar and Sarge’s dire words. Maybe the old guys knew what they were talking about.

Sarge Shriver did live to see this meltdown. He turns 94 this year. His Potomac estate is on the market for $9.9 million. Mark and I are in constant communication, with much of our conversation about our diminishing finances.

As Wall Street’s bulls fell silent last summer and the stock market began its plunge, we quietly marked the 20th anniversary of Big Bear’s death. The irony of his nickname is not lost on any of us.

This article first appeared in the April 2009 issue of The Washingtonian. For more articles from that issue, click here.