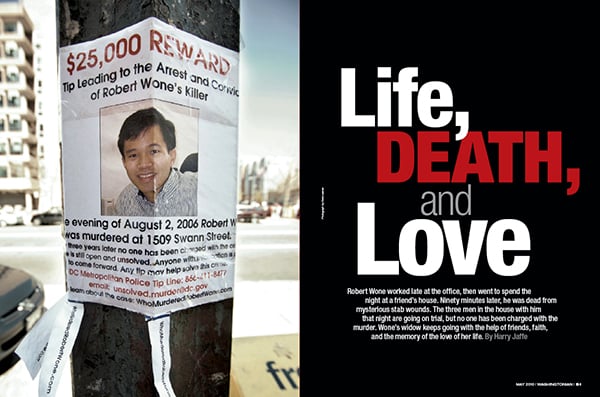

Robert Wone worked late at the office, then went to spend the night at a friend’s house. Ninety minutes later, he was dead from three stab wounds. The three men in the house with him that night are scheduled to go on trial May 10, but no one has been charged with the murder.

Harry Jaffe’s gripping tale of this confounding crime delves into the lives changed forever by the murder. In exclusive interviews, Robert’s widow, Kathy, describes their romance, their lives together, and how she’s tried to piece her life back together. The suspects, the the lawyers and Wone's friends come alive on the pages.

Read on and see what you think about who murdered Robert Wone.

Robert Wone’s last words to his wife were “I love you.”

It was 9:30 on the night of August 2, 2006. Robert Wone, general counsel for Radio Free Asia, called his wife, Kathy, on his cell phone and told her he was on his way back to his office on M Street in downtown DC. He was new in the job and wanted to meet the radio jocks who worked the night shift. Rather than take Metro all the way home to Oakton, he planned to stay in DC near Dupont Circle at the home of his old friend Joe Price.

“Have a good night,” Wone told her.

Price and Wone had been friends since their days at the College of William & Mary in the mid-1990s. Price had given Wone and his parents their first tour of the campus. The two young men shared a passion for politics and student government. Price, three years older, became Wone’s mentor and collaborator on campus projects.

Price graduated and earned a law degree at the University of Virginia. Wone got his at the University of Pennsylvania. Both went to work at white-shoe law firms in Washington. Price became a partner at Arent Fox; Wone worked at Covington & Burling before moving to Radio Free Asia. They were part of a tightly knit group of friends from William & Mary.

Price and Wone remained close, though their personal lives were very different. Price lived with two men in a three-way relationship; Wone was straight—he and Kathy married in 2003.

“I loved being his wife,” Kathy Wone says.

Wone arrived at Price’s home at 1509 Swann Street, Northwest, around 10:30. About 90 minutes later, Kathy got another call—this one from Price.

He told her Robert had been stabbed and was being taken to George Washington University Hospital.

Kathy called Robert’s parents, who had moved to Northern Virginia from Brooklyn that March to be near their son and daughter-in-law. They sped to George Washington University Hospital in Foggy Bottom. When they arrived, they learned Robert had been pronounced dead at 12:25 am.

That Robert Wone suffered three stab wounds is one of the few certainties about his death.

Two paramedics arrived at the Swann Street house five minutes and 40 seconds after a 911 dispatcher received a call about the stabbing at 11:49. They found Wone lying on his back on a pullout couch in a second-floor guest room. He was wearing a gray William & Mary T-shirt, gym shorts, and underwear. He had been stabbed three times in the chest. One thrust had pierced his heart. The slits were precise and clean. There was little blood on Wone, a few spots on the bed.

It appeared that the body had been “showered, redressed, and placed in the bed,” one paramedic reported.

Joe Price was sitting on the bed wearing a pair of white briefs.

“What’s going on?” the paramedic asked.

“I heard a scream,” Price said. He got up and walked away from the bed.

A knife was on the bedside table, but it might not have been the murder weapon.

Paramedics and police found Price’s two housemates looking showered and dressed in white bathrobes. One was talking on a cell phone. The paramedics asked, “What’s going on?” Neither replied.

Police took Price and his housemates, Victor Zaborsky and Dylan Ward, to the bunker-like homicide headquarters across the Anacostia River. Detectives put them in separate rooms and questioned them until dawn. In oddly clinical terms, each said an intruder had entered the house, stabbed Robert Wone, and left.

“I know it sounds crazy,” Price told detectives. “In fact, if you told me this and I wasn’t in this place all night, I would say, ‘No way, it cannot happen—that’s crazy.’ But damned if it didn’t.”

The detectives used standard interrogation techniques to try to wring a confession. They told each housemate the others had told a different story. None of them budged.

For nearly four years, DC homicide detectives, the FBI, and federal prosecutors have been seeking clues and answers. The basic facts of the case haven’t changed. But officials have no motive, no murder weapon, one vial of blood, suspects but no murderer.

Joe Price and his two housemates are scheduled to go to trial May 10 in DC Superior Court. Prosecutors have charged them with evidence tampering, obstruction of an investigation, and conspiracy.

Was the murder of Robert Wone a perfect crime? We may never know exactly what happened that night on Swann Street. We’re left with the tragedy of Wone’s killing—an unexplained act of violence that has tested the power of friendship and brought out the best in some prominent Washington figures. It has forced Kathy Wone to search for the beauty of the human spirit after the love of her life was taken away.

“Right after Robert died, my world was blown into so many pieces—not even pieces but mountains of ash,” she told me in one of two exclusive interviews about her life with Robert; she declined to talk about the pending cases. “I wondered: Is there even really a finish line to putting one’s life back together?”

Robert Eric Wone met Katherine Ellen Yu in January 2002 at an American Bar Association conference in Philadelphia. She was working for the ABA in Chicago; Robert was with Covington & Burling’s real-estate practice but also was working on a side project to expand opportunities for minorities in judicial clerkships. Kathy’s boss had asked her to e-mail Robert and invite him to be a panelist. They spoke by phone. Hmmm, she thought, he has a nice voice. He accepted.

At the conference, she saw him across the room. “He was a really good-looking guy,” she recalls. She was shy but found a reason to introduce herself the second day. At the end of the session, he sought her out.

“We just kept talking,” she says. “When you like someone, talk comes easily. We talked for hours—right through dinner, until midnight.”

A few weeks later, Kathy had to travel to DC. It was Valentine’s Day. The two planned to have dinner at Mimi’s on P Street. She wanted to give him something special but not intimate. She settled on a photo album of Chicago pictures with notes about places that were special to her.

They met before dinner at Covington & Burling, at 12th Street and Pennsylvania Avenue between the White House and Capitol. She gave him the photo album. He had bought a box of Godiva chocolates he’d planned to give her after dinner—if it went well. He offered it right there. She opened the envelope and read the note in his scrawl. It was hard to decipher.

“Where to from here?” he wrote at the end. “I’m not certain—but I am excited to find out if you are.”

She looked up at him.

“I’d like that,” she said. “I really like you a lot.”

By all accounts, Robert Wone had a full and rewarding life. He’d grown up in Brooklyn, the elder son of William and Aimee Wone. The first Wones had come to New York in the late 1930s from China. Robert would tell stories of his grandmother pulling him along through Brooklyn as she shopped for food. His father worked as a technology executive at Chase Manhattan Bank; his mother was a school librarian.

The family lived in a townhouse in Sheepshead Bay. Robert was small but determined on the athletic field. “Robert was a wonderful young man,” recalls Jim Graham, director of the church baseball programs. “Pleasant, very talented, and an excellent student.” He was a Mets fan. He and his father and younger brother, Andrew, would bring Aimee to Shea Stadium.

One day when Robert was 15, Chuck Schumer knocked on the door. Now New York’s senior US senator, Schumer was campaigning for reelection to the House of Representatives. Robert was so excited that he volunteered to knock on doors with Schumer. A few summers later, he worked for then-governor Mario Cuomo.

Robert attended Xaverian High, a Catholic prep school in Brooklyn. He did well enough to be named a Monroe Scholar, one of the top applicants to William & Mary, where he excelled.

Tara Ragone met Robert Wone late in their sophomore year at William & Mary. Both had been named President’s Aides, a small group that advises the school administration on college life.

“I really want to get to know you,” Robert told her. They chatted. Ragone realized he was networking and planning for their next meeting when most kids were barely getting to class on time. He came off as genuine and deep.

Is this guy too good to be true? she wondered.

She and many others who came in contact with Robert got the same feeling. He drew Ragone into his circle.

“He kept tabs on his friends,” says Ragone, now an attorney in New Jersey. “He never looked for recognition. He was always the man behind the curtain, making magic. He also had a silly side.”

Robert would put change into expired parking meters as he walked down the street. When funds ran out for campus beautification, he bought sod for the quad.

“When other kids were getting drunk on Saturday night, he was laying down new sod,” she says. “When the sculpture of a phoenix on campus was coated in bird droppings, he and some friends went out one night and scrubbed it clean.”

Robert learned that retired William & Mary president Davis Young Paschall was living alone near campus, suffering from spinal arthritis and unable to get around well. Robert went to see him and found he was brimming with stories of his days at the college’s helm. The young student took it upon himself to bring a few undergraduates over for weekly visits. It was Robert’s version of Tuesdays With Morrie.

Among William & Mary’s traditions was the 13 Club, a secret society that met to do anonymous acts of generosity. It had gone fallow. With Joe Price and others, Robert brought it back to life. He brought friends into the society, among them Michelle Kang, Lisa Goddard, and Jonas Geissler. The group stayed in touch, meeting often since college.

“Robert was the hub,” Ragone says.

And the glue. Robert had a spreadsheet with everyone’s birthdays and rarely missed sending a card. When Jonas Geissler’s first marriage ended, he called his parents first, then Robert—and broke down on the phone. A few weeks later, Robert showed up with Jason Torchinsky to help settle Geissler into his new apartment. “Robert pieced me back together,” says Geissler.

When Tara Ragone was in law school and pregnant with her first child, Wone would call to cheer her on. She returned the favor as he fell in love.

“When he met Kathy, it was dramatic,” she says. “He was crazy about her from the beginning.”

After their Valentine’s Day dinner, Robert and Kathy began a long-distance relationship. “He called every night at 8,” she says.

They flew back and forth three times a month. They took long walks on Chicago’s Lake Shore Drive. Robert took her to his favorite Washington haunts.

In March, he asked her to go with him and his parents on a monthlong trip to China in October. Kathy tried to laugh it off. “That’s a long way off,” she said. “What happens if we break up?

Kathy was a practical sort. She had grown up in Vernon Hills, Illinois, 40 miles north of Chicago. Her parents and brother had emigrated to the United States from Korea in 1971; at the time, her mother was pregnant with Kathy. Her father worked in a dental lab; her mother was a nurse. She went to public school and played the piano. She got her undergraduate degree from the University of Illinois and her law degree from Saint Louis University in 1996.

Kathy had been diagnosed with lupus in junior high. She told Robert early in their relationship and was prepared to get a call saying their love affair was over. Instead, he invited her to China.

She weighed the pros and cons. She loved Robert’s intelligence, admired his patience and generosity. While holding down his job at Covington, he was active in the Asian Pacific Bar Association, served on the Virginia Governor’s Commission on Community and National Service, and was the volunteer general counsel of both the Organization of Chinese Americans and the Museum of Chinese in America.

“And,” Kathy says, “he was a gentleman. From day one, I never opened a door when I was with him. He was always encouraging, nurturing, and protective of me.”

She accepted the invitation to China.

In June of that year, they were walking along Chicago’s Lake Shore Drive.

“What do you think our wedding invitation will look like?” he asked.

She kept walking and calmly described it to him. It would have to have a Chinese double happiness symbol. He agreed. Then they stopped, faced each other, and laughed.

“Oh, my gosh,” she said. “We’re going to get married.”

They talked about what kind of ring she wanted and when they might have the wedding. She had one request: “When you propose, you must surprise me.”

The China trip was arduous but a success. They sent hundreds of photographs to friends and family. Then they flew back, stopping first in Chicago.

When they arrived at Kathy’s condo, Robert had to pay the cabbie and carry her luggage up a flight of stairs. “You go on up,” he said.

When she opened her apartment door, she saw a trail of rose petals, which led to a bouquet of long-stemmed roses. On her dining-room table was a plate of fresh fruit amid more petals. Next to it was a ring box and a sterling-silver fortune cookie. The tiny note inside read: “Will you marry me?”

She opened the blue Tiffany box and asked him to put the ring on her finger.

“Did I surprise you?” he asked.

Robert and Kathy were married on June 7, 2003, in Itasca, Illinois, about 26 miles northwest of Chicago. Federal judge Raymond Jackson, for whom Robert had clerked after law school, officiated.

The William & Mary gang showed up in force, as did friends from law school and new ones from Washington. Joe Price flew out with his partner, Victor Zaborsky. Tara Ragone, Michelle Kang, and Jonas Geissler all came.

Kathy moved into Robert’s apartment in Arlington and landed a job first with the Bureau of National Affairs, then with a health-care consulting firm. In July 2004, they bought a townhouse in Oakton.

They had an active social life that revolved mostly around Robert’s friends from William & Mary and people in the Asian-American legal community. While Robert was at Covington, they settled into a routine: Kathy would get home around 6, then pick Robert up at the Metro, usually around 8.

Their friends were having babies; they talked about having kids, but when Kathy suffered her worst bout of lupus in high school, doctors had told her that having children might threaten her life. Still, she and Robert often discussed the topic until he put it to rest.

“It took my whole life to find you,” he said. “Why would I want to endanger your health for anything?”

They were warming up to the idea of adopting a daughter from China.

“That’s where our marriage was headed,” Kathy says.

Robert Wone’s 30th birthday celebration in June 2004 was at Joe Price’s house on Capitol Hill. The William & Mary gang was there. One friend had had a painting made with six portraits of Robert, Andy Warhol style.

“It meant a lot to me that Robert had so many close friends,” says Kathy. “It was a core group that I wanted him to keep and nurture.”

In some ways, Robert Wone and Joe Price were similar—both highly driven, accomplished attorneys, devoted to causes.

Price focused his volunteerism on gay rights and became a leading voice in the movement. He had grown up in a military family. His father was a career Navy petty officer, and the family moved from Texas to Japan to the Florida Keys to Cape Cod. Price was an Eagle Scout; he doted on his sister and his younger brother, Michael.

At William & Mary, Price was president of the student assembly and graduated in 1993 with a degree in public policy. After law school at the University of Virginia, he became president of the UVa Gay and Lesbian Alumni Association.

A talented lawyer, Price clerked for US District Court judge Norman Moon in Virginia. Recruited by Arent Fox, Price joined the firm in 1998 and became a partner in 2006. He specialized in intellectual-property litigation and argued cases in federal court for clients such as AOL and the Mars candy company.

On his own time, Price helped found Equality Virginia, an advocacy group for gay, lesbian, bisexual, and transgendered Virginians. He represented Janet Jenkins in a landmark custody battle over the child she had with Lisa Miller in a case that the Supreme Court ultimately declined to hear.

Price and Victor Zaborsky have lived in a committed relationship for years. Together they had sons with a lesbian couple in Silver Spring—Price fathered one, Zaborsky the other.

“We are forging new territory here,” Zaborsky told a USA Today reporter in 2004. “There are no role models.”

Price and Zaborsky had renovated a Capitol Hill rowhouse, knocking down first-floor walls to create an open party space. They invited friends for Saturday-night parties and Sunday brunches. Often on hand were the lesbian moms and children from Silver Spring; Joe’s brother, Michael, also gay; Sarah Morgan, a tenant Price considered family; and Dylan Ward, a roommate who would become Price’s lover.

“Joe was the patriarch of that family,” says a friend. “He reveled in gathering everyone he considered part of that family, with him at the center. They were good at entertaining. Victor would cook. Joe would keep the conversation flowing. It seemed like everyone in the gay community knew Joe or knew someone who knew him.”

Photos of Robert Wone’s 30th birthday show him surrounded by Joe Price, Dylan Ward, and Victor Zaborsky. Ward is holding a birthday cake with candles. Everyone is smiling.

“That was the good Joe,” says the friend.

Price and his housemates would soon sell the Capitol Hill house and move to Swann Street near Dupont Circle.

Mai Fernandez, codirector of the Latin American Youth Center, had a problem in late 2004. Her organization had bought some rundown buildings in DC’s Columbia Heights, and she was trying to convert them to houses for homeless teenagers. She had lined up an architect and a builder but had run into a wall of zoning problems.

“I called Robert,” she says. “He worked through the problems until all the houses were converted.”

Robert’s work for the Latin youth group was one of his many volunteer projects. After his clerkship with Judge Jackson, he had weighed offers from Washington law firms. He had been a summer associate at Akin Gump and could have worked there. He chose Covington & Burling in part because he knew it had a vibrant pro bono practice. While keeping up with paying real-estate clients, Robert was able to donate time and expertise to the Organization of Chinese Americans and the Academy of Construction & Design at Cardozo Senior High School. He took a leadership position with DC’s Asian Pacific American Bar Association and was in line to be its president.

The Latin youth group works with an estimated 4,000 kids a year in DC and Maryland. Before Robert helped solve the housing problems, he wrote the organization’s personnel manual and worked pro bono for the group.

“Robert became my go-to guy,” says Fernandez. “No matter what it was, he had time to help—law, real estate, personnel. Not a week went by that I didn’t call him. He was like my Batphone. No matter what the issue, he would help me think it through.”

By 2005, the converted buildings housed children who needed a roof over their heads.

In the early summer of 2006, Robert saw an ad for a job as general counsel at Radio Free Asia, a nonprofit that broadcasts news and information to Asia. He was doing well at Covington but yearned for a new challenge. He applied, went through the interviews, and was hired.

“We struggled with the decision,” says Kathy. “We knew he was going to take a huge pay cut.”

Robert made sure his wife was on board. “I don’t need to drive a Lexus,” she told him. “I’m happy with our Honda. I want you to be happy. Go for it.”

Robert immersed himself in the new work. He started boning up on international communications law. He got to know the staff.

“He really loved it,” says Kathy.

After work on Wednesday, August 2, he met with John Lindberg, general counsel at Radio Free Europe. They had a quick sandwich for dinner and then attended a legal seminar. At about 9:30, Robert headed back to the office to get acquainted with the night staff. On the way, he phoned Kathy.

About an hour later, he made his way to 1509 Swann Street to spend the night.

He arrived at about 10:30. Price and his housemates, Zaborsky and Ward, were at home.

What happened during the next 79 minutes remains unknown to any but those in the house.

Price and Ward told police they welcomed Robert into the kitchen and sat around the table sipping water. Zaborsky told police he was in his bedroom watching Project Runway. Price and Ward then led Wone to a guest room on the second floor. A convertible couch had been pulled out for him. Ward told police he went to his room on the same floor and took a sleeping pill; as he dozed off, he heard Robert taking a shower. Price and Zaborsky told police they retired to their bedroom on the third floor.

That accounts for events until about 11 pm. In the following 45 minutes, Price said, he heard the security system’s chimes at the back door. Zaborsky said he heard one low scream, then another. They said they discovered Wone mortally wounded on the guest-room bed.

By their combined accounts, someone had stabbed Robert Wone and left the house. They did not explain who cleaned the room of blood, washed the body, discarded the murder weapon, disposed of the bloody towels or sheets, and changed the bedding—in 45 minutes.

Zaborsky phoned 911 at 11:49. “We need an ambulance,” he said. He was gasping.

“What’s wrong, ma’am?” the operator asked, mistaking Zaborsky’s voice for that of a woman.

“We had someone . . . in our house, evidently—and they stabbed somebody.”

Two paramedics arrived five minutes and 40 seconds later. Jeffrey Baker, an Emergency Medical Services worker for more than ten years, had seen dozens of crime scenes with people screaming and blood everywhere. Here there was quiet, three men looking freshly showered, and a victim with three stab wounds but little blood.

The scene “made the hair on the back of my neck stand up,” he said.

The medics gave Wone an EKG. It showed a flat line. They rushed him to the hospital.

When DC police officer Diane Durham arrived on the scene, Price—still dressed only in white briefs—did all the talking; he also gave her a different story than the one he would later tell detectives.

“He said they heard someone scream and ran downstairs to see,” Durham said. “Underwear guy said the victim was at the patio door bleeding, they opened the door, took him upstairs and laid him on the bed.”

She advised “underwear guy” to put on some clothes.

The second paramedic, Tracye Weaver, a 15-year EMS veteran, said that things in the house were “very wrong.”

Kathy Wone got home from the hospital around 4 am. Robert’s mother and aunt spent the rest of the night with her. At 7 that morning, she called Jason Torchinsky, Robert’s former roommate and longtime friend. Jason had called Robert Wednesday afternoon to tell him about his new Honda.

“Talk to you tomorrow,” Wone had said.

Torchinsky was getting ready for work. The caller ID read “Robert Wone.” He picked up the phone and greeted his friend.

“Jason, this is Kathy,” she said. “Robert was stabbed to death last night. He’s dead, Jason. Robert is dead.”

Torchinsky gasped and grew faint. “What are you talking about?” he said.

Kathy told him again. He asked if she wanted him to come to Oakton. “Not yet,” she said. Maybe in the afternoon. She asked him to call the crew. She made the same request to Michelle Kang, who called Tara Ragone at her law office in New Jersey.

“Go back and tell the doctors they are wrong!” Ragone screamed into the phone. “They have made a mistake. Robert can’t be dead.”

By Thursday afternoon, family and friends surrounded Kathy Wone in the Oakton townhouse. There was a funeral to plan.

On Friday afternoon, Joe Price, Victor Zaborsky, and Dylan Ward went to the Wone home. Kathy suggested they talk in the basement. “Want me to be with you?” Torchinsky asked. She declined.

Kathy spent more than a half hour alone with the three men. She was quivering—afraid to find out the details.

“What happened?” she asked.

They told her that they had had a glass of water with Robert and gone to sleep, that they had heard grunts, that an intruder had come into their house.

They gave her no details of how her husband might have died.

Detective Bryan Waid, a veteran DC cop, had called that afternoon and asked if he could come out and talk with Kathy. They agreed to meet on Saturday.

Waid told Kathy she could have one other person present for the interview. She asked Jason Torchinsky, a practicing attorney who had been a federal prosecutor in Milwaukee.

Detectives spent more than an hour with Kathy and Torchinsky. They wanted to know about her last conversation with her husband, his plans for the night, the call from Joe Price saying Robert had been stabbed.

The next night, Sunday, Joe Price called Torchinsky on his cell phone. Torchinsky was in the basement writing his eulogy for the Tuesday funeral. Price’s lawyers wanted to know what the detectives had asked when they’d visited with Kathy the day before. In order to get that information, Kathy would have to waive her attorney-client privilege with Torchinsky. Would he ask Kathy to let him share the conversation they’d had with the detectives?

“Let me think about it,” Torchinsky replied. He thought for less than a minute before the shock hit. Why would Price want to know what Kathy had told the police? Did he want to make sure their stories squared?

Torchinsky phoned a friend who was also a lawyer and explained the situation.

“Find her another lawyer,” the friend said. “You are too close, and you don’t know where this is going.”

In the middle of the night, the same friend e-mailed: “Contact Covington.”

On Monday morning, Jason Torchinsky e-mailed Robert Gage, the lead partner in Covington’s real-estate practice and Robert Wone’s boss for most of the six years he was at the firm. Gage was on vacation in Italy. He phoned Torchinsky from a train and asked him to send an e-mail explaining the entire situation and the sequence leading up to Joe Price’s phone call. Ten minutes later, Torchinsky got an e-mail from Eric Holder.

“I’d be glad to assist,” he wrote. Continuing, he said, “If you want me to represent Robert’s wife I can do that as well.” In an almost immediate e-mail follow up, Holder said, “I hope this goes without saying but this would of course be free of charge.”

Holder, a longtime Washingtonian, was spending a period of time in private practice. Ronald Reagan had appointed him to DC’s Superior Court bench in 1988; he stepped down in 1993 to accept an appointment by President Clinton as US Attorney for the District of Columbia. Clinton then asked him to serve as deputy attorney general in 1997. Holder left government and joined Covington & Burling in 2001.

Holder and Torchinsky talked Monday evening after the viewing for two hours. Holder—drawing from his days as chief prosecutor—asked detailed questions about the events and the people involved. He gave Torchinsky the sense that Robert Wone was considered part of the Covington family and that his widow would have the firm’s full support.

Tara Ragone drove down from New Jersey to attend Robert’s funeral on Tuesday, August 8. Columbia Baptist Church, a simple, spacious building in Falls Church, was full of people Robert had touched—in college, law school, volunteer organizations, church. More than a dozen friends who gave eulogies sat on the dais; Robert’s family was in the first pew.

A simple wooden casket held Robert’s body. Kathy had asked Joe Price to be one of the pallbearers.

Sitting in a pew, Ragone wondered how Price was handling the loss. She sympathized with him. His home had been invaded, his friend had been murdered, and people suspected him. She hugged and comforted him.

At a friend’s house after the funeral, Ragone asked a female friend: “How did the intruder get into Joe’s house?”

The friend looked at her as if she were crazy and said: “Oh, there was no intruder.”

Ragone was speechless. “Why would you think that?” she finally said. “Joe was Robert’s friend.”

The police had had doubts about the intruder story from the moment they surveyed the house and the room where they found Wone: all tidy and every object of value in place. Wone’s Movado watch and BlackBerry were still at the foot of the bed.

According to transcripts, detective Daniel Wagner posed this scenario to Price during six hours of interrogation:

“I got three homosexuals in the house and I got one straight guy. What’s he doing over there?”

Wagner answered his own question: “I think we were all drinking wine.” He filled in the trio’s thoughts about Wone: “ ‘You are coming to Jesus tonight.’ That’s what’s going on.”

After the night of questioning, the three housemates lawyered up, hiring some of the best defense attorneys in the city and communicating with authorities only through them.

Detective Bryan Waid attended the funeral and kept tabs on the housemates.

But Tara Ragone believed Price’s story. In her view, he was clearly in distress.

“I don’t think we will be arrested,” she says he told her.

“Why would you be?” she asked.

In the months that followed, little information surfaced about the case.

The day after the slaying, Captain C.V. Morris, then head of the DC police department’s Violent Crimes Branch, had told reporters in a briefing, “Some of the information we were told I just don’t believe.” Weeks later, he said: “Everybody we’d been able to talk to now has a lawyer, so there hasn’t been a lot of keeping in contact.”

Police started requesting search warrants for 1509 Swann Street the day after the stabbing. Cops guarded the door. FBI forensic experts gathered evidence, emptied bookcases, recorded computer hard drives, and generally took the house apart. They trucked away pieces of walls and staircases.

At the William & Mary homecoming that October, friends of Robert Wone organized a memorial. Many 13 Club members participated.

Joe Price and Victor Zaborsky were on campus to take part in the memorial, but the Wone family told friends they preferred that Price not attend so that the focus would be on honoring Robert. The two men stayed away.

Other than that tension, Price’s life seemed to be in order. He had continued to work at Arent Fox. He and Zaborsky and Ward moved around a bit but stayed together.

Kathy Wone’s life was falling apart.

She couldn’t stay alone in the Oakton townhouse. Her older brother stayed with her for a few weeks, but he had to return to Phoenix. She stayed with friends for the next seven months. Bills from the townhouse piled up. She didn’t care whether the bank foreclosed.

“My accomplishment of the day was getting out of bed, taking a shower, and making it to the breakfast table,” Kathy says. “The mere act of existing was almost unbearable. I was convinced I would never know happiness again.”

She sought a grief counselor.

“I wanted a Christian counselor,” Kathy says. “My faith in God and Jesus Christ has always been an anchor throughout my life. I needed to talk with someone who would really understand that, as I began the long process of working through all the confusion and pain caused by Robert’s death.”

She found the person she was looking for, began seeing her regularly in October, and still sees her. In November, she returned to work part-time at the American Health Lawyers Association.

“At first it was an exercise in physically showing up,” she says. “I got the sense that grief is so unpredictable, so dependent on the moment. I was careful about telling bosses what to expect. But work was one thing I never had to worry about. My boss said, ‘Your office will always be here. Don’t come back a moment too soon.’ ”

The friends she was staying with had three boys. In the midst of her grief, she would hear them doing everyday boy things: crashing toy trucks into walls, laughing over some TV show.

“I started to think things might be okay,” she says.

One evening, the friends invited a few people over for dinner. Everyone was seated at the table when one of the boys rushed up and asked, “Aunt Kathy, was Uncle Robert stabbed or shot?”

Guests and friends gasped. She felt relief.

“I was happy that a five-year-old was having a hard time understanding what had happened,” she says. “No child should have to know death, evil, tragedy like that. In his need to understand why Robert was not with us, I saw his innocence—that there was still good in the world.”

In the spring, she felt strong enough to move back to the house in Oakton. She adopted Buddy, a Shiba Inu dog.

“My grief is not as violent as it used to be,” she says. “I don’t break down in puddles of tears every hour like I used to. Grief is a quieter, more private experience now, a gentler emotion that is a tender-sweet reminder of what used to be and what will never be.”

News from the investigation was too quiet for Eric Holder.

Price, Zaborsky, and Ward made no public statements, but they cooperated with authorities through their attorneys. They provided DNA and fingerprints. In January 2007, they agreed to provide hair samples.

Neither prosecutors nor police had said a word publicly about a break in the case.

On August 6, 2007, a year after the murder, Holder summoned reporters to Covington & Burling. He and Kathy Wone had a few things to say. Kathy, her hair cut short, was seated at a long table when Holder arrived. He bent over, kissed her on the head, and took his seat in a room full of reporters and cameras.

Benjamin Razi, a Covington partner involved in the case from the start, introduced Kathy. She was nervous—her voice shook at first but became firmer.

“As we approached the one-year mark of Robert’s death last week,” she said, “several people asked how I was doing.” She thanked her church and friends and family.

“Slowly but surely, life has been coming back. I’m laughing again, and I’m enjoying the company of friends. I can listen to music, and this time I actually hear the notes. So I think overall I’ve done okay from having come through the darkest year of my life.”

After a pause, she asked police and the FBI to press her husband’s case. Then she spoke to her husband’s killer.

“While dealing with my own share of paralyzing sadness,” she said, “I realize that I also grieve deeply for the loss of your own life. Having a murder on your conscience is no small load to carry as you try to live, I imagine, as normal a life as possible. Confessing will be the hardest thing that you will ever do in your life. Our laws will impose severe consequences, but it will also be the most freeing thing that you can do for yourself. The secret like the one you are hiding from the world will only grow heavier with time.”

Jason Torchinsky and Eugene Chay, past president of the Asian Pacific American Bar Association, spoke. Then Eric Holder rose and pointed to a large photograph of Robert Wone. He spoke for about ten minutes.

“As despicable as that crime was and is, as big a tragedy as that is, it is compounded by the fact that Robert’s killer has not been brought to justice,” he said. “Washington, DC, is a great city, and in this case our city has not lived up to its greatness—in fact, none of us has.”

Holder talked about Robert and Kathy. Then he spoke to Joe Price and his housemates.

“For those in 1509 Swann Street, where Robert was killed,” Holder said, “you need to truly ask yourselves—truly, truly ask yourselves—have I provided the police with all the information that might be relevant to the investigation of this crime? Only you, your conscience, and your God know the answer to that question, but that is the question you must ask yourselves if you care about Robert, if you truly care about his family, if you care about Kathy—come forward and share all of the information that you have.”

No one came forward.

On October 27, 2008, prosecutors charged Dylan Ward with obstruction of justice. The affidavit in support of his arrest warrant suggested that Robert Wone had been injected with a paralytic drug, sexually assaulted, smothered, and then stabbed. It dismissed the theory that an intruder had killed Wone.

There was no way, it said, that an intruder could have scaled the rear security fence, happened upon the unlocked back door, walked through a house replete with valuable electronic devices, scaled the steps, passed the door to Ward’s room, entered the guest room, stabbed Wone, cleaned up the scene, and retraced his steps—in less than an hour.

Forensic experts had concluded that the knife beside the bed was not the murder weapon. It was covered with Wone’s blood, but the fibers on the knife weren’t from the gray T-shirt Wone wore but from a towel by the bed, which suggested the towel had been used to coat it with Wone’s blood. It was also too long to have been the murder weapon.

The actual weapon, police said, was consistent with a knife missing from a cutlery set in Dylan Ward’s room.

When deputy medical examiner Lois Goslinoski performed the autopsy, she found several needle marks, according to the affidavit: “There were multiple needle puncture marks on the left side of his neck, three needle puncture marks present in the center of his chest, two needle punctures to the upper portion of his right foot, and one needle puncture mark on the back of his left hand.”

Wone’s body showed “no defensive wounds” and no sign of struggle. “Moreover,” the affidavit said, “there was little to no blood on his hands, indicating that he did not even clutch his hands to his chest at the time of or immediately after the attack, as would be a natural human response if one were conscious/not incapacitated.”

There were only two spots of blood on the bed.

“The forensic pathologist opined that the three stab wounds were inflicted while the victim was incapacitated,” the affidavit said.

What happened to all the blood?

“The cadaver dog alert on the rear stairwell drain and the lint filter of the clothes dryer suggest that bloody clothing or items were cleaned off in the backyard stairwell and then placed in the clothes dryer to dry,” the affidavit said.

A police dog trained to detect cocaine, marijuana, and opiates was taken through the house. He “alerted” to two locations, giving handlers the suggestion that there had been drugs in the house. They recovered only Ecstasy.

Prosecutors also posited that the housemates had delayed their call to 911 for “as little as 19 minutes or as many as 49 minutes.”

The affidavit also described in detail the “three-way” relationship among the housemates. Price and Zaborsky shared a bedroom and had been in a committed relationship for years. Ward, a relative newcomer, had his own room and had a “personal, intimate” relationship with Price.

“This relationship included a dominant-submissive sexual relationship with Ward in the dominant role and Price in the submissive role,” it said, “as related by witnesses and as captured in multiple photographs of Price recovered from his computer.”

Police recovered implements of sexual bondage and torture from Dylan Ward’s room. These included racks, shackles, metal and leather collars, metal penis rings, penis vices, studded penis bindings, and an electrical shock device. There were books “relating to inflicting pain on others for purposes of sexual gratification. . . . Many of these books contained passages highlighted by the reader.”

Goslinoski and the FBI lab found Robert Wone’s semen on various parts of his body.

“The fact that Mr. Wone’s semen was found on and around his genitals, on his anus, and in his rectum is consistent with a sexual assault of some kind,” the affidavit concluded, “especially in light of the assertions of Price, Zaborsky, and Ward that Mr. Wone was heterosexual and had showered right before going to bed in the guestroom.”

Though the 13-page affidavit was full of crime-scene details and autopsy results, it did not make sense of the actual crime. With no evidence or confession, prosecutors couldn’t charge anyone with murder.

“By all accounts and evidence,” the affidavit said, “Price, Zaborsky, and Ward have a very close relationship and clearly have motive to preserve and protect the interests of one another.”

Kathy Wone was with Benjamin Razi, her attorney, when she first read the affidavit.

She hadn’t broken down in public—ever. As she read, she tried to maintain her composure. She failed.

“It was as if Robert had gotten killed all over again,” she says.

“I couldn’t stop crying.”

Glenn Kirschner was bent on getting one of the three residents of 1509 Swann Street to break ranks.

Kirschner, the lead prosecutor in the US Attorney’s homicide section, had taken over the case in February 2007 and begun to turn the screws. He had interviewed Ward and Zaborsky. The two also had agreed to testify before a grand jury investigating a burglary at the house after the murder.

The three housemates had remained together, repaired damage from the crime searches, and sold the Swann Street home in June 2008 for $1.47 million. After first moving in with Zaborsky’s aunt in McLean, Price and Zaborsky bought a home in Miami Shores, Florida, but wound up staying in an apartment in the District.

Three months before filing the affidavit and the arrest warrant for Ward, Kirschner told Ward’s attorney he intended to arrest the three. If it was an attempt to make them talk, it failed. Through their attorneys, they said they would turn themselves in.

The government obtained an arrest warrant for Dylan Ward on October 27 and arrested him two days later in Florida. He was shuttled to federal prisons and kept in custody for nearly a month.

Prosecutors thought they might turn him against his friends. A slight man, Ward was 38 at the time, the son of a cardiologist in Tacoma, Washington. He had graduated with honors from Georgetown University in 1992. He’d studied cooking, worked in publishing, moved to DC, and, thanks to Price, gotten a job raising funds for Equality Virginia. He then studied massage in Thailand. He had never been in jail. But he didn’t change his story.

While Ward was in jail, prosecutors called in Price and Zaborsky. With their attorneys, they met with prosecutors in DC. Both were told they would be arrested if they refused to cooperate with investigators. Neither talked.

Kirschner then charged Price and Zaborsky with obstruction of justice and demanded cash bonds of $100,000. They turned themselves in and went free. Price spent one night in jail while lawyers negotiated the terms of his release.

“Collectively,” Ward’s attorney, David Schertler, wrote in asking for his release, “these facts underscore the Defendants’ intent to continue to participate in good faith in the judicial process and to vigorously defend their innocence.”

Dylan Ward was freed less than a month after his arrest pending trial.

Tara Ragone was trick-or-treating with her children in Maplewood, New Jersey, on Halloween 2008 when the affidavit became public. She was wearing the Hershey’s Kisses costume she’d donned since she was in high school. Jason Torchinsky told her the news by cell phone and sent the document to her computer. She went home to read it.

For the two years since her friend was killed in her other friend’s house, she had continued to believe Joe Price’s story.

“Until I saw evidence to the contrary,” she says, “I thought Joe was not involved. I tried to play Switzerland. I asked myself: ‘Would Robert be turning on a friend before all the evidence was in?’

“Joe can be strong-willed and arrogant,” she says, “and if you get on his bad side, he might cut you off. But that doesn’t mean I can see him hurting Robert.”

She had gotten to know Victor Zaborsky through Price. He seemed a gentle soul.

“I would think he is way too sweet and pure to be involved in something so heinous,” she says, “much less able to conceal that involvement for so long.”

Ragone and Price had traded e-mails. “You can ask me anything,” he said, but she didn’t follow through. He said that insinuations that he’d been involved in Robert’s death were “pure madness.”

In one e-mail, Price wrote: “It is a true Catch-22. The police get to accuse us of not saying all we know, but we are not allowed to fully respond for fear they will retaliate by arresting one of us. Based on what we know of the investigation, it seems they were just so sure from the get go that one of us did it, they never bothered to EVER investigate the possibility of an intruder. Now that their theory that it was one of us has not panned out, they are doing their very best to cover up from the Wones and the public that they never bothered to pursue the intruder theory.”

After the one-year-anniversary press conference at which Holder asked him to come clean, Price said he was “so depressed and so angry.” Ragone suggested that Price meet with the Wone family and clear the air. He responded that he had been fighting with his lawyers about sharing information with Kathy Wone’s attorney.

Still in her Halloween costume, Ragone read the affidavit and felt herself turning from sympathetic friend to prosecuting attorney. She had to ask herself: Where’s the blood? Why the delay in calling? Why the fibers on the knife?

“The shoe dropped,” she says. “The affidavit forced us to pick a side. Given the open questions and my inability to ask Joe the questions he long ago invited, I found it impossible to keep trying to play Switzerland. I stopped making efforts to stay in touch with Joe.”

She sent one more Christmas card; her note bore a prayer for “fairness and truth.”

The affidavit was raw material for Eric Holder and Benjamin Razi. They had assembled a team of lawyers to represent Kathy Wone’s legal interests. They dissected the government’s affidavit and began developing a civil suit against the trio.

As the team worked on the case, Holder opened his office to Kathy Wone. They met whenever she asked. He rarely missed a meeting.

“He treated me as if I were the only person in the world,” she says. “He never looked at his watch.”

Covington treated her like family, she says, and helped her rebuild her life.

Barack Obama’s presidential campaign was in full swing in the fall of 2008. Wone knew Holder had a relationship with Obama and was excited that the country might have its first black President. The night Obama won, she sent Holder an e-mail that simply said: “Yay!” Holder wrote back: “Great night.”

On November 19, 2008, the government indicted Price, Zaborsky, and Ward for obstruction of justice. Price was on a leave of absence from Arent Fox to deal with his case. On November 25, Kathy Wone filed a $20-million, four-count wrongful-death suit against the three.

“The evidence suggests that, rather than administering aid to Robert Wone or making a prompt report to authorities,” the suit alleges, “Defendants spent the crucial minutes after the stabbing coordinating their stories, altering and orchestrating the crime scene, and destroying evidence.”

In the fourth count, conspiracy, it alleges: “Defendants are parties to an ongoing conspiracy that was conceived no later than the night of Robert Wone’s murder, went into effect on that night, and continues to this day.”

For such a troubling crime, there had been precious little coverage or conversation—so many unanswered questions, so many questions unasked.

How does a three-way relationship work? How could sex toys turn to torture? Could Joe Price, a gold-plated attorney and leader in the gay community, have a dark side?

“We took it upon ourselves to help figure out some of these questions,” says Craig Brownstein, one of four gay Washingtonians who created the blog Who Murdered Robert Wone? “It became our family business.”

Brownstein was celebrating his birthday with friends at Arlington’s Nam Viet restaurant in December 2008. David Greer had read the affidavit and was baffled by the case. “Not polite dinner conversation,” Brownstein says. When they returned to his rowhouse in Logan Circle, they pored over the document for three hours.

They found “an endless, bewildering puzzle,” Doug Johnson recalls, with a need for some explanation from within the gay community. “Someone needs to be talking about this. I guess it’s us.”

Brownstein is a public-relations executive with Edelman. His partner, Doug Johnson, is a journalist with Voice of America. Greer is a speechwriter for a trade association. Michael Kremin is a digital-media consultant.

“What could we do to show that the gay community is not monolithic?” Greer asked. “Some of us are evil; some of us are good.”

A few days later, Greer put up his first blog post. Kremin gradually created a sophisticated Web site. Packed with documents, it’s now a destination for journalists, lawyers, groupies, and prosecutors. Camille Paglia linked to it on Salon.com; a mention on the Drudge Report brought thousands of readers; the Village Voice’s Michael Musto supplied an audience from New York.

Brownstein and Kremin had been in a courtroom only as jurors. Now they and their collaborators attend every hearing, then post updates and video within hours. They often obtain and post every new document within hours.

It was David Greer who ferreted out DC cop Diane Durham’s crime report in which Joe Price said he first found Robert Wone’s body in the kitchen—before he changed it to the guest bedroom. They posted Price’s plea for funds for his legal defense in November 2008. They delved deeply into Price’s sexual tastes, in particular his postings on a sadomasochistic Web site, Alt.com. Price’s profile, with a photo of him wearing a chastity belt, listed his preference for caging, torture, and confinement.

“It was shocking, even to us,” says Doug Johnson.

“He put forward an image of the white-picket-fence lifestyle of a prominent attorney,” says Kremin, “but it contrasted with the other life he was living.”

Did Robert Wone spend the night at Swann Street knowing he might participate in his hosts’ extreme sexual practices?

“At first blush,” Brownstein says, “everyone makes the supposition there could have been some degree of consent. That would fill in a lot of missing pieces of the puzzle. What we know about Robert—by all evidence from within and without the gay community—does not support that.”

In the hours after the murder, one of the DC detectives asked Joe Price if he had been attracted to Robert Wone. He responded, “I don’t have any doubts Robert was, you know, is straight as the day is long.”

The four bloggers discovered that Wone’s case wasn’t listed among the DC police department’s cold cases of 2006, so they posted flyers with Wone’s photo and the reward for information. Brownstein plans to take a month’s leave to cover the May trial. They’ve petitioned the court to allow live blogging of the proceeding.

Why such dedication?

“When you see the Wone family in court, they have every reason to hate gay people,” says David Greer. “We are doing everything we can to show that what happened to Robert was not normal for gay people.

“And we’re trying to find justice for Robert. There are gay people who firmly believe justice is more important than community.”

Kathy Wone began to appreciate their efforts. When they asked readers to contribute material to commemorate the third anniversary of Robert’s death, she sent a DVD of the memorial service.

“This will help you tell Robert’s story,” she wrote.

The story of Robert Wone’s murder has developed its own narrative, characters, and plot twists, many revolving around Eric Holder. The first judge on the case, Frederick Weisberg, served on the bench with Holder. He also heard cases while Holder was US Attorney.

Shortly after the government filed its affidavit and arrest warrants, Barack Obama appointed Holder the nation’s attorney general. That made him Kirschner’s boss—again. Holder has recused himself from the case.

Judge Weisberg presided over the case until January. Coming from the public-defender service before he took the bench, Weisberg seemed to give leeway to the defense team: David Schertler for Dylan Ward, Bernard Grimm for Joe Price, and Thomas Connolly for Victor Zaborsky.

By Superior Court rules, judges rotate periodically. The judge scheduled to take over the Wone case was Lynn Leibovitz. She had come from the US Attorney’s office, where she had worked with Ward’s attorney, Schertler. In fact, Schertler had been Leibovitz’s boss.

In an unusual request, the defendants’ attorneys asked the court to keep Judge Weisberg on the case because he was familiar with its complexities. Their request was denied. Leibovitz has taken the bench and begun to move the case along with greater dispatch. One of her first rulings was to deny the defendants’ motion to dismiss certain charges. She called it “meritless.”

In one exchange on March 12, Leibovitz mentioned that she was familiar with detective Daniel Wagner. “You know I worked with him when I was a prosecutor,” the judge said. “It will not affect me. Mr. Schertler knows this especially.”

Among the most troubling aspects of the case are the many mistakes made during the initial investigation. Police technicians botched the crime-scene search. Toxicology records were discarded. The Secret Service, which is in charge of the government’s mobile devices, failed to preserve the data on Robert Wone’s BlackBerry, and two e-mails he allegedly sent while he was at Swann Street were later erased. DC police purged their radio records of the night of the murder.

Heading into the trial, scheduled for May 10, Glenn Kirschner revealed under questioning from Leibovitz that the government was dropping its allegation of sexual assault.

“We will focus,” he said, “on tampering and obstruction of justice.”

There would be no murder charge.

In early March, Katherine Wone spent seven days in Rome with friends. It was her first vacation since her husband’s death. They arrived on a Wednesday.

On Saturday night, her friends went to see La Traviata. She had seen the opera a few times and decided to spend the evening alone.

“I let my emotions come to a head, and I had a good cry,” she says. “I allowed myself to think I should be enjoying this with Robert.”

If you see Kathy Wone at the courthouse, she will be surrounded by friends and family. Bill and Aimee Wone will be by her side.

“When a tragedy like this hits a family,” she says, “everyone needs to recalibrate. Initially, I wondered, ‘Where does this leave me?’ They made it abundantly clear I was still part of the family. If I’ve had an issue trying to figure out who I am now without Robert, they have been incredibly generous and patient.”

The Wones aren’t the only ones who have remained close. “All of Robert’s friends have more than stayed in touch,” she says. “We have very much become part of one another’s lives.”

They have consciously assumed Robert Wone’s role of remembering everyone’s special days; everyone stays in better touch.

Kathy is godmother to three of his friends’ children, “Aunt Kathy” to many others.

“We lost a great, great deal in losing Robert,” she says. “But I am also seeing more clearly how all the good in our lives, no matter how small or common—a pretty color, a reliable car, a chilled glass of wine—is evidence that good will always surface and beauty will always push through even in the darkest of times.”

At the Latin American Youth Center, not a week goes by that Mai Fernandez doesn’t reach for the phone to call Robert Wone. She’s facing a roadblock—she knows Robert can help her. Then she stops.

“Darn, I can’t call him,” she realizes. “Robert, where are you?”