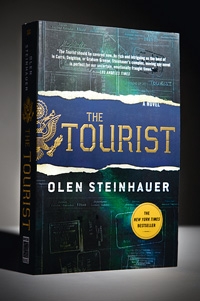

Washington has replaced London as the spy-fiction capital of the world.

For decades, British authors dominated, having invented the genre with such early classics as John Buchan’s The Thirty-Nine Steps, Eric Ambler’s A Coffin for Dimitrios, and Graham Greene’s This Gun for Hire. Starting in 1963 with The Spy Who Came in From the Cold, David Cornwell,a former British intelligence agent who wrote as John le Carré, established himself as the world’s best—and best-selling—spy novelist. Ian Fleming, Len Deighton, and Frederick Forsyth also did fine work.

But now American authors have come to the fore—and some of the most talented are Washingtonians.

Before World War II, the United States didn’t have many spy novels because we didn’t have many spies. That changed with military intelligence operations during World War II and the founding of the CIA in 1947. Soon we were knee-deep in espionage.

E. Howard Hunt, the longtime CIA agent who later became ensnared in Watergate, began publishing fast-paced tales in the 1940s, and Donald Hamilton’s popular series about Matt Helm, an assassin with a secret US agency, started in 1960. A turning point toward sophistication and quality came in 1973 when Charles McCarry published his first novel, The Miernik Dossier, and Robert Littell published his debut, The Defection of A.J. Lewinter.

McCarry served for ten years as a CIA undercover operative, and his Paul Christopher novels—particularly his 1974 masterpiece, The Tears of Autumn—combine an insider’s understanding of tradecraft with a stylistic elegance rarely seen in popular fiction. Unlike many novels that followed, McCarry’s books are pro-CIA: Paul Christopher is a patriot and a hero, a cloak-and-dagger Lancelot.

Littell’s early novels tended toward satire of the CIA, but in 2002 his long, ultra-realistic The Company fictionalized the CIA’s successes and failures during the Cold War.

Both writers offered their fictional versions of JFK’s assassination—McCarry’s The Tears of Autumn and Littell’s The Sisters—though they reached very different conclusions. The two men’s work drew on longtime Washington connections. McCarry lived here for years (he was once a writer for President Dwight D. Eisenhower and was editor at large for National Geographic), and Littell has been a frequent visitor, both as a Newsweek correspondent—he once interviewed Henry Kissinger in the White House basement—and later as a novelist researching the intelligence community.

McCarry and Littell paved the way for younger writers. James Grady, born in 1949 in Montana, had only a smattering of Washington experience when at age 24 he wrote a novel about the CIA. That 1974 book, Six Days of the Condor, reflecting the anger and cynicism of the Watergate era, became a popular movie, Three Days of the Condor, starring Robert Redford. Grady has long made Washington his home and has published many more accomplished thrillers, though none have soared as high as Condor.

In the 1990s, spy-fiction writers faced a new reality: The Soviet Union had collapsed, and the Cold War was over. In fictional terms, the Red Menace was kaput. Not to worry—Osama bin Laden and jihadist terrorism were surfacing, even before the September 11 attacks, and Middle East terrorists soon replaced Soviet spies as the bad guys.

“I remember when the Berlin Wall fell,” Jim Grady once told The Washingtonian. “I read three op-ed pieces in one week wondering who thriller writers were going to use as villains now. I don’t think the problem is finding the villains; it’s finding the heroes.”

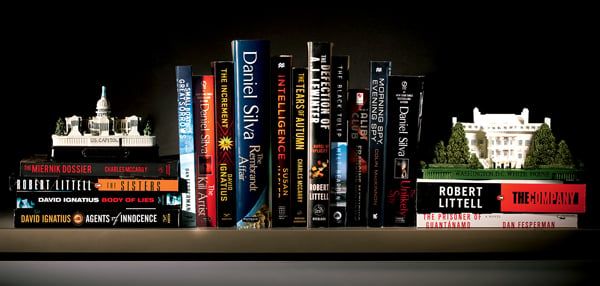

One of this decade’s most popular spy heroes was created by Daniel Silva, who grew up in California, studied journalism at Fresno State, and in 1984 went to work for UPI, but he always saw journalism as a steppingstone to fiction. On assignment in the Persian Gulf, he met NBC correspondent Jamie Gangel. They married, and Silva became a Washington-based writer and producer for CNN.

By 1994, he was writing An Unlikely Spy, about a British counterspy’s search for a German agent during World War II. The novel became a bestseller, and Silva followed it with two more about a CIA agent named Michael Osbourne.

Despite the success of the Osbourne novels, Silva wanted to develop a new character. One day, after reading two newspaper stories about Mossad, the Israeli intelligence agency, he was seized by the idea of writing about a retired agent who was called back to duty after a string of operational failures. That led to The Kill Artist (2000), which introduced Gabriel Allon, art restorer and undercover assassin.

Silva didn’t see that novel as the start of a series until he signed with a new publisher: “They said, ‘We want you to turn Gabriel Allon into a continuing character.’ I said, ‘You’re crazy.’ I didn’t think the world was ready for a Jewish superhero.”

The publisher was right—and a superhero was born. The Rembrandt Affair, the tenth of the increasingly popular Allon thrillers, appeared this summer and, like all the others, blends action, suspense, and an understanding of Middle East politics and history.

Silva lives in Northwest DC and says he can go for days without speaking to anyone except his wife and children—and he often must to maintain his book-a-year publishing schedule.

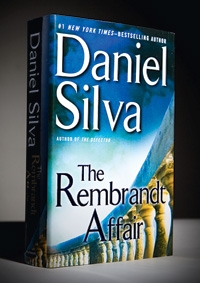

David Ignatius is a native Washingtonian. His father, Paul Ignatius, is the son of Armenian immigrants and was Secretary of the Navy during the Johnson administration as well as president of the Washington Post under Katharine Graham. Born in 1950, David Ignatius attended St. Albans, Harvard, and Cambridge before entering journalism. After ten years with the Wall Street Journal, several as a correspondent in the Middle East, he joined the Post and is now its foreign-affairs columnist.

Starting with Agents of Innocence in 1987, this globe-hopping journalist has written six excellent spy novels, most recently Body of Lies (2007) and The Increment (2009). Ignatius’s novels offer a subtlety, ambiguity, and psychological depth to rival John le Carré’s. They also reflect the concerns of a writer who has grown increasingly troubled by US involvement in the Middle East.

Ignatius once said that in his novels he struggles with the issue of the US government’s “seduction and abandonment.” He explained: “We encourage people to risk their lives for our vision of a better world, and then when the going gets tough, we leave them hanging. We did that at the Bay of Pigs, in Vietnam, in Lebanon in the early 1980s, in Nicaragua with the Contras—and now we are in the process of doing it again in Iraq. Basically, it’s immoral—this process of making promises that we as a nation are not prepared to keep.”

Ignatius’s moral concerns underlie his novelistic skill and do much to make his fiction outstanding. The Increment features an embittered CIA operative, Harry Pappas, who learns of a young Iranian scientist who wants to hand over information about his country’s efforts to build a nuclear weapon. It’s Harry’s job to prevent that weapon from becoming a reality, but he fears that hawks in the White House will try to use the unconfirmed report to launch a preemptive strike against Iran. These concerns are intensified because his only son volunteered for the Marines just after the 9/11 attacks and died in Iraq. Harry doesn’t want other young men to perish because of faulty intelligence or a rush to war.

“Harry’s anguish reflects my own anguish over the war,” says Ignatius, who initially supported the Iraq War but in time decided it was doing more harm than good.

Body of Lies was made into a film starring Leonardo DiCaprio and Russell Crowe. The author jokes that he never impressed his three daughters more than when he was able to introduce them to DiCaprio: “It was the only time they ever thought I was cool.” Ignatius lives in DC’s Cleveland Park with his wife.

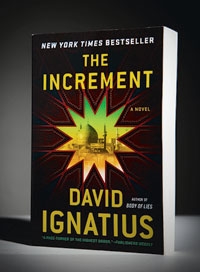

I wish we could claim Alan Furst (Night Soldiers, Spies of the Balkans, and others) as a Washingtonian, because he ranks with Ignatius at the pinnacle of today’s spy fiction. But he’s a New Yorker who’s mainly glimpsed here at signings. We can, however, claim ties to another top practitioner, Olen Steinhauer, who was born in Baltimore and raised near Richmond—and I’m told, visits here often to conduct interviews and check out the latest gadgetry at the International Spy Museum.

Steinhauer has lived in Europe in recent years, which helped inspire five novels that chronicled the Cold War in Eastern Europe—The Bridge of Sighs and The Confession are two of them. This series was followed in 2009 by The Tourist, the first novel in a trilogy about CIA agent Milo Weaver. In The Tourist, the CIA keeps highly skilled assassins—called Tourists—stationed around the world. When we first meet Weaver, he’s a burned-out Tourist who has quit the killing game but is lured back to save an old friend.

Part of the fun of reading novels about the CIA is the wildly different ways it’s portrayed. The Tourist is a portrait of the agency as a nest of highly lethal, surpassingly cynical vipers. It’s also a gripping story, and George Clooney’s production company has optioned the novel, with Clooney expected to star.

Many of today’s best American spy novelists have come out of journalism, but lately they’re rivaled by ex–CIA agents who have rejected the code of silence. Four books by such veterans—three of them former CIA agents, one a Middle East expert—are worth singling out.

When Milt Bearden retired from the CIA in 1994 after 30 years in its clandestine services, the agency showered him with honors befitting his status as a Cold Warrior who had directed the final years of its secret campaign against the Soviets in Afghanistan, then served as the agency’s station chief in Germany when Soviet forces withdrew from Berlin.

After retiring, Bearden published The Black Tulip, in which his hero, Alexander Fannin, works closely with real-life CIA director William Casey to expand US support for the Afghan warriors battling the Soviets. Early in the novel, Fannin provides Stinger missiles to the Afghans, and later he conspires with a KGB colonel to bring an end to the war. Bearden doesn’t gloss over backstabbing at the CIA, but he obviously believes in the agency and is proud of his record. If you want to know how the agency operated in Afghanistan, his fictional report is one of the most realistic accounts you’ll find.

Robert Baer attended Georgetown University’s School of Foreign Service, spent 20 years directing CIA agents in the Middle East, and since retiring has written three controversial books. His Middle East memoir, See No Evil, was the source for the movie Syriana, which won George Clooney an Academy Award.

In 2006, Baer published a freewheeling novel called Blow the House Down, which offers an alternative scenario to the 9/11 attacks in which Americans were involved in the planning. The story unfolds in early 2001 as agent Max Waller, who’s being forced out of the CIA for his independent ways, stumbles onto a conspiracy that no one else in government seems to care about. The novel is an in-depth look at Middle East politics, an angry portrait of the CIA, and a great read.

Colin MacKinnon’s Morning Spy, Evening Spy (2006) offers another alternative 9/11 plot. But while Baer was CIA, MacKinnon was editor of Middle East Executive Reports and Iran coordinator for Amnesty International. Still, he must have had friends in the agency, because his novel draws an entirely convincing portrait of a CIA agent, Paul Patterson, operating both in Langley and the Middle East, where his search for Osama bin Laden leads him toward the upcoming 9/11 attacks.

MacKinnon’s novel is less flamboyant than Baer’s, but he’s angry, too, and the book doesn’t hide his belief that the FBI and CIA could have prevented the attacks if they’d done their jobs better.

MacKinnon, like Baer, offers frequent glimpses of Washington in his novel, with scenes at Clyde’s, the Dubliner, and other well-known bars and hotels. His protagonist lives in Arlington, and one morning at dawn he walks across the Chain Bridge:

“At this hour traffic over the bridge is still sparse. As the vehicles pass, one by one, their weight makes the structure flex and bounce under my feet, its movement giving me an eerie, unsteady feeling.” Not unlike, perhaps, the feeling an agent knows when he’s entering dangerous territory.

After many years abroad, MacKinnon now lives in Chevy Chase.

All of the writers mentioned so far are men, but a number of women are staking a claim as spy novelists.

Francine Mathews grew up in Washington, attended Georgetown Visitation and Princeton, and became a CIA analyst at age 26. She spent four years with the agency and says she loved her work but left in 1993 to write fiction. She has published four well-crafted spy novels, including The Alibi Club and The Cutout, but has devoted more time to her ten Jane Austen mysteries.

Susan Hasler worked for the CIA for 21 years, much of that time as a speechwriter and counterterrorism analyst. She retired in frustration in 2004 and this year published a blistering—and delightful—satire of the agency called Intelligence. Her book makes clear she feels that the Bush White House ignored evidence provided by analysts such as her that Saddam Hussein was neither complicit in the 9/11 attacks nor possessed of weapons of mass destruction and that the United States invaded the wrong country.

As the plot unfolds, Maddie James and her fellow analysts fear that a second major attack—intended to kill thousands in Washington—is coming and they’re scrambling to prevent it without much support from higher-ups. At one point, Maddie rails against her bosses: “What do these people have for brains? ‘Intelligence community?’ What intelligence? I tell them something’s going to blow up and they look at me like I’m hallucinating.”

Hasler lived in Reston during her CIA years and now lives in tiny Singers Glen in Virginia’s Rockingham County, where life is almost certainly more serene than at Langley. She says her novel was inspired by satires such as Dr. Strangelove and Catch-22, that the CIA’s Publications Review Board didn’t change a word of her manuscript, and that she has written a new novel with some of the same characters.

Other writers could be mentioned, including Barry Eisler, whose series about John Rain, a professional assassin, draws on his three years with the CIA. Former Washington Post movie critic Stephen Hunter’s peerless sniper, Bob Lee Swagger, sometimes clashes with intelligence agencies, but Hunter’s are not really spy novels. Baltimore Sun foreign correspondent Dan Fesperman has written seven very good spy novels, including The Small Boat of Great Sorrows and The Prisoner of Guantánamo.

What’s the bottom line in this outpouring of spy tales?

First, a high-minded one: The CIA is a powerful, mysterious agency that has done much good but has also dabbled in secret wars, assassinations, and other dark deeds. It behooves Washingtonians to know what the country’s spies are up to, and good spy fiction can, along with aggressive journalism and congressional oversight, inform us and be a check on the agency’s excesses. These novels offer different portraits of the agency but, taken together, probably add up to something like the truth.

In more selfish terms, it’s a delight for lovers of fiction to have this profusion of excellent spy novels appearing, and to have so many of them set in the city we know best.

This article first appeared in the November 2010 issue of The Washingtonian.