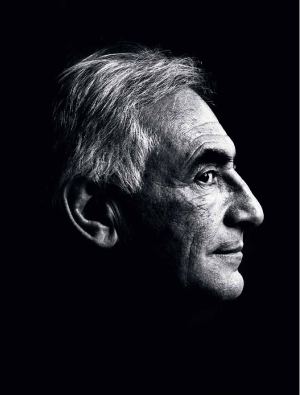

Editor’s note: The June issue of The Washingtonian—which has already been printed and is currently being mailed to subscribers and delivered to newsstands—includes a profile of IMF chief Dominique Strauss-Kahn, who has lived in relative obscurity in Washington for the last three and a half years. Titled “The Invisible Man” and written by French journalist Apolline de Malherbe, the profile was meant to introduce Strauss-Kahn’s neighbors here in Washington to a man considered one of Europe’s leading politicians—a man, as we say in the article, who might well be standing next to you in line at Whole Foods. We had no way to know that Strauss-Kahn would be front-page news by the time the issue arrived in the homes of subscribers and on newsstands; this weekend news broke that Strauss-Kahn had been arrested for allegedly sexually assaulting a hotel maid in New York. What follows is an updated version of the article:

When Dominique Strauss-Kahn was taken into police custody on Saturday afternoon for an alleged sexual assault, it marked the likely end of what had been a remarkable political comeback. “DSK,” as he’s known throughout France, had gone in just a few years from an outsider in French politics, the loser of the Socialist Party’s presidential primaries, to the man many had come to see as their country’s savior.

As head of the IMF, he lived in Washington for the last three and a half years, one of those very powerful men who float through the city without attracting much notice. He was the leading candidate to become the next president of France, yet Strauss-Kahn and his wife could sit on the patio at Cafe Milano without a single paparazzo or gawker. And while the two of them were expected to unseat one of the most famous couples in the world—Nicolas Sarkozy and Carla Bruni—they didn’t get a second glance in the checkout line at the Georgetown Whole Foods.

On the other side of the Atlantic, it was another story. Recent polls predicted that Strauss-Kahn would have knocked off Sarkozy with a 61-to-39-percent win. The country’s future seemed to hinge on the question of whether he would run. Politicians and journalists had taken to beginning their sentences with “If DSK comes back . . . .”

Then, on Saturday afternoon, he was apprehended just minutes before his Air France flight to Paris was scheduled to take off from New York’s Kennedy International Airport. The news that he was accused of attacking a maid at the New York Sofitel, where he was staying, caused what has been described as a “political earthquake” in France, shaking the country’s political landscape.

The IMF seemed to quickly cut ties with Strauss-Kahn, announcing within hours of his arrest that first deputy managing director John Lipsky would take the helm of the fund as acting managing director. In France, Strauss-Kahn’s political allies have spoken out in his defense, and even his rivals have been cautious in their statements, perhaps not wanting to seem too gleeful about the news.

Strauss-Kahn was expected to plead not guilty this morning, and his wife, Anne Sinclair, has said she's certain he's innocent. In France, the widespread disbelief that this man who was seen by many as a champion of their country—and who was so close to becoming president—would do such a thing has given rise to serious talk that he was framed in a plot to discredit his political career, the Socialist party, or the IMF. UPDATE 1:30 PM: Dominique Strauss-Kahn appeared in court this morning and pleaded not guilty to attempted rape and other charges associated with an alleged sexual attack. The judge ordered that he be held without bail. If convicted, he would face up to 25 years in prison. In the meantime, new allegations arose that he had sexually assaulted another woman in 2002.

Strauss-Kahn has long been seen as a political survivor. He has weathered other storms—including an affair with a subordinate in 2008 that nearly cost him his job at the IMF. But while few French political analysts have been ready to say with certainty that his political career is over, the consensus is that it will be very difficult for him to recover.

In order to enter the Socialist primary for the May 2012 presidential elections, Strauss-Kahn would need to declare his candidacy between June 28th and July 13th. It’s too soon to say what all of the implications of Strauss-Kahn’s arrest will be—some fear it will push French politics to the far right; others worry that Strauss-Kahn will leave the IMF rudderless at a critical time. But for now one thing seems clear: Though he seemed poised to become the next French president, his campaign is probably over before it even began.

To understand Strauss-Kahn’s trajectory, rewind to November 16, 2006: Ségolène Royal was chosen by the Socialists to become the party’s first female candidate for president. She got 60 percent of the vote; Strauss-Kahn trailed with 20 percent.

It was a humiliating defeat: Strauss-Kahn was an acclaimed finance minister, a successful mayor of Sarcelles, a sizeable and hard-to-manage suburb just outside Paris’s beltway. He was a well-regarded politician, an insider who got the support of key political bigwigs, including Lionel Jospin, the French prime minister from 1997 to 2002. Ségolène, as she’s called, was a novice. DSK’s team couldn’t believe she had managed to portray herself as the “people’s candidate,” the outsider who would shake up the party.

After losing the bitter primary, Strauss-Kahn’s camp did little to help Ségolène against Sarkozy. DSK needed a new lease on life, a new platform. The story goes that he and his advisers started taking a close look at all the big international institutions where he could burnish his image. Then, in June 2007, the International Monetary Fund’s managing director, Rodrigo de Rato of Spain, announced that he wanted to step down. By tradition, the head of the World Bank is an American and the IMF head is a European, so news of the opening rocketed around the capitals of Western Europe.

Strauss-Kahn, then 58, had the political skills and experience to be a serious contender. He boasted a PhD in economics, had been a professor of economics at the prestigious Sciences Po—as the Paris Institute for Political Studies is known—and was a visiting professor at Stanford. He had also earned a lot of respect, both at home and abroad, as France’s finance minister in the late 1990s.

Jean-Claude Juncker, a close friend and president of the Eurogroup—composed of finance ministers from countries that use the euro as their currency—endorsed DSK as the European Union’s candidate to head the IMF. But before making it public, DSK had to win Sarkozy’s support. It wasn’t that hard.

The French president had two good reasons to send Strauss-Kahn to the IMF. Sarkozy saw having a Frenchman at the head of the powerful international organization as a way to elevate the country’s leadership on the world stage. It was also a chance to get rid of a potential rival. The IMF job was a five-year stint, renewable once. It began in the fall of 2007 and would end in late 2012—long enough to keep Strauss-Kahn away until after the May 2012 presidential elections. (That strategy might be familiar to Barack Obama, who sent Utah’s GOP governor Jon Huntsman, a potential 2012 rival, to be ambassador to China. Huntsman resigned in January to return to the United States and explore a run for the Republican 2012 presidential nomination.)

After getting Sarkozy’s blessing, DSK began a world tour to win the support of members of the IMF board: the United States, Europe, China, Japan. Everywhere he went, he convinced the members to back him, and he promised not to quit before the end of his term—he even implied he would stay for a second term. In the end, the only member he didn’t get onboard was Russia, which had its own candidate.

On November 1, 2007, Strauss-Kahn got the IMF job. He now had 2,900 people from 187 countries working for him and a budget of $340 billion, with $600 billion out in loans. He traveled 150 days a year across the globe. Heads of state called him on his BlackBerry.

“I have the opportunity to tell every head of state or head of government on the planet what works and what doesn’t,” he said on French TV in February. His mission? “Foster global growth and economic stability, provide policy advice and financing to countries in economic difficulties, and reduce poverty in the world.”

When he arrived, the IMF—created in 1944 during the Bretton Woods conference in New Hampshire—had lost much of its credibility. It was decried by poor nations as a bully giving with one hand, strangling with the other. The conditions it imposed before awarding a loan were so drastic that many economists said it was no longer fostering growth. And despite its traditional European leadership, the IMF was seen as a tool of the US Treasury.

As DSK took charge, critics raised questions about the IMF’s usefulness. It had been created in the wake of the Depression and World War II. Now, at the dawn of the 21st century, when all the major economies felt invincible, what was the point of keeping alive such an enormous and expensive machine? No one was losing sleep over the threat of another global financial crisis.

Strauss-Kahn began by getting rid of 400 people, 15 percent of the workforce, through buyouts. It was a very traditional social-democrat approach—nobody was fired, only strongly encouraged to leave with generous subsidies and help. But cutting 400 jobs during his first months in office didn’t make him many friends.

He reorganized the IMF’s shares—which determine how much control each country has over the Fund—to boost the role of emerging economies. In November 2010, China became the third-most powerful country on the board, after the United States and Japan. “This historic agreement is the most fundamental governance overhaul in the Fund’s 65-year history and the biggest-ever shift of influence in favor of emerging markets and developing countries to recognize their growing role in the global economy,” DSK said in November 2010.

This movement toward a more balanced distribution of power may lead to another revolution: breaking with the tradition of having a European IMF chief. The next managing director of the IMF could come from either Latin America or China. To pave the way, DSK appointed Zhu Min, former deputy governor of the People’s Bank of China, as his special adviser. It’s the highest position a Chinese person has held at the IMF.

But the biggest force driving the IMF revolution was the 2008 financial meltdown, the largest systemic risk to the global financial system since the Great Depression, which had helped spawn the IMF nearly 70 years earlier.

“Before the crisis there was this idea—do we need an institution like the IMF?” DSK told Time in July 2010. “It was like wondering about the need for firefighters when you don’t have a fire.” DSK likes to think that when the fire did come, he was the one who played the role of fire chief—a role that Sarkozy and Obama also would claim.

At the G20 summit in London in April 2009, the IMF countr

y members committed to tripling the loan capacity of the Fund, from $250 billion to $750 billion. It showed that the IMF could be a vital tool in the crisis.

The G20 met again in Pittsburgh in the fall. At the official opening dinner on September 24, Strauss-Kahn sat across from President Obama. United Nations secretary general Ban Ki-moon was to DSK’s right. The Frenchman looked as if he were presiding over the dinner on an equal footing with the President of the United States. As a chess player—some say he plays up to two or three hours a day on his iPad—Strauss-Kahn understood the value of having a key role on the world’s chess board.

The Greek debt crisis in May 2010 was a turning point for the IMF. For the first time in its history, the Fund lent money to a country in the European Union: 30 billion euros, its biggest loan ever. The IMF had regained its relevance.

During all this, Strauss-Kahn was discovering his new home of Washington with his wife, Anne Sinclair, at his side. It was a change in more than language alone.

In France, Sinclair can’t navigate the Parisian upmarket department store Le Bon Marché without being constantly stopped. Sinclair is France’s Katie Couric and the country’s most famous TV journalist of the last 30 years.

From 1984 to 1997, she hosted the weekly TV show 7/7 on the TF1 network. In a country of 62 million, 10 million to 12 million watched her each Sunday evening at 7. By comparison, 60 Minutes draws 13.2 million viewers weekly in a country of 300 million. The CBS Evening News—which Couric is leaving in June—draws 5.5 million nightly viewers.

Sinclair’s show was a one-on-one interview, often compared to Larry King Live or Charlie Rose. She hosted Bill Clinton when he was President, Hillary Clinton when she was First Lady, Shimon Peres, and Mikhail Gorbachev, among others. Most French viewers could identify Sinclair’s voice with their eyes shut. She was a tough interviewer who wouldn’t let go of her guests. A brunette, she has eyes that are an almost electric light blue.

When DSK became France’s finance minister, Sinclair left the TV spotlight to host a radio show. And when he became head of the IMF, she quit journalism to come with him to Washington.

Strauss-Kahn is her second husband, she his third wife. She liked to join him on his travels: Panama City, Singapore, Kiev, Yalta, Algiers, South Africa. She had her own schedule and meetings, and she took pictures and posted them on her personal blog, Deux ou Trois Choses Vues d’Amérique—French for “Two or three things seen from America.” She wrote about politics, American institutions, and Barack Obama as well as Snowmageddon, Halloween decorations in Georgetown, and visiting the White House gardens. She sometimes uses the blog to post critical comments about Sarkozy’s politics.

“Anonymity is a refreshing luxury,” DSK told the French magazine Paris Match a few years after moving here. For Sinclair, the move was a homecoming.

She was born in New York City in July 1948. Her grandfather, the art dealer Paul Rosenberg, had moved to the States from France to escape Nazi occupation. He opened a gallery on the Upper East Side where he organized shows of Picasso, Renoir, Braque, Matisse. Rosenberg’s wife was painted by Picasso with Sinclair’s mother as a baby on her lap. Sinclair is a member of the Picasso Museum’s board in Paris.

She and her husband bought a $4-million house in Georgetown next to Rock Creek Park. DSK’s political friends have said Sinclair bought the house—being seen as wealthy isn’t good politics in France, especially for a Socialist. But he probably could have afforded it on his own. He earns $500,000 a year at the IMF and doesn’t have to pay income tax.

Strauss-Kahn has four children from his previous marriages and Sinclair has two, plus grandchildren. In Washington, they settled as a tribe: DSK’s brother, Marc-Olivier Strauss-Kahn, was appointed visiting senior adviser at the Federal Reserve board and administrator of the Inter-American Development Bank. Marc-Olivier was sent here by the Central Bank of France; his wife works at the World Bank. Sinclair’s younger son, David Levai, also made his way here and got a job as a program manager with a microfinance institution. “He often comes to see us by bike,” Sinclair told Paris Match.

The family liked to gather on Strauss-Kahn and Sinclair’s large patio, where they embraced the American barbecue tradition. When they didn’t want to cook, they ordered in from Cafe Milano or went out. Cafe Milano was DSK’s den, mainly for weekday lunches. He also liked a good steak at Morton’s and the French cuisine at Bistrot Lepic and Bistro Français.

Georgetown’s village atmosphere was a big change for the couple. In Paris, they have a gorgeous apartment on the historic Place des Vosges in the trendy Marais neighborhood. “Georgetown is close to everything, I walk a lot, it is a very pleasant life,” Sinclair told Le Figaro. DSK added: “I had this vision of a very provincial town. But on the contrary, there is a very rich cultural life here, we meet people coming from the whole world. And I appreciate being ten minutes away from nature, which is totally new to me.” They sometimes escaped to the Chesapeake Bay or Shenandoah National Park.

Before moving here, Strauss-Kahn and Sinclair had already seen life in DC by watching The West Wing. “Anne and I both adore this TV show!” DSK told Paris Match. The series gave them clues to the rules of political life inside the Beltway.

But DSK didn’t take one thing into account when he moved here: When it comes to fidelity in marriage, the standards in the United States are higher than in France.

On October 18, 2008, the Wall Street Journal splashed a story on its front page: “The International Monetary Fund has launched an investigation into whether its chief, Dominique Strauss-Kahn, abused his position in connection with a sexual relationship with a subordinate, in a case that could roil a key global institution at a crucial moment in the world financial crisis.”

The news flew across the Atlantic—on television, on blogs, everywhere. Back home, Strauss-Kahn had been known as a ladies’ man. But it was just whispered, never printed. A front-page article in the Wall Street Journal —what a humiliation!

The subordinate in question was Piroska Nagy, a Hungarian-born senior economist who was the head of the IMF’s Africa section. She was also married. They both claimed it was only a one-night stand in Davos during the World Economic Forum. There was an investigation, and on October 25 the IMF board concluded that the affair was “regrettable and reflected a serious error of judgment on the part of the Managing Director.” But DSK was cleared of harassment and abuse of power.

Strauss-Kahn presented his apology publicly, to his wife, his family, and his staff at the IMF. It may be a classic scene of American politics—a contrite husband, his betrayed wife by his side—but it wasn’t something a French politician had ever had to do before.

Strauss-Kahn wasn’t alone in his mixing of extracurricular activities with international business in Washington. A year before DSK’s scandal, his predecessor, the Spaniard Rodrigo de Rato, stepped down because of an affair. According to people who know the case, de Rato separated from his wife during his time in Washington and was having a relationship with a woman who couldn’t get a visa to the United States. Unable to bear the separation, he left Washington. Not long before, Paul Wolfowitz was forced to resign from the World Bank’s presidency after allegations that he had abused his power to boost the salary of Shaha Riza, his girlfriend.

But together with his wife, Strauss-Kahn weathered the storm. Sinclair posted on her blog that she and her husband “were in love like on a first date.”

Sarkozy lectured DSK the next time he saw him, not only about his behavior but also about the timing. In the middle of the worst crisis in decades, didn’t he have better things to do than have a love affair with a subordinate? And what about the French reputation? Some would be only too happy to point out that his behavior was oh-so-French.

In the United States, DSK’s affair might have ruined his political career. But after France’s initial surprise at his public humiliation, the “Piroska scandal” had no impact in the polls. The pictures of him in the company of Obama and other world leaders helped establish his image as a ready-to-lead president. And his experience in addressing the financial crisis was one of his trump cards.

As head of the IMF, DSK is not allowed to say a word about French politics. “I am the managing director of the IMF, and I am only that,” he has said to evade questions from the French media. (Strauss-Kahn and Sinclair declined interview requests for this article, as they have for almost all media inquiries this spring.)

Prior to his arrest, DSK claimed he had made up his mind about whether to run but wouldn’t let anyone know what he was thinking. The only clue came in March, when Sinclair dropped a bomb by telling the magazine Le Point: “I read in various French p

apers that Dominique’s reelection as managing director of the IMF was a sure thing. As far as I’m concerned, I don’t wish to see him serve a second term.”

Throughout France, Sinclair’s statement was seen as “the sign”—that DSK would come back, that he would run for president.

Now, however, all questions about his political aspirations—at least in the near term—have taken a back seat to discussions of guilt or innocence.

Apolline de Malherbe moved from Paris to Georgetown one year after DSK did. She is Washington correspondent for BFMTV, the number-one news channel in France.

Subscribe to Washingtonian

Follow Washingtonian on Twitter

More>> Capital Comment Blog | News & Politics | Party Photos