The official diagnosis came at the tail end of winter break. The spring semester hadn’t started yet at the university in DC where he was completing his three-year term as chair of the Literature Department—a bureaucratic burden he couldn’t wait to get out from under—and he was still tan from the week he and his wife had spent in Key West.

It was 1995. He was 51; Amy, his wife of 22 years, was 45. He would look at Amy’s glowing face, the face he’d fallen in love with when she’d walked into his classroom on the first morning of the first class he’d ever taught at the university—that lovely face with its high cheekbones and the endearing gap between her front teeth—and wonder how he could ever have been so lucky. Because they had no children, they gave their attention to each other, and life, they felt even in their secret hearts, was good.

It was embarrassing how little they really knew about the disease. At the time of his diagnosis, they knew only that it was neurological and that, although not necessarily fatal, it was incurable and progressive. He had always associated it with a tremor of the hand or the head, but the fact that he displayed no tremor proved nothing because the symptoms could vary markedly from one person to another.

They had learned you couldn’t detect it with a CT scan or an EEG or MRI. Which is why he’d been given the little pink pills. The diagnostic logic of the little pink pills was unassailable: If they relieved the stiffness he had been feeling in his right arm and allowed him to write legibly in longhand, it could only mean that what the pills were providing—a substance called dopamine—must be the thing he was deficient in.

So he’d taken the pills with them to Key West, along with a carefully drawn-up schedule that involved increasing the dosage day by day and then decreasing it after maintaining the full dosage for three days. It was up to him to monitor how he felt, whether his right arm swung easily as they strolled down Duval Street or whether it continued to hang stiffly by his side, and whether he was able to write a legible postcard or jot down a phone message so Amy could read it.

Dopamine, it turned out, was what allowed nerve cells to communicate with one another. A lack of dopamine meant that cells in your brain that should have been producing it no longer were; in fact, they were dying out, and they were apparently irreplaceable.

The result was what the doctors referred to as a “movement disorder”—he’d been told that at its most advanced stage you simply froze up. On the other hand, this method of diagnosis was in itself evidence that the symptoms could be ameliorated with pills. So as the last doctor—the one who had made the diagnosis—rather hopefully pointed out, it was really a good-news/bad-news situation. Of course, the doctor had to admit that the good news was compromised by the fact that over time the little pink pills gradually lost their efficacy.

But ultimately the news was bad for everyone, wasn’t it? At some point the efficacy of everything wore out. And, thinking that, he took a certain satisfaction in the fact that everyone’s span of years was equally finite, if not of equal length.

During that week in Key West, they had hardly known which outcome to root for. Surely it would be better if the pills didn’t work, because that would mean that at least he didn’t have Parkinson’s disease, but then again, Parkinson’s could be better than whatever else it might turn out to be, and at least then they’d know for sure what it was. Because in a way, they told each other, the worst thing was not knowing. They knew better now.

In the 15 years since he’d been diagnosed, the disease had progressed to the point that without the pills he couldn’t walk. The only time he was without them was in the middle of the night—then he could barely move his feet to go to the bathroom. He’d have to more or less drag himself along by holding onto the wooden rails they’d had installed along the hallway. He’d recently begun to keep a plastic urinal next to the bed to avoid having to make the trip to the bathroom. Even when he was medicated, doorways and thresholds presented a risk that more than gave him pause.

Festination, they called it—the clinical term for the way you could freeze up, your legs trembling, your feet taking little stuttering steps, as you tried to negotiate a passageway or cross a threshold. His body’s momentum would continue to carry him forward while his legs shook and his feet stayed put. Then, if there was nothing for him to grab onto, he would fall down—usually on an already banged-up knee—and have to hold a bag of ice against the knee for 15 minutes every half hour for the next several hours if he expected to be able to jog the next morning on the treadmill at the gym.

His neurologist had prescribed a daily dose of aerobic exercise because she said research showed that exercise helped ease the symptoms and possibly slowed down the disease’s progression—as well as doing a lot of other good things. She was sure he’d been doing as well as he’d been doing because of his regular exercise. And he’d come to feel he couldn’t do without the gym—it had become the only time he felt at one with his body.

So six days a week he did a 50-minute workout that combined a stationary bicycle with an elliptical machine and a treadmill. He’d watch himself in the mirrors and admire the fluidity of his movements. He liked looking at himself, especially if he was on the treadmill directly under the long fluorescent light that made his hair look shiny and thick. People told him he didn’t look anything like his age. Although there was a little gray in his mustache and beard, for some reason the hair on his head refused either to fall out or turn gray. He looked about 20 years younger than he was, like a man in the prime of life.

He owed his time at the gym to the pills. Without them, he’d have had to use a walker or wheelchair. But the pills were complicated. Although he had started out needing to take only a couple a day, by 2010 he was taking two to three every 2½ hours, and they were to be taken not less than an hour after a meal nor less than half an hour before a meal, especially if he was eating protein. This could be bypassed to some extent with a form of the drug that dissolved under his tongue and that was faster-acting but also seemed to wear off more quickly.

The timing of this schedule was dictated each day by exactly when he took the first dose. Before he could safely make his way from the bed to the bathroom and from there to his study, he had to lie in bed and wait at least 30 tick-tocking minutes while the first dose of dopamine passed from the saliva under his tongue to his bloodstream to his brain so that his neurons could once again relay his wishes to his legs and he could walk—even though, lying there in bed, he could move his legs without any problem. This complicated regimen, along with the amphetamine-like side effect of the drugs, gradually but radically altered not only his sleeping habits but the whole diurnal rhythm, the entire pattern, of his daily life.

His current procedure was to take his first dose at 3:30 am and rise at 4, being careful not to wake Amy. A few years back, he’d developed a daily routine, which had lasted more than a year, of making pancakes for himself after he got up. He made them every day because he was a creature of habit given to rote repetition, something he was grateful for now because it was necessary to repeat his pill regimen methodically day after day. He’d take his second dose at 6, just before going back to bed for another two hours. As a former night owl, he found it hard to believe he was going to bed these days at 9 pm—and that he was now an early riser.

Next: When the disease takes over language

Despite everything, he wasn’t depressed. In fact, he was remarkably cheerful as well as more outgoing and sociable than ever before. This ebullience was part of a personality change that he seemed to have undergone and that had culminated in his last year of teaching. A speeded-up, hyper-emotional, extroverted version of himself had emerged, and this surprising sociability was one aspect of it.

In retrospect, it seemed clear that his personality change was a side effect of an excess of the dopamine pills. But the change had emerged so incrementally that he couldn’t say exactly when it had started. In the past he had always seemed, at least to himself, introverted and self-conscious to the point of shyness. Now he was given to starting conversations with strangers—for instance, a woman with whom he stood looking at the titles in a bookstore window and to whom he began explaining the difficulties he was having finding a publisher for his novel. Or the saleswoman from whom he’d bought a Greek fisherman’s cap and a little snap-brim Frank Sinatra “Come Fly With Me” number, both of which would come in handy, he explained to her, when he went into the hospital for brain surgery, for which they’d have to shave his head—the saleswoman standing there, seemingly frozen in place by the intensity of his explanation and by the way he punctuated it with a series of rapid gestures that kept his body in constant motion.

He had begun taking more of the medicine than his regimen specifically called for because he believed he had to when he was teaching if he was going to avoid becoming symptomatic in the classroom, but the truth was that he also liked the energy the pills gave him. He was almost always keyed up. And his emotions had risen so close to the surface that the slightest bump of sentiment could make them spill over.

In his class, he could become so moved reading aloud a passage from Tender Is the Night or discussing the final chapters of Toni Morrison’s Song of Solomon that he would get choked up and have to stop. But he also frequently felt he possessed the strength and energy of Superman, and at night, caught up in his vivid dreams, he often had a sense of possessing some magical power, the specifics of which he could never quite identify.

More problematic than the change in his sleeping habits was the fact that the energized but somewhat unfocused intensity he felt when his meds were “on” also came into play when he was driving. He would turn the car stereo up and bang out the rhythm of “Running on Empty” or “Can’t Buy Me Love” on the dashboard as he drove to or from school.

One night, driving along Connecticut Avenue looking for an Irish bar where his students had invited him to join them after a fiction workshop and trying to turn around after failing to find it, he crashed his Honda Accord into a four-foot-high guard pillar at the corner of a building because he thought the car was in reverse when it was in drive. No one had been injured, but Amy convinced him to stop driving to school and began taking him to and from the Metro.

Some weeks later, when he was running to catch the shuttle bus to school after getting off the Metro, he tripped and went flying through the air as if he really were Superman. He landed spread-eagled on the pavement but got away with only a cut on his hand.

He’d been teaching at the university for 37 years, but it was because he had Parkinson’s disease that he decided to take early retirement. Besides his movement disorder, his voice, which had always been strong and expressive, had become much softer and more of a monotone. To be heard in a large class, he had to use a microphone.

Then there was the manic quality that had come to characterize his behavior—he couldn’t see himself sustaining such a level of intensity year after year. He was beginning to feel a little inarticulate sometimes, usually when the meds were really on, as though the vocalization of his thoughts had fallen a little out of sync with his impulse to speak, so his usual verbal facility felt impaired.

The fact that the disease could affect his ability to use language was so disconcerting that he couldn't believe it.

The fact that the disease could affect his ability to use language was so disconcerting that he couldn’t believe it—surely it was just a temporary side effect of the meds. He was heartened by the fact that, so far, he’d experienced no dimming of his ability to compose sentences, and he couldn’t help believing that, although the Parkinson’s might affect his motor skills, it wouldn’t really affect his mind. After all, he’d written his novel well after he’d been diagnosed with Parkinson’s, most of it within the past five years. Still, retirement from teaching had seemed like a good idea—and then he’d be able to write full-time, he’d told himself, like taking an extended sabbatical.

By the last semester before his retirement, he was taking so much medicine that, as a last resort, his neurologist in Washington had recommended Deep Brain Stimulation. DBS involved inserting electrodes into sectors of his brain where electrical stimulation could be administered by a pacemaker-like device, which would be implanted under the skin of his chest beneath his collarbone.

Although the success of the procedure was not guaranteed, the electrodes had a chance of relieving his symptoms more effectively than the pink pills could. As radical as that sounded, and although he was concerned about the cosmetic aspect of the device, he’d been sold on the idea—so much so that he had eagerly submitted to a battery of cognitive, physical, and psychological tests to ensure that he was capable of managing the stress of brain surgery. After he retired and he and Amy had moved to Cape Cod, they had located a team of neurologists in Massachusetts who were set to follow through with the surgery.

DBS seemed most successful in treating patients with tremor because the effect on the tremor could be gauged while the electrodes were being positioned. Walking, on the other hand, couldn’t be observed on the operating table, so without a tremor to monitor, the procedure would be more hit-or-miss.

His neurologist wanted to observe him when he was free of medication for 48 hours, because she believed it likely that a tremor was being masked by the drugs. But when he was drug-free and still exhibited no tremor, it seemed clear that in his case DBS didn’t hold the same promise it did for patients with tremor. And although without the pills he had difficulty walking, he had been able to get around with the help of a wheelchair and a cane—evidence in itself that there were less invasive ways of dealing with his symptoms than brain surgery. So, after further consultation with his doctor, with a feeling of relief, he and Amy decided to postpone the DBS.

Following this decision, his neurologist made adjustments to his medication regimen, and soon his bright new personality began to recede and his behavior gradually became, at least to the casual observer, more normalized. The doctor told him to stick to his drug regimen without taking any extra doses to deal with the symptoms that might occur in the “seams” between the “on” times of his medication. She also prescribed a drug that had originally been designed to prevent flu but that recently was found to reduce the spasmodic body movement, or dyskinesia, that was a side eff

ect of the dopamine drug.

The trick was to find the right balance: enough of the drug to allay the symptoms but not enough to make him dyskinetic and overwrought. The result of these changes was gradually to return his familiar personality to him, which he thought of as a mixed blessing, because he’d come to enjoy his new social fearlessness.

Next: The accidental falls continue

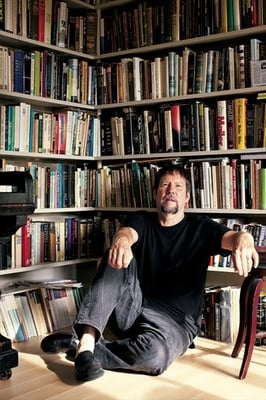

Kermit Moyer and his wife, Amy. He calls her “the linchpin that kept life on track.”

In the meantime, the accidental falls continued. The worst had occurred in February as he was carrying in a pizza he’d picked up for dinner. He’d had a good workout at the gym. He was feeling fit and looking forward to a pre-dinner martini with Amy. It was late afternoon, the time of day he loved most because of the way the Cape Cod sun would shine in from the other side of the pond at a nearly horizontal angle, like the light in an Edward Hopper painting. Coming in that afternoon from the garage to the kitchen, he was holding the flat, warm pizza box when, as he crossed the threshold, his legs started shaking and he took a rapid succession of tiny stutter steps, as if dancing in place, increasing his forward momentum even as his legs refused to take another step, so that he didn’t so much fall as launch himself forward, still holding the box level as he went flying headlong toward a closed closet door with a metal lever doorknob about four feet in front of him.

His right shoulder went crashing into it, and even as he landed on the floor in a twisted posture, he knew something had happened. The pain in his shoulder was unprecedented. He thought he must have broken the shoulder, but he learned later that he’d dislocated it.

Shortly after the accident, his friend Jim—who had overseen the renovation of their Cape house—believing that he wouldn’t have fallen if he’d had something solid to grab onto, went down to the border of the pond and cut branches of a tough scrub tree into a number of two-foot sections. Jim stripped the bark off, sanded and dried them in the oven, and bolted them to the wall at strategic points inside and outside the house. Jim was also an artist, and these grab bars were like pieces of sculpture and also, in their resemblance to bones, like memento mori.

It was a loving gesture, but it couldn’t prevent him from breaking his big toe three months later when he spasmodically kicked the frame of the bathroom door or, a couple of months after that, falling on the hardwood floor of their living room and dislocating a knuckle in his right hand. It was getting so that triweekly physical-therapy sessions were becoming his normal routine. It struck him that what was likely to get him in the end wouldn’t be the Parkinson’s per se; it would be a fall caused by it—a fall that, even if it didn’t do him in, would deprive him of his lifeline by keeping him away from the gym.

After each fall, it was Amy who wrapped an ice pack around the injured knee or finger or toe and drove him to the hospital. It was Amy who looked after him, planned their meals according to his medication schedule, reminded him when it was time to take his pills, encouraged him with her own easy and uncomplaining adaptation to his changing daily rhythms, kept track of his doctor’s appointments, and alerted him to those moments when his extroversion threatened to become overbearing or when his interior drama seemed to absorb him to the exclusion of everyone else.

If she had always been a strong organizing force in their life together, now she had become the linchpin that kept that life on track. She made it possible for him to be as self-involved as Narcissus and yet as connected to another person as perhaps only someone happily married can be. He was constantly buoyed up by her belief in their extraordinary good luck, a symbol of which was the way, from any window of their house, they could see the pond, ever-changing as it reflected the sky and the foliage of the woods as well as playing host to flocks of migratory ducks, swans, geese, and herons that visited it according to their seasons.

If you were lucky enough, living with a chronic disease meant you had to accept such loving care and assistance without imagining, on the one hand, that everything revolved around you and, on the other, losing your sense of autonomy. That turned out to be the real challenge. Could you receive love and be grateful without expecting to be waited on, and could you depend on others and yet avoid becoming dependent? At stake was nothing less than your sense of identity.

In February 2010, one year to the day after he dislocated his shoulder, his novel was published, and he found himself in the public eye—interviews on TV and radio, a profile in a local paper, book readings and signings—and was forced to confront the question of his identity in a public arena. For the last 15 years, he’d kept his disease closeted: His practice had been to say nothing about the Parkinson’s publicly and, with the help of the pills, to try and behave as normally as possible. Then at a large bookstore reading, the decision was made for him.

As he was walking to the podium, his gait froze so that he staggered briefly, and he was forced to announce to the room that he wasn’t drunk—he just had Parkinson’s disease. Rather than feeling embarrassed, he felt relieved. Now to present himself without divulging his condition would seem like a lie of omission and a denial of who he was—or rather who he had come to be.

And who was that? For the first seven or eight years after his diagnosis, his symptoms had amounted to little more than a stiffness on the right side of his body that made him appear to limp slightly and that made his handwriting so pinched as to be illegible. These symptoms had been controllable with a couple of pills a day, and because he was taking less medicine back then, the side effects had been fairly minimal. But because Parkinson’s is, after all, progressive, it had indeed progressed.

At present, he had inconclusively concluded that living with a disease like Parkinson’s was an ongoing dance with yourself that you had to make up as you went along. Because you couldn’t help but see your “condition” as separate from your “self,” the disease divided you in two. Thus he’d become both the subject and object of his own attention, which is to say he’d developed a third-person relationship to himself. His once-so-familiar self had become a virtual stranger. And his condition was another country—a country that remained foreign even though it was where he now lived, a country whose weather he charted moment by moment and whose landscape was the landscape of his own mind, body, and soul.

This article appears in the August 2011 issue of The Washingtonian.