Monday, September 10, 2001, dawned with a forecast of continued warm temperatures and a few showers. It had been a cool summer by Washington standards, and a wet one. August alone had seen more than six inches of rain.

Thousands of Washingtonians had spent the weekend outdoors, taking advantage of the nice weather. On Saturday, September 8, the first National Book Festival had brought 25,000 literature lovers to the East Lawn of the Capitol. Historian David McCullough had talked about his latest book, a biography of John Adams, which President George W. Bush recently had finished reading. McCullough’s afternoon talk in the Library of Congress was so popular that festival organizers had to turn away dozens of fans.

Sunday was the 23rd annual Adams Morgan Day festival, which drew 90,000 people to one of Washington’s most diverse neighborhoods for an afternoon of eating and listening to music.

On Monday morning, it was back to work and back to political battles that had been suspended in August as many congressional staffers headed for the beach and the President and First Lady spent a month at their ranch in Crawford, Texas. President Bush had taken time from his vacation for a televised address—just the second of his presidency—to announce his policy on limiting stem-cell research.

Meanwhile, Democrats and Republicans were arguing over whether the country could afford Bush’s tax cut, enacted earlier in the year, or whether consumers needed another in order to help revive an economy that was still faltering amid the wreckage of the dot-com bust. The unemployment rate was on the rise—from 3.9 percent in September 2000 to 4.9 percent a year later.

In mid-August, 92 million IRS rebate checks had been mailed to taxpayers—up to $300 for unmarried filers and up to $600 for those filing jointly. The administration hoped people wouldn’t hang on to the money for long. Stores such as Home Depot were so eager to attract customers that they offered to cash the tax checks for them.

Amid partisan bickering over the federal budget, Morton Kondracke, in his syndicated column published on September 10, offered “a proposal that’s almost certainly too high-minded to be adopted: Democrats and Republicans should work together this year to get the economy growing again and fight next year about the nation’s longer-run fiscal future.”

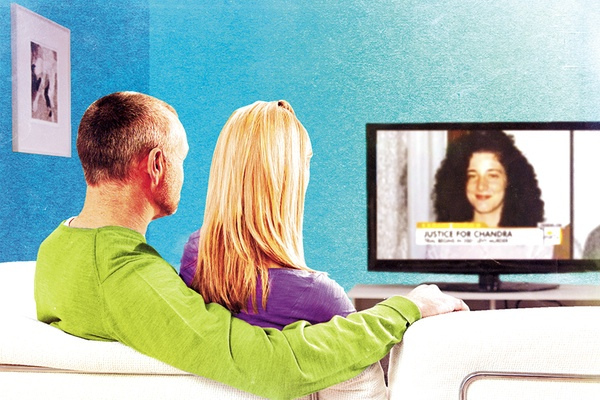

But the biggest stories of the day—of the entire summer up to that point—were of more immediate concern: a panic-inducing spate of shark attacks along Atlantic beaches and the disappearance of a young Capitol Hill intern, Chandra Levy, and the lingering cloud of suspicion around California congressman Gary Condit.

American Pie 2, Shrek, and Pearl Harbor were hits at the box office, and many were eagerly awaiting the November release of the first film in the Harry Potter series. Washington didn’t have a baseball team, but fans were fixed on Barry Bonds, who was closing in on Mark McGwire’s all-time record of 70 home runs.

Attorneys at the Justice Department were wrapping up their antitrust lawsuit against Microsoft. Media giants Time Warner and America Online were nine months into the largest corporate merger in history. And at the US Patent and Trademark Office, final approval for a “method for node ranking in a linked database” had just been granted to Lawrence Page, cofounder of the three-year-old search engine Google.

• • •

In Stafford, Virginia, Navy lieutenant commander Pete Marghella stepped out the front door of his house at 4:30 that morning and looked down a gentle slope that led to the Potomac River. The air was cool and still. A good day for a run, he thought. He would have liked to squeeze in an afternoon jog on the Mall, but he’d be too busy at the Pentagon.

Marghella, chief of medical plans and operations for the Joint Chiefs of Staff, was preparing for a highly classified military drill the next day, called Operation Global Guardian, which would test the nation’s response to a nuclear attack. Marghella would be flying aboard a modified Boeing E-4 jumbo jet, the National Airborne Operations Center, known more commonly as the Nightwatch. In the event of a real war, it would serve as the Defense Department’s mobile command post. The drill would keep Marghella away from home for a few days, and he was told to prepare for “an austere living environment,” which, as a Navy man, he took to mean Army barracks.

In Springfield, Vicki Yancey was also getting ready for a big trip. She recently had been promoted at her job with a defense contractor, and her new responsibilities included business travel. That summer had been a productive one, with Yancey taking her first-ever work trip, to New Orleans. It wasn’t the best time of year to visit in terms of the weather, but she had come back with renewed confidence and loads of souvenirs for her family.

Business travel agreed with Yancey. On Tuesday she was heading to a conference in Reno. It had originally been set for August, but the planners had moved the date. Yancey was booked on a 7:45 am flight out of Dulles.

• • •

Politicians were arguing over whether the country could afford Bush’s tax cut, enacted earlier in the year. Some thought we needed another tax cut to jump-start consumer spending.

In Leesburg, Tim Hardison reported for his shift at the Washington Air Route Traffic Control Center shortly before 8 AM. Contrary to what people saw in the movies, the real action in air-traffic control wasn’t in towers at airports—it was in the Federal Aviation Administration’s 22 regional radar centers. At Washington Center, Hardison and 400 others handled flights from the middle of West Virginia east to the Atlantic Ocean and from New York to North Carolina.

Air-traffic control was like a relay race. Once a flight departed one of the region’s three big airports, it was handed off from the tower to a controller in Vint Hill, Virginia. When the plane was above 23,000 feet and 40 miles away from the airport, Washington Center took over. Just as in a baton pass, controllers were in contact with only one other person—or one center—at a time. Washington could talk to New York, New York to Boston, Boston to Washington, but there was no easy way for all the controllers to talk to one another at once.

As long as an airplane stayed on course, none of this posed a problem. In the event it went astray and the pilot was unresponsive, controllers usually assumed that the plane was having navigational or communications problems. They would monitor and track the aircraft and notify surrounding facilities, and if they were unable to reestablish contact, military aircraft could intercept the plane and try to make visual contact with the pilots.

The intricacies of domestic air traffic were well known to Jim Wilding, president and CEO of the Metropolitan Washington Airports Authority, who spent the morning bounding around a convention center in Montreal. He was attending the annual meeting of the Airports Council International-North America. On September 10 and for the next couple of days, the director of nearly every airport in the United States was scheduled to be in Canada.

Among the most pressing concerns the directors discussed was how to cut down on jet-engine noise in neighborhoods near airports. Wilding was in the midst of a major airport construction project. Work had wrapped up a few years earlier on a new terminal at Reagan National. Now, at Dulles, crews were moving into high gear on an extension of the main terminal. Included in the plans was an underground train to replace most of the outdoor “mobile lounges” that moved passengers across the concrete expanse of the airport.

Wilding was looking forward to the improvements. But one critical component was beyond his control. Airlines, not airports, managed the outside contractors who checked passengers and their baggage before they boarded. In the previous seven years, a series of federal audits had found serious flaws in the screening system, yet there were few improvements.

Like a lot of his colleagues at airports across the country, the private screeners didn’t give Wilding much confidence. But he didn’t have an easy answer for the problem.

***

Back in Washington that Monday morning, Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld tried to jar the Washington news cycle out of its summer haze. At 9:30, he joined Air Force general Richard Myers, the President’s nominee for chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, before a bank of TV cameras and reporters to declare the start of a new war—on the Pentagon bureaucracy.

“In this building . . . money disappears into duplicative duties and bloated bureaucracy—not because of greed but gridlock,” Rumsfeld said. “Innovation is stifled—not by ill intent but by institutional inertia.” Proving that his campaign to cut $18 billion in defense spending wouldn’t leave out headquarters, Rumsfeld said he would slash Pentagon personnel by 15 percent.

Meanwhile, Peter Bergen, a journalist and terrorism analyst, was working on a breaking story out of Afghanistan. Ahmed Shah Massoud, the political and military leader of the anti-Taliban Northern Alliance, had reportedly been attacked by suicide bombers posing as journalists. There were conflicting accounts about whether he had died. Massoud was a moderate Muslim and a potential US ally. If he were killed, it would strengthen the Taliban’s position and that of Osama bin Laden’s al-Qaeda network, which had been given safe haven in the country.

After contacting sources, Bergen was confident Massoud was dead. He was preparing to go on CNN, where he was working part-time as a terrorism analyst, to explain the importance of the assassination to viewers for whom Afghanistan’s bloody factionalism was not only hard to understand but of minor importance.

Bergen was one of the few Western journalists to have seen al-Qaeda’s leader up close. In March 1997, he’d produced the first television interview with bin Laden. Sitting in a mud hut in the mountainous Tora Bora region of Afghanistan, bin Laden drank tea and, in a barely audible voice, excoriated America’s policies in the Middle East.

A few weeks before the Massoud attack, Bergen had obtained a copy of a videotape in which bin Laden gave perhaps his clearest distillation of al-Qaeda’s philosophy. He condemned the presence of US military forces in Saudi Arabia and “the Arab rulers [who] worship the God of the White House.”

• • •

On August 17, Bergen wrote to his friend John Burns, a fellow terrorism chronicler at the New York Times, urging him to write about the bin Laden videotape. Already that summer, there had been chatter coming out of Yemen about possible attacks. In June, two men arrested in New Delhi said they were planning to blow up the visa section at the US embassy. The next month, the State Department warned of “strong indications that individuals may be planning imminent terrorist actions” against American interests on the Arabian Peninsula.

“Clearly, al-Qaeda was and is planning something,” Bergen told his colleague.

Burns watched the tape and, after checking with his own sources, wrote an article for the Times. It ran September 9 on the newspaper’s Web site, under the headline on videotape, bin laden charts a violent future. Burns’s editors expected to put the story in the newspaper. But because space was tight in the September 10 edition, they spiked it. The article was later expunged from the Web site, because it was Times policy not to archive any Web story that didn’t run in print.

At lunchtime, Delaware senator Joe Biden, chairman of the Foreign Relations Committee, sat down at the head table in the ballroom of the National Press Club. Biden had ascended to the committee’s top slot when Democrats gained control of the Senate in the spring after Vermont’s Jim Jeffords left the Republican Party and became an independent.

Richard Ryan, Washington correspondent for the Detroit News and president of the National Press Club, welcomed guests and noted that Dan Snyder, owner of the Washington Redskins, would be the speaker on October 2.

“Can I come to that one?” Biden joked.

The senator spent much of his speech criticizing the Bush administration’s proposal to build a national ballistic-missile defense system. He said it was much more likely the United States would be attacked by terrorists than by a country with a missile.

By midafternoon, the temperature in Washington had reached 87 degrees, with the promise of cooler weather and clear blue skies the next day. Tourists had been scarcer on the Mall since Labor Day, but 4,800 people still shuffled through the Jefferson Memorial and 8,000 visited the Lincoln that day.

Across Washington, workers were taking a coffee break, getting ready to pick up their kids from school, or counting down the minutes to happy hour. Two blocks from the White House, DC protestors outside the newly reopened Wilson Building were angry over federal efforts to stop the city’s needle-exchange programs, its abortion services, a referendum to legalize medical marijuana, and the extension of benefits to the gay partners of city employees. DC police were searching for a three-year-old girl and her teenage babysitter who’d failed to bring the child home Sunday.

In Northern Virginia, citizens were reacting enthusiastically to a proposal to convert Lorton prison into a soccer complex, and the state House of Representatives voted to rename two post offices—in Annandale and Mount Vernon—after former representatives from the region, a Democrat and a Republican who’d once been political rivals.

• • •

Around 3 PM, Hani Hanjour checked in at a Marriott Inn in Herndon, about five miles from Dulles. He was joined by Nawaf al-Hazmi and al-Hazmi’s brother, Salem, as well as two other men.

Hanjour had come to the United States in 1991 from Ta’if, Saudi Arabia. He enrolled at the University of Arizona, where he studied English as a second language. He was a devout Muslim and had already been to Afghanistan once, as a teenager in the late 1980s, to take part in jihad.

While in Arizona, Hanjour had associated with several extremists who later would become the subject of counterterrorism investigations by US authorities. Some of them had trained with him to become pilots. Others had connections to al-Qaeda and had been trained at the group’s camps in Afghanistan. Hanjour was at one of those camps in the spring of 2000 when a senior member of al-Qaeda, possibly bin Laden himself, learned he was a trained pilot. He was told to report to Khalid Shaikh Mohammed, a member of bin Laden’s inner circle, who taught Hanjour how to communicate in code words.

In June 2000, Hanjour went home to Saudi Arabia, and three months later he obtained a US visa. On December 8, he touched down in San Diego, where he met up with al-Hazmi, whom the CIA had been tracking for a long time.

Hanjour and al-Hazmi left the San Diego airport and drove to Mesa, Arizona. They stayed there a few months while Hanjour took refresher classes at his old flight school and trained in a Boeing 737 simulator. In the spring, Hanjour and al-Hazmi headed out on a cross-country drive, arriving in Falls Church in April 2001.

The morning of September 10, Hanjour had checked out of a Budget Host motel in Laurel, not far from the headquarters of the National Security Agency. That day, the agency’s global eavesdropping system intercepted coded phone conversations, likely among al-Qaeda operatives overseas: “The match begins tomorrow” and “Tomorrow is Zero Hour.” Analysts didn’t translate the messages into English until September 12.

• • •

President Bush touched down in Sarasota, Florida, Monday evening. He’d spent the afternoon in Jacksonville and visited an elementary school, where he promoted his No Child Left Behind initiative. He planned to visit another school the next day.

David Morris, chief White House correspondent for Bloomberg News, had been traveling with the President all day. There were protestors in Sarasota along President Bush’s motorcade route. Morris knew that wasn’t unusual. To some Floridians, Bush was still “the accidental President.”

Morris decided to join a group of reporters for dinner and was talking with Ann Compton of ABC News when Ari Fleischer, the White House press secretary, pulled him aside. The President was planning to go running the next morning and wanted Morris’s Bloomberg colleague, Dick Keil, to join him. Morris passed the message along to Keil and continued with his dinner.

Tuesday would be a slow news day, Morris figured. Just another education event. But maybe it wasn’t such a great morning for a run. Sarasota was experiencing a red tide, a phenomenon in which blooms of poison-producing algae appear off the shore and change the color of the water. Morris thought the entire area reeked of fish.

Back on Capitol Hill, Charles Wood, a bomb technician and trainer with the US Capitol Police, was finishing his lesson plan for a field trip on the 11th. Wood was taking two dozen new recruits, almost all in their early twenties, down to the Capitol Police’s explosives-testing range in Quantico. Everything the rookies knew about bombs they’d seen in the movies and on television. Wood wanted them to feel the heat and the blast pressure from a real explosive device and to learn to respect the damage that someone could cause with a simple homemade bomb.

Wood trained the recruits to be ready for all manner of threats but to keep an especially sharp eye out for VBEDs—vehicle-borne explosive devices. Fertilizer-based bombs had been planted in vehicles for the 1993 World Trade Center attack and the 1995 bombing of the Murrah Federal Building in Oklahoma City. Capitol Police were especially concerned about car bombings of public buildings. There were few more enticing targets for terrorists than the US Capitol, Wood told the recruits.

That’s how Andy Maybo had been trained. A 25-year-old officer, he was assigned to patrol office buildings for the House of Representatives. But right now, the big problem for Hill police wasn’t bomb threats. There had been a rash of bicycle thefts over the summer. Officers were routinely summoned to investigate stolen office equipment and personal property.

Maybo had always wanted to be a law-enforcement officer. He’d grown up in Parsippany, New Jersey. His dad had season tickets to the New York Giants. Maybo liked living in Washington because it was only a few hours from New Jersey and a job with the Capitol Police guaranteed he’d never be transferred farther away from home. He still had close friends there, including some who worked for the New York City Fire Department.

On September 10, Maybo was scheduled to work the 3 to 11 PM shift, but he asked for the night off. That evening, he got together with friends in Arlington to watch the Giants play the Broncos in the Monday Night Football game. The Giants lost.

• • •

On The NBC Nightly News With Tom Brokaw,the economy led the broadcast. Reporter David Gregory, traveling with the President in Florida, said Bush had wanted “to talk about education, but his advisers know, with the economy in a tailspin, Mr. Bush’s initiatives on this and other issues are drowned out.”

Also in the news, Almon Glenn Braswell, the “herbal-supplements king” who spent time in prison for marketing phony baldness cures and who was later pardoned by President Clinton, had appeared before a congressional hearing investigating anti-aging products and took the Fifth Amendment. And a study on child exploitation had found that more children were being forced into prostitution and the pornography business than previously known. The study warned that the Internet posed a rising threat; millions of children were being exposed to unwanted sexual materials online.

NBC also ran a tribute to a Boeing 707, tail number SAM 27000, that had flown 1.3 million miles in service to seven Presidents, who called the plane Air Force One when they were aboard. The plane had made its final flight—without President Bush—before being moved to a hangar in San Bernardino, California, and eventually to the Ronald Reagan library. In 1974, Richard Nixon had flown the plane to California after he resigned. In mid-flight, the plane’s call sign changed from Air Force One back to SAM 27000 when Gerald Ford took the oath of office. Nixon asked the flight attendant to bring him a martini.

Brokaw signed off from New York: “I’ll see you back here tomorrow night.”

• • •

Chandra Levy’s disappearance was one of the summer’s big stories. Also in the news: shark attacks at ocean beaches.

In DC, Mayor Anthony Williams was heading home after a soiree hosted by the Nature Conservancy at the Corcoran Gallery of Art. He’d been feeling under the weather and he decided he’d take the 11th off.

Halfway across the country, Illinois state senator Barack Obama, who’d turned 40 a month earlier, was getting ready for a legislative hearing in Chicago the next morning.

• • •

As September 10, 2001, drew to a close, the measures of the day were dutifully logged. The sun rose at 6:45 and set at 7:24. More than 600,000 boarded a Metro train; many more were in cars. Twenty-one people died in the District; 37 were born.

Vicki Yancey sat at her computer until around 10 PM. A political junkie, she’d become a frequent commenter on Washingtonpost.com and in AOL political chat rooms. She’d grown close to an extended network of fellow commenters, whom she considered a kind of family.

She logged off and chatted with her husband, David, about their schedule for the next few days while she was in Reno. The Yanceys had had a new oven delivered a week earlier, and the electrician was coming Tuesday morning to hook it up. Vicki went to her youngest daughter’s room to say goodnight. The girl had just started her sophomore year at Robert E. Lee High School in Springfield. The Yanceys’ elder daughter had enrolled at Virginia Tech two weeks earlier. Vicki did some last-minute packing and went to bed around 11:30.

Back home in Stafford, Pete Marghella packed his suitcase and an overnight kit. He’d participated in dozens of military drills, but he couldn’t shake a creepy feeling about Global Guardian, the operation to test the nation’s response to a nuclear attack. It seemed like such a relic of the Cold War. He kept thinking about the 1983 TV movie The Day After, about a real nuclear attack on the United States. Marghella was just 22 when the movie aired. Now he was married with three daughters, and he’d signed official papers vowing that in the event of a war, he would deploy with his team and leave his family behind.

“I hate to do this,” he told his wife, Zenaida, “but this is one of those times I can’t tell you where I’m going and how long I’ll be away.”

Zenaida had long ago stopped being impressed by her husband’s job. “Yeah, whatever,” she said. Anytime Pete announced he was heading to the White House or briefing the chairman of the Joint Chiefs, Zenaida would say she was lunching with the queen of England. She liked to remind her husband he was still just a boy from the Bronx.

Zenaida was asleep when Pete left for the Pentagon the next morning at 4:30. He recalls that he kissed her goodbye and whispered, “I love you.” She didn’t stir.

• • •

Vicki Yancey called from Dulles on Tuesday morning at 7:30. There’d been a snafu with her schedule, she told her husband, and she couldn’t get on her flight. “Come home,” said David, who’d just let in the electrician. “It’s not your fault.”

Vicki didn’t want to miss the conference in Reno. She hung up and made some calls. A few minutes later, she called back to tell David she’d managed to get a seat on American Airlines Flight 77, at 8:10. David recalls that, in what would be their last conversation, she sounded pleased with herself for finding a way to keep her plans.

Hani Hanjour, Nawaf al-Hazmi, and three traveling companions checked in at Dulles. Hanjour and two others were flagged by airline security but were let go. At the passenger checkpoint, three of the five men set off the metal detector. They were all cleared to the gate area after walking through a second metal detector or receiving a physical inspection by a security contractor with a metal-detecting wand. Al-Hazmi went through the checkpoint shortly after 7:35. Apparently, none of the guards was aware of the object protruding from al-Hazmi’s back pocket. Evidence would later suggest it was a knife or a box cutter. About ten minutes later, the five men boarded Flight 77. Al-Hazmi joined his friend Hanjour in the first-class cabin.

At the FAA’s Washington Center, Tim Hardison was attending the morning meeting in the air-traffic manager’s office. The phone rang. An aircraft had just been reported hijacked. Hardison walked out to the control room. He could see a plane on radar heading toward New York. Then it disappeared. Maybe it had gone below radar, he thought. The control room had no TV monitors.

At the Pentagon, Marghella sat in his office on the outer “E-ring,” the most prestigious real estate in the building because it had windows facing outside. In the next room, his bosses were watching the Today show, as they did every morning. “Get a load of this!” he heard someone shout. Marghella went over and saw smoke billowing from one of the World Trade Center towers. He remembered a photograph he’d seen in an old Life magazine from the 1940s: The Empire State Building in flames after a B-25 bomber crashed into it.

“Son of a bitch—a plane flew into the building!” Marghella said.

A two-star admiral looked at him incredulously. “Don’t be stupid,” he said. “They don’t let planes fly that close to buildings in New York airspace.” A moment later, the men watched as a second jet appeared on the TV screen heading toward the Twin Towers.

At Washington Center, Hardison and the other controllers began an emergency procedure unprecedented in the history of air travel—guiding every plane in their airspace immediately to landing at the nearest airport. He had called his wife and asked her to turn on CNN and tell him what was happening in New York. Washington Center was picking up another plane on its radar. It was American Flight 77, bound for Los Angeles, which the controllers had handed off earlier to Indianapolis as it made its way west. The pilot had reversed course and was heading east.

In the Pentagon, Marghella, the admiral, a colonel, and a civilian contractor stood around the television as the second tower burned. The civilian contractor broke the silence. “That’s just the first hit,” he said. “America is under attack. They’re coming for Washington.”

This article appears in the September 2011 issue of The Washingtonian.