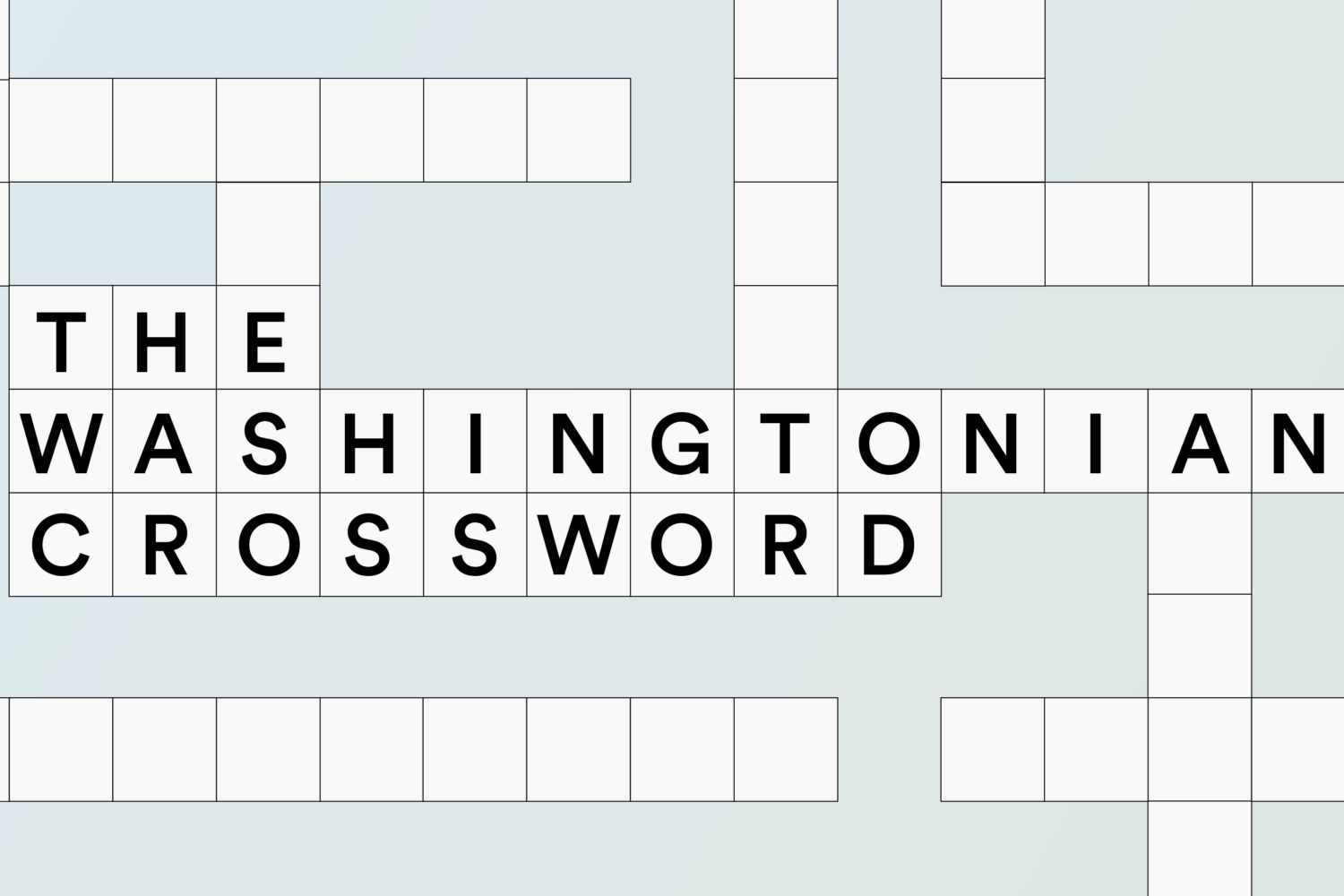

Brandon J. Dirden as John Nevins, Thomas Jefferson Byrd as Sheldon Forrester, E. Faye Butler as Wiletta Mayer and Marty Lodge as Al Manners in the Arena Stage at the Mead Center for American Theater production of Trouble in Mind. Photograph by Richard Anderson

☆☆☆ out of four

Actors frustrated at being typecast have a lot to learn from Trouble in Mind, Alice Childress’s 1955 play about a company of black and white actors rehearsing a Broadway play. Childress based the play on her own acting experiences (she struggled with the limited roles available to black actors in the ’50s), and while one would hope that 56 years on, the play is hopelessly out-of-touch, it’s sadly still an insightful, alternately funny and wrenching look at the soft bigotry of good intentions.

The scene is set in a large, brick-walled rehearsal space somewhere in New York City, where Wiletta (the ever-resplendent E. Faye Butler) is the first cast member to arrive. Both Wiletta and fellow actor Millie (Starla Benford) have made successful careers playing black women with floral (Petunia, Gardenia) and semi-precious (Pearl, Opal) names—names that are considerably richer than the characters they nevertheless gamely portray. The African-American cast also includes Sheldon (Thomas Jefferson Byrd), an inadvertently funny, deep-voiced ham, and John (Brandon J. Dirden), a young actor starting out. “Why you wanna act?” Wiletta asks him, on discovering they come from the same small Virginia town. “Why you don’t wanna make something of yourself?”

Also in the play—a hopelessly clunky lemon with an offensively misguided anti-lynching message—are white actors Judy (Gretchen Hall), a wide-eyed recent graduate of Yale Drama, and Bill (Daren Kelly), who plays Judy’s father, the owner of a plantation. The show is directed by Al Manners (Marty Lodge), a man so impervious to empathy and unpleasantly physical that it’s hard not to recoil every time he walks onstage. During rehearsal, Al alternately terrifies and gropes Judy, screams at his assistant, and insists on repeatedly kissing Wiletta on the forehead, to her increasing disgust.

And yet, despite all his unpleasant attributes, Al seems to be a surprisingly skilled director, enticing a passionate, fiery gospel solo from Wiletta, and awakening in her some long-buried dissatisfaction with how things really are. Wiletta’s transformation from a blasé, nonchalant performer to a deeply principled, deeply unhappy actor is at the core of the play, and it’s the only thing that doesn’t quite work. In one of the opening scenes, she informs John casually about the bigotry of white audiences and directors, telling him how best to present himself without making anyone uncomfortable. But this well-sketched cynicism turns into a veritable revolution when Wiletta suddenly objects to a plot device she finds unrealistic, and her transformation is so sudden that we barely have time to acknowledge how it happens.

Director Irene Lewis (who also staged the show at Baltimore’s CenterStage) has assembled an outstanding cast, and the chemistry between the actors at certain points is palpable. But at times, some important points feel slightly rushed. In contrast, the strongest moment of the play is a tragic tale told by the usually jovial Sheldon, with such a measured and thoughtful pace that it’s downright heartbreaking. “Everyone’s a stranger, and I’m the strangest of all,” says a drunken Judy after he finishes, summing up the gist of the play. Or, as Al tells Wiletta, “The American public is not ready to see you the way you want to be seen.” Childress’s play was an antidote to that half a century ago, and it’s still helping us take the blinkers off.

Trouble in Mind is at Arena Stage through October 23. Tickets ($40 and up) available at Arena’s Web site.