Of the hundreds of evenings Michael Kaiser has spent in a theater, opera house, or concert hall, one stands out. That was the night, he says, when his parents took four-year-old Michael and his older brother and sister to a performance of the Broadway hit The Music Man at the Majestic Theater on West 44th Street. Young Michael was mesmerized, especially during the first act when the character known as Marian the librarian—played by Barbara Cook in her first real hit—grows wistful on the porch of the modest home she shares with her mother in 1912 small-town Iowa.

“I would not be here today,” the Kennedy Center president told a Washington audience this year, “if she did not sing ‘Goodnight, My Someone’ and the scrim lit up behind her and I could see into the house. That was the most magical moment in the history of my life. And I decided I was going to spend my whole life getting behind that scrim.”

Now, more than half a century later, Kaiser controls a lot of scrims and more or less everything else that has gone up, down, or sideways on each of the Kennedy Center’s nine stages for the last decade.

As chief of Washington’s preeminent performance venue, the soft-spoken Kaiser arguably has a stronger role than anyone in setting Washington’s cultural agenda. His grip grew firmer July 1 when the fiscally faltering Washington National Opera came into the Kennedy Center’s firm embrace, as the National Symphony did in 1986.

With the departure of world-famous tenor Plácido Domingo as the opera’s general director and singular public image, Kaiser’s views will be reflected in even more of the Kennedy Center’s 2,000 performances a year. But planning and promotion in the white-marble box beside the Potomac, with its $180-million annual budget, has become only part of the Kaiser story. With his worldwide advocacy of “good art, well marketed,” Kaiser has become a figure on the world stage.

Kaiser, according to Philanthropedia, a guide to nonprofit institutions such as the Kennedy Center, is the official cultural ambassador for the State Department’s Cultural Connection Program. He has made tough-love visits all over this country and to others, from Argentina to Zimbabwe, meeting with arts leaders from more than 70 nations.

He flew to Cairo and the West Bank to stimulate artistic planning as well as to foster Kennedy Center cultural exchanges with the Arab world. He landed in Baghdad aboard a military plane with a ruptured fuel line—“I was in my little three-piece suit surrounded by soldiers,” he recalled for a South Dakota audience—but was soon at a chamber-music concert, with armed guards, in one of Saddam Hussein’s old palaces. “It was a bit surreal,” Kaiser says, “but it made the point that art is everywhere.” And it led to a joint performance by the National Symphony and the Iraqi National Symphony at the Kennedy Center.

Kaiser thinks his many travels enhance the center’s role as the national cultural crossroads envisioned in the 1958 act that established the performance complex, which became the “living” memorial to President John F. Kennedy after his assassination in 1963. The center opened in September 1971, transforming the performing arts in a then-stage-starved Washington.

Next: Kaiser doubles fundraising efforts

Since the US economy hit the skids in 2008, Kaiser has traveled to 69 American cities, at least one in each state, as part of an Arts in Crisis tour. On his 83,000-mile trek, he told 11,000 arts leaders that the worst thing they could do in a recession was to cut back on performances and promotion.

High-flying ministrations to the arts worldwide are a neat trick for a guy whose own most memorable public performance might have been about a half century ago when he dropped King Esther’s crown during a Purim play in suburban New York. Kaiser took steps toward an operatic career but stopped training as a baritone while still in his teens. He says he hasn’t sung in years.

Now Kaiser is most mellifluous with potential contributors. He charms millions from donors by matching their passion for, or whipping up an interest in, one of his music, theater, and dance extravaganzas or—increasingly—arts management. He says he knew that not all his top contributors would be interested in this year’s international festival, Maximum India, at the Kennedy Center. But he won the support of the Tata group, India’s giant multinational conglomerate.

“It’s the big, special stuff we do that makes people say, ‘I want to be part of that,’ ” Kaiser told arts managers at a Kennedy Center seminar last spring. Soon after arriving at the center in 2001, he conceded to the New York Times: “There’s a P.T. Barnum element to what we do.” And he still believes it. “We are show people,” he says.

During his ten years as Kennedy Center chief, fundraising has more than doubled. Contributions make up about 40 percent of the annual budget, or just over $70 million. The endowment is about $95 million, which appreciated by 10 percent last year, with about half of the throw-off going to center programs. The Kennedy Center budget has grown by 60 percent during his tenure.

Operating in the national capital with a board largely appointed by the President, Kaiser tries to remain apolitical. While the arts are often seen as a Democratic preserve, Kaiser has developed strong ties with some A-list Republicans.

A major coup was securing a $22.5-million gift—the largest single grant of Kaiser’s tenure—in 2010 from Betsy and Dick DeVos of Grand Rapids, Michigan. Betsy DeVos is former chair of the Michigan Republican Party, and Dick DeVos was the 2006 Republican candidate for governor who lost to Democrat Jennifer Granholm. Their wealth stems principally from the Amway direct-sales company cofounded by Dick DeVos’s father. An initial $2.5 million went to short-term operation of the Kennedy Center’s newly renamed DeVos Institute of Arts Management, with $20 million going to an endowment for the institute.

A recent $20-million gift, in two $10-million pledges, came from the very Democratic billionaire David Rubenstein, a cofounder of the Carlyle Group private-equity firm and chair of the Kennedy Center board.

For all his charm, Kaiser can be ruthless. “Separate your winners from your losers,” he told art managers from around the country in April. “Drop those [losers] and focus on the ones who will” make major donations. Often, he says, a board member is relieved to be asked to step aside, but Kaiser concedes that there are some famous people “who will never speak to me again.”

Kaiser is one of the nation’s highest-paid arts managers—he made $1.1 million in salary and benefits in the fiscal year ending September 30, 2010, according to the Kennedy Center’s filing with the IRS.

As the New York Times surveyed salaries at top arts institutions last year, Stephen Schwarzman, then chair of the Kennedy Center board, pointed out that Kaiser had earned the maximum permissible bonus of $150,000. “The performance has been terrific,” Schwarzman said, and the bonus was tied to “outcomes,” including increased attendance and consistent operational surpluses.

Kaiser intended to remain as KenCen president for no more than ten years, but last year he and the board of trustees agreed on a three-year contract extension, through 2014.

His tenure has been “a huge success, both from the entertainment side—the performance side—as well as in the box-office side,” says Kenneth Duberstein, a former vice chair of the Kennedy Center board and a prominent lawyer/lobbyist since his days as President Ronald Reagan’s chief of staff. “The Kennedy Center has become a destination now for the performing arts.” Staged attractions, including a free daily performance on the Millennium Stage in the center’s Great Hall, draw about 2 million people a year, and another 1 million come just to see the building, with its spacious halls and riverside vistas.

Government payments for capital improvements, upkeep, and educational programs amounted to more than 10 percent of the Kennedy Center’s budget until this year’s federal-spending reductions. Some federal cuts seem inevitable to Kaiser. “You won’t hear me whining about it in public,” he says. He’ll just bear down on fundraising and consider small trims.

The most vocal complaint came from advocates of an arts program for the disabled, whose staff was cut midsummer from 35 to 8. The budget for VSA—the arts-and-disability organization once known as Very Special Arts—was cut from $9 million to $5 million. A Kennedy Center spokesman says the staffing cut allowed a smaller cut in programs, the style of retrenchment that Kaiser has said he generally favors when required.

Kaiser accepts that governmental arts funding will never be an easy sell in the United States. “Our country was founded by the Puritans,” he says. “They thought music and dance were evil . . . and we’ve had separation of arts and state.”

Next: Critics question Kaiser’s strategy

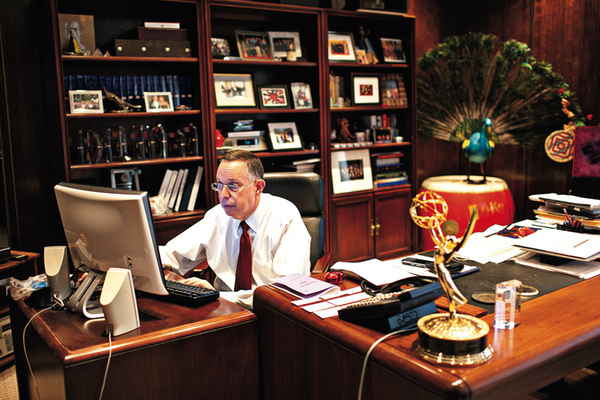

Kaiser’s day begins at 4 am, and he’s usually in his office by 7.

Kaiser has become a national beacon for struggling arts companies. He has traveled repeatedly to New Orleans since Hurricane Katrina, primarily to consult with the Louisiana Philharmonic, whose old home, the Orpheum Theater, was severely damaged in the 2005 storm. His first call offering help to the orchestra’s executive director, Babs Mollere, was humbling. “I don’t know who you are,” Mollere told him.

But Mollere says Kaiser displayed “the first attribute of success—he showed up.” And Kaiser has returned during subsequent hardships. “He forthrightly helps you to look at what you’re dealing with.”

He has taken a similar message around the country. “I’ve never seen a budget I can’t cut, but it’s not in art and it’s not in marketing,” Kaiser said in Santa Fe, according to the New Mexican newspaper. In South Dakota, Kaiser said he was “concerned that arts organizations facing the recession were going to make poor choices. . . . I think the secret is to abandon the notion that you can save your way to health. Arts organizations don’t get healthier by getting smaller and smaller and smaller.”

Kaiser’s aim is to keep beleaguered arts managers focused on why their organizations exist. Andrew Taylor, director of the Bolz Center for Arts Administration at the University of Wisconsin and discussion leader on a “crisis” tour stop, says Kaiser “inspires a lot of leaders to remember that they’re in an artistic organization and that’s the core of their job.”

Kaiser is paterfamilias to hundreds of young arts administrators who take part in the educational programs he oversees at the Kennedy Center. A primary aim is to remind younger managers what the arts are about. “What we’re in the business of is dreaming,” Kaiser says. “We get beaten down so by money, we quit dreaming.”

He’s not loath to criticize what he sees as bad advice, especially deep cuts in performances. Hearing the guidance one theater group was given, Kaiser grabs his tie, yanks it above his head like a noose, and says: “Your consultant is wrong.”

Kaiser, 58, came to the Kennedy Center after 15 years of rescuing performing organizations. During successive tenures, he eliminated a deficit of $125,000 at the Kansas City Ballet, $1.5 million at Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater, $5.5 million at American Ballet Theatre, and $30 million at the Royal Opera House in London, troubled home to two artistic lodestars, the Royal Opera and the Royal Ballet.

Kaiser has been dubbed the “turnaround king,” a moniker he’s happy to accept, titling one of his arts-management books The Art of the Turnaround. The Chicago Tribune called him “a spitfire,” which he says is not true but wishes it were: “I think I’m very focused—I don’t think I’m very tough.”

The chief rap against Kaiser, as presented in a multi-story blast from Washington Post critics in March, is that Kennedy Center programming is too safe.

“The Kennedy Center is huge,” Kaiser replied in an Aspen Institute appearance in Washington nine days after the Post barrage. “We have to serve many different communities and many different interests, and it would be inappropriate for us to only focus on what the arts police want.” Such critics, he said, “really are the most interested in the most cutting-edge and dismiss everything else.”

Post classical-music critic Anne Midgette belittled a festival planned for next spring featuring music of Vienna, Prague, and Budapest as “doing the expected where classical music is concerned.”

Midgette echoed objections raised earlier by her husband, critic/composer Greg Sandow, on an Artsjournal.com blog. Sandow said next year’s festival won’t feature music being created in those cities now but rather “safe, familiar, not exactly fresh classics, music premiered in those cities in centuries past.”

“As far as I know,” Sandow said, Kaiser “doesn’t do what he preaches.”

Kaiser disagrees: “We attempt very challenging programming and surprising programming. And that programming is very broad and very diverse.”

In awarding Kaiser an honorary doctorate the day after the Post’s assault, Georgetown University praised his “profound impact” on the nation’s development of a “rich and diverse array of cultural products.”

Kaiser ticks off highlights of his tenure, beginning with an unprecedented festival that packaged six Sondheim musicals from May to September 2002 and continuing to this year’s Follies, now enjoying an acclaimed Broadway run that was initially uncertain due to its large cast (41), orchestra (28), and crew (including 14 dressers).

The financing of Follies illustrates the difference between for-profit performance organizations and a public/private enterprise such as the Kennedy Center. Even if every seat had been sold for the show’s six-week run here in May and June, there would have been a $2-million deficit, Kaiser says. The shortfall was covered by money Kaiser raised for the show and by the center’s operational surplus, which has totaled $50 million in his ten-year tenure. “We had no cash here when I got here,” Kaiser notes, but now there is a working capital reserve.

Kaiser implies that critics in the media are happy only when their particular tastes are catered to. He cites this year’s Maximum India festival, next year’s “street art” festival, and an earlier a cappella choral festival as examples of Kennedy Center presentations “that don’t fall into the rubric of a theater critic, of a music critic, or a dance critic. But it’s happening, it’s unusual. I can’t think of another arts center that’s done that.” Kaiser says the India festival sold more than twice as many tickets as expected.

Kaiser brushes off carping about the Kennedy Center’s perennial cash cow, Shear Madness, a whodunit set in a hair salon with audience participation and improvisation. It’s not Shakespeare, but it is, Kaiser contends, “a wonderful introduction to the theater for a whole lot of kids who come here every spring.” Ticket sales net about $500,000 a year and help pay for non-revenue programs such as education ventures and the free Millennium performances.

Kaiser isn’t uncritical about Kennedy Center programming over his decade. “There’s a lot that we’ve done that I didn’t like,” he says, singling out Carnival!, the center’s 2007 revival of a 1961 Broadway musical based on the movie Lili. “I budget for failure. If you never have a failure, you haven’t taken enough risks.”

Next: How the Turnaround Artist earned his nickname

Kaiser’s job, it’s often observed, is his life. He gets up at 4 am to read newspapers, work on e-mail, and run five miles on a treadmill: “I hate it, but it’s good for me.” He tries to get to bed by 8 a couple of nights a week, but if he attends a performance, 10:30 or 11 is more likely.

He walks from his apartment in DC’s West End to the Kennedy Center and is ready for a daily 7 am meeting with another early riser, marketing chief David Kitto, who came to Washington from New York’s Carnegie Hall. They discuss strategy for getting the word out, including advertising campaigns, for every program on the center’s schedule.

How Kaiser came to the arts may shed light on why the concept of “family” crops up often in his discussion of operational staff and performers at the Kennedy Center and elsewhere. There’s not only the story of his family’s long ago visit to The Music Man, where he was inspired to spend his life “getting behind that scrim.”

Kaiser says his parents, who ran a lumber business in New York, were “middle middle class” but interested in the arts from childhood—his mother in Berlin and his father in Breslau, then in Germany but now the Polish city of Wroclaw. His parents, who still live in suburban New York, left Germany after the rise of the Nazis. His paternal grandfather refused to emigrate and died in the Holocaust.

His paternal grandmother married a violinist in the New York Philharmonic and sometimes took her grandson to Saturday rehearsals. At age three, he began lessons on a quarter-size violin. “It had a profound effect on me,” Kaiser recalls. “To this day, when I hear a piece of classical music, standard repertoire, I can sing you virtually the whole thing from beginning to end. But I can’t always tell you if it’s Tchaikovsky’s Third Symphony or Fourth Symphony.”

Kaiser attended Philharmonic rehearsals in the heyday of music director Leonard Bernstein. “My first dog”—a standard dachshund—“was named Lenny,” he recalls.

Performing came naturally to Kaiser. He was the captain in a third-grade production of H.M.S. Pinafore. His father made epaulets and sewed then onto Kaiser’s blazer. “We still have it,” Kaiser says. As junior cantor at Temple Israel in New Rochelle, he played King Ahasuerus. “My father made the costume—a big crown. We still have that, too.” During the only performance, Kaiser dropped Queen Esther’s crown. “It was a very big blow to my ego that I had been so clumsy.”

The summer before his senior year in high school, Kaiser attended music camp at Interlochen, Michigan. Back in suburban New York, Kaiser’s father drove him on Saturdays to classes at the Manhattan School of Music.

Kaiser was accepted for vocal training in several college-level programs, auditioning with “Quia fecit mihi magna,” from Bach’s Magnificat.

“I decided at the last minute that I really wasn’t ready for them,” Kaiser says. He began college at MIT, where the choral director “recognized I had some modest amount of talent.” In the choral program at the Tanglewood Festival, he studied voice with opera soprano Phyllis Curtin.

Kaiser auditioned for the college-level program at the Manhattan School of Music but wasn’t accepted. “It turns out they had no spaces,” Kaiser says. “Still, it was a devastating blow. I decided if I wasn’t good enough to get into the Manhattan School of Music, I wasn’t good enough to have a career. I was 19.”

Kaiser graduated magna cum laude from Brandeis with a degree in economics and a minor in music. He has a master’s from MIT’s Sloan School of Management, where his thesis was a study of the then-infrequent sharing of opera productions by regional companies. “I knew I wanted to run an opera company,” he says.

A person who has worked with Kaiser says he isn’t a screamer but “can get a little louder and more intense.” A 2000 article in London’s Independent called Kaiser “too thin-skinned,” which he later conceded. In London sometimes, he has said, “I would go home and have a good cry.” That’s what comes from getting pummeled in the press and by the public. After a performance for schoolchildren was canceled—at what Kaiser calls the lowest point of his London tenure—a teacher assigned students an essay on “why we hate the Royal Opera House.” One began, “Dear Mr. Kaiser, we wish you were dead.”

Along the way he was in analysis, but now, he exclaims with mock drama, “I’m cured!”

Kaiser’s time in London, where he joined the revolving door of chiefs for the Royal Opera House, came amid the costly rebuilding of its storied home in Covent Garden. He left earlier than most had expected but turned around not only the accumulated $30-million deficit but also some carping politicians and journalists.

Kaiser’s association with the arts here goes back three decades. While running his own Washington-based management consultancy in the early 1980s, he was invited to join the board of directors of what was then the Washington Opera. (“National” was officially added in 2004.)

“I became the worst board member in the history of the world because I really wanted to be a staff person,” Kaiser said at the Aspen Institute. “I was very young and very callow and very obnoxious. . . . It’s come full circle. . . . So now I’m finally back running the WNO, which is something I’ve wanted to do since 1983.”

Although the KenCen/WNO agreement was described as an “affiliation” when it was announced in January, Kaiser leaves no doubt as to how he sees his expanded kingdom. Who is head of the NSO and WNO? “I am,” he replies crisply.

The opera’s deal was resisted initially by some WNO board members but was a no-brainer to other supporters. “It is something that I thought made a great deal of sense for many years,” says Christine Hunter, a former WNO board chief. She believes the WNO is “in very good hands. I think he’ll be a marvelous overseer.”

To a New York Times blogger, WNO president Kenneth R. Feinberg called the move “a godsend.” He predicted that Kaiser’s tenure would result in more operas over a longer season.

Virtually no aspect of the WNO’s current season, which began in September with one of the biggest chestnuts of all, Tosca, can be considered daring. And Tosca is the newest of the five operas in the 2011–12 run, having premiered in 1900. Plus, Kaiser notes of this season, “there’s nothing American in it; it’s all European. So I would like to see a more diverse season—absolutely.”

About a month before the merger took effect, Kaiser and the WNO named a leading US stage director, Francesca Zambello, as the WNO’s artistic adviser, a new post. She has known Kaiser since working on productions at London’s Royal Opera House. “What we’re looking at is how to expand the role of opera at the Kennedy Center,” Zambello says. That’s likely to include musicals.

Zambello is the brains behind a production of Wagner’s massive, four-opera Der Ring des Nibelungen that was to be shared by the San Francisco Opera and the WNO. San Francisco presented three cycles of the Ring in June and July, but the WNO ran short of money and canceled not only the full cycles but also the staged version of the final work in the tetralogy, Götterdämmerung.

“There will be a Rin

g cycle,” Kaiser says during an interview in his office in the upper reaches of the Kennedy Center, but he won’t specify dates. “It will not be in my tenure,” he says—but he could raise the funding as something of a parting gift. Die Walküre is his favorite of the four Ring operas.

The Kennedy Center’s annual gala in April, a celebration of Kaiser’s decade at its helm, featured a string of tributes, including a video from Britain’s Prince Charles, who expressed gratitude to Kaiser for his “single-handed management and rescue of the Royal Opera House” and his “remarkable genius in sorting things out.”

As much as Kaiser talks about management of the arts, he can also talk about the emotions involved. For this year’s gala, he asked Barbara Cook, who still performs regularly in her eighties, to sing “Goodnight, My Someone,” which had electrified him in The Music Man all those years ago. She declined, saying she no longer sings it in public; but she did do another of her heart-stopping ballads, “This Nearly Was Mine,” from South Pacific.

In September, the center announced that Cook—finally, in the view of some of her fans—had been selected as one of this year’s recipients of the Kennedy Center Honors. A center spokesman said Kaiser had no official role in selecting the honorees. Cook is already on the Kennedy Center schedule for back-to-back performances next June, when she’ll be 84.

At the center gala last spring, Cook was unsatisfied with her sometimes raspy performance. She looked toward Kaiser in his box seat and said, “I’m sorry, Michael—I’m here but the voice is not.” Later in his onstage thank-yous, Kaiser recalled the time he first saw Cook at the Majestic in New York:

“The magic of the theater took hold of me that night and has never let go.”

This article appears in the November 2011 issue of The Washingtonian.