In the early hours of September 18, 2010, police found Ashley McRae in the back seat of a car on Bruce Place in Southeast DC with a bullet in her head. She was pronounced dead later that day.

Detectives were stumped.

“She was shot in Southeast,” says one, who can’t give his name because of police-department policy. “But she was from Columbia Heights. So the people in the neighborhood where we found her didn’t know her. They were not much help. There were no witnesses. No one was talking.”

On the streets of DC, trust in the police is fragile and talking to cops is sometimes punished as “snitching.” Finding witnesses who will come forward is always a challenge, especially so in the McRae case.

“We had some people call us from Columbia Heights and say they had seen her picture on Homicide Watch,” one of the detectives says. “They didn’t lead directly to a suspect, but the site definitely helped us in the case.” The people who called provided useful background information on McRae, an accounting student at DeVry University.

Police eventually arrested Damon Antonio Sams for the killing. He said he shot McRae by accident and was sentenced to ten years.

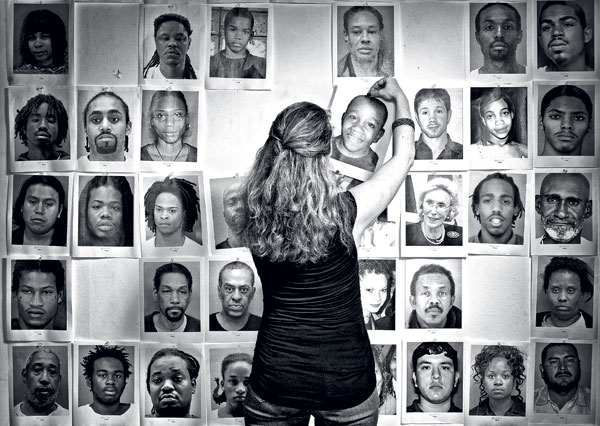

“That Web site brings to life some of the horror that goes on in the streets,” says another detective. “Showing the faces of the dead keeps the cases alive. Someone might see the face and call in. The right call can unlock a case.”

Murders Around the Region

Local homicide numbers haven’t fluctuated much in the past five years. DC saw 108 in 2011. Here’s the murder toll for other jurisdictions. (Some may have had additional homicides investigated by state agencies rather than local police.)

15Anne Arundel |

5Howard |

16Montgomery |

95Prince George’s |

1Alexandria |

0Arlington |

11Fairfax |

1Loudoun |

The murder rate in DC has been on a downward trend since 1991, when it peaked at 479, according to police statistics. By 2001, homicides had dropped to 232. In 2011, homicides fell to 108.

The police take credit for the drop, while many academics attribute the figures to a nationwide decline in violence and to higher incarceration rates. In DC, demographics play a role: The city has razed public-housing projects, poor people have had to pull up stakes, drug markets have moved to the suburbs.

Has Homicide Watch had any impact on murder rates?

“I think so,” says US Attorney Ronald Machen. “It used to be out of sight, out of mind. Now when an incident happens, you can see a real person who’s been killed. The more faces you put on the victims, the more people might have the courage to stand up and help law enforcement solve the case.”

Chris Amico believes that providing information about each murder will get readers to pay attention to the individual stories behind the statistics.

“When you go to our site,” he says, “I want you to have an emotional reaction.

“But I also want you to understand the crimes. Not in a general sense,” he says. “We’re not arrogant enough to think we can break the code on why people commit murder. But we do want to break through the stereotypes that all victims of homicide are disaffected youth who do drugs and come from broken households.

“We want people to come and see real narratives and draw truth from that.”

How has a year of watching homicides up close changed Laura Amico? Is she becoming numb?

“Not at all,” she says. “It’s made me softer in how I work with the people most impacted by the traumas. I feel a responsibility to people sharing with me what they go through in those moments. It forms a connection. I want to do right by them.”

Reporters who cover violent crime say they have to wall off their feelings from what they see. Is her wall still intact?

“Yes,” she says. “Reporting is reporting. I do it the way I always do it. But the comments get to me. The emotion can be so raw, I have to feel it. It’s a mixture of being gratified that people are able to open up, hope they will find resolution and support, and also heaviness in my heart for what they are going through.”

She’s surprised when people comment on Homicide Watch long after the crime. A year after one woman was killed, Amico wondered why hits on her page spiked.

“I realized it was her birthday,” she says. “These cases don’t end after the crime, the arrest, the conviction. They are part of people’s lives long after.

“I’m still a police reporter at heart. My heart is just a lot heavier.”

This article appears in the February 2012 issue of The Washingtonian.