Though steady rain and bursting dogwood promised rebirth, all Virginia seemed gray in that lush spring of 135 years ago.

Spattered with mud, a cluster of weary riders slogged

onto the makeshift pontoon bridge that linked Richmond with the south

bank of the James River. Out front, a gray-bearded officer rode

a drooping gray horse. His uniform was soaked through, and

rain spilled off his war-stained hat. Beneath it, his face was a

portrait of gloom. Yet he sat erect, head up. As he passed

by, some of those watching wept. Then he crossed the bridge

into the ashes of the Confederate capital. When people there saw

him coming, they crowded along his route and cheered him. Many

were blue-uniformed soldiers of the Union.

The day was April 15, 1865. Robert E. Lee was home from the war.

Federal troops and newly freed slaves had cleared

lanes through the rubble of downtown Richmond, burnt 12 nights earlier

when

Jefferson Davis and his government fled. Through the shambles,

Lee rode slowly uphill, repeatedly lifting his hat to answer

the cheers. Outside 707 East Franklin Street, the townhouse

where his ailing wife had spent the last years of the war, women,

children, and old men thronged to reach out and thank him. He

found it hard to speak. After shaking a few hands, he made a

little bow and backed inside. As he closed the door on the

Civil War, he entered into history, into legend, into what some

insist is mythology.

In less than three years at the head of the Army of

Northern Virginia, Lee’s generalship had produced stunning victories.

By any military standard, he was a hero, the unafraid underdog,

the most admired soldier of America’s fiery trial. His chivalrous

conduct toward friend and enemy, private and president had won

him loyalty at home and admiration abroad. After his surrender,

he set an example of manly acceptance for the defeated South.

Yet in this spring of 2000, nearly a century and a

half after he surrendered his army at Appomattox, Lee is again amid

conflict—of

words and symbols rather than arms. Though he spent far more of

his years in Alexandria and Arlington than in Richmond, the

current dispute is centered in the erstwhile Confederate

capital.

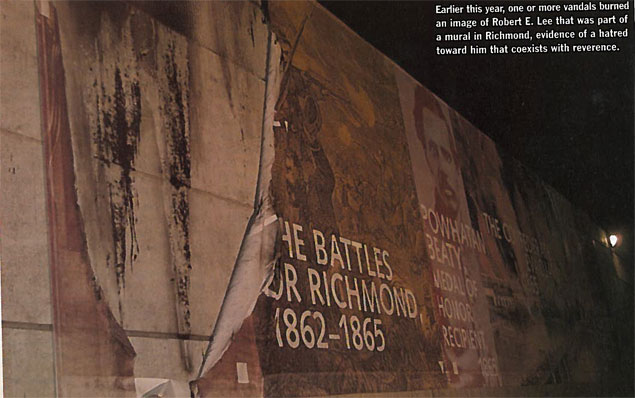

While revisionist historians dissect his record, some

aggrieved citizens protest the public presence of his picture there

in the city he fought to defend. After officials appeased

objectors by removing his uniformed likeness from a display depicting

Richmond’s long history, vandals defaced the image of Lee as

civilian that had been substituted. They can see Lee only in

black and white, as a symbol of the old South and slavery.

He was much more interesting than that.

Peace and reconstruction hardly had begun when

those still devoted to the lost cause of the Confederacy set out to

elevate

Lee to sainthood. They were not alone. As early as 1867, while

Lee was president of a struggling Virginia college, a New York

admirer wrote a children’s book that raised him to the heights

alongside Santa Claus. It tells how a Virginia girl who lived

near Appomattox witnessed Lee’s surrender. Rushing to him, she

cried, “Oh, General! Oh, General! Has it come to this?”

“The noble old man looked at her for a moment, while the big tears rolled down his care-worn cheek and said, ‘Be reconciled,

my child; the Supreme knows best.’”

The child who heard this story asked, “Did General Lee say that?” Assured that he had, she said, “Well, then, I will try to

say so too, for he is one of the noblest men God ever made. Bless his dear old heart!”

Three-fourths of a century later, the very name of Lee

still carried almost biblical significance among white Southerners,

from elderly ladies to schoolboys. I grew up in southside

Virginia, on Lee Street in Danville, and attended Lee Street Baptist

Church. I wasn’t surprised to hear about the boy who came home

from Sunday school and asked his mother whether General Lee

appeared in the Old Testament or the New. In the fifth grade,

at Robert E. Lee School on Loyal Street, I played Lee in our

Pageant of Virginia, wearing borrowed riding boots and

gauntlets that came up to my elbows. Our Virginia history textbook

was less imaginative than Robert E. Lee and Santa Claus, but it

had much the same tone of reverence.

More sophisticated authors and orators produced more sophisticated versions of what made Lee special.

Virginia-born Woodrow Wilson, ambitious to become

president, said, “We use the word ‘great’ indiscriminately,” for

tycoons,

writers, orators, heroes—“But we reserve the word ‘noble’

carefully for those whose greatness is not spent in their own interest.

. . . Now that was the characteristic of General Lee’s life.”

Former Union colonel Charles Francis Adams Jr.,

grandson and great-grandson of Yankee presidents, said years after the

war

that 20th-century America desperately needed someone like Lee

as its leader. A noted British military historian called Lee

“undoubtedly one of the greatest, if not the greatest, soldier

who ever spoke the English tongue.” As late as 1989, the Encyclopedia

Americana adopted that language as its own.

Many other soldiers—Rebels, Yankees, and

foreigners—agreed with those assessments. More books have been written

about Lee

than about any Civil War figure except Lincoln. Most have been

praiseful. But inevitably, such uncritical praise provoked

reaction.

Even before Lee took command outside Richmond in 1862,

there was press and political criticism of his soldiering. It grew

after the war, when politicians and ex-generals clashed over

credit and blame for what had happened. And today, Lee’s heroic

image makes him a target for the idol-smashing so fashionable

among historians, novelists, and moviemakers.

History is in the very soil of the Northern Neck,

the long peninsula between the Potomac and Rappahannock rivers. Three of

the nation’s first five presidents—George Washington, James

Madison, and James Monroe—were born on the Neck within 30 miles

of each other. The only brothers to sign the Declaration of

Independence—Richard Henry Lee and Francis Lightfoot Lee—were

born at Stratford Hall plantation, just down the Potomac from

Washington’s birthplace at Pope’s Creek.

Their family had been a force in Virginia for well

over a century when another Henry Lee won the nickname “Light-Horse

Harry”

as Washington’s favorite cavalryman. After the Revolution,

Harry married his cousin and became the master of Stratford Hall.

He rose in politics, serving three terms as governor. In

Congress, it was Lee who eulogized Washington as “first in war, first

in peace, and first in the hearts of his countrymen.”

During Harry’s political ascent, his first wife died

and he married Anne Hill Carter of Shirley plantation on the James,

bringing

together two of the state’s most illustrious families. Their

youngest son, Robert Edward, was born on January 19, 1807, at

Stratford plantation. His cradle is still there. But when

Robert was barely old enough to store away memories, he left Stratford.

Light-Horse Harry’s potential had seemed limitless,

but he speculated in land and fell into debtor’s prison. He lost

Stratford,

and Mrs. Lee had to take her family to Alexandria, where the

family lived successively on Cameron, Washington, and Oronoco

streets. Harry died in disgrace, leaving Robert fatherless at

11.

Thus, when Robert Lee decided to become a soldier, he

had a family name to live up to—and to live down. Light-Horse Harry’s

military reputation still gleamed bright enough to help his son

get an 1825 appointment to West Point. Four years later, he

graduated without a single demerit. Then he spent 17 years on

routine engineering assignments in the slow-moving “old army.”

Lee’s greatest satisfaction in that long stretch was

personal: In 1831, he married Mary Anne Randolph Custis,

great-grand-daughter

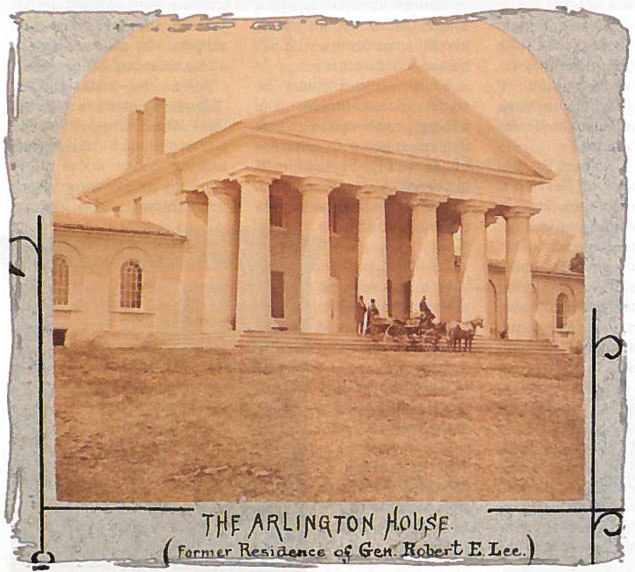

of Martha Washington. The Custis mansion at Arlington, across

the Potomac from the capital, was a virtual memorial to General

Washington.

For the next 30 years, Arlington was Lee’s home,

“where my affection and attachments are more strongly placed than at any

other place in the world.” Six of his seven children were born

there. This link strengthened Lee’s devotion to George Washington

as model for his own life. As one biographer wrote, “more than

ever had he now a reputation to live up to—the reputation of

Washington, and from this day onwards he became his

representative on earth.”

When Lee departed for the war in Mexico, he carried

Washington’s silver as part of his kit. There, as a 40-year-old captain,

he got his first lessons of combat under two very different

veterans of the War of 1812—generals Zachary Taylor and Winfield

Scott.

Taylor, “Old Rough and Ready,” was so indifferent to

military trappings that his own troops sometimes mistook him for a stray

farmer. But it was with Scott, “Old Fuss and Feathers,” that

Lee served first under fire and learned to operate on a command

level. Scott loved pomp and glitter but was a bold strategist

and serious student of war.

Campaigning toward Mexico City, Lee became the old general’s most trusted staff officer. Later, Scott would call him “the

very best soldier that I ever saw in the field.”

Skeptics of Lee’s character make much of his

thoughts and actions during the slavery debate that led to civil war. As

the

crisis rose in Washington, he was a cavalry colonel on the

southwest frontier. A strict soldier, he did not air his opinions

in public, but privately he agonized over events that were

tearing apart the country the Lees had served so long.

From Texas in late 1856, he wrote to his wife that

“Slavery as an institution is a moral & political evil in any

Country.”

At the same time, he deplored the “evil Course” of the

abolitionists. “How long [the slaves’] subjugation may be necessary

is known & ordered by a wise Merciful Providence. Their

emancipation will sooner result from the mild & melting influence

of Christianity than the storms & tempests of fiery

Controversy. . . . “

Lee happened to be on home leave in October 1859 when

an abolitionist band raided Harpers Ferry to incite a slave uprising.

President James Buchanan ordered him to put down the

insurrection. Lee’s force captured the raiders’ leader, John Brown, who

was tried and hanged. But Brown had ignited something that

would end in the death of hundreds of thousands and the liberation

of millions.

Back in Texas, Lee was against the cotton states’

threatening secession. He was devoted first to the land that had

produced

Washington and Light-Horse Harry—the father who said, “Virginia

is my country, her will I obey, however lamentable the fate

to which it may subject me.”

With the Deep South states pulling out, Robert Lee

wrote home that he could imagine no greater calamity than the breakup of

the Union. Still, “a Union that can only be maintained by

swords and bayonets, and in which strife and civil war are to take

the place of brotherly love and kindness, has no charm for me. .

. . If the Union is dissolved . . . I shall return to my

native State and share the miseries of my people, and save in

defence will draw my sword on none.” Later, he wrote, “I wish

for no other flag than ‘the Star spangled banner’ and no other

air than ‘Hail Columbia.’”

Thus he was deeply conflicted when he got orders to return east. As the crisis over Fort Sumter broke, General Scott, himself

a Virginian, called him into Washington.

There at the home of Montgomery Blair, across the avenue from the White House, Lee was offered command of the United States

Army. He refused and returned to Arlington.

Looking out across the city where the Washington

Monument and the Capitol dome still stood unfinished, Lee paced the

floor

from afternoon till past midnight. Only after the Virginia

convention voted to secede did he make the decision to resign from

the army that had been his life. To his sister, Lee explained,

“with all my devotion to the Union and the feeling of loyalty

and duty of an American citizen, I have not been able to make

up my mind to raise my hand against my relatives, my children,

my home.”

The next evening, a message from Virginia’s Governor John Letcher summoned Lee to Richmond.

He could not know when he left his beloved Arlington

that he would never set foot there again. He passed Fairfax, Manassas,

and Culpeper and crossed Bull Run, the Rappahannock and the

Rapidan, undistinguished towns and streams whose names would soon

burn into the nation’s history.

As the train clacked southward, he could rethink all

that had brought him to this trip of no return. Hundreds of other

professional

soldiers also had to choose, but few had historic associations,

family memories, or personal regrets so deep. Better than

most, Lee understood the enormity of the decision he had made.

Wearing a civilian suit, Lee stepped off the train at Richmond, not realizing that the protection of this city would soon

become the great mission of his life.

When Letcher asked him to be major general in command

of all Virginia’s forces, Lee agreed without hesitation. But the honor

did little to cheer him. Soon after, he was asked by Episcopal

Bishop Richard Hooker Wilmer whether he thought the war would

perpetuate slavery. “The future is in the hands of Providence,”

Lee said. “If the salves of the South were mine, I would surrender

them all without a struggle to avert the war.”

In those two sentences, the bishop heard Lee the

religious fatalist, who could lament war and slavery yet leave both in

the

hands of God, and Lee the traditionalist, who like Washington

believed that the soldier must stand apart from politics. A

British officer maintained that “his subservience [was] more

utter, more abject, than that of any other noted general to any

other Government in history.” Despite it, “what [his] bootless,

ragged, half-starved army accomplished is one of the miracles

of history.”

More than a year of war went by before the real Lee

emerged. In the spring of 1862, George B. McClellan brought his massive

Union army down the Chesapeake Bay to move on Richmond from the

east. Confederate general Joseph E. Johnston withdrew his

defenders mile by mile until he was wounded at the battle of

Seven Pines. Only then, with 100,000 invaders on Richmond’s doorstep,

did Jefferson Davis turn to Lee, who was 55 years old when he

took command of the Army of Northern Virginia.

By first ordering defensive earthworks around the capital, the new commander got nicknames like “Granny Lee” and “King of

Spades.” A young captain named E. Porter Alexander doubted whether Lee was bold enough to lead an army.

A colonel with the captain knew Lee better.

“Alexander,” he said, “if there is one man in either army . . . head and

shoulders

above every other in audacity, it is General Lee. His name

might be Audacity. He will take more desperate chances and take

them quicker than any other general in this country, North or

South, and you will live to see it, too.”

Within days, Alexander saw it. Lee threw his divisions

into a series of furious counterattacks, driving McClellan away.

Despite

grievous losses, he had saved Richmond. Never again would

soldiers wonder whether he was bold enough. The many Southern casualties

that poured into Richmond from those Seven Days battles

influenced rivals and some friends to argue later that he was too

bold.

After turning back McClellan, Lee expected that

Union army to join another advancing from Washington. He determined to

strike

first. Sending Stonewall Jackson on a sweeping flank march, he

brought up James Longstreet’s corps alongside, and together

they routed Union General John Pope at Second Manassas.

Reporting to Jefferson Davis, Lee said, “We mourn the

loss of our gallant dead in every conflict yet our gratitude to Almighty

God for his mercies rises higher and higher each day, to Him

and to the valour of our troops a nation’s gratitude is due.”

Thus he spoke after every victory, with never a hint of the

self-congratulation rife among many other generals—but with a

characteristic note of sanctimony, of assurance that he and not

the Yankees was doing God’s will.

To follow up this success, Lee took his army across

the Potomac into Maryland, confident that he could outmaneuver

McClellan.

But by pure luck, McClellan’s soldiers outside Frederick had

found a lost copy of Lee’s complex battle plan wrapped around

three cigars. McClellan moved to confront Lee along Antietam

Creek on September 17, 1862. Their armies surged back and forth

from early morning till near dusk. By the end of the day, more

than 23,000 soldiers on both sides were killed, wounded, or

missing, making it the bloodiest single day in American

history. Only Lee’s tactical skill and the bravery of his outnumbered

troops prevented disastrous defeat.

When that day was over, the Southern army was “worn

& fought to a perfect frazzle,” wrote artilleryman Alexander. He

added,

“No military genius, but only the commonest kind of common

sense” was needed to see that if McClellan had attacked all-out

the next day, he could have “destroyed [Lee] utterly.”

But McClellan did not. If the Union commander was

lucky to have found Lee’s order, Lee might seem luckier to have faced

McClellan

again instead of some less cautious general.

Lee created his own luck: Repeatedly, he gambled

against heavy odds, and his aggressiveness convinced opponents that he

was

stronger than he was. He understood that if he showed caution

more in keeping with his true numbers, the war would be short.

That December, looking on as his troops shredded Union

attackers at Fredericksburg, Lee said. “It is well that war is so

terrible;

else we should grow too fond of it.” He did not habitually

spout pronouncements suitable for framing, but his biographer believed

that sentence “revealed the whole man in a single brief

sentence”—the battle glow instinctive in Light-Horse Harry’s son,

tempered by the brooding understanding of how many men were

still to die.

Lee’s battlefield decisiveness created his “supreme

moment as a soldier” when he defeated “Fighting Joe” Hooker at

Chancellorsville.

In early May of 1863, Lee defied all textbook rules by dividing

his force and sending Stonewall Jackson far around Hooker’s

flank. In the vicious battle, Jackson was fatally wounded in

the moonlit thickets by his own men.

That battle was the summit of two historic military

careers, each lifted higher by the other. The mutual confidence between

Lee and Jackson inspired them to do things together that they

would not have dared with anyone else. The battle was won by

their teamwork, by the determination of their soldiers—and by

Lee’s reputation: The turning point came before the fight was

fully joined, when Hooker in his mind came face to face for the

first time with Lee, and he folded.

Lee’s aide, Major Charles Marshall, was with him as

bedraggled Confederate soldiers surged around their general, cheering

him in the burning woods. Marshall wrote, “As I looked upon

him, in the complete fruition of the success which his genius,

courage, and confidence in his army had won, I thought that it

must have been from such a scene that men in ancient times

rose to the dignity of gods.”

Historians playing psychiatrist suggest that Lee was

so tightly repressed beneath his austerity that in combat his inner self

burst loose and drove him to attack against all reason. But

that implies lack of control, something that even Lee’s critics

rarely perceive. Their most telling example came after the

Confederate high point at Chancellorsville, when Lee launched his

last major invasion of the North.

When his troops bumped into Federals outside the town

of Gettysburg, Lee had no Jackson at his right hand. But he still had

the troops who had fought so magnificently two months earlier.

As he wrote after Chancellorsville, “There never were such

men in an army before. They will go anywhere and do anything if

properly led. . . . “ After two days of pounding, Lee sent

those troops across the open fields in the attack that history

remembers as Pickett’s Charge.

Two of my great-grandfathers were in that charge,

in the 53rd Virginia and the 7th North Carolina. More than once I have

stood

on Seminary Ridge where they spread out before moving across

those summer fields and tried to feel what they must have felt,

seeing the mass of Union battle flags waiting for them behind

the stone wall on Cemetery Ridge, watching the Union cannon

line up hub to hub, waiting. I have knelt behind that wall and

looked back the other way, wanting to see what the Yankees

saw as my grandfathers and 15,000 other Confederates kept on

coming as solid shot and canister tore holes in their long ranks

of gray. I have never been able to do it with dry eyes.

Lee’s critics asserted that on that July afternoon his

army had not been “properly led,” that he should not have attacked

there and then—and hindsight supports them. His assault was

opposed by his balky and argumentative corps commander, James

Longstreet, and then imperfectly coordinated. On the heels of

his grandest victory, Lee’s army was repulsed in the climactic

battle of the war.

He accepted the defeat as his own. To George Pickett,

mourning his division, Lee said, “Come, General Pickett . . . upon my

shoulders rests the blame. The men and officers of your command

have written the name of Virginia as high today as it has

ever been written before. . . . Your men have done all that men

could do; the fault is entirely my own.”

Through July 4, the whole next day, Lee kept his

command in place, organizing his retreat but seeming to glare across at

Union

Major General George G. Meade, daring him to renew the fight.

Even then, Meade refused to follow up with an attack that could

have demolished the Rebel army. The Confederates limped back to

Virginia.

Once again, Lee’s reputation for aggressiveness had

protected his army. But the next spring, Lincoln sent against him a

general

who saw the hard truth beyond that reputation: After three

years of war, Lee had no prospect of replacing his losses. And

he was hobbled strategically by his mission of protecting

Richmond.

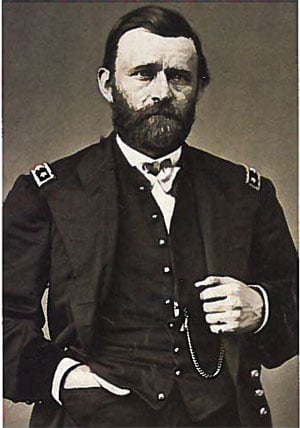

When Ulysses S. Grant came east to take command of Union forces, he understood that Lee’s army, not the Confederate capital,

was his main objective—but the way to get at that army was to drive on to Richmond and pin Lee down in siege warfare.

Grant had little in common with Lee beyond a West

Point education and a high order of generalship. He was short, often

unkempt

in a private’s coat, wholly without the aura of dignity that

surrounded Lee even in midbattle. He chewed cigars, and sometimes

he drank. But he had a decisive mind, a stubborn will, and a

strategy.

When Grant started to carry it out in May 1864, Lee

made him pay a terrible price at the battles of the Wilderness and

Spotsylvania

Court House, near Fredericksburg. In the thickets, Lee had to

be restrained from personally leading troops in a desperate

charge. An anonymous poem told of it:

“There he stood, the grand old hero, great Virginia’s

god-like son/Second unto none in glory—equal of her Washington.” Texas

troops around him refused to go forward until he moved out of

harm’s way; one of them grabbed his horse’s reins. As he watched

them charge, his “god-like calm was shaken, which no battle

shock could move/By this true, spontaneous token of his soldiers’

child-like love.”

Lee’s troops, and poets afterward, may have seen him

as “god-like,” but Grant did not. Instead of pulling back after each

mauling as his predecessors had done, Grant drove on. In a

month, he lost almost 55,000 troops in a campaign that ground down

in the bloodbath of Cold Harbor, outside Richmond.

From there, Grant sideslipped south of the James River and Petersburg. That began the siege of Richmond—and as Lee himself

had said, once that happened, loss of the capital was only a matter of time.

During that last hard winter of war, too late to

change anything, Lee was made general in chief of all Confederate

forces.

In Richmond to plead for more supplies, he told his oldest son,

“Well, Mr. Custis, I have been up to see the Congress, and

they do not seem to be able to do anything except to eat

peanuts and chew tobacco, while my army is starving. . . . When this

war began I was opposed to it, bitterly opposed to it, and I

told these people that unless every man should do his whole duty,

they would repent it—and now, they will repent.”

After Lee’s final effort to break out of the

tightening noose, his thin lines were turned at last. On April 2, 1865,

he telegraphed

Jefferson Davis that Richmond must be evacuated. Retreating

westward, Lee groaned to Brigadier General Henry A. Wise over

what was happening to his country. Wise told him, “There has

been no country, General, for a year or more. You are the country

to these men. They have fought for you.”

Two days later, at the obscure village named Appomattox Court House, Grant’s divisions caught up with the disintegrating Army

of Northern Virginia.

From Grant came a note asking Lee to surrender, to prevent “any further effusion of blood.”

Lee at first refused. Then he learned that the Yankees

had circled ahead and cut off further flight. Hearing this, Lee said

to his aides, “Then there is nothing left for me to do but to

go and see General Grant, and I would rather die a thousand

deaths.”

The way Lee surrendered the last remnant of his army has contributed as much to his legend as has the way he fought the war.

Porter Alexander urged him to let his soldiers

scatter, perhaps to fight on as guerrillas. Lee said no; they would

become

marauders, stealing to survive, bringing on “a state of affairs

it would take the country years to recover from.” Alexander

wrote later: “He had answered my suggestion from a plane so far

above it, that I was ashamed of having made it.”

On April 9, Lee put on his best uniform, with a red

sash and engraved sword. “I have probably to be General Grant’s prisoner

and thought I must make my best appearance,” he said as he rode

toward the front before dawn on that Palm Sunday morning.

Lee met Grant at the home of a Virginian who had moved

away from Manassas to escape the war. Grant, whose toughness in the

West had won him the nickname “Unconditional Surrender,” was

generous at the end. He allowed Southern soldiers to take their

horses home for the spring plowing. At Lee’s request he ordered

rations for the famished Confederates.

Lee returned to his troops. Some were burning their

ragged battle flags rather than surrender them. They crowded to the

roadside

and reached out to touch his horse’s flanks as he rode past.

Some started to cheer him, then broke down in sobs. One held

up his arms and shouted, “I love you just as well as ever,

General Lee!” Tears welled in Lee’s eyes, the first those close

to him could remember seeing.

Last April, I walked again over that most hallowed

American ground, when the apple trees bloomed as they did that Sunday in

1865. I wondered what Lee must have been thinking. How far had

these men and boys marched while he rode, day after day, battle

after battle? How many others would still be living, at home in

peace, if he had not held them together fighting for so long?

How many hundreds of thousands of widows and fatherless

children, on both sides, wished now that he and those who followed

his lead had stood by the Stars and Stripes in 1861?

Lee dismounted, beside a great oak where he would tent

for the night, and turned about. “Men,” he said, “we have fought

through

the war together; I have done the best I could for you. . . .

Go home now, and if you make as good citizens as you have soldiers,

you will do well, and I will always be proud of you. Goodbye,

and God bless you.”

His throat was so full he could say no more.

The next morning, he and Grant had a quiet

conversation on a little knoll between the armies. Grant suggested that

no one

had greater influence in the Confederacy than Lee and that if

Lee advised surrender everywhere, others would comply. But Lee

said he could do no such thing without consulting President

Jefferson Davis.

Grant backed off: “I knew there was no use to urge him to do anything against his ideas of what was right.”

Lee’s chief of staff drafted for him an order to the

army. Lee struck out a paragraph that “would tend to keep alive the

feeling

existing between North and South.” Then he signed his final

order, which ended, “With an increasing admiration of your constancy

and devotion to your country, and a grateful remembrance of

your kind and generous consideration of myself, I bid you an

affectionate

farewell.”

Union officers, friends from before the war, came to

shake his hand. In his tent, he dined on Confederate rations captured

by Federal cavalry, now reissued. Outside, a band played

“Parting Is Pain,” whose words say, “Now the Battle din is o’er.

. . . Useless now, our good swords lie. . . . “

Lee did not want to leave his troops, but he could not

bear to watch their formal surrender, when they marched past their

former enemies to stack arms for the last time. On April 12,

with his closest aides, he started back to Richmond in the rain.

Aside from bearing the weight of his leadership

role, Lee had suffered as much as most ordinary Southerners in the war.

His

home at Arlington was seized, its grounds turned into a Union

graveyard and a camp for thousands of freed slaves. One of his

daughters died of typhoid fever. One of his sons, the cavalry

general “Rooney,” was wounded at Brandy Station in 1863, then

captured and held prisoner for nine months.

Rooney’s plantation was occupied and ruined. The

oldest son, Custis, was captured in the war’s final week. The youngest,

Rob,

had fought as an enlisted artilleryman. Lee’s refugee wife,

crippled by arthritis, was threatened by Richmond’s evacuation

fire, then protected by Yankee soldiers.

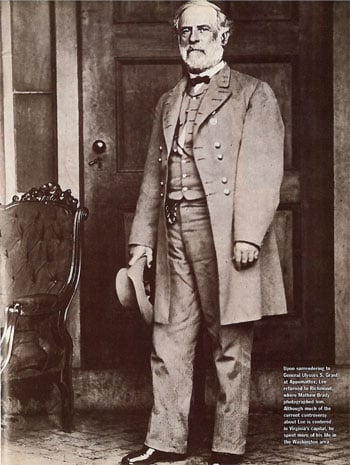

A few days after Lee returned, the Northern

photographer Mathew Brady persuaded him to pose at the rear of the house

on Franklin

Street. In that likeness, Lee is tired, sunburned, dignified,

but his eyes still show a glint of defiance. He seems older

than his 58 years.

Lee the lifelong soldier did not know after Appomattox

how he would support himself and his family. Richmond friends sent

them bread, milk, and fruit. Lee turned down every invitation

to prosper by his name—to be president of the Chesapeake & Ohio

Railway; to command the Romanian army; to be governor of

Virginia; to write his memoirs—or merely sign them written by someone

else; to be president of insurance companies; to move into an

English manor house with an annual stipend.

That summer he accepted the presidency of tiny

Washington College in Lexington. There, at a school endowed by President

Washington

a lifetime earlier, he could help rebuild the Southern youth

that had been sacrificed to the lost cause. His annual salary

would be $ 1,500. James Branch Cabell, a Virginia author noted

for his blistering sarcasm toward others, wrote that “in a

life over-brimming with magnanimities, this was [Lee’s] most

heroic action.”

Controversy over war and reconstruction flared north

and south, but Lee stayed out of it, urging his former soldiers to be

good citizens of the reunited country. To General P.G.T.

Beauregard, he wrote, “I need not tell you that true patriotism

sometimes

requires of men to act exactly contrary at one period to that

which it does at another, and the motive which impels them,

the desire to do right, is precisely the same. The

circumstances which govern their actions change, and their conduct must

conform to the new order of things.”

On an evening near the end of September 1870, Lee sat late at a vestrymen’s meeting in Lexington’s Grace Church. His last

gesture there was offering $ 55 of his own funds to raise the minister’s salary.

Then he walked home in a cold rain. When he opened his

mouth to say grace at the dinner table, no sound came. He had suffered

a stroke, and for two weeks the town and the South prayed for

his recovery. In his delirium, Lee thought he was back in the

field. He called for General A.P. Hill to move up. He talked

on, in and out of sleep. On the morning of October 12, he said

quietly, “Strike the tent,” and breathed his last.

He departed without writing the history of his army,

which he had wanted to memorialize his brave soldiers. Others wrote

their

history, and his own. His admirers renamed the college

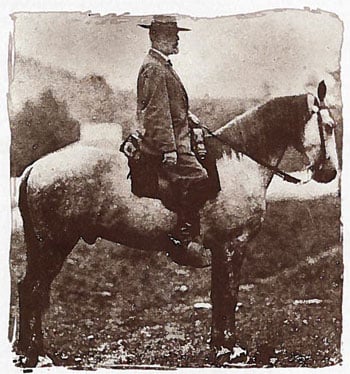

Washington and Lee and still pay respect to his tomb there. For more

than 60 years, the skeleton of his horse Traveller stood

alongside.

Why this reverence for Lee persists, when our

country has produced so many other great generals whose wars ended in

victory,

would be no mystery to those who knew him. After his death,

they found in his military valise a scrap of paper on which he

had copied a passage that defines a gentleman. Whether he

originated those words or ever repeated them to his students in

his five years in Lexington is not known. But they clearly

speak for him.

They say that a man is set apart by how he uses “the

power which the strong have over the weak . . . the educated over the

unlettered. . . . The forbearing or inoffensive use of this

power or authority, or a total abstinence from it when the case

admits it, will show the gentleman in a plain light. . . . He

can not only forgive, he can forget; and he strives for that

nobleness and mildness of character which impart sufficient

strength to let the past be but the past. A true man of honor

feels humbled himself when he cannot help humbling others.”

In Richmond, Lee’s equestrian memorial has towered

above Monument Avenue for more than a century. Perhaps it will be the

next

target of those who vandalized his picture. But it is not

marble or bronze that most provokes contrarians who want to diminish

Lee’s place in history. Their inspiration is the monumental

biography by a man who was said to salute Lee’s statue on his

way to work each morning—Richmond newspaper editor Douglas

Southall Freeman.

In four volumes published in the 1930s, Freeman

painstakingly detailed Lee’s life—and minimized his missteps. Freeman’s

index,

for example, lists Lee’s personal characteristics, from

Abstemiousness and Amiability through Good Looks and Humility to Thrift

and Wisdom; of the 150 qualities listed, barely 10 could be

construed as negative. That work won the Pulitzer Prize and has

influenced everything written about Lee since—and more than any

other honor paid the general, it has driven the search for

faults in his image.

During the early years of civil-rights strife, I

worked at the News Leader, which had been Freeman’s newspaper. I didn’t

stay

long; I felt that in Richmond, admiration of Lee and his

soldiers was too often equated with segregationist politics and a

past that was gone forever. They are not the same thing.

The fever of those years has eased only to rise again,

stirred by the flaunting of the Confederate colors. Today’s

intentionally

provocative flag wavers do not understand Lee any better than

those who defaced his picture. Most Americans who do know him,

in the South and in the nation, see him as a historic figure,

as a decent man and brilliant soldier, rather than as a figurehead

for those who would turn back the clock.

Researchers discover individual letters, sometimes

sentences within letters, that they cite to challenge that version. A

reviewer

of one of my books wrote that “Lee’s mental and moral confusion

made him a bloodstained traitor, one who did more damage to

his country than any other in the history of the United

States.” Other critics say he was not really against slavery, and

therefore his decision to go with Virginia in 1861 was not as

painful as some who venerated him insisted.

Legally, Lee and hundreds of thousands of others may

indeed have been traitors. Whether that was true morally, under the

circumstances

of their time, apparently will be debated forever. And Lee

certainly was no abolitionist. The bulk of his writing makes clear

that though he deplored slavery, he saw no better way at hand

and left the matter for God to settle. Remember that as late

as 1862 Abraham Lincoln, soon to become the Great Emancipator,

said that if he could save the Union while keeping slavery,

he would. Like so many lesser men, Lincoln and Lee were

complicated, pulled different ways on different days by roots, duty,

conscience, politics, strategy, all the tides of their time.

The chief finding of military analysts against Lee is

that he was too aggressive, which cost the South thousands of lives.

They say the Confederacy could have fought on much longer if he

had stood more often on the defensive, as he did at Fredericksburg.

But his pugnacity had made him seem dangerous, even when his

army was crippled. Otherwise, McClellan after Antietam or Meade

after Gettysburg might well have crushed his army and shortened

the war by many months. In posterity as in battle, Lee’s main

contender for honors was Grant—yet there was no bloodier

example of unwise attack than Grant’s 1864 assault on Lee’s lines

at Cold Harbor. Both commanders were superb generals. Neither

was perfect.

The idea of Lee as godlike hero is what rival generals

resented and revisionist historians challenge today. As one who

borrowed

boots to pretend to be Lee when I was ten, who as student,

infantryman, and writer has imagined walking with him for many

years since, I consider their criticisms a needed antidote to

the legend of his perfection. Those diligently discovered flaws

round out the whole truth of Lee’s stature as man and as

soldier. He had flaws because he was not a god but a complex human

being, torn within himself as tragically as the families whose

sons separated to fight for North and South—caught with his

country in the pivotal moment of American history.

Ernest B. “Pat” Furgurson is the author of several books on the Civil War, including Chancellorsville 1863: The Souls of the Brave and Freedom Rising: Washington in the Civil War.

This story appeared in the April 2000 issue of The Washingtonian.