The grandness of Ruth Bader Ginsburg’s chambers makes the

Supreme Court justice appear even smaller than usual.

Rich wood paneling reaches from the floor to the ceiling. A massive desk anchors the space. The air is heavy with floral perfume. The justice wears an elegant black knit dress, her hair pulled back in her signature style.

Ginsburg moved to these chambers in 2009, and newly confirmed

justice Sonia Sotomayor took over her former space. The occasion was a

happy one for Ginsburg, not only because of the office upgrade but because

she had long hoped for more women to join her on the high-court bench.

Ginsburg had been the sole woman since Sandra Day O’Connor’s retirement in

2006.

Including the court’s newest member, Elena Kagan, Ginsburg is

now one of three female justices—just one of many things that have changed

since President Bill Clinton nominated her to the Supreme Court in 1993.

During her nearly 20 years there, she has been a stalwart of the court’s

liberal wing and a pioneer for women jurists. She has survived cancer

twice and coped with the death of her husband, Martin

Ginsburg.

But there has been one constant. The now 79-year-old Ginsburg

is surrounded by art, as she has been since childhood. A small Bose stereo

fills her chambers with opera music—one of her lifelong loves and an

appropriate soundtrack for such a regal setting. Her walls boast works on

loan from the Smithsonian, including two original Rothkos, a painting by

Max Weber, and one by Josef Albers. (Another Albers painting, which

usually hangs in her chambers, is currently part of a traveling exhibit.

Ginsburg vows that she won’t retire until it returns.) Her shelves hold

photographs of her with local theater icons such as Shakespeare Theatre

Company artistic director Michael Kahn and opera stars from Mirella Freni

to Denyce Graves.

Ginsburg speaks so softly that she can be difficult to hear.

She chooses her words carefully, allowing long silences to pass before

offering her next thought. But when talking about art—whether visual,

theater, or opera—she smiles often and easily recalls decades-old memories

of plays and concerts.

Art, says Ginsburg, “makes life beautiful.”

Growing up in Brooklyn, Ruth Bader began playing the piano at

age eight and the cello in high school; she never progressed beyond the

last row of cellists, but that was fine with her: “I just wanted to be in

the orchestra.”

Her mother introduced her to theater at the nation’s oldest

performing-arts center, the Brooklyn Academy of Music—as Ginsburg

remembers it, “my dream place as a child.” The academy held children’s

performances on Saturdays, and Ginsburg’s mother, Celia, bought a

subscription to all of the shows. She would take Ruth and her cousin, who

lived with them for a time, every weekend.

“I remember Mrs. Wiggs of the Cabbage Patch—that was

one of my favorite plays,” says Ginsburg.

She saw her first Laurence Olivier film, Henry V, at

the academy. The experience stuck with her, though it wasn’t until high

school that she developed a serious interest in Shakespeare, when her

English class read Hamlet. Afterward, the class took a field trip

to see the movie version, also starring Olivier.

In Washington, Ginsburg is a regular on opening night of

Shakespeare Theatre Company productions. The theater has documented her

attendance at 28 shows, but she has been to many more. She frequents other

Washington theaters, too. Arena Stage reports that Ginsburg has attended

42 of its shows since 1999.

And she doesn’t let the weight of her job distract her. “Her

posture is not what it used to be—she hunches over a little bit,” says Ed

Zakreski, chief development officer of Shakespeare Theatre Company. “I

think you could look at her during a performance and think she’s not

paying attention. But she doesn’t miss a word.”

Ginsburg is such a familiar presence at Shakespeare Theatre

that artistic director Michael Kahn refers to her simply as Ruth. The

justice often joins Kahn at pre-show dinners held at the theater on

opening night. She also occasionally writes him letters giving feedback on

performances. Once, over dinner, Kahn pointed out that while Ginsburg had

seen much of his work, he had never seen any of hers.

“So she invited me to the court for a pretty important case,

and she said, ‘We’ll have lunch later,’ ” Kahn recalls. “I only wished my

mother was alive so I could tell her.”

The two ate in the justices’ dining room, and Kahn says he was

“flabbergasted” that nearly all of the justices attended—Antonin Scalia

was the only one missing. “They asked me lots of questions about how I got

started and what the theater is like.”

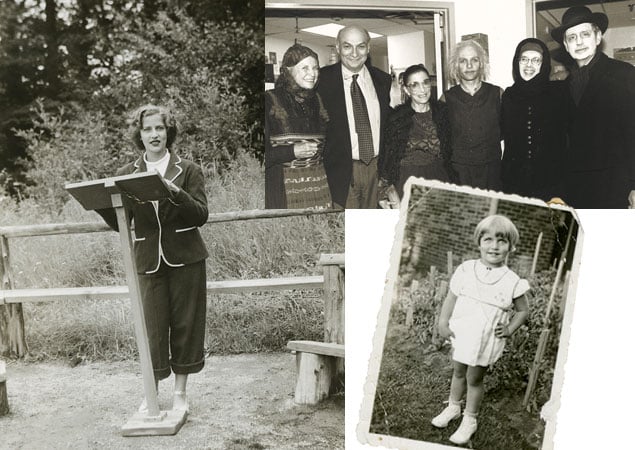

In her chambers, Ginsburg stands after a while to explain some

of the photos on her shelves. Her involvement with Shakespeare Theatre

Company goes beyond attending plays. She has appeared on its stages many

times—and has pictures to prove it.

The theater used to have a tradition of allowing high-profile

jurists to appear in minor roles for one night—lawyers’ night—during a

show’s run. Ginsburg gestures to a picture of herself in a troll costume

sporting a long tail. She’s flanked by Justice Stephen Breyer, now-retired

justice Sandra Day O’Connor, and DC federal judge Gladys Kessler. The

photo was taken during the 1998 production of Peer Gynt. Ginsburg

says it was her husband’s idea that she play a troll.

She reaches for another photo, this one taken during Henry

VI. Ginsburg requested the role of the butcher because she wanted to

say this famous line: “The first thing we do, let’s kill all the

lawyers.”

“I asked Michael Kahn if I could ad-lib,” Ginsburg says,

smiling. The line she added? “Then the reporters.”

When Ginsburg was 11, her aunt took her to her first opera.

Dean Dixon, a conductor who became known for putting on children’s

concerts, was conducting an abbreviated version of the opera La

Gioconda by Ponchielli. Between songs, Dixon explained the

plot.

“I was fascinated by this,” says Ginsburg. “It was just this

very dramatic story and this gorgeous music.”

Ginsburg says Dixon, who died in 1976, never got the respect he

deserved: “He was African-American at a time when African-Americans were

not conductors. One of the things he said was that in all of his

conducting, no one ever called him maestro.”

Throughout high school, Ginsburg made frequent trips to

Manhattan to see operas at the New York City Center, where she would sit

in the last row of the highest balcony. When 21-year-old Ruth Bader

married young Army lieutenant Martin Ginsburg in 1954, opera became a

shared passion.

Shortly after their wedding, Martin was assigned to the Army

base in Fort Sill, Oklahoma. Even far removed from the cultural mecca of

New York, the couple found ways to integrate opera into their life. They

would check out records from the base’s library. The Metropolitan Opera

traveled in those days, and when the tour stopped at the Dallas

fairgrounds, the Ginsburgs would make the nearly four-hour trip to see

it.

The couple returned to New York in 1958, after Martin graduated

from Harvard Law and landed a job at the Manhattan firm Weil, Gotshal

& Manges. Ruth, who was a year behind her husband in law school,

transferred from Harvard to Columbia. Their daughter, Jane, was three at

the time.

Ginsburg had been one of just nine women in her class of more

than 500 at Harvard, and after her second year of law school, she was the

only woman offered a summer-associate position at the prestigious firm

Paul, Weiss, Rifkind, Wharton & Garrison in New York. (The firm

infamously declined to hire her after she graduated.) Ginsburg was a

trailblazer, but that didn’t stop her from feeling guilty about spending

time away from her child.

To compensate for the hours she devoted to studying and

working, says Ginsburg, “every Saturday and Sunday, we went to something

culturally enriching.”

When Jane—now a law professor at Columbia—was four, Ginsburg

took her to her first opera. “This four-year-old stands up, and she

screams at the top of her lungs. That’s what the soprano sounded like to

her,” says Ginsburg. “So I quickly ushered her out. I said, ‘Maybe I’m

overdoing this.’ ”

By the time Ginsburg’s son, James, was born 10½ years after

Jane, Ginsburg had relaxed considerably in her parenting. But James had a

natural affinity for classical music.

“This child who was, I’d say lively—his teachers would say

hyperactive—for music, was at rapt attention,” Ginsburg remembers. She

began taking him to see the Little Orchestra Society at Hunter College

and, when he was older, the New York Philharmonic.

Today James Ginsburg is founder and president of Cedille

Records, a classical-music label in Chicago. He’s married to soprano

Patrice Michaels.

Justice Ginsburg doesn’t take any credit for developing her

son’s love of music: “I think it’s just innate.”

Martin and Ruth Ginsburg moved to Washington in 1980, when

President Jimmy Carter appointed her to the federal court of appeals for

the DC Circuit. Martin became a tax-law professor at Georgetown and joined

the law firm Fried, Frank, Harris, Shriver & Jacobson. They lived at

the Watergate and would often walk to the Phillips Collection.

The couple’s love of art was evident in their home.

“There was always wonderful music playing,” says Dori

Bernstein, who was both a colleague of Martin Ginsburg’s at Georgetown and

a clerk for Ruth Ginsburg when she was an appellate judge. “There was a

beautiful piano in their apartment. It was just a place filled with

beauty. You could see that was an important part of their

lives.”

Martin Ginsburg died of complications from metastatic cancer in

2010, days after the couple’s 56th anniversary. Justice Ginsburg arranged

a celebration of his life replete with music. Opera star Denyce Graves was

among the performers.

Even without Marty by her side, Ginsburg still attends nearly

every production of the Washington National Opera.

Says the opera’s president, James Feldman: “We do consider her,

informally, part of the family.”

Though lawyers’ night at Shakespeare Theatre Company is a thing

of the past, Ginsburg graced the stage of the theater’s Sidney Harman Hall

this past April for its annual mock trial.

In Washington, home to some 80,000 lawyers, the mock trial is a

popular event. Each year a legal issue from a classic play is turned into

a fictional court case. A panel of real judges listens as two of the

city’s high-profile attorneys duke it out before an audience. For the past

seven years, Ginsburg has served as the presiding judge.

This year the event featured the divorce proceedings of Count

Claudio and Lady Hero from Shakespeare’s Much Ado About Nothing.

Ginsburg peppered the attorneys—Washington divorce lawyer Sanford Ain

represented Hero, and white-collar criminal defender Reid Weingarten

advocated for Claudio—with questions that only someone well versed in the

play’s complicated plot would think to ask.

Her sense of humor was on full display. After Weingarten

described Lady Hero as manipulative and duplicitous, Ginsburg suggested

that Hero sounded like “a ripe candidate for the study of

law.”

The event came just a month after Ginsburg and her fellow

justices had heard three days of oral arguments on the constitutionality

of President Obama’s health-care-reform law.

“It’s good to do something where I’m not thinking about this,”

she says, referring to the work that surrounds her in her chambers,

“because I go to sleep thinking about the issues at the

court.”

And though her Albers painting isn’t due back anytime soon,

it’s likely that art will remain part of Ginsburg’s life even beyond the

court. For the Supreme Court justice, that means every day will have some

beauty in it.

Shortly after writing this article, staff writer Marisa Kashino spotted Ginsburg at a performance of “The Normal Heart” at Arena Stage.

This article appears in the October 2012 issue of The Washingtonian.