It was the back yard that sold Christine Dieterich on the yellow brick Cape Cod on Glenbrook Road. She fell in love with the terraced gardens, pictured her children racing around outside and traversing the little bridge across a creek into the woods.

“It seemed idyllic,” Dieterich says.

She and her husband, Rogerio Zandamela, paid $1.5 million for the six-bedroom house in Spring Valley, an affluent neighborhood nestled in the far northwest corner of DC. They moved in in 2009.

Then one afternoon in late March 2010, Dieterich rounded the corner onto Glenbrook on her way home from work and found the street blocked by TV news trucks, cameras, and reporters. Army engineers excavating a yard across from hers had unearthed a rusty metal drum seven feet down that held a cache of glass bottles. Workers had noticed the ground smoking around the drum. White vapor was escaping from one of the bottles inside. They sealed off the site and tested the contents of the bottles.

“We found out the white vapor was arsenic trichloride,” Dieterich says. “That was our first piece of bad news.”

Arsenic-trichloride vapors can be lethal when inhaled. The Army Corps of Engineers, which was in charge of the dig, knew there might be toxic chemicals in the ground, but it wasn’t prepared for arsenic trichloride.

Neither was Christine Dieterich.

She knew that the campus of American University, just a block away, had been the site of chemical-weapons testing from 1917 to 1920. But the Army Corps had sent her a letter explaining the history and its current cleanup project. It said her property was safe.

What the Army failed to state explicitly was that Dieterich and her neighbors were living yards away from the first military Superfund site in a residential urban area, where the Army is actively searching for bombs and poisonous chemicals.

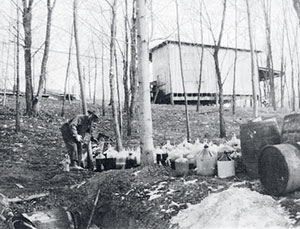

The Corps has been trying for years to pinpoint the location of a waste pit pictured in a grainy 1918 photograph. Sergeant Charles Maurer, shown standing over the pit, wrote on the back: “The most feared and respected place on the grounds. The bottles are full of mustard, to be destroyed here. In Death Valley. The hole called Hades.”

The Corps now believes that it has found “the hole called Hades”—directly across the street from Christine Dieterich’s home.

This past November, she watched from her kitchen as Army contractors tore down the three-story brick house at 4825 Glenbrook. The Corps will spend an estimated $12 million to excavate and restore the site. The dig could last into 2014.

“We are anticipating we will find additional lewisite in the soil under the house,” Army Corps project manager Brenda Barber says. Lewisite, made with arsenic, was perhaps the most toxic of the poisons tested on the AU campus. It was called “the dew of death” because a single drop could be lethal. Bombs with lewisite were on their way to Europe when World War I ended.

Dieterich has two children, ages five and one. She asked the Army to relocate her family until the digging was done, but her request was denied. “The Army assured us it would take care of my family if we were in harm’s way,” she says. “I should have asked more questions.”

The Corps has told Dieterich and her neighbors that its elaborate tenting system will protect them from any poisons. It plans to set up sensors that will trigger sirens if poison gases escape into the air.

“How can they expect me to have peace of mind and have my children play in the front yard while they are digging for chemical-warfare agents 20 feet away?” she asks. “I wake up at 3 am in a cold sweat. My children won’t be safe in their own home.”

• • •

With its tall trees and stately homes—which sell for upward of $4 million—Spring Valley is one of DC’s most prestigious neighborhoods. Richard Nixon, Lyndon Johnson, and George H.W. Bush all lived there. Attorney General Eric Holder makes his home there now, as do TV anchor Jim Vance and attorney Brendan Sullivan.

But in 1918, when the US was fighting in the trenches of Europe, Spring Valley was fields and farms. American University, atop the hill at Ward Circle, was a small, struggling college. The military, facing chemical weapons for the first time, leased property from the university to establish labs and testing sites. It summoned more than 1,000 chemical-weapons researchers to mix poisons and test the substances’ killing potential at the American University Experimental Station. They lobbed mortars from the edge of AU down toward what’s now Dalecarlia Reservoir.

In 1920, two years after the armistice, the government closed down the project but didn’t clean up the land. Soldiers dug pits just beyond the edge of the campus and buried artillery shells and glass jugs full of lethal compounds. According to the Corps, they didn’t keep records of the disposals.

From the 1920s on, developers bought up the property, carved roads, and built homes. The Army and American University kept the neighborhood’s toxic past secret. It wasn’t until 1993—when workers digging a utility trench not far from Dieterich’s home struck bombs—that Spring Valley’s chemical-warfare history became public.

Since then, the Army Corps has spent $221 million to clean up what it calls the Spring Valley Formerly Used Defense Site. The project has been the subject of hearings before Congress and the DC Council. Having found arsenic in the ground, the Corps has carted away thousands of tons of soil, and it’s still testing for more toxic waste. The Corps has drilled 53 wells in Spring Valley and found arsenic as well as perchlorate, a component of rocket fuel, in the ground water.

• • •

Twenty years after the first bombs were found, what do we know?

It’s clear that contamination is not widespread over Spring Valley’s entire 660 acres. The majority of homes in the neighborhood haven’t been affected by the chemical testing, and the Army has removed contaminated soil at many others. Real-estate values have remained strong. Most residents would prefer that Spring Valley’s toxic past recede, but it remains immediate and relevant.

Using archival maps and satellite images, historical records, geophysical probes, and ground-penetrating radar, the Corps has identified specific waste pits, testing trenches, and pathways from the firing range. It has dug up more than 1,000 munitions, most empty, some still intact with toxic agents. It has destroyed hundreds of munitions in a detonation chamber on federal property between Sibley Hospital and Dalecarlia Reservoir.

Have the buried poisons made Spring Valley residents sick?

Two surveys of the entire neighborhood have found no elevated incidence of cancers. But because the contamination affected specific streets and groups of houses built over known trenches and dumps, many residents believe that surveys encompassing all of Spring Valley are too diffuse and not conclusive.

“We need an independent assessment by the National Academy of Sciences,” says Nan Wells, a biologist who represents Spring Valley on the Advisory Neighborhood Commission. “It’s important that we have experts review the studies.”

Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health is close to finishing a survey, but it’s using entire Zip codes to compare the health of Spring Valley residents with that of Chevy Chase DC residents.

“We are not going to have any definitive information on actual cases,” says Mary Fox, the survey’s principal investigator. “We understand the frustration of the Spring Valley community. We are not going to be able to give them all the answers they are looking for.”

The best attempt at providing answers came from a 2004 survey of a 345-house “epicenter” of Spring Valley by Charles Bermpohl, a staff writer for the Northwest Current, a weekly paper that covers Spring Valley. Bermpohl found 160 cases of “chronic, often life-threatening and rare diseases.”

Bermpohl’s research found an alarming number of diseases, but experts have criticized the findings as anecdotal and unscientific. Bailus Walker, professor of environmental and occupational medicine and toxicology at Howard University, chaired a panel that studied Spring Valley for the District. “One of the most difficult things we faced was trying to determine if there were health effects, who was exposed, to what chemicals, how much, and for how long,” says Walker. “We were never able to get a handle on that. We did not see a cluster of cancers of the same organ system in the community.”

Kent Slowinski, an activist and Advisory Neighborhood Commissioner who worked with Bermpohl, says the research is “just the tip of the iceberg. It warrants further investigation.”

Two things have become clear in the 20 years of testing and turmoil: It’s nearly impossible to prove a direct connection between the toxic chemicals and a specific disease. And the laws are stacked against residents who attempt to use the legal system as a recourse, especially when the government is charged with creating the pollution.

Ask Camille Saum, who grew up on Sedgwick Street. She has been diagnosed with pernicious anemia—a rare and debilitating blood disorder—kidney disease, and lupus. She believes all of these conditions were triggered by an immune system weakened by toxic chemicals such as arsenic. She sued the Army to no avail.

“I don’t think the government treated me or anyone else well,” says Saum. “Look at all the people who died. I’m one of the lucky ones. At least I am alive.”

Lauren Mara Miller grew up in Spring Valley. “When I was a kid, they were still digging up the ground around my street and building houses,” Miller says. “We played everywhere—American University, the woods around Dalecarlia, Wesley Seminary. The whole neighborhood was our playground.

“No one ever told my parents about the chemical testing. My friend Marc and I would play outside every chance we could. I remember my next-door neighbor, Jim, saying, ‘If you dig in the ground, you can find treasures.’ So we dug holes in yards and gardens.” Their “treasures” were often thick pieces of glass.

“I could never figure out why my eyes burned all the time,” Miller says. “My mother kept an eye-wash cup handy and rinsed out my eyes all the time. It never crossed my mind that it wasn’t normal to come home with stinging eyes and get them washed.”

On a brisk autumn Saturday, Miller is going door to door to pass out fliers that alert residents to the Johns Hopkins survey. She knows that the study is imperfect, yet she’s determined to make sure every household in the neighborhood knows of it.

Miller left Spring Valley for college in 1974 and only moved back in 2007 to help care for her aging father. At first her health was fine, but after a few months she started to get “horrific” headaches. Her thyroid swelled. Doctors found cysts and nodules on her thyroid, an ovarian cyst, and overactive adrenal function. Her blood pressure was spiking. CT and MRI scans revealed a lesion in her brain.

“I saw at least four doctors,” she says. “No one could figure out why I was getting sick.” Eventually an immunologist diagnosed hypogammaglobulinemia, a rare immune-system disorder.

Miller was shocked that three of her childhood friends had died of cancers. The worst jolt came when she discovered that her boyfriend from the days of digging for glassware had died of a brain tumor. “Marc was my first kiss, my best playmate,” she says. “I was devastated—and angry.”

Miller knocks on the door of a stone house on Sedgwick Street, in the heart of Spring Valley. An elderly man answers.

“I grew up in Spring Valley,” Miller tells him. “I played in the yards and the creeks. Now I have growths on my thyroid. A brain lesion. And a blood disorder. I believe they came from exposure to the World War I chemicals tested in Spring Valley.”

She asks if he knew about the study. “Nope,” he says. “But I was treated at Hopkins for a blood disorder. My wife has a blood disorder, too.”

Across the street, Miller knocks on the door of another stone house. A gray-haired man in running gear greets her.

“I know about the trenches at the bottom of the hill,” he says. “That’s where they tied up the goats and set off bombs.”

The “Sedgwick trenches” ran behind his house. The Army dug the circular pits in 1918 and field-tested chemical-warfare agents, such as mustard gas and other lethal compounds. Soldiers tied animals to stakes in the circles, set off bombs in the center, and saw how quickly the animals died.

After the first bombs were found in 1993, the Army closed off the neighborhood, erected a sign that said danger—poison gas and evacuated 130 homes. Experts dug up 140 shells and projectiles. The Army surveyed 500 properties for buried weapons. It excavated 15 but didn’t find any munitions.

Researchers started to uncover what American University officials had known and when. Agreements between AU and the Army in 1920 revealed that the Army had buried munitions on or near the campus. In the 1950s, construction of a radio station on campus was stopped when workers unearthed a bomb. And the university called in the Army Corps to check for munitions before it built its sports complex in 1986. The Corps found no munitions but said the agency “could not disprove the burial of some materials.”

The university sold two building sites on property the Environmental Protection Agency had flagged as possible toxic-waste burial pits. A developer constructed houses on them. One was 4825 Glenbrook, across the street from Dieterich’s home.

In 1995, the Army declared that no further action was required in Spring Valley. It reopened its investigation, thanks in large part to Richard Albright, a lawyer and environmental scientist with the DC environmental department.

Albright used historical evidence and maps to identify contaminated ground in Spring Valley and on campus. Wielding metal detectors, he surveyed yards, especially on Sedgwick Street, where he had found records of trenches. The Army started to follow his leads.

In 1999, the Corps dug up two pits outside the South Korean ambassador’s residence, at the intersection of Glenbrook Road and Rockwood Parkway, unearthing 680 items associated with chemical munitions. In a separate dig, they found a 75-millimeter projectile containing mustard gas six inches deep in the ground.

In 2001 the Corps discovered a third pit at 4825 Glenbrook and dug up 400 more munitions. The Army then expanded its sampling of soil for arsenic and other carcinogens, and for the last 12 years it has been testing and removing soil across Spring Valley. The Corps began cooperating with the EPA and the District health department, set up a website with regular reports, and helped establish a Restoration Advisory Board of government officials and community members, which still meets monthly.

The Corps figured out the path of shells and mortars fired from the campus that described a “range fan” starting at the edge of American University and spreading down toward Dalecarlia Reservoir. The Corps notified residents within the area that their yards could hold bomb parts.

“It was a tough time in the community,” says Dan Noble, one of the project managers for the US Army Corps of Engineers Spring Valley project.

There would be many more.

• • •

Tom and Kathi Loughlin bought the new brick house at 4825 Glenbrook Road in 1994, on property that American University had sold to a developer, Lawrence Brandt. Tom Loughlin knew that World War I-era bombs had been discovered in Spring Valley the previous year, so he inserted a buy-back clause into his contract, in case toxic waste was found on his property. He had no idea what lay beneath.

In November 1997, Kathi Loughlin was diagnosed with a left frontal brain tumor. She was operated on at Georgetown University Hospital. Months later, the Army Corps of Engineers found the first of two disposal pits on the Korean property, just over the fence from the Loughlins.

The Corps would relocate the Loughlins twice as it excavated bombs from the Korean property as well as from theirs. In 2000, the family exercised its buy-back agreement and moved out.

The Loughlins’ live-in nanny, Patricia Gillum, was diagnosed with actinic keratosis, a precancerous skin condition that can be caused by sun or industrial chemicals, including arsenic.

In 2002, the Loughlins sued the United States government, AU, and Brandt, the developer, for $32 million. They charged the university with “fraud, deceit and outrageous conduct” based on documents showing that AU had known about the chemical testing and disposal since 1918.

The Loughlins also accused the developer of uncovering “laboratory equipment, jars, ceramic materials and a closed 55-gallon drum” while building the house. Workers had gone to the emergency room to treat eye and lung pain from the fumes. And when the developer tried to dump soil at a landfill, a bulldozer operator got sick.

Gillum, the Loughlins’ nanny, sued as well.

Camille Saum sued the federal government and AU at the same time. Saum had grown up on Sedgwick Street and lived there from 1947 to 1964. “I was a sickly kid,” she says. “My father was a doctor, but no one knew what was wrong with me.”

Saum would get so weak that she’d drop to her knees to crawl through her house. She was thought to have leukemia. Negative. She was tested for mononucleosis. Negative. It wasn’t until she was a teenager that she was diagnosed with pernicious anemia, a disorder that causes fatigue.

“Three-quarters of the homes in our part of the neighborhood had serious illnesses,” says Beth Junium, Saum’s sister. “Many of them had disturbed the soil by building additions. They all came down with cancer a year or two later.”

Junium counts the houses with cancer—“bad cancers, they all died”—and stops at seven. “I had an enormous growth on my thyroid,” she says. “Thank God it was benign. The grass wouldn’t grow in our yard. Our dogs got tumors.”

Camille Saum was eventually diagnosed with lupus and renal stenosis, a rare kidney disease that constricts the blood vessels. “I was examined by a doctor for NIH who told me my conditions could have been caused by arsenic poisoning,” she says. “But from where?”

In 2000, when she heard about the chemical-weapons testing at AU and the “Sedgwick trenches,” Saum started telling friends and relatives her diseases might be connected to the chemicals. A lawyer offered to represent her. She agreed and also filed an administrative claim for $10 million from the Army for failure to warn people of the chemicals.

The three cases—the Loughlins’, Gillum’s, and Saum’s—were joined in federal court.

• • •

The Loughlins might have had their hopes up because of a prior ruling by federal judge Stanley Sporkin, who presided over a 1996 case in which the Miller Companies, the principal developer of Spring Valley, sued the Army for failing to warn it about the buried toxins. Miller said the discovery of bombs in 1993 caused delays that cost it millions.

“When it buried live munitions,” Sporkin wrote, “the Army had in effect ‘booby-trapped’ the land.” He concluded: “No department of the government can so callously conduct itself, placing segments of the public in serious jeopardy, without appropriate warning of the hazards that exist.”

But because the case was settled out of court, Sporkin’s opinion never resulted in a final judgment against the Army. There was also an important difference between the Miller and Loughlin cases: The developer had shown monetary loss.

The Loughlins had to sue the government under the Federal Tort Claims Act, and a federal judge threw out all the cases against the United States under the “discretionary function exception.” This clause protects the government from being responsible for decisions that were made on the basis of an official’s policy judgment or choice. If the government and its leaders had to worry about getting sued, the law reasons, then government would suffer.

The Loughlins’ case against AU and Lawrence Brandt was settled out of court and was sealed. Gillum and Saum got nothing from their lawsuits.

“It’s terribly difficult and expensive to win a lawsuit on health impacts caused by environmental contamination,” says Harold “Buzz” Bailey, an environmental lawyer who has represented Spring Valley families. “You have to show chemical contamination exists in specific concentrations. You have to prove the exposure pathway. Air? Water? Rolling in dirt? How long? How did it actually get into your system? Then you must prove with scientific evidence that the chemicals caused a specific disease.”

Bailey has represented many Spring Valley residents for free. He advised the Dudley family, who lived on the corner of Rockwood Parkway and Glenbrook Road before their house became the South Korean ambassador’s residence. They suffered skin problems and cancers. Bailey tried to get the Corps to relocate residents along Rockwood Parkway while workers removed toxic waste a few yards away from where their children played. No dice.

“My role has become to persuade the Army to do the right thing,” Bailey says. “The laws are stacked against the sick people in Spring Valley.”

• • •

The Spring Valley Restoration Advisory Board convened in mid-November of last year at St. David’s Episcopal Church off MacArthur Boulevard. Tables in the community room were arranged in a square, with government officials among community representatives. Dan Noble took the front table with other Corps officials. Lauren Mara Miller sat in the back.

The Corps described its plans to knock down 4825 Glenbrook and dig under its foundation. Kent Slowinski and other community members questioned whether neighbors would be safe. Then the board turned its attention to the Johns Hopkins health study.

“We’re paying $250,000 to do a study of a transient population,” said Lee Monsein, a board member who has downplayed the risks of the buried waste. “It’s like throwing a quarter at it. It was totally worthless to begin with.”

John Wheeler, another board member, offered: “No one will be satisfied when the Hopkins survey is over.”

Malcolm Pritzker, also a community board member, held up the flier about the health study that Miller had distributed. “Where did these come from?” he asked.

Miller stood up and explained that she felt compelled to alert her neighbors to the survey. “Has anyone else in this room actually grown up in Spring Valley?” she asked. “Has anyone else had to bury their friends?

“There is a real problem here,” she said. “It’s not imaginary.”

After the meeting, Miller vowed to stay engaged. “The only way to get answers is to talk to people who have lived here their whole lives,” she says today. “They know the stories. They know who died and how.”

The persistent questions are why they died and whether buried chemicals contributed to their deaths—but those might turn out to be unanswerable.

• • •

Christine Dieterich needs answers to more immediate questions. She worries about chemical contamination in ground water and, especially, poisonous gasses escaping from the excavation across the street.

The Corps drilled test wells in front of her house and discovered high levels of arsenic and perchlorate. The latter’s health effects aren’t completely understood, but it’s known to cause thyroid problems. The EPA is still developing drinking-water standards. The Corps discovered perchlorate in ground water in a well near American University, and it was found in the ductwork in a building on campus “to a quantity deemed explosive,” according to Dr. Richard Albright’s book, Cleanup of Chemical and Explosive Munitions. Perchlorate was also found in an elevator shaft at Sibley Hospital and in test wells close to Dalecarlia Reservoir.

Thomas Jacobus, longtime general manager of the Washington Aqueduct—the system that takes water from the Potomac River through Dalecarlia to taps in the District and Virginia—says the source of the perchlorate remains a mystery.

“Of course we’re concerned if anything from Spring Valley becomes airborne and settles in the reservoir,” he says. “But we don’t believe there is any risk to the water operations. We find no connection between what might have been buried in the ground and our drinking water. But we are reassessing all the time.”

The Army Corps’ Brenda Barber also points out that Spring Valley residents drink city water, not well water, so high concentrations of the compound in its test wells isn’t an immediate problem. But under District regulations, all ground water must meet drinking-water standards.

“There’s a reason why they call it Spring Valley,” says Tom Smith, an Advisory Neighborhood Commissioner and Restoration Advisory Board member who has lived in Spring Valley for 30 years. “There’s a great deal of water under our homes. The perchlorate worries me.”

Dieterich is more concerned about the excavations across the street.

She and her husband appealed the Army Corps’ decision not to relocate their family. They lined up the support of the Restoration Advisory Board and enlisted Congresswoman Eleanor Holmes Norton, who made a personal plea to Lieutenant General Thomas Bostick, head of the Corps. The dig is expected to take more than a year, and Dieterich says she can’t afford to pay both her mortgage and her rent for that long. Her appeal was denied.

“Selling is a complete nonstarter,” she says. “Who would buy a house with so much uncertainty? The house next door was on the market for more than a year and didn’t sell. They just took it off the market.

“The frustrating thing for me is that the Army is always doing things piecemeal,” Dieterich says. “They only admit problems after things happen. Let’s say a siren goes off and I am at work. Our nanny grabs the kids and tries to get them into the basement or the attic before the gas gets to the house. It frightens the hell out of me.

“Nobody knows what’s under the ground.”

National editor Harry Jaffe’s first article about Spring Valley, “Ground Zero,” appeared in December 2000. It was awarded the Robert D.G. Lewis Watchdog Award by the DC chapter of the Society of Professional Journalists.

This article appears in the March 2013 issue of The Washingtonian.