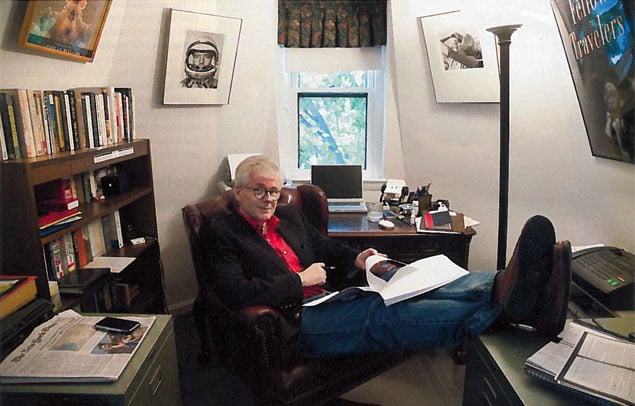

The view from Thomas Mallon’s third-story study in DC’s Foggy Bottom takes in the Kennedy Center and Watergate, landmarks built nearly in tandem in the 1960s. Yet when Mallon looks up from his desk and gazes through the window, he often conjures the cityscape of several generations past.

In his mind’s eye, smoke fills the air from the city’s gasworks. The Heurich Brewery’s giant plant occupies the swath of land now home to the Kennedy Center. Where the Watergate stands, there’s a park and memorial to heroes from the sinking of the Titanic.

“What has happened in the past, who walked these streets, certainly does work upon my imagination,” says Mallon. “I was once asked if I believed in ghosts, and my immediate answer was ‘Sure.’ ”

Mallon, 58, arrived in Washington in 2003 after years in New York’s literary scene and a turn as books editor at GQ magazine, where his Doubting Thomas column won a National Book Critics Circle Award. Memorable literary fiction doesn’t flourish along the Potomac in the quantity it does by the Thames, Seine, or Hudson, but Mallon couldn’t help himself. He was intrigued by how history here lay so close to the surface of everyday life.

Mallon set three of his historical novels in Washington—two in the years around the Civil War and a third during the McCarthy era after World War II. In his fiction, historical events—elections, assassinations, and the like—change the lives of characters swept up in their wake. He’s currently writing “a big, sprawling novel about Watergate.” His books usually don’t dwell on Washington’s giants, but this one will.

• • •

Mallon’s infatuation with Washington took root with Henry and Clara, the first of his DC-based historical novels, published in 1994. With that book in mind, we leave his Foggy Bottom home and head downtown to a three-story brick building in Chinatown around the corner from the Verizon Center. The building is home to Wok n Roll. In front of the restaurant is a placard saying that Wok n Roll was once the Surratt Boarding House—“the nest,” President Andrew Johnson said, in which the plan was hatched to kill Abraham Lincoln. John Wilkes Booth and his coconspirators frequented the boarding house as they plotted to assassinate Lincoln on April 14, 1865.

The assassination is pivotal to Henry and Clara. A critic noted that Mallon’s novels “tend to center on the Rosencrantz and Guildensterns of the American past”—referring to two minor but pivotal characters in Hamlet—and there’s no better example than Henry and Clara Rathbone, stepbrother and stepsister from a politically prominent family who marry against their families’ wishes. Henry serves with distinction during the Civil War, and Clara becomes one of Mary Todd Lincoln’s best friends.

The couple shares the presidential box at Ford’s Theatre with the Lincolns the night that Booth strikes, and Henry is knifed and badly wounded. Racked by guilt that he didn’t save the President, Henry begins a descent into madness and a tragic ending.

• • •

In Henry and Clara, Mallon followed his first rule of historical fiction: Don’t fight the facts. The novel got its start as a nonfiction account of the Rathbones, who in fact were with the Lincolns at Ford’s that night. Mallon invented plot details only when forced to. Well into writing, he discovered that Clara was three years older than her stepbrother, not five years younger, as many believed.

“I could have stuck to the lie about her age that I suspect Clara herself told for many years. I was, after all, writing fiction,” he says in his book In Fact: Essays on Writers and Writing. “But as I considered the matter, I realized how much more interesting—both psychologically and erotically—the truth would be. Having a Victorian heroine fall for the older stepbrother she acquires through her father’s remarriage conforms to all the expectations and archetypes. Having her fall for her new younger brother, as Clara did, has a bit of a kink to it.”

Wok n Roll draws a good crowd. In the late 1970s, when Mallon first came regularly to Washington to do research, the area around Chinatown was often deserted after dark. He remembers looking over his shoulder as he made his way to the Metro station.

Downtown DC now bustles with new buildings and construction. As we dine on Kung Pao shrimp, Mallon wonders if this link to Lincoln’s time will ever make way for something taller, better, more modern.

“How best to preserve infamy?” he says. “Of course, this isn’t where the Declaration of Independence was signed, but it is significant in its own way.”

• • •

Moving to Washington was a roll of the dice, a second big gamble for Mallon. In the 1980s, he left his faculty post at Vassar College in New York because he wanted to grow as a writer. “Tom has always wanted to write for readers other than academics,” says Dan Frank, his longtime editor at Pantheon. “Once he saw a way to make money from writing, he cut the cord.”

From 1991 to 1995, Mallon was literary editor at GQ. He says some of his friends regarded that period as his “literary midlife crisis,” but Mallon flourished, working with such journalists as the late Art Cooper and David Granger, now editor of Esquire.

Even as Mallon became more established in New York, Washington beckoned. “I’d been coming down to Washington a lot ever since the late 1970s—to see friends, to research and promote my books,” he says. “For much of that time, I’d had the idea of eventually moving here. New York has been the geographical constant in my life—I still keep a small apartment up there—but during the late ’90s when I was living in Connecticut, I found myself bored to tears, geographically, and thinking I ought to be where more of my interests lay.”

In 2003 he and his partner, William Bodenschatz, a freelance artist and designer, bought a snug townhouse (1,450 square feet) in Foggy Bottom. “Tom’s decision to leave New York was, to my mind, an ingredient to his basic sanity about what he does,” Frank says. “As alluring as New York City may be to writers, it is also a tremendous distraction. How can you not be looking over your shoulder to see what the other guy got? Plenty of opportunity for frustration, bitterness, disgust, competitiveness. Tom is genuinely interested in both history and politics. What better place to watch those spectacles than in Washington?”

• • •

From Mallon’s townhouse, it’s a ten-minute walk to the former site of the US Naval Observatory, which was housed at 23rd and E streets when it opened in 1830. Here, everyone from Lincoln to members of the public once gazed at the stars. But fog from the Potomac River and smoke from factories made scientific study hard and forced the observatory’s relocation in the 1890s to Massachusetts Avenue, where today it sits near the Vice President’s residence.

Now the Navy’s Bureau of Medicine and Surgery, the old observatory was central to Mallon’s second Washington novel, Two Moons. Set in the 1870s, it hinges on the discovery of the moons of Mars.

“So little of Civil War Washington remains, but this building does,” Mallon says. “This time period, the 1870s, was a great decade for this city. The street grid had been laid out, and everything was beginning to be filled in. At the beginning of the Civil War, Washington looked like the set in some old Western movie—dirt streets, half-built blocks. But by this point, only a few years later, the city was coming into its own.”

Among the true-to-life characters who inhabit Two Moons is Roscoe Conkling, a senator from Albany known as the War God because of his penchant for fisticuffs and political brawls. In the book, he becomes a key ally for the astronomers as they try to secure a more suitable home for their telescope. In Conkling, Mallon found a character too good to fictionalize.

“Flamboyant, cruel, and complicated, Conkling is a novelist’s bonanza,” Mallon wrote on a New York Times blogin 2007. “. . . [H]e was above all a man of action, one who detested the mere ‘carpet knights of politics,’ the commentators and chatterers who didn’t themselves live and die at the ballot box.”

• • •

Besides his seven novels, Mallon has written books about plagiarism, diaries, and Lee Harvey Oswald; Yours Ever: People and Their Letters came out last year. His essays and reviews continue to rock the literary landscape. In a 2006 New Yorker article, Mallon skewered what most consider one of the greatest books in American literature, To Kill a Mockingbird. Showing no deference to Harper Lee’s reputation, he annotated what he saw as the book’s dramatic shortcomings, stilted dialogue, and clumsy writing. It was classic Mallon: taking the familiar—perhaps places we hurry by every day—and presenting it in a new light.

For example, most people pass by St. Matthew’s Cathedral, near Dupont Circle, without a glance. A few remember it as the site of President John F. Kennedy’s funeral. Its threads of history, however, can be teased out further.

In his most recent novel, Fellow Travelers, Mallon builds the plot around two scenes at St. Matthew’s—Senator Joseph McCarthy’s wedding and his funeral. In the wedding scene, the nation is getting caught up in the Wisconsin senator’s witch hunt for Communists. It was at McCarthy’s wedding that Vice President Richard Nixon remarked, “The bride was lovely, but then I’ve never met a bride who wasn’t!” Mallon found the quote in old copies of the Washington Evening Star.

Writing Fellow Travelers, Mallon visited St. Matthew’s, walking the dozen or so blocks from his office at George Washington University, where he heads the creative-writing program. Standing in the back of the church, he imagined its past. In time, the old cathedral spoke to him, offering this scene of the McCarthy wedding for the book:

“[The couple] turned from facing the huge mosaics behind the altar and began their march to the cathedral’s doors. . . . In the meantime he gazed at the huge red-and-white marble pillars that seemed to be running with blood, and put a quarter in the poor box: he’d taken the extra coin from his dresser when he left this morning, forgetting that, even if there was a full Mass with the wedding, there wouldn’t be a collection.”

• • •

Mallon grew up in an Irish Catholic family on Long Island. These days he can’t quite believe he lives in a city where the buildings don’t tower to the sky. Still, Mallon has grown to love his new surroundings. He has Christmas dinner every year at the Hay-Adams hotel and knows well the story of the two men who once lived on the site: famed author Henry Adams and John Hay, an assistant to Lincoln -and later a Secretary of State.

Mallon attends local readings and is a staunch advocate of the city and its writing community. A few years back, he regaled a writers’ conference here with tales about DC’s past. Local writer and blogger Catherine Mayo calls Mallon “a gracious writer, both on and off the page.”

“There’s no place like New York,” he says. “I grew up there, and a part of me will always be there. But one of the great things about Washington is it’s still a city where the sky can be seen, a place where you can breathe. Things hang in the air here. Sometimes, when the writing is going well, you feel like you can still peel it all back. See things as they once were.”

Tim Wendel is the author of eight books. His latest is “High Heat: The Secret History of the Fastball and the Improbable Search for the Fastest Pitcher of All Time.”

This article appears in the July 2010 issue of The Washingtonian.