One night this past winter, in a week when nothing was working

out, Meguiel Merritt called his ex-wife and asked her to pray for

him.

“You been drinking?” she asked.

He’d been sober for eight years, but Merritt knew why she

asked. As their marriage had unraveled in the early 1990s, he’d started

drinking heavily, a prelude to a lost decade on crack cocaine.

The problem now, though, wasn’t drugs. It was money. He was 52

years old and had a full-time job with benefits as an assistant janitorial

supervisor at Howard University. But he was living in a homeless shelter

off North Capitol Street, in a room with six other men.

Merritt had always felt his needs were simple: He wanted an

apartment of his own in DC. His hometown. An efficiency would do, so long

as his TV got the Westerns he loved and there was a gas stove to cook

liver and onions, chicken and sliced potatoes, and other beloved

meals.

But rents had rocketed so fast that a man making $29,000 a year

no longer felt welcome. He’d seen listings east of the Anacostia River for

less than $800 a month, but he couldn’t go back there, not without seeing

ghosts from his old life.

The week Merritt called his ex-wife, a rental rep at one DC

building told him he was too deep in debt to his last landlord to qualify

for an apartment. Then, when he looked outside the District, in Greenbelt,

to see if rents were better, a building agent said he had nothing for less

than $1,000.

If he wanted to live in or around DC, Merritt began to fear,

he’d need a second job. But after starting an online exam for a night job

sorting mail for the US Postal Service, the website malfunctioned,

stranding him mid-test.

Merritt started to think about a scene in the movie The

Color Purple, when the character played by Whoopi Goldberg puts a

curse on her good-for-nothing husband. “Until you do right by me,” she

tells him, “everything you think about is gonna crumble.”

The past weeks had left Merritt feeling as though someone had

put a “mojo” on him. He’d made mistakes enough in life, he knew, that

blame for the greater part of his troubles lay on his shoulders. But he

needed some sign that the family he’d wronged over the years wasn’t

actively rooting for him to fail.

His former wife assured him that was not the case.

Would she be willing to say a prayer for him?

She told him she would.

• • •

One wet morning as we drove together to see the high school he

never graduated from, Merritt let his mind flood with daydreams. “I’d love

to lay out on the beach, look at the white sand,” he said. Then, in the

present tense, as if already there: “I have two bikinis on each arm and

say, ‘I wonder what the poor people are doing.’ ”

But as he looked through the rain-blurred windshield of his

truck, he saw not paradise but the streets—Lamont, Warder—where his life

had gone under. “In my addiction, I’d come here to party, to buy drugs, to

meet women,” he said. “You had to be careful in this area because if they

didn’t know you, they’d rob you real quick, real fast.”

It was 10:40 am on a Saturday, and we pulled into an empty

parking lot overlooking the football field at Roosevelt High School, in

DC’s Petworth. Merritt had dropped out in 11th grade, when the money from

his minimum-wage job and the girls his paycheck attracted made him feel

like more of a hotshot than any honor roll.

“I should have stayed in school,” he said now, the rain still

coming. He rolled down the window a little: Glistening out there was the

field where he once might have worn a football uniform but never did. He

was husky even then—six-foot-one, 250 pounds. But when he quit school,

football was another thing that got away from him.

Merritt is a heavy man with a baby face, glasses, and a voice

somewhere between a rasp and a whisper—a gentle giant, some say. His half

year at the shelter hasn’t been kind to his body. The kitchen is off

limits to residents, so Merritt, a onetime cook, has indulged a weakness

for carryout. His weight has ballooned to 350 pounds. He wheezes as he

climbs stairs. He sometimes has to stop for breath.

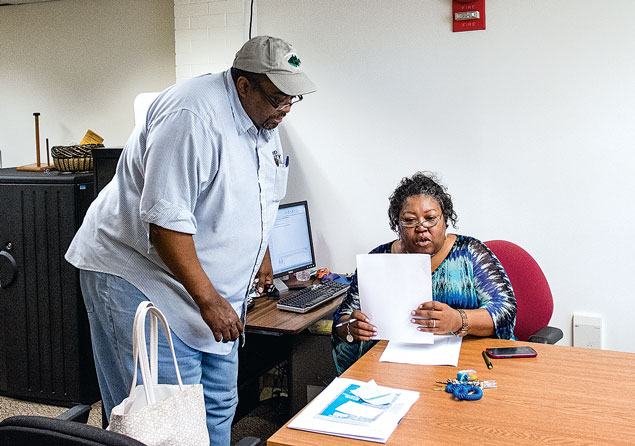

When we spoke in his basement janitorial office one day,

Merritt told me he expected neither handouts nor some music-video fantasy

vacation. He wanted only the barest dignities of a man who had held the

same, steady job for nearly 30 years. “I don’t need to live like the

Joneses,” he said. “I just want to be more comfortable.”

I asked him what that meant. “A little money in the bank, to

where I can pay my bills and don’t have to worry: Will I make the water

bill? Will I make the electric bill? I’d like to just sit down and write

those checks and just live that American dream.”

But in his search for that dream’s bedrock—his own place—he has

struggled. “My problem is I want it today,” he said. “I just want to get

out of the shelter and start living again.”

He’s too old to live in a dormitory with a half dozen

strangers. To shower in a group bathroom. To swallow warmed-over slop from

a food kitchen. To ask for a pass to stay out after curfew.

But the new DC isn’t handing out second chances the way it used

to. So he works and he waits.

When I followed him around the job one morning—HOWARD

UNIVERSITY stitched above the left pocket of his denim work shirt—he

seemed invisible to the undergraduates whose toilets he fixes and whose

dorms he cleans. The bright lives they were racing toward, he knew, would

have little in common with his.

Merritt allows himself one DC Lottery ticket a day; a lucky

number sometimes feels like his only shot at a new life. But mostly he

practices patience. A life of wrong turns can’t be righted overnight. “I

need to stop rushing God,” he says, “because it’s on his time, not

mine.”

• • •

The trim house on Sixth Street, Northeast, where Merritt spent

most of his childhood borders the leafy campus of St. Paul’s College, in

the District’s Edgewood section.

For his parents, it was a beacon of middle-class arrival. The

family had lived in a series of small apartments in rougher parts of

town—in the last place, a pyromaniac regularly set the building

ablaze—before finding their way to this pistachio-green house with the

white stone chimney at the end of a quiet block.

Meguiel Merritt was born in 1960, the middle of three children

and the only boy. His father, Charles Jackson, returned from the Vietnam

War to a job as a National Park Service groundskeeper on the Mall. His

mother, Eula, started as a cafeteria aide at Howard University and was on

a slow but steady path to management. (She retired in 2002 as operations

manager for residence life.)

Meguiel got decent grades and was a bruiser at playground

football matches. For a time, it looked as if he might hoist the family

further up the economic ladder.

He had watched his mother and aunt in the kitchen and studied

their tricks for roasting chicken and grilling pork chops with garlic

powder and seasoned salt. By the time he was ten, he could cook for the

whole family. When I ask what first drew him to the stove, he tells me

about a time when he was a boy and his mother was sick: “I said, ‘I’ll go

down and fix you something.’ She said, ‘That’s the best soup I ever ate.’

Maybe she was making me feel good. But she ate it all.”

But cracks in the family’s foundation turned into

sinkholes.

Memories of Vietnam stalked his father, who lost himself to

alcohol and began running an after-hours gambling hall out of a nearby

house. “A gyp joint,” Merritt calls it. He says his father started giving

him beer at age seven. “He woke up and got liquor before he went to work

and came home with a bottle in his pocket.” (Charles Jackson died some 20

years ago, of cirrhosis.)

Hearing a bang in his parents’ bedroom one night, Merritt

dashed upstairs to find a hole in the wall and a .38 revolver in his

father’s hands. His dad was convinced Vietcong were on his tail. When his

father turned his rage on his mother—bruising her face and bloodying her

lip—Meguiel thrust himself between them, hoping to deflect his father’s

anger onto himself.

When I ask Merritt’s mother why he quit school at 17, Eula

Jackson says a boy who had moved in down the block pressured him to skip

classes.

But when I tell Merritt what his mother said, he shakes his

head. There were plenty of other reasons for his dropping out, he says,

not least a desire to prove himself his own man.

In school, kids teased Meguiel about his size, calling him

Pillsbury Doughboy. After he dropped out, no one messed with him: He had a

.22 revolver and a homeboy who had his back. The pair often passed the

school day in the park with a bottle of wine.

While driving around together one morning, I asked Merritt what

became of that friend. He slowed his truck and pointed to a gas station at

the corner of Florida Avenue and Third Street, Northwest: “He stands there

and begs for change.”

• • •

For all his shortcomings, Merritt inherited from his parents a

belief in the virtues of work. A month after quitting school, he got a job

as a stock clerk at Woodies department store and then, at 18, as a

dishwasher at a downtown DC restaurant. He met a woman who worked as a

table busser there, a Jamaican immigrant ten years his senior. Soon a son,

Meguiel Jackson, was born.

He and the boy’s mom weren’t committed, though, and two years

later, in 1982, he married a woman who made sandwiches at a downtown

Wendy’s, where he was a cook. They were both 21, and she had a young

daughter from a previous relationship. They moved in together. Merritt

left his son’s upbringing to the boy’s mother.

When Merritt was 25, his mother, then an executive housekeeper

at Howard, helped him get a second job, as a daytime janitor in the

school’s dorms. He traded up restaurants, too, leaving fast food for an

evening job at a Bob’s Big Boy in Aspen Hill. He worked his way up from

dishwasher to first cook and made enough of an impression on his bosses

that the company sent him to culinary school, from which he returned as

the restaurant’s head chef.

The extra pay lifted his new family from a one-bedroom

apartment in Columbia Heights to a two-bedroom in Aspen Hill. But the long

hours took a toll. To let off steam, he and a waiter he’d befriended began

drinking together on the job, from 10 pm until their midnight quitting

time.

“I’d get off work at 12 o’clock, go home, and get up hung-over

at 4 o’clock” for his janitorial job, he says. “I did that for five

years.”

By the time he finally left the cooking job, it was too late to

reverse the damage his alcoholism and financial insecurities were doing to

the marriage. In his rush to outfit their new life with all the trappings

of success—a new Toyota 4Runner, a leather living-room set—he and his wife

had piled up $72,000 in credit-card debt. When I ask about the discolored

scar tissue on his knuckles, he tells me it was from a night when he grew

so frustrated that he drove his fist though a door, prompting his wife to

call the police.

The couple split in 1991, and his life entered a tailspin. He

filed for personal bankruptcy and moved into an apartment on South Capitol

Street with a female housekeeper he worked with at Howard. They started

smoking three to four $10 bags of crack on the weekends. It soon became a

$150-a-day habit. The apartment “turned into a crack house,” he says.

“People came to the door all hours of the night, just to get high and

smoke.”

Yet even in the grips of addiction, he kept showing up for

work. After lunch, when work slowed, he closed the door to the tiny

janitorial office in the basement of Carver Hall, an all-male dorm, and

got drunk. He kept a bottle of rum in the desk drawer and served himself

in a 7-Eleven soda cup. He wore sunglasses indoors to hide his dilated

eyes and chewed gum against the odors.

Some nights, when he was too strung out to get home, he slept

on the floor of the janitors’ locker room, a violation of rules. Then one

night he fathered another child, a girl, in a brief encounter with the

wife of a friend’s friend—a woman he says came on to him after he’d downed

too much Jack Daniel’s. He bailed on that daughter, just as he had his

son. Though he sent money from time to time, both were raised by their

mothers and grandparents.

I ask how his life spun so out of control. “After the divorce,

I had to figure out: What am I going to do?” he says. “I was young, mad,

angry. I was angry that I messed up my marriage, that I worked so hard for

this woman—the money, the cars, the furniture I bought. And then I’m out

here assless with nothing.”

If working hard and doing right had led to this, what was

the point? he asked himself. Why not just take the fastest route

to feeling good?

In the summer of 2005, Merritt’s boss at Howard sat him down in

her office. She held up a card for an inpatient detox program at DC

General hospital.

“Take this card or take a pink slip,” she told him. “You

decide.”

His seven days at DC General were a boot camp of counseling

sessions and scared-straight talks. Other addicts told stories of falls

far steeper than his. Some had slept on the streets, eaten out of garbage

cans, contracted HIV, been thrown in jail.

There but for God’s grace go I, he thought.

He relapsed once that summer—a four-day bender—before getting

clean for good on July 1, 2005. With no home to return to, he moved into a

halfway house.

As his recovery progressed, Merritt began night school. He

earned a GED and certificates in heating, ventilation, and air

conditioning. In 2009, his supervisor at Howard took note of his

achievements and recommended him for a promotion, from lead custodian to

assistant supervisor. The new post would put him in charge of checking

employees’ time sheets, troubleshooting larger maintenance problems, and

responding to requests that students submitted through a web portal called

ResQuick Fix.

“He said, ‘I’m scared, Mama,’ because he felt it was a lot of

responsibility,” Eula Jackson recalls. “I said, ‘You can do it.’

”

He left the halfway house in 2008 and moved in with his mother.

He was 48 years old.

At her urging, he had started showing up at Sunday services at

her church, First Rising Mt. Zion Baptist, in the Shaw neighborhood. I

went there with Merritt on Easter Sunday. While waiting in a hallway to

meet the pastor, he told me faith hadn’t come easy.

Churchgoers said they cared for him, but he was suspicious of

their seemingly selfless declarations. They told him they loved him, but

how could they really? For all they knew, he could have been a thug who

would have robbed them on the street without a second’s

hesitation.

He sat in the last pew by himself for weeks: “All the ways in

the back. I listened and I listened, and one day God said, ‘Come up and

join.’ ”

At an orientation meeting, he met a single mom—a secretary at a

public school—and asked if she wanted to meet sometime to talk about the

Bible. They started going out for nachos once a week. When her car broke

down, he drove her mother and teenage daughter to appointments while she

was at work. He hopes that the friendship might one day lead to something

more.

By 2010, Merritt had saved enough to leave his mother’s house

and rent a one-bedroom apartment, for $750 a month, in Washington

Highlands, a violence-plagued section of Southeast DC. His furnishings

were spare—his nightstand was a small folding table a student left behind

in the Howard dorms—but it was his own place.

Everything seemed to be falling into line: the GED, the

promotion, the apartment, the new woman in his life. Still, at the edges

of his happiness, doubts menaced. His redemption would mean nothing, he

realized, if he didn’t try to make things right with his

children.

• • •

I visited Merritt’s son, Meguiel Jackson, in late March at an

Oxon Hill dental clinic where he works as a billing-and-coding specialist.

Jackson, who is 33, has his father’s round face and gravelly

voice.

As a boy, Jackson said, he experienced his father as an

absence. They barbecued and fished on his occasional visits. But Jackson

felt a hollowness while visiting friends with intact families or watching

TV shows like Family Matters, the 1990s sitcom about a

middle-class African-American family in Chicago. “You’d see how the

parents would be there, and at night they’d help the kids with homework,

they’d tuck them in, or just talk to them and read them bedtime stories,”

he said. “Those were the times when I really wanted him around

more.”

Like his father, Jackson quit school at 17 and soon had his

first child, a girl who would be raised by her mother. In his twenties, he

became a street-corner drug dealer whose “family,” he said, were the guys

he sold drugs with. He spent a total of eight years in prison for drug

offenses and illegal firearms possession. In 2009, toward the end of his

last sentence, he slipped a note into a letter to his half sister and

instructed her to give the note to their father.

He had found God in prison and earned a high-school-equivalency

degree. But something was still missing: “I needed my strength. I felt

like he was my strength.” In the note to his father, he said, “I was

telling him I love him and I need to see him.”

As he stepped into the visiting room at DC’s Correctional

Treatment Facility, Merritt had a waking nightmare: He imagined the guards

deciding that it was he—not his son—who belonged behind bars.

“Son,” Merritt began when they saw each other, “I’m sorry I

wasn’t there for you.”

Jackson listened and forgave him. “I wanted him to know that he

was not the cause of my being in prison,” he says today. “I made my own

decisions.”

Though too rare, the times they’d spent together had been

meaningful, Jackson told his father. One time in particular had lodged in

his mind. Jackson was 12 or 13, and they’d gone fishing with Merritt’s

friends. Everyone was reeling in whoppers—except for Jackson, who was

pulling in small fry.

“Don’t worry, son,” his father said, seeing the boy’s

disappointment. “Keep throwing that line out there. Soon you’ll get a big

one.”

• • •

The day Meguiel Jackson moved from prison to a halfway house,

in 2009, his father showed up with a wardrobe’s worth of gifts: tennis

shoes, three pairs of jeans, three shirts, boxers, T-shirts, socks, plus

deodorant, shaving lotion, toothbrush, toothpaste. Merritt gave his son

money to buy sharp clothes for job interviews (including the one that got

him work at the dental clinic). He treated him and Jackson’s second

child—a young son Merritt had affectionately nicknamed Fat Baby—to trips

to restaurants and the zoo.

“You can’t make up for lost time,” Jackson says. “All you can

do is enjoy the time you have, and that’s what we do now when we’re

together.” They talk about football, women, children, and “my deepest

feelings,” Jackson says. “If I’m going through something or hurting over

something, he’ll listen to me and give me his advice. Those are my special

times now.”

Merritt’s teenage daughter, meanwhile, needed even more help.

She had fallen in with a rough crowd and was skipping school. Her mother

was jobless and drinking again. He looked at his daughter and saw himself

at the same age, chasing thrills instead of a future. Merritt and his son

had fallen off the precipice; it was still early enough to save his

daughter from the same fate.

Merritt bought her soap and deodorant and paid for hair and

nail appointments. There was ugliness enough in her life. At the very

least, he thought, he could “try to make her feel young and

pretty.”

He found a good public charter school and pleaded with her to

attend. She told him she was going, but school officials called to say

she’d never shown up. He discovered she’d lied to the school, too, saying

she had a baby to take care of. When Merritt confronted her, she made more

excuses, saying she couldn’t go to school without nice clothes. Merritt

gave her more money, and more. After all those years of neglect, he felt

he owed it to her.

Eula Jackson, who raised her granddaughter from ages 7 to 13,

tells me her son had perhaps too much faith in the possibility of rolling

back time. “It’s hard,” she says, “because I guess in the back of the

child’s mind is ‘Where were you when I needed you?’ ”

He spent so much on his children that unpaid bills piled up. He

soon owed $400 to Sprint for cell-phone service, $290 to Comcast for

cable, $45 for gas. Then, after the 2004 Chevy TrailBlazer he’d bought on

credit broke down, an auto shop handed him a bill for $1,700. When he

couldn’t pay in full, the shop impounded the truck and charged him $40 a

day for storage, adding on another $500 before he could scrape together

the cash.

He had left his one-bedroom apartment in Washington Highlands

for a studio across the street, where rent was $100 a month less. But soon

he was several months behind. He came home from work one summer day last

year to find an eviction letter in his mailbox.

He gave his bed and dresser to his son and stashed most of his

clothes, family photos, and other belongings in a janitorial storage room

at Howard. It was early summer, and the students were gone. He slept in an

empty dorm room for a few days before facing what came to seem inevitable:

a return to the homeless shelter he had lived in some seven years earlier,

just after the detox program, when his life had hit bottom.

• • •

Emery House occupies an institutional-looking brick building on

a gritty strip near North Capitol Street in DC’s Eckington section. The

place was once a public school and later an emergency homeless shelter

that kicked men out at 7 each morning. Then in 2005, the city and DC’s

Coalition for the Homeless, which runs the shelter, identified a growing

class of homeless men: those with jobs.

Rents and housing prices in the District had soared over the

first decade of the 2000s. From 2000 to 2010, the supply of apartments

whose rent and utilities cost less than $750 a month, in

inflation-adjusted dollars, fell by half—from 70,600 to 34,500, according

to a report by the nonprofit DC Fiscal Policy Institute. Meanwhile, the

number of apartments costing more than $1,500 grew from 12,400 to just

over 45,000, more than tripling.

Those shifts hit low-income residents hardest. “One of the

problems with spending so much of your income on housing is it makes you

very vulnerable to that one economic shock, which can leave you homeless

or in severe crisis,” says Jenny Reed, the institute’s policy director.

“Our research shows that a lot of people who have severe housing burdens

are working, and working full-time. It’s just not enough to get

by.”

In 2006, Emery House remade itself into the city’s first

homeless shelter for the employed—those with at least 20 hours of work a

week. Though they pay no rent, the men must place at least 30 percent of

their paychecks into an escrow account—as a cushion for their reentry into

the real-estate market and as practice for the budgetary tightrope people

with low incomes need to walk in an increasingly affluent

city.

I visited Emery House in early February and was given a tour by

the current director, Xavier Parker, who is 51 and has the harried air of

a big-city high-school principal.

As we walked through the halls in the middle of the day, when

most of the men were at work, he told me that though nearly all the

residents are African-American, the population is in other ways diverse.

The house’s 72 residents range from ex-cons, day laborers, and dishwashers

to bike messengers, a man who works for a DC Council member, and a

graduate student.

Emery, which operates on District and federal funds, has

on-site counselors who help residents search for better jobs and housing.

On paper, the shelter gives men six months to regain their economic

footing before sending them on their way.

“What’s the longest guys have been here?” I asked as we stepped

into an elevator on the second floor.

Parker shot me a sidelong look. “You don’t want to

know.”

Two years?

“Four,” he said. “The average is one year and some change. Many

are working 20 to 30 hours at $8.25 an hour. That’s not enough for them to

move forward in DC.”

• • •

When Meguiel Merritt was there the first time, in 2005, Emery

House wasn’t yet a “work/bed program.” But in other ways the place was all

too familiar, and coming back felt like a failure.

God is showing me I did wrong, he thought. Maybe I

moved out too fast. Maybe I wasn’t ready.

The intake counselor remembered him and assumed he’d relapsed:

“He said, ‘What kind of drugs did you take?’ I said, ‘Slim, it’s not

drugs. I just mismanaged my money.’ ”

It was July 2012. The staff settled Merritt in a room on the

first level, with linoleum floors, gym lockers, and rows of single beds. A

half dozen other men shared the room.

He was courteous to his dorm mates but mainly kept to himself.

He’d wake at 4 every morning, watch the news on a portable TV he kept in

his locker, then shower for work.

When I first visited, in the frigid darkness of an early Monday

morning in February, Merritt emerged from his room with a towel over his

shoulder and padded the long hall to the showers. Before leaving for work,

he signed his name in a three-ring binder at the front desk—the men must

account for their comings and goings.

I asked whether he had eaten the house breakfast, which is

trucked over the night before by DC Central Kitchen. He told me he hadn’t:

Today it was a mélange of eggs and grits that residents had to warm up

themselves in a microwave. He gave it a once-over but decided he couldn’t

stomach it.

“This is a nice spot,” he said of Emery House. “But it’s not my

home. I’m not trying to get comfortable.”

Emery requires residents to call at least four landlords a

month to inquire about housing. Merritt had aimed high. With the money he

was putting in escrow and maybe a second job and a loan, he thought he

might have enough to buy a small house somewhere, even in the suburbs. He

spent a whole day at a homebuyer’s conference at the Washington Convention

Center, learning about credit ratings, mortgages, and down

payments.

But as time passed, he grew dejected. I joined Merritt at one

of his monthly meetings with Emery’s housing specialist, Herbert Baylor.

When I arrived, the two were scrolling through listings on RentToOwn.org.

On the wall behind Baylor’s desk was a worn poster of a locomotive turning

a corner in the woods, puffing steam. “Initiative,” it read. “Nothing can

stop the power of persistence.”

All the listings in DC—at least those west of the Anacostia

River—were out of reach.

“Should I pick another city?” Baylor asked.

“I don’t want to go that far,” Merritt said. “What about

Montgomery County? Aspen Hill?” It was where he’d lived while married and

working at Bob’s Big Boy, and where his stepdaughter and her kids now had

a home.

Baylor looked skeptical. He pulled up the listings: Homes for

sale there ran from $400,000 to $599,000. Even Baylor looked surprised:

“This is crazy.”

He then found a four-bedroom rental in Beltsville for $800 a

month.

“Let’s print that one out,” Merritt said.

But as he read the fine print, light drained from his face: The

$800 covered one room. The other three would be occupied by other tenants

and the owner.

“Oh, hell, no,” Merritt said. He was in his fifties.

He wanted privacy and quiet, not a frat house.

Baylor told me no Emery House resident had gone directly from

the shelter to homeownership. It was a leap for which none had the

finances. But the staff didn’t want to pour water on Merritt’s dream. They

understood why a man who had held a full-time job for three decades—even

one whose life had its share of stumbles—might want a place to call his

own.

When I told Jenny Reed, of the DC Fiscal Policy Institute,

about Merritt, she said that cases like his had become “very common.” The

District’s rebirth—from murder capital to hipster haven, as the city’s

promoters would have it—has thrown its inequalities into sharp relief, or,

more often, papered over them.

According to government statistics Reed showed me, the top two

jobs held by DC residents—by employment total—are lawyers and other legal

professionals (annual median wage $153,640) and various kinds of managers

($126,240). Third and fourth in number—but far distant in pay—are the

people who answer their phones and clean their buildings: administrative

assistants ($50,575) and janitors ($24,160).

Merritt’s pay last year—$29,167 before taxes—is more than twice

the federal poverty line for a single person. But what that buys in DC is

ever-shrinking.

“There are guys 50 to 60 years old living in a [single] room,”

says Karen Douglas, a veteran social worker who is the clinical supervisor

at Emery House. “Nobody thought, ‘At 60 I’m going to retire and I’m going

to be in a room, just me and enough space to turn around in.’

”

The men at Emery House, Douglas says, look with mixed feelings

at the rehabbed homes—fresh paint, newly landscaped yards—that shimmer

between the peeling places where their grandparents once lived. “You know

you will never be in a position to move your kids into a home like that,

never have a place big enough to have a Thanksgiving dinner in the

neighborhood you grew up in,” she says.

So they ask themselves, “What am I working for? How do I keep

hope up?”

• • •

Merritt’s friends and relatives worried that the stress of

returning to the shelter would trigger a relapse. But they underestimated

his resolve. One weekend, he drove me to the square brick apartment

building on South Capitol Street where he had lived in the darkest days of

his addiction. We stopped in the driveway.

I asked how he felt, seeing the building again. “It’s over,” he

said. “I don’t forget. But I don’t want to go back.”

The problem was no longer his addiction; it was his recovery.

He had assumed that if he stayed sober, his fortunes would follow an

upward course.

As winter turned to spring, Merritt realized that his optimism

had blinded him to certain hard truths: “I was trying to please everybody

in my life—please my son, please my daughter—and trying to make them

happy. I was trying to buy their love.”

His friends and the caseworkers at Emery told him that no

amount of money could buy back those lost years. He had to take care of

himself first. He had to pay his rent on time and learn to budget. His

example—of hard work, responsibility, and adversity soldiered

through—would be the best gift he could offer his children.

• • •

At the end of February, Xavier Parker and the counseling team

at Emery summoned Merritt to a meeting: His time was up. They had already

granted him one two-month extension; they couldn’t approve his request for

a second. Merritt had wanted more time to build savings and move closer to

his dream of homeownership.

But the staff at Emery felt that another extension risked

breeding dependence. Unlike most of the other residents, Merritt had a

full-time job with benefits. What he needed more than anything, they felt,

was to learn self-sufficiency and align his dreams with his

income.

A few days later, he approached Douglas in the hall and thanked

her. “He asked me, ‘Would it be okay if I gave you a hug?’ ” she

recalls.

When I next saw Merritt, I asked what precisely he’d thanked

Douglas for.

“Tough love,” he said.

• • •

Within two days, Merritt had found a listing in the

Express: a room for $525 a month, near the Benning Road Metro. He

had spoken to the landlord and was about to drive to see it when Douglas

called with another lead. A friend of a friend—a retired gentleman in his

sixties—had recently remodeled his house on West Virginia Avenue in

Northeast DC and had a furnished second-floor room to rent for

$550.

The man lived in the basement and was planning to lease two

other upstairs rooms. When those tenants moved in, Merritt would have to

share the second-floor bathroom and kitchen. It was a far cry from a home

of his own, but it was clean, the furniture looked solid and new, and it

was an easy drive to family, church, and work. He signed the paperwork the

next day.

The following afternoon, a Saturday, he double-parked outside a

red-brick rowhouse and I helped him carry in the last of his belongings.

His room looked freshly painted, with bright-yellow walls, a large wooden

dresser, and a cable-ready TV. Two big windows overlooked grassy athletic

fields and a children’s playground at Gallaudet University.

We went back down to the truck, and Merritt took out two

plastic bags of groceries, heavy with fruits and vegetables. He was ready

to cook his own food again and to return, he hoped, to a healthier

weight.

When we finished unloading, it was late afternoon. Merritt

looked exhausted. He had gotten up at Emery at 3:30 that morning, anxious

about the days ahead. Before we met, he had washed every last stitch of

laundry, gotten a haircut, changed the oil in his truck, and stopped at a

Big Lots for a comforter and queen-size sheets for his bed. “A new start,”

he said.

We got back into his truck and drove away on another errand. “I

still want that house,” he told me. “But you know, you got to crawl before

you can walk.”

Contributing editor Ariel Sabar is the author of two books,

including My Father’s Paradise: A Son’s Search for His Family’s Past. His website is arielsabar.com.

This article appears in the September 2013 issue of The Washingtonian.