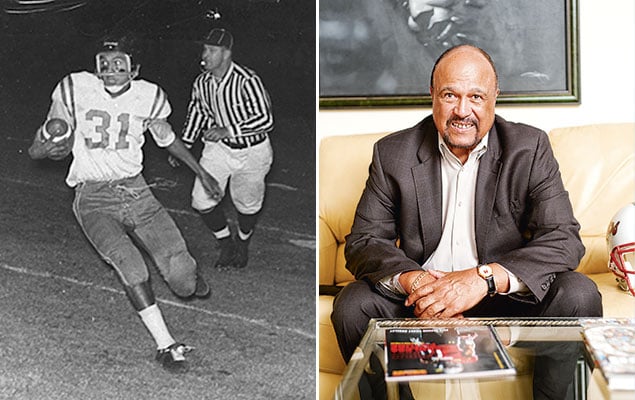

Darryl Hill

Gonzaga High School, Class of 1960

Darryl Hill was the first African-American to play football at Gonzaga, then became the first to play for the University of Maryland in 1963. Hill now chairs the nonprofit Kids Play USA Foundation, in Laurel, whose goal is to eliminate financial barriers in youth sports.

I didn’t do a lot of out-of-school socializing with my classmates. When I got to Gonzaga in 1956, blacks couldn’t go to theaters and restaurants downtown. I remember the first time I went to a downtown theater—that happened while I was at Gonzaga. My senior-class trip, which was traditionally to Ocean City, had to be changed to Sandy Point Beach because Ocean City was segregated. But the black and white kids got along fine and hung out together at recess, and of course I traveled a lot with the teams I was on. There were only 12 African-Americans in the whole school.

Gonzaga didn’t care how much money your daddy had, and the tuition was never that severe. The kids weren’t rich—these were the academic elite. The Jesuits expected three hours of study every night. Gonzaga challenged you to be excellent, and if you were excellent they responded in kind.

The Jesuits refused to leave the inner city. When things started getting rough in the ’60s, a lot of schools started moving out. Gonzaga stayed, which I think is really special.

Those four years were as good a four-year block as any in my life. I felt like I was treated more than fairly. I was supported and encouraged.

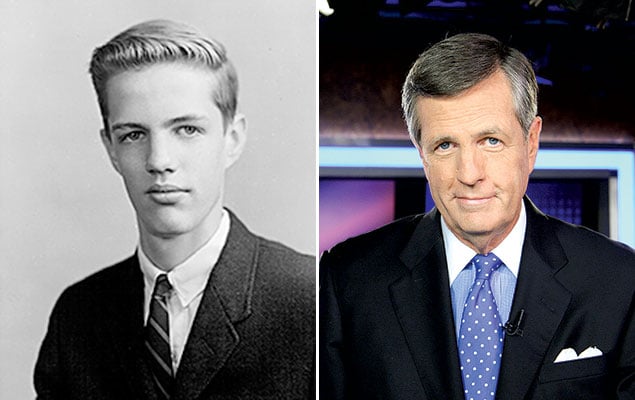

Brit Hume

St. Albans School, Class of 1961

Brit Hume covered Congress and the White House for ABC for almost 25 years before moving to Fox News in 1996, where he’s a senior political analyst and a commentator on “Fox News Sunday.” He lives in Arlington.

St. Albans was strict, full of the sons of ambassadors and senators, but it was no big deal. Senator George Smathers would come to our games. John Kerry was my classmate. During the Army-McCarthy hearings, I saw Kerry in a fistfight with the son of the Secretary of the Army.

It was an Episcopal school—there was chapel every morning. It salted in me a germ of faith that would later become very important. I regret that they don’t have chapel every day now, because I think it helped me.

The school had high standards. I was a lousy student, and they were glad to see me go. Girls were a major distraction—at National Cathedral School, on the same grounds. After home football games, they had what were called tea dances. Girls from NCS and other schools would come, and it was kind of a mixer. There was no tea. It was Coca-Cola and doughnuts.

The Bishop’s Garden was a favorite place to smoke because the hedges were high. A bar up the street called the Zebra Room was a big hangout. You weren’t supposed to be served until you were 18, but we were all 16, 17. We were always looking for places that would serve us.

Cokie Roberts

Stone Ridge School of the Sacred Heart, Class of 1960

Cokie Roberts is a political commentator for NPR and ABC. The daughter of former Louisiana congressman Hale Boggs, she still lives in her childhood home in Bethesda, four miles from Stone Ridge.

Stone Ridge was the best education I’ve ever gotten—certainly as rigorous as Wellesley. We had a uniform in the spring and fall that was a medium-blue shirtdress—it was really ugly. Our winter uniform was a gray flannel skirt, white cotton blouse, and navy-blue blazer. And brown oxfords—those were terrible. You kept loafers and a trench coat in your locker because you couldn’t be seen off-campus smoking in your uniform—it would reflect badly on the school.

Elvis was huge. The Kingston Trio, Bill Haley and His Comets. We knew every Johnny Mathis song because you could slow-dance to him. We got interested in John F. Kennedy in senior year because he was cute and Catholic. But there were a lot of Republicans. One of my friends was the daughter of Bill Miller, who was head of the Republican National Committee and ran as Barry Goldwater’s vice-presidential nominee.

The debate team was my big thing. We had a glee club and a liturgical choir. I worked on the paper and the yearbook. All the rivalries that exist now existed then. It was St. Albans/Friends, Gonzaga/Georgetown Prep. I dated one of the debaters from Gonzaga for a while.

I loved my friends, I loved my teachers and the spirit of togetherness. It was a wonderful experience.

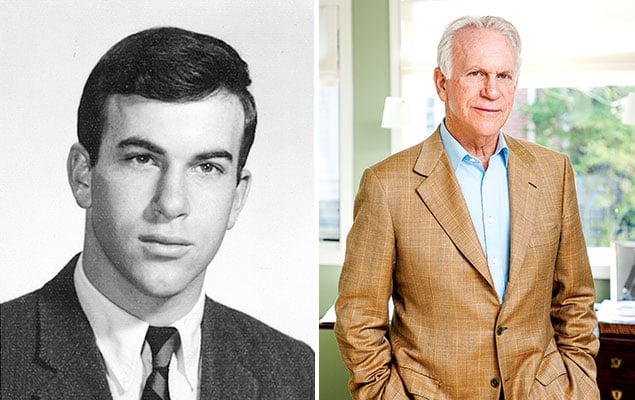

James K. Glassman

Sidwell Friends School, Class of 1965

Glassman is founding executive director of the George W. Bush Institute, a public-policy center in Dallas. He has spent time as a business writer, magazine publisher, TV news-show host, and undersecretary of State for public diplomacy. He lives in Bethesda.

A lot of students were the children of teachers and government bureaucrats. There was one place to go in Washington if you wanted cachet, and that was St. Albans and National Cathedral.

The one big negative was that we were the last segregated class at Sidwell Friends. I don’t know if black kids were specifically excluded, but there weren’t any.

After school, we would go to the Hot Shoppes drive-in restaurants. You’d walk around and see who was there and drive around. That was major entertainment.

When JFK was killed, I was a junior. I remember very clearly that I was in biology class. The big question was whether we would have a party or not on Saturday night and we did. I feel embarrassed about that, but we did.

People in my generation remember the Cuban missile crisis because we thought we were all going to die in a nuclear war. There was this feeling of helplessness. I had a friend whose family drove to Canada.

This article appears in the November 2013 issue of Washingtonian.