On a Sunday in early April, Scott Goodstein set off on a motorcycle tour of Maryland horse country with his cousin and a friend from political circles. They hadn’t gone far when, at 7:30 in the morning, a GMC Yukon pickup truck coming in the other direction caught the front tire of Goodstein’s Yamaha. In the spinout, his legs, nose, and right cheek were broken, his lung bruised, and ligaments ripped in his neck. A helicopter flew him to a Baltimore shock-trauma center, and Goodstein spent the remainder of the spring and most of the summer in one treatment facility or another.

The first blessing: He didn’t die. The second: Back in 2009, Revolution Messaging—the scrappy digital-marketing firm of which he’s CEO—had joined the fight for health-insurance reform on behalf of a client, Health Care for America Now. As a sign of its commitment, Revolution had equipped its employees with steel-plated health insurance.

“We don’t have 401(k)s; we don’t have pensions,” Goodstein says. “But we got really good health care.”

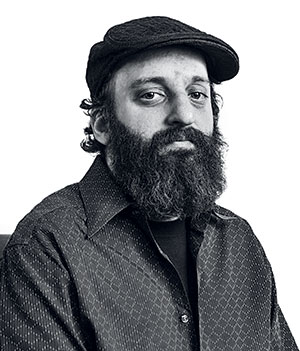

The accident added a “recovery beard” to Goodstein’s striking, old-soul looks—a fluffy black nimbus more suited to a member of the Boston Red Sox than to a Washington consultant. When we first met, not long before his encounter with the Yukon, Goodstein had put on what he called a “grown-up button-down” over his black T-shirt featuring the stylized bat logo of Alternative Tentacles, the record label of punk legend Jello Biafra.

A punk sensibility has fueled Goodstein’s career, first as a promoter in the record industry, then as a political campaigner for Barack Obama and other Democrats. Revolution Messaging is a model of punk tactics, recruiting outsiders to its causes, making a virtue of low budgets, and tempering outrage with high-minded principles.

“We don’t celebrate Columbus Day, because of how ruthless he was to the Arawak Indians,” Goodstein says. Instead, Revolution’s employees are off on May Day, the labor movement’s commemoration of an 1886 bombing at a workers’ rally in Chicago, known as the Haymarket Affair.

“If I get to write the rules,” he says, “why not?”

• • •

At the firm’s sixth-floor head-quarters south of DC’s Dupont Circle, Goodstein’s partners and their staff of two dozen or so coders, social-media analysts, and video editors study the nuances of today’s digital networks and deploy banner ads, viral Facebook posts, and a bounty of tweets. Revolution aims to exploit both the web’s precision targeting and its bottomless maw for content. If its messy, do-it-yourself spots sometimes look amateurish—in one campaign ad during the 2012 Virginia Senate race, the stout, five-foot-five Goodstein stood in for the lanky Republican candidate, George Allen—they can also make polished traditional political ads look like overkill.

“Stop playing softball,” read a Facebook ad that popped up on congressional aides’ news feeds during the Obamacare battle, “and tell your boss to pass health-care reform.”

Says Goodstein: “I can do that for a few thousand dollars or I can buy the Metro”—that is, saturate strategic stops like Capitol South—“for tens of thousands of dollars.”

Not everything Revolution produces hits its target or gets the company paid. When I visited this spring, I found a partner, Arun Chaudhary, a onetime Obama White House videographer, in a production room screening an ad intended for a 2012 online campaign, cooked up with the cocreator of The Daily Show With Jon Stewart. In every sense, it’s in-your-face: A plastic model of a uterus is flung smack into the visage of an actor playing Average American Politician.

“I showed it to the campaign,” says the mop-topped, scarf-wearing, and mildly manic Chaudhary, “and they were like, ‘This is why Bill Burton [a veteran Obama communications strategist] doesn’t return your phone calls.’ ”

Goodstein calls this approach “bulldogging crazy ideas,” few of which go to waste. During the recent federal-government shutdown, Revolution, acting on its own, put up a website called DrunkDialCongress.org, suggesting readers do just that to demand an intelligent budget. In the last presidential campaign cycle, Revolution ads that couldn’t find a client—in one, the private-equity firm Bain Capital is represented by a vulture—appeared on the website BuzzFeed in a piece headlined exclusive: 5 political ads that didn’t make the cut.

• • •

Misses aside, the moment for Goodstein’s methods seems to have arrived.

“Just about everything they’ve created for us has taken off,” says Nita Chaudhary (no relation to Arun), cofounder of the women’s-issues group UltraViolet. Last winter, as Ohioans debated a rape case involving small-town football players, Revolution shrink-wrapped a truck with a message telling the state’s attorney general, Mike DeWine: THE WORLD IS WATCHING STEUBENVILLE.

Goodstein’s ability to make a full-blown movement seem to have sprung from nowhere came to light in Obama’s first run for the White House, when Goodstein turned the emerging mesh of online social networks into campaign tools. He crafted profiles for Obama on MySpace, BlackPlanet, and Eventful. He constructed the candidate’s mobile program, which made history by announcing Joe Biden as running mate via text message.

The goal, says Merici Vinton, a digital strategist who worked on Goodstein’s team, was “to be in your lives 24 hours a day.” Every MySpace post or text message got a response from a staffer or volunteer.

“These aren’t people asking about the Iraq War,” Vinton says. “They’re texting, ‘What’s up?’ or ‘Hey, Barack, you’re really hot.’ We’d say, ‘Hey, thanks. Can you go and volunteer today?’ ”

Viewed from outside, the campaign appeared to be a people-powered project, and Illinois senator Barack Obama, a still dewy national figure, became part of the cultural fabric.

Goodstein also worked offline, arguing that the campaign should focus attention on local gathering spots such as barber and skate shops and gay bars, particularly in battleground states. “These are not conservative voters,” Goodstein says.

He trained canvassers “to stop thinking in a grid of precincts and start thinking culturally: Where’s the record store?” Often, he says, all it took for store owners to agree to put up an Obama window decal was “someone asking them.” After artist Shepard Fairey—whom Goodstein knew through friends who had used Fairey’s work on album covers—posted an image of the candidate, “I had all sorts of friends calling me,” Goodstein recalls, “saying, ‘Dude, did you know Shep Fairey is endorsing Obama?’ ”

The campaign asked Fairey to produce the blue-and-red screen prints that, besides being the most lasting visual imagery of the 2008 campaign, helped draw in the so-called creative class.

Some on the campaign saw Goodstein’s lifestyle politics as an unproven diversion of resources. “I got yelled at by Michelle Obama for creating ringtones: ‘Oh, my God, you’re turning him into a hip-hop star,’ ” Goodstein says. Jon Stewart devoted three full minutes of The Daily Show to deriding the push, declaring, “Novelty cell-phone rings are not going to get anyone elected President!” A Huffington Post headline deemed it the worst idea ever. “Meanwhile,” Goodstein says, “tens of thousands of people were joining the mobile program to download ringtones.”

“He’s one of the most unique people I’ve ever met,” Todd Thompson, a political organizer for the Teamsters, a Revolution client, says of Goodstein. “And I meet a lot of people.”

Thompson remembers him as one of the first people in politics to point out that “if you’re not communicating with people the way they want to be communicated with”—by telephone trees, texts, or Facebook—“then you’re not communicating with them.”

That’s a lesson many politicos still haven’t absorbed. In the 2012 race, Goodstein says, the Mitt Romney camp “lined up TV pundits instead of culturally digging in.”

The corollary is that all connections, digital or otherwise, need to be personal. “I learned it on U Street,” he says, “promoting shows by word of mouth, selling it on the street. I learned to talk to people.”

• • •

Goodstein arrived in Washington from Cleveland in 1992 to study government at American University—and to indulge his longstanding interest in DC’s music scene.

“I came to Washington for politics and punk rock,” Goodstein says. The District’s punk scene—anchored by bands like Bad Brains, Minor Threat, and Fugazi and the label Dischord Records—had an open, socially conscious vibe.

“In the punk-rock world,” Goodstein says, “it’s not a concert; it’s a show—meaning the guys on the stage are just one piece of it. The guy that makes the fanzine is a piece of it, too. The crowd singing along is a piece of it. The reality of punk rock isn’t about idolizing someone. It’s about pushing each other to evolve.”

He moved between music and politics, promoting bands at the Black Cat and barbacking at the 9:30 Club, dropping out of college briefly to help elect Oregon senator Ron Wyden to replace disgraced Oregon senator Bob Packwood.

Between college and campaign stints, Goodstein worked as a rep for Sony Music, assigned to the aggressive, “nu metal” band Korn. “My boss said to me, ‘You know what the number-one thing is in selling music? You buy music when your friends say it’s cool music.’ You needed skate shops and tattoo parlors saying that if you’re into anger, buy Korn. I hated that band, but I watched it work.”

By 2002, having earned his master’s in public administration at AU and worked local races in Iowa, Virginia, and New Jersey, he’d had enough of politics. “I literally threw my phone in the Mississippi River on the way out of Davenport, I think it was,” he says.

Goodstein came back to DC, where he teamed up with friends from the punk scene to focus on cultivating the progressive grassroots, leading groups such as PunkVoter and Rock Against Bush. He fought to keep the big event company Live Nation out of DC venues over worries that it would smother the local music scene, and he was spokesperson for the ultimately unsuccessful attempt to save New York City’s punk breeding ground, CBGB. In 2005, Goodstein helped organize a giant, ten-hour antiwar concert on the Mall headlined by Thievery Corporation.

In 2007, “pissed off about the wars,” he spent time drinking beer and talking with Obama’s principal digital strategist, Joe Rospars, who signed him up with the campaign. Friends in punk music and progressive politics thought Goodstein was selling out, but he told those who would listen about “the guy in Chicago who’s willing to speak truth to power.”

“We were the only two folks into punk rock in Team Obama, that’s for sure,” says Arun Chaudhary, who was new-media road director on the 2008 campaign, then became the first official White House videographer. After leaving government, Chaudhary bounced between Washington consulting firms that didn’t quite know what to do with him: “No one else in town can see me as a political communicator and a filmmaker.”

Goodstein offered Chaudhary a conference table to write his post-White House book, First Cameraman. Chaudhary ended up staying, joining analytics expert Keegan Goudiss and online fundraiser Tim Tagaris, who had made his reputation working on businessman Ned Lamont’s primary defeat of Joe Lieberman, the Democratic incumbent in Connecticut’s 2006 Senate race. (Lieberman won the general election after becoming an independent.)

Since Revolution opened its doors on July 4, 2009, it has booked as clients the Democratic National Committee, the 2-million-member Service Employees International Union, and the NAACP. What happens, I ask Goodstein, when his more mainstream customers hear Revolution’s hold music? Recently, I waited to the hammering guitar of Wayne Kramer—an antiwar, addiction, and prisoner activist—as his proto-punk band, MC5, railed: “Right now, right now, it’s time to kick out the jams, motherf—er.”

“We say, ‘Well, he is a client, too.’ ”

• • •

Revolution Messaging’s latest fight is shaping up as a generational battle between digital networking and the traditional grassroots organizing of the National Rifle Association—the start-up against the 142-year-old behemoth.

Less than a month after last December’s school shooting in Newtown, Connecticut, former Arizona congresswoman Gabby Giffords—herself the victim of a 2011 shooting outside Tucson—and her husband, Mark Kelly, launched Americans for Responsible Solutions, a super-PAC advocating for tighter regulation of gun ownership. Revolution, brought onboard by Tagaris, has helped set up the website, penned fundraising e-mails, crafted ads, and built a mailing list. But the strategy clearly includes an emotional appeal that trades on Giffords’s injuries and the steadfast presence of Kelly, a retired astronaut.

Not so long ago, Goodstein says, “you’d put 15,000 names on a black-and-white page and say, ‘You need to pass handgun legislation now. Sincerely, Some Impressive People.’ ”

Three weeks after Americans for Responsible Solutions launched, Giffords and Kelly testified on Capitol Hill. Shortly after their Senate testimony, a backstage video shot by Chaudhary appeared, showing the fresh-pressed lobbyists’ private moments. In one scene, Giffords brushes lint from the tail of Kelly’s suit as they prep in a hotel room. Later, a nervous Kelly drapes his arm over his wife’s shoulder. “Hello, internet people,” he says to the camera.

Giffords and Kelly’s foray failed to sway the senators, who voted down a gun-control bill in April. More recently, Colorado state legislators were recalled for supporting gun limits. But in the PAC’s first six months, it has raised $6.6 million, nearly half of which came from donors giving $200 or less—slightly under what the NRA pulled in over the same period, evidence that Goodstein may yet help rewrite the rules of the gun debate, as he did presidential electioneering.

There’s only one rule he’s been forced to follow. “I’m done with motorcycles,” he says. “My business partners had me sign off on that.”

This article appears in the December 2013 issue of Washingtonian.