About five years ago, C. Ray Foster, the sheriff of Buchanan

County, Virginia, noticed the name of an unfamiliar doctor on the pill

bottles turning up at drug busts, overdoses, and DUIs. OxyContin and other

narcotic painkillers feed an epidemic of crime and addiction as insidious

in this Appalachian outpost as the kudzu astride the Levisa Fork River.

But this prescriber’s name—Alen Salerian—was an enigma.

The man wasn’t a pain specialist but a psychiatrist, a doctor

trained to treat mental illness. And his office was 400 miles north, in

one of Washington’s wealthiest neighborhoods.

“I came out of there with 450 roxy 30s, 450 methadone 10s,

Adderall and Xanax,” someone calling himself “Crazy” wrote online about

his first visit to Salerian, the popular subject of nearly 500 posts in a

Buchanan County web forum. “My sister went the same day and got the same

thing. . . . At one time 5 of us rode together and he made our

appointments back to back . . . . I don’t know how in the world we made it

home we would be so messed up.”

The question Foster kept asking himself was why people in his

impoverished county were driving up to eight hours each way—sometimes in

caravans and carpools—to see a psychiatrist, one who didn’t even take

insurance.

Salerian’s colleagues back in Washington would have been just

as bewildered. Salerian, now 66, was once chief psychiatrist to the FBI’s

employee-assistance program, traveling the world to minister to troubled

agents. He taught at George Washington University, published in medical

journals, wrote op-eds for the Washington Post.

His private practice, steps from the Neiman Marcus in DC’s

Friendship Heights, was a world away from the troubles of Buchanan

(pronounced “buck-cannon”) County, a once-booming coalfield at Virginia’s

border with Kentucky and West Virginia that’s now one of the poorest and

most isolated places in the state.

To get there from Washington this past September, I drove for

hours down interstates 66 and 81, up through tunnels bored into mountains,

and over the Trail of the Lonesome Pine. Finally, the road tucked into

valleys so vertiginous that for much of the day the hills were shrouded in

shadow.

Sheriff Foster—a wry lawman with a silver mustache and a

reputation for candor—was at his desk, picking at a breakfast of biscuits

and gravy in a Styrofoam clamshell, when I entered. “I’m an old fat man,”

he quipped when asked his age.

But when I mentioned Salerian, Foster grew serious, turning off

the air conditioner and dialing up his hearing aid. Buchanan County

residents die of prescription-painkiller overdoses at more than five times

the statewide rate, and Foster held the psychiatrist at least partly

responsible. His pills had shown up at drug scenes across the county and

in the homes of families so lost to addiction that the state had to take

custody of children.

“I’ve never met him, but I’ve met a lot of his work,” Foster

said. “His clientele has become my clientele”—by which he meant denizens

of the county lockup.

The giant doses Salerian was prescribing to young, seemingly

healthy people in the county where Foster had grown up didn’t make sense.

“Why would a 20-year-old feller take five Oxys a day?” he asked. “Why

would you prescribe that to a 20-year-old that has not got cancer, has not

got no fatal disease, has got no chronic pain?”

• • •

A visitor to Alen Salerian’s office in the 1980s and ’90s would

have encountered one of the most glittering waiting rooms in Washington.

Middle Eastern royals, Hollywood actors, and heiresses were all under his

care, as were a general and a senator turned presidential candidate. Many

patients felt he was the first doctor to really understand their

suffering: “the one person I trusted,” local author Gail Griffith said in

a memoir.

Though just five-foot-seven, Salerian had a way of filling a

room. He was garrulous, with an exotic accent and boisterous charm, and he

loved the limelight. He had wrangled a gig as an on-air commentator for

Channel 9, Washington’s CBS affiliate, and was sought out for his

expertise by TV programs such as 48 Hours.

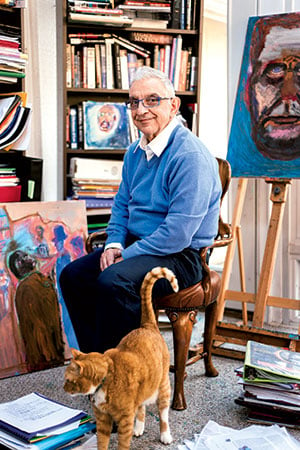

once held a glamorous post with the US government, counseling FBI

agents. Today the government alleges that Salerian (shown at home in

Bethesda) is a major supplier of pills to drug addicts and dealers in

southwestern Virginia. Photograph by Andrew Propp.

It was a remarkable ascent for a man who’d landed in the US

from Istanbul in 1971 with no connections beyond a letter admitting him to

a medical internship. Salerian’s father, a successful engineer, and

mother, a noted painter, had sent him and his identical-twin brother to

America because they saw no future for Christian Armenians like them in

Turkey. Alen’s brother, Nansen Saleri, now a Houston oil executive, calls

himself the ace student and “conformist one.” Alen was more like his

mother, a social butterfly with artistic impulses who sometimes skipped

school to be with friends.

No one was surprised when he declared an interest in

psychiatry. “He wanted to be around people,” Nansen says; among all the

medical specialties, “it would allow him more of an emotional relationship

with patients.”

Salerian’s supervisors at George Washington University, where

he completed his psychiatry training, named Salerian chief resident and

hired him as an assistant clinical professor right after his training

ended in 1976. He was no less a hit at Metropolitan Psychiatric Group, one

of the nation’s largest group mental-health practices. Salerian drew so

much business to its DC and Rockville offices that the group made him

partner after just two years.

Soon after a Pennsylvania company acquired the group in 1994,

Salerian took a $1.5-million payout and started his own practice on the

ground floor of the Psychiatric Institute of Washington, a Wisconsin

Avenue hospital that eventually named him associate medical

director.

It was a heady time. Pharmaceutical companies were so taken by

the doctor’s social dexterity that they paid him tens of thousands of

dollars a year to host dinners introducing colleagues to new drugs. He’d

also landed a glamorous five-year contract with the FBI’s

employee-assistance program, which wanted him to find help for agents

wrestling with alcoholism, family strife, and other personal

issues.

Salerian, a married father of four, had always liked difficult

cases: patients whose depression responded to none of the usual

treatments, manic-depressives who’d sooner live on the streets than take

their meds. At the FBI, he cracked his toughest case yet: getting hardened

agents to confide in a shrink.

Chuck McCormick, a former FBI agent who led the assistance

program in the 1990s, says he could call day or night and Salerian would

get on the next plane to anywhere in the world—domestic FBI offices,

overseas embassies. “We saved lives, salvaged careers,” McCormick says.

“We kept families together. We prevented divorces. He was a

godsend.”

A few years into the contract, however, Salerian had a

falling-out with the agency over what he construed as a supervisor’s

racist remark about his olive-toned skin. “I used every F-word,” Salerian

recalls of his response. McCormick says he remembers no such incident. All

the same, the bureau decided to shift its program in-house after

Salerian’s contract was up in 1997—a parting that would come to haunt the

FBI and the doctor both.

• • •

In February 2001, a veteran FBI spy catcher, Robert Hanssen,

was arrested in the gravest security breach in the bureau’s history: The

mild-seeming Virginia man, it turned out, was a double agent who had been

selling US secrets to the Russians for more than two decades.

In his former employer’s humiliation, Salerian glimpsed

opportunity. He had been trying for years to write opinion pieces for

major newspapers, with scant success (despite the help of publicists).

Three weeks after Hanssen’s arrest, Salerian got his big break: The

Post published his long op-ed flogging the FBI for not subjecting

agents to routine mental-health checks.

The piece read like a John Grisham thriller, with Salerian as

its dashing lead, a troubleshooter who’d saved the agency from untold

numbers of overstressed G-men who might well have become other

Hanssens.

He made no mention of his falling-out with the FBI. Nor did he

disclose that he was just then auditioning for a starring role with

Hanssen’s defense team.

Salerian had recently offered his services to Plato Cacheris,

Hanssen’s court-appointed lawyer. Cacheris was the go-to attorney for

defendants in the inner circles of Washington power: Aldrich Ames, Monica

Lewinsky, and John Mitchell, of Watergate notoriety, had all been

clients.

Cacheris hadn’t envisioned a psychiatric defense. “On the other

hand,” he says, “if a psychiatrist could say something helpful, if not

exonerating, we might need it.

“I figured if the FBI used him, he must be okay.”

Over the course of seven jailhouse meetings, Salerian got

Hanssen, a shy and socially awkward man, to confide his most humiliating

personal secrets: his father’s physical abuse, his sexual obsessions, the

hidden camera Hanssen had installed in the bedroom he shared with his wife

so a friend could watch their lovemaking.

Privacy laws and professional ethics hold both lawyers and

doctors to strict client/patient confidentiality. Federal rules for

high-risk detainees like Hanssen set an even higher bar: Disclosures to

possible witnesses or codefendants, such as a suspect’s wife, are

verboten. Yet despite Cacheris’s explicit orders, Salerian went to

Hanssen’s wife, Bonnie, with details of her husband’s betrayals, then

lobbied her for permission to speak to the press.

When she refused, Salerian did it anyway, telling BBC reporters

about his jailhouse conversations with Hanssen. He even offered to take a

photo of Hanssen to sell to the media.

Shocked, Cacheris summoned Salerian to his office in May 2001

and fired him. He warned the doctor to say no more to anyone about the

case. His client, after all, was facing the death penalty.

But Salerian had other priorities.

Over the next few months, he gave on-the-record interviews to

CBS News, the Post, the Sunday Times of London, and many

others. He portrayed himself as a prophetic doctor who could have seen the

warning signs the FBI and the Catholic Church had missed (Hanssen had

confessed to a priest) and who owed America the truth.

“His espionage was an escape from his sexual demons,” Salerian

told Lesley Stahl on 60 Minutes. “When he found himself in

exciting and dangerous positions, such as espionage and spying, he found

that his demons slowed down, they calmed down.”

Salerian sold the option rights to his story to author Norman

Mailer and film producer Lawrence Schiller, who took him to a boozy dinner

at Old Angler’s Inn in Potomac. Though they never portrayed him in their

book and TV movie about Hanssen, the voluble doctor appears to have held

nothing back: Mailer’s interview transcripts with Salerian span some 500

pages.

When the rare reporter questioned whether Salerian’s dismissal

from the defense affected his credibility, the doctor suggested he

answered to a higher code: He knew better than the lawyers or the

guardians of medical ethics what was good for Hanssen and society. “I have

100-percent moral and psychological authority,” Salerian said.

Others saw another motive. Cacheris had decided to seek a plea

deal sparing Hanssen’s life, and for Salerian that meant one thing: no

chance to be the star expert in a trial with headlines the world over. “He

told people he was hoping I wouldn’t settle the case and deprive him of

the opportunity” to testify, Cacheris says.

Weeks after a plea deal was reached, Salerian argued that the

opprobrium heaped on him by fellow psychiatrists proved that it was

they—not he—who had failed the mentally ill. “The biases against

psychiatric disorders and mental illnesses will only go away if we

confront them,” he wrote in USA Today. “So far, no one is brave

enough to go up against them—not the church, not the FBI, not even the

mental health profession itself.”

No one, that is, but him.

Many colleagues struggled to square the brazenness of

Salerian’s conduct with the thoughtful physician they thought they knew.

But clues to another side of the doctor—explosive, attention-craving,

defiant—were hidden in plain sight.

In his first year as a resident at GW, Salerian openly mocked a

renowned expert on narcissism, who later bristled to the program director,

“Where do you get your residents?”

At the Metropolitan Psychiatric Group, Salerian needled what he

called his “lily-white colleagues” by treating psychotics, schizophrenics,

blacks, and the poor—people who deviated from the stock clientele of

affluent women suffering what he dismissively dubbed “Bethesda Wife

Syndrome.”

The board exams in psychiatry are a mark of professional

distinction. But Salerian failed them and never tried again: “I began

disagreeing with psychiatry,” at least as currently practiced, he says.

“It slowly began occurring to me how different my thinking

was.”

Salerian saw his reputation for controversy as the calling card

of an original mind. He sought patients whom other colleagues couldn’t

handle or wouldn’t touch, then gave them treatments other doctors

wouldn’t. In the 1980s and early ’90s, when most psychiatrists were still

analyzing patients on couches, he began prescribing newly approved drugs

in unorthodox combinations, in search of experimental, “off label”

treatments, sometimes for conditions outside his field.

His willingness, even eagerness, to prescribe exotic drug

cocktails endeared him to many patients, particularly those in the grips

of despair. A Chevy Chase woman whose brother is bipolar says they’d

visited specialists in DC and New York before a doctor referred them to

Salerian in 2000. For years, her brother refused pills that doctors said

he needed to get better. Salerian was the first to break through. He

patiently explained how the brain worked, never charging for the extra

time, and drew sketches showing how pills helped. “From our family’s

perspective,” she says, “Dr. Salerian saved a life.”

But his pharmaceutical cocktails made even his admirers

nervous. “They were very unusual combinations of medications,” says Carl

Gray, a Rockville psychiatrist who sent Salerian some of his toughest

patients.

Laurence Greenwood, a psychiatrist in Prince George’s County,

remembers seeking out Salerian for advice about a relative with

intractable schizophrenia. Salerian suggested the stimulant Ritalin, an

ADHD drug traditionally thought to aggravate psychosis. The relative’s

doctor balked: He wasn’t comfortable turning his patient into a test

subject. “Nor would I have been as a doctor, because as a doctor I’m being

cautious,” Greenwood says. “But as a patient, a family member, where the

quality of life of a whole family is being severely disturbed by the

patient’s suffering, it would be a very reasonable thing to try. In a

sense, I wish I had Alen’s courage.”

Bernard Vittone, who directs a prominent mental-health clinic

in DC’s Foggy Bottom and has known Salerian for decades, puts it another

way: “He has some traits you could view as being admirable or very

reckless.”

• • •

After the Hanssen affair, George Washington University cut

Salerian loose and the Psychiatric Institute declined to renew his

hospital privileges. He and the drug companies whose pills he promoted

parted ways.

The Maryland medical board issued an excoriating ruling that

accused Salerian of “gross” ethics violations in the Hanssen case. The

doctor, the board wrote, seemed to have “a perception of self so grandiose

as to raise concerns about his judgment.” Remarkably, the Maryland and DC

medical boards let Salerian off with a reprimand and fines of just

$8,500.

The ruling barely broke his stride. Salerian remained a regular

on Channel 9 and kept up a busy practice, where patients who remembered

his TV appearances now felt they were in the hands of a highly

sought-after psychiatrist.

But things were getting strange. In 2003, Salerian

self-published a glossy book of cartoons called Honest Moments With

Dr. Shrink. Though pitched as a satire of psychiatry, the

cartoons—pastel-crayon doodles that call to mind a grade-school art

fair—were at best cryptic, at worst racially charged and sexually vulgar.

“Doc, please help me find my G spot,” a woman shaped like an eel says on

the first page. “Who saw it last?” says Dr. Shrink, who’s drawn in the

shape of a refrigerator.

Honest Moments was followed by a Salerian line of

vitamins. Then came a deepening preoccupation with John F. Kennedy’s

assassination, research trips to Dealey Plaza, and a torrent of more than

200 JFK-inspired paintings that he exhibited in Dallas and DC.

Salerian found another canvas for his creative impulses on the

lawn outside his office. Pronouncing the landlord’s landscaping “bland,”

he turned the empty sod into a statue garden, complete with a rooster

figurine, a fountain ringed by 24 lion heads, and a giraffe he named after

his son Justin. He told the Washington City Paper at the time

that the installation was a whimsical welcome mat meant to “make

neuropsychiatry accessible.”

Inside Salerian’s office, however, some longtime patients felt

unsettled. A Maryland woman recalled her unease when a large oil painting

depicting a nude couple in the throes of coitus went up in the waiting

room. Once-brisk appointments turned into drawn-out bull sessions about

the doctor’s art and his latest JFK findings. “When you went to see Dr.

Salerian, you took the whole day off,” one patient says.

The most extraordinary shifts were inside the exam room. A

growing number of patients were traveling great distances for another new

sideline: addictive narcotic painkillers such as OxyContin, methadone, and

Fentanyl.

The doctor appears to have embraced the drugs soon after

Cacheris fired him from the Hanssen case and just as the first major news

stories about OxyContin’s dark side broke. The pill, approved by the Food

and Drug Administration in 1995, was the first made of pure oxycodone, a

powerful derivative of the opium poppy. It was formulated to dissolve in

the body over 12 hours, but people found they could ingest the oxycodone

all at once by crushing the pill and then snorting or injecting it. The

euphoria gave the drug street value and the nickname “hillbilly

heroin.”

Narcotic painkillers, typically prescribed to cancer patients

and others in severe physical pain, have no FDA-approved psychiatric uses.

But Salerian wanted to blaze a new frontier. “I have prescribed OxyContin

to more than 200 of my patients, and none of them has become addicted,” he

boasted in a 2002 op-ed in the Indianapolis Star. He said he’d

used the drugs to treat not just physical pain but also

depression.

It had been at least a half century since doctors had tried

anything of the kind. Though physicians in the 1800s had given opium

derivatives such as morphine to people with “melancholia” and other

ailments, by the 1950s scientists had produced the first class of modern

antidepressants. They were more effective and had fewer side effects than

opiates and were not addictive. To tout opiates for depression now would

be somewhat like prescribing arsenic and mercury for syphilis, decades

after the invention of penicillin.

• • •

Salerian’s faith in the power of painkillers springs from

something he calls the Salerian Theory of Brain. This “new paradigm,” he

wrote in a non-peer-reviewed medical journal, would do to the foundations

of modern psychiatry what Galileo did to “Ptolemaic assumptions about the

celestial movements.”

The theory’s narcotics bit goes something like this:

Endorphins, our bodies’ natural opiates, are necessary for healthy brain

chemistry and good mood. People with too few endorphins—a group that in

Salerian’s view includes drug addicts—can get right, he believes, by

taking super-sized doses of manmade opiates like OxyContin.

As his colleague Bernard Vittone put it, Salerian was

“operating in universes I’ve never even seen.”

Yet the doctor had nearly absolute faith in his patients.

Though he often prescribed OxyContin at three times the recommended doses,

he refused to subject patients to common safeguards against abuse and

dealing. “Any doctor who creates these monkey, Mickey Mouse forms and

forces you to give drug urines,” he told an internet radio show, “is

actually raping Hippocrates.”

The test subject for his opiate cure, Salerian says, was a

severely depressed, drug-addicted railroad worker named Paul. Over a

series of hospitalizations in the mid-1980s, Salerian used conventional

methods to wean Paul off an addiction to Fiorinal, a non-opioid painkiller

and muscle relaxant.

But in the 1990s, after traditional depression treatments

failed, Salerian says he ceded to Paul’s request for Percocet, a narcotic

painkiller. Salerian rhapsodized about the results. Though forced into a

disability retirement, Paul discovered true pleasure in a new car and in

vacations with his wife, Salerian insists. (Paul’s wife disputes

Salerian’s account.) All the same, in the spring of 2001, Salerian added

another pill to Paul’s drug cocktail: OxyContin. The next year, another:

Fiorinal, the very drug Salerian had detoxed Paul from a decade and a half

earlier. Paul grew addicted again, this time to the active ingredient in

OxyContin. In 2004, his wife filed a complaint with the DC medical board

about Salerian’s narcotics experiments, but it didn’t do her any good. She

became a widow in 2005, when Paul bled to death from an undiagnosed

intestinal ulcer.

Four years later, in January 2009, the DC medical board said

there wasn’t sufficient evidence of misconduct and dismissed the case.

Salerian, who spent $750,000 on an elaborate defense, says he took the

ruling as both exoneration and endorsement. He changed the name of his

practice to the Salerian Center for Neuroscience and Pain and felt that

his scientific revolution was finally under way. “It was a dream,” he said

later. “My march began.”

By February 2010, another patient was dead.

Patrick Kennedy—or Paddy, as his family called him—was a quiet

but playful kid who began taking illegal drugs his sophomore year at

Bethesda–Chevy Chase High School. In college he grew depressed and worried

he might be succumbing, as had his mother, to schizophrenia.

His elder brother took Paddy, then 20, to see Salerian, with

whom their family had had good experiences in the past. Salerian gave

Paddy an on-the-spot diagnosis of obsessive-compulsive disorder,

attention-deficit disorder, and phobia—and a prescription for methadone, a

narcotic approved only for chronic physical pain and for heroin

maintenance and detox therapy.

Because it can slow breathing, the medical rule of thumb for

methadone is start low, go slow. Salerian wrote Paddy a dose above the

manufacturer’s guidelines, believing it would boost his dopamine, a

neurotransmitter that helps regulate motivation and

pleasure-seeking.

The day he took his first pill, Paddy sent his family an

effusive e-mail. “Dr. Salerian has given me new hope,” he

wrote.

Two days later, his father, Steven Kennedy, an editorial

consultant, cooked a dinner of beef-and-barley soup and settled onto the

couch with his son for an episode of House, the TV drama about a

drug-addled doctor with a genius for diagnosis. Before the show was over,

Paddy complained about his vision. “My eyes feel out of focus, Dad,” he

said and went to bed.

When Paddy was still in bed at 11 the next morning, his father

went in and found his son’s body pale and rigid. Blood had pooled in

purple blotches under his skin, a sign he’d probably been dead for hours.

Detectives counted the remaining methadone pills: There was no indication

he’d taken more than prescribed. The Virginia medical examiner ruled the

death an accidental overdose.

On the morning of March 3, 2011, teams of gun-toting DEA agents

in black jumpsuits raided Salerian’s home. They handcuffed Salerian’s wife

and the two adult children at home. (His wife told me she was so

traumatized that she soiled herself.) Salerian arrived at his practice to

find it commandeered by agents, who spent the day searching his computers,

files, and financial records. Under civil-forfeiture laws, which don’t

require criminal charges, the agents also seized three cars and the cash

in three bank accounts.

Salerian responded by appointing himself leader of a global

movement to end discrimination against pain sufferers. The curtain raiser

was to be a giant civil-rights-style demonstration—Festival Pain Brain—in

the fall of 2011 at the Lincoln Memorial. Salerian hired an advertising

firm to mount a publicity campaign and to e-mail invitations to 40,000

medical students. He promised a guest appearance by country star Blake

Shelton, an onslaught of 20,000 protesters, and the freeing of thousands

of butterflies. Actual turnout: perhaps two to three dozen. There was no

Shelton (who’d never agreed to come). There weren’t even

butterflies.

Convinced of sabotage, Salerian made a defiant trip three

months later to southwestern Virginia, where he’d heard that his

long-distance patients were being harassed by police. He had persuaded a

Buchanan County newspaper, the Voice, to host a public forum to

take on critics. The paper’s publisher, Earl Cole, told me the issue was

personal: His painkiller-addicted son had committed suicide in 2007, and

his 21-year-old grandson was high on pills a year later when he lost

control of his car and died in a head-on crash with a

tractor-trailer.

“I said, ‘You have a lot to do to convince me that you’re not a

drug dealer,’ ” Cole recalls. “But he did convince me. When he showed me a

picture of the brain and how it all worked, I began getting an open mind

about it.”

Cole remembers Salerian telling him, “I’m going to win a Nobel

Prize for this.”

As the months passed, Salerian’s waiting room saw fewer

patients in Rolexes and designer suits and more who looked like extras in

some modern Grapes of Wrath: coal dust under fingernails, hats

bearing Confederate flags. According to court papers, other tenants were

soon complaining to the landlord about “the traffic of dirty unkempt

people.”

Veteran staff bolted, and his office became a kind of hall of

mirrors. Salerian hired one of his sons as a clinical director and another

as a medical technician. He rated patients on a Salerian Pain Score,

Salerian Mood Score, and Salerian Attention Measure. Though people came to

him for physical pain as well as emotional distress, “there wasn’t a

blood-pressure cuff or a stethoscope in the entire office,” a former

employee says.

Salerian hired a bodyguard and, according to court records,

ordered a strip search of a patient he thought was a police informant. By

2012, his fee for an initial “pain management” consultation had risen to

$1,200, from $350 in 2010.

The front-desk staff soon asked patients to sign a new form. “I

am not an undercover agent,” it began, before warning that anyone who

tattled to authorities risked “serious consequences to [their]

health.”

• • •

Seven hours to the south and west, Sheriff C. Ray Foster and

Buchanan County’s chief prosecutor, Tamara Neo—along with state and

federal law-enforcement officials—were building what they hoped would be a

bulletproof criminal case.

A police informant showed up at Salerian’s office with a

healthy MRI and records from a previous doctor who thought he needed

nothing more than over-the-counter painkillers and exercise; the informant

walked out with a prescription for 210 tablets of oxycodone, 90 of

methadone, and 90 of Adderall, a stimulant, according to court records.

The next month, when he wanted refills, the informant didn’t even have to

come in. A request was phoned in to the office, and two days later UPS

delivered the prescriptions to the informant’s doorstep in southwestern

Virginia, in an envelope bearing the slogan “The Art and Science of

Healing.”

The DEA, meanwhile, heard from a Rockville pharmacist who’d

stopped filling Salerian’s prescriptions. The final straw for the

pharmacist was the parade of patients with Tennessee ID cards who visited

five minutes apart, each bearing a Salerian script written the same

day.

Investigators discovered that Salerian had been prescribing

more than 800 pills a month to four members of a major western Virginia

drug-trafficking ring, according to court records. There was also a

Buchanan County man, Brian Justice, who “was working with his mother,

apparently, and his sister,” a prosecutor said at a hearing. “Other people

were engaged to go as girlfriends down to see the doctor, and they were

actively recruiting—this was a thriving business, sort of like Mary

Kay.”

Last April, a federal grand jury in southwestern Virginia

indicted Salerian on 36 felony drug counts. Two months later, it added

over 100 more. The doctor now faces one count of conspiring to unlawfully

distribute controlled substances and 143 for unlawful distribution—in many

instances, to people in and around Buchanan County. If convicted at a

trial set to begin February 10, Salerian could spend the rest of his life

in prison.

The end can’t come soon enough for police in southwestern

Virginia. In Sheriff Foster’s office last summer, I asked two of his

plainclothes drug investigators where Salerian had ranked among doctors

writing scripts to county residents. “Number one,” came the reply. “The

majority of the medication coming into this county was written by

him.”

Salerian denies any wrongdoing. His lawyers paint him as a

pioneering pharmacologist whose clinic bore no signs of a profiteering

pill mill. “Unlike other doctors actually convicted of similar charges,”

they wrote in a statement, “Dr. Salerian established a doctor-patient

relationship with each of his patients. He did not receive kickbacks in

exchange for prescribing medication. He never led an extravagant

lifestyle. He never treated phantom patients.”

For Salerian, though, the ultimate indignity came in June of

last year, when the DC medical board finally acted. The board, composed

mostly of fellow doctors, voted unanimously to revoke Salerian’s medical

license. Salerian, trailed by his family, stormed out of the hearing room.

One of his sons wiped away tears.

I walked out with Paddy’s father, Steven Kennedy. On the plaza

outside the health department, Salerian, shaking with rage, pointed at

Kennedy. “Child molester!” he bellowed. “Child molester!”

As bystanders looked on stunned, Salerian’s family tried to

move him away. But he wouldn’t back down. “Child molester is here!”

Salerian sputtered. Finally, one of his sons managed to lead him up the

steps to North Capitol Street.

I caught up and asked Salerian for a response to his

professional defrocking. “The Vatican was unanimous when they said the

world was flat,” Salerian said. “Remember Galileo.”

• • •

Alen Salerian lives with his wife on a wooded lot in Bethesda.

I visited a week before he lost his license, and he answered the door

unsmilingly, with the darting eyes of a hunted man.

He’s free on $100,000 bond until his trial. But a judge

confiscated his passport and restricted his travel to Maryland and DC.

Salerian has filed for personal bankruptcy and owes his twin brother at

least $1.9 million, much of it for legal fees. In addition to preparing

his defense, his lawyers are fighting to reinstate his medical license.

Experts they’ve hired will argue that something other than methadone

killed Paddy Kennedy.

In the first minutes of our four-hour interview, I felt as if I

were listening to the raw neural firings of a persecuted man, the ravings

that jangle in our brains but that we dare not give voice for fear of

being seen as unhinged. There were disjointed references to “the laws of

the universe and the jungle,” “computers and nuclear bombs,” and

“devastation with trickery.” The shelves of a sunroom that had become his

makeshift office were lined with conspiracy books: Plausible Denial,

Rush to Judgment, Lessons in Disaster.

Salerian told me that a former employee whose depression he’d

treated with narcotics had family in Buchanan County, and that’s how

people there discovered his practice. Prosecutors, he said, were reading

too much into the distance patients had traveled and the spike in his

fees. He charged many people on a sliding scale. There was no mystery to

his popularity: Southwestern Virginia is home to many “poor, uneducated”

people in injury-prone jobs like mining and trucking. Overzealous DEA

crackdowns, Salerian said, had deterred all but the noblest doctors from

prescribing the painkillers patients desperately needed.

Some of Salerian’s friends and longtime patients told me they

worried Salerian had himself succumbed to dangerously “narcissistic” and

“grandiose” delusions. The doctor needed professional help, they said, not

prison.

When he and I spoke again last fall, I asked if it was possible

he was ill.

Salerian told me he’d been diagnosed in the 1980s with anxiety

and ADHD, for which his psychiatrist still prescribes Prozac and Adderall.

But he rejects the idea, proposed to him by colleagues over the years,

that he also suffers from bipolar disorder, a more serious condition in

which people sometimes feel possessed of a kind of superhuman

invincibility. He said his colleagues, forgivably, had mistaken his

prodigious work habits, theatrical personality, and wide-ranging artistic

pursuits for a disorder.

“Show me another psychiatrist who has had the record I have,”

he said.

Contributing editor Ariel Sabar’s new book is a Kindle Single, The Outsider, about a maverick psychology professor who turned the town of Oskaloosa, Kansas, into an observatory of human behavior. This article appears in the February 2014 issue of Washingtonian.