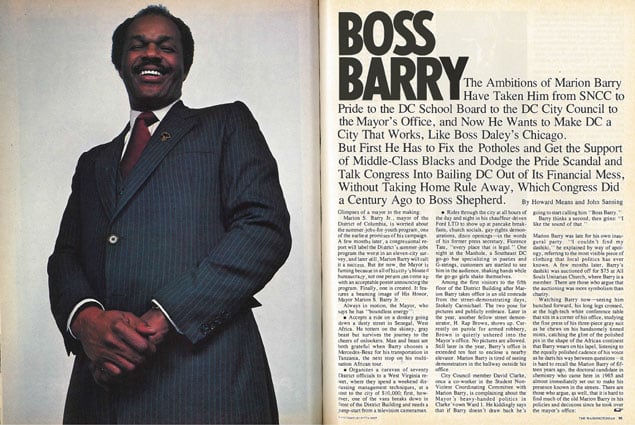

Glimpses of a mayor in the making:

Marion S. Barry Jr., mayor of the District of Columbia, is worried about the summer-jobs-for-youth program, one of the earliest promises of his campaign. A few months later, a congressional report will label the District’s summer-jobs program the worst in an eleven-city survey, and later still, Marion Barry will call it a success. But for now, the Mayor is fuming because in all of his city’s bloated bureaucracy, not one person can come up with an acceptable poster announcing the program. Finally, one is created. It features a beaming image of His Honor, Mayor Marion S. Barry Jr. Always in motion, the Mayor, who says he has “boundless energy”:

• Accepts a ride on a donkey going down a dusty street in Senegal, West Africa. He totters on the skinny, gray beast but survives the journey to the cheers of onlookers. Man and beast are both grateful when Barry chooses a Mercedes-Benz for his transportation in Tanzania, the next stop on his multination African tour.

• Organizes a caravan of seventy District officials to a West Virginia resort, where they spend a weekend discussing management techniques, at a cost to the city of $10,000; first, however, one of the vans breaks down in front of the District Building and needs a jump-start from a television cameraman.

• Rides through the city at all hours of the day and night in his chauffeur-driven Ford LTD to show up at pancake breakfasts, church socials, gay-rights demonstrations, disco openings—in the words of his former press secretary, Florence Tate, “every place that is legal.” One night at the Manhole, a Southeast DC go-go bar specializing in pasties and G-strings, customers are startled to see him in the audience, shaking hands while the go-go girls shake themselves.

Among the first visitors to the fifth floor of the District Building after Marion Barry takes office is an old comrade from the street-demonstrating days, Stokely Carmichael. The two pose for pictures and publicly embrace. Later in the year, another fellow street demonstrator, H. Rap Brown, shows up. Currently on parole for armed robbery, Brown is quietly ushered into the Mayor’s office. No pictures are allowed. Still later in the year, Barry’s office is extended ten feet to enclose a nearby elevator. Marion Barry is tired of seeing demonstrators in the hallway outside his office.

City Council member David Clarke, once a co-worker in the Student NonViolent Coordinating Committee with Marion Barry, is complaining about the Mayor ‘s heavy-handed politics in Clarke’s own Ward 1. He kiddingly says that if Barry doesn’t draw back he’s going to start calling him “Boss Barry.”

Barry thinks a second, then grins: “I like the sound of that.”

• • •

Marion Barry was late for his own inaugural party. “I couldn’t find my dashiki,” he explained by way of apology, referring to the most visible piece of clothing that local politics has ever known. A few months later, Barry’s dashiki was auctioned off for $75 at All Souls Unitarian Church, where Barry is a member. There are those who argue that the auctioning was more symbolism than charity.

Watching Barry now- seeing him hunched forward, his long legs crossed, at the high-tech white conference table that sits in a corner of his office, studying the fine press of his three-piece gray suit as he chews on his handsomely tinned mints, catching the glint of the polished pin in the shape of the African continent that Barry wears on his lapel, listening to the equally polished cadence of his voice as he darts his way between questions—it is hard to recall the Marion Barry of fifteen years ago, the doctoral candidate in chemistry who came here in 1965 and almost immediately set out to make his presence known in the streets. There are those who argue, as well, that it is hard to find much of the old Marion Barry in his policies and decisions since he took over the mayor’s office:

• Mayor Barry, the former SNCC president and veteran demonstrator, banned student street demonstrations at the height of the Iranian hostage protests.

• Mayor Barry, the former executive director of Pride Inc. and veteran user of federal money for the poor, accepted limitations on federally funded abortions, making it harder for the poor to obtain them.

• Mayor Barry, the former president of the DC School Board and longtime advocate of quality public education, demanded school closings, a reduction in the teacher force, and severe cuts in the operating budget.

• Mayor Barry, the former finance chairman of the DC City Council, informed the Council that budget decisions and financing choices were out of its jurisdiction.

Cynics would say such reversals of form are symptomatic of a purely political animal lacking a true ideological commitment; realists see them as affirmation that along with Marion Barry’s acquisition of power has come an awareness of its limitations. The rhetoric of the street does not translate easily into actions in office, and Marion Barry would not be the first ideologue to attain power and find himself unable to be faithful to his past—a lesson learned by people as diverse as Joan Claybrook of the National Highway Safety Administration and Ronald Reagan as governor of California.

If there has still been time for symbols in Marion Barry’s administration, if there has still been time for posturing, there has at least come an awareness that wishing will not make the District’s problems go away.

• • •

The “S” at the middle of Marion Barry’s name stands for Shepilovk.

“It happened back in the days when I was in college,’ ‘ says the Mayor. ”There was a fad going around where you used your first initial, then your middle and last names. I had a friend whose name was George Washington Cox, and he was saying that he was G. Washington Cox. I didn’t have a middle name, so I went and got one out of the newspapers some where in the Iibrary.” M. Shepilovk Barry, known as “Shep.”

Like the Mayor’s middle name with its resonances of crazed Bolsheviks, the city that he directs is in many ways a fabrication, a patchwork territory beholden to many masters—a governmental sleight of hand that on the one hand places Marion Barry beneath a wonderful medallioned ceiling in a cavernous office, and on the other gives him, he says, very little power to do anything lasting.

“The city is just not governable,” Barry says, “because there’s no way you can really have true control over the government.

That does not mean that the city’s not manageable. I can manage the resources that we have; I can manage the people and the money within what we have. But governing would mean having the right to make major decisions without having to ask somebody else if you can, and I can’t do that.”

This distinction between governance and management creates the Mayor’s first line of defense, and as the public becomes more and more aware of the depth of the District’s financial hole, he needs every line of defense he can get.

• • •

Conventional wisdom—and the Mayor is quick to recite it—holds that the sources of the District’s fiscal maladies are the tight-fistedness of the city’s chief property holder and employer, the federal government, which controls more than fifty percent of the District’s land; the byzantine budgeting procedures that flow from Congress’s control of DC’s purse strings; and the divided nature of the District government. None of this, Barry insists, is of his own making.

“I didn’t create all this,” he says. “It’s the result of years of accumulation. The chickens are now coming home to roost. But I have a responsibility to solve it.”

Barry is fond of pointing out that, although the District’s budget has risen 58 percent over the past five years, the federal payment to the city has in fact steadily declined as a percentage of the whole, now standing at $238 million or 17 percent of total city revenues. He argues that the federal payment should equal at least 50 percent of locally raised revenues to reflect the extent of the government’s tax-exempt land holdings here. It is an argument that Congress has never bought, and is even less likely to buy now that aid to cities of all sorts is on the brink of being cut back severely.

Barry argues as well that the solution to the District’s Alice-in-Wonderland finances is full budget autonomy , freedom from federal line-by-line analysis, tentatively set for 1981 but now, according to several congressional sources, in serious jeopardy. And even if it does come on schedule, an autonomy that carries with it neither a fixed formula for federal payments, nor reciprocal tax agreements with Maryland and Virginia, is not much autonomy at all.

Perhaps the most compelling item in Barry’s defense—one that the Mayor has come back to time and again in recent months, seeking to exonerate both himself and the city— is that the District is forced to bear multiple burdens by its role as a county and state government as well as a municipal one. The District not only picks up garbage and fills potholes like any other major city, but also provides omnibus health-care facilities such as DC General Hospital, which elsewhere are often funded partially or totally by county funds. Like a state, the District also collects income taxes, dispenses automobile registrations, incarcerates long-term prisoners, and provides unemployment compensation.

Thus, the District pays more of its own funds per capita for public education than any other large city in America, $482 in 1976-77 when the Census Bureau last made such comparisons. This was $130 more than New York City spent, $60 more than Boston, forty times more than Detroit, where different funding formulas provide for a much greater hare of state aid. Police protection in DC costs more than twice that of its nearest rival among major cities on a per-capita basis. Per-capita health and hospital costs are more than twice those of Baltimore, nearly ten times those of Chicago; the District’s per-capita expenditures of local funds for public welfare are exceeded only by those of New York City, are sixty times those of Boston, and eight hundred times those of Detroit, where the state of Michigan again picks up the vast bulk of the welfare tab. The District has more municipal workers per capita than any of its peers, more than twice the rate of San Francisco, nearly six times that of Minneapolis, five times that of Milwaukee.

Excess is inevitable with a work force so large that there is one city employee for every fifteen residents. Even Barry admits this, but he has explanations. Told, for example, that Philadelphia, more than twice the size of the District, operates on roughly half the budget, he counters: ”Philadelphia doesn’t have county and state responsibilities. It doesn’t have our Medicaid responsibilities; it doesn’t have DC General and its 23 service centers. It doesn’t have a Lorton .” But Marion Barry does have a DC General on his hands, and a Lorton. He also has a debt of at least $172 million—perhaps much more.

• • •

The camera lens is not particularly kind to Marion Barry, somehow works to make his features flatter and heavier, his whole appearance more pugnacious, conspires to make him someone not to be met at the dark end of an alley.

In person, the Mayor has presence. He has learned to look you in the eye, is softer and smoother. Up close, he is more a rangy center-fielder than a boxer, more an up-town lawyer than a union boss. Up close , you might mistake him for a banker, a diplomat, cocaine dealer, or the sort of academic that undergraduates find attractive. Up close, he is protean, slick, attractive—the hint of a caged animal wrestling inside him so he bounces into his secretary’s office as soon as he shows you out of his own, snaps his fingers time and again, and says, “Okay, what’s happening? What’s happening!”

Up close you could mistake Marion Barry for virtually anything professional save a man of the cloth. Nonetheless, Barry says that being mayor of the District of Columbia resembles few things so much as being a preacher in the pulpit,

“The preacher will preach, and people will sit there unconvinced that they ought to join,” he says. “They’ll sit there unsaved. But after a while, all of a sudden they begin to believe. At the right time, people come forth and say, ‘I believe.’ But it takes time.”

Of late, and of necessity, he has been preaching the text of economic austerity, set against the Parable of the Giving Congress, while he waits for his parishioners to say, “I believe.”

But Marion Barry, who got into office without the support of the city’s religious leaders, has brought a deck of cards into the church with him. His proposals for putting the city’s books into a greater semblance of balance are a mixture of hard calculation, confrontation politics, and bluff. And of these proposals, perhaps none is more representative of all those qualities and more instructive of the Mayor’s character than his plan for personnel reductions.

On March 3, Barry presented to the Council a financial package calling for $26.1 million in program reductions, largely through a roughly three-percent drop in the city’s work force of about 41,000, modestly estimated. Under the plan, 120 positions, including 90 uniformed officers, would be cut from a police force that last year saw crime grow in the District by eleven percent. Twenty-one school-based recreation centers in predominantly black areas of the District would be closed in a city where nearly one in every two black male teenagers is unemployed- for a net savings of one tenth of one percent of present DC expenditures. And $1.5 million would be lopped from the DC Department of Labor by curtailing the summer-jobs program that had proved a popular plank of Barry’s campaign.

The reductions would cut deeply into the most sensitive areas of the city, deeply into the city’s most sensitive services. Altogether, they formed, Barry said, an intractable demand.

”If the Council refuses my package,” Barry told a Channel 7 audience in early March, ”if it doesn’t approve it by May 1, I’m going to proceed to lay off policemen, firemen, sanitation workers, and everyone else.” Marion Barry had bitten the bullet; now it was up to the Council to bite, too, even if it has power only over taxes, not program reductions.

In the manner of confrontation politics, however, there was a second message—hardly lost on those to whom it was addressed: If Congress wanted a summer of rising tempers, if Congress wanted the District’s streets filled with idle, restless black teenagers and empty of police, it could stand pat. If it didn’t, it just might have to fold, letting more of its money go to the city. Marion Barry had sat down for a few hands of poker, his favorite game.

In the manner of such politics, too, Barry has now backed down from the full adamancy of his position: The 21 rec-centers have been trimmed to 10; the summer-jobs program may survive; the May I deadline, Budget Director Gladys Mack has announced, is a “guide.” Bluster, the moral goes, is handy in a bluff; but when you’re drawing to an inside straight, it’s best not to have all your money in the pot.

• • •

The other part of Marion Barry’s big gamble—and by far the largest—is the one that has been most ill-served by time and the nation’s economic circumstances. Barry has called for an additional federal payment of $61.8 million, money in theory owed the city as part of the full ,authorized federal appropriation for fiscal 1980. In all, the supplemental appropriation Barry has called for represents more than a third of the additional funds he is seeking to close the gap on the DC budget; and all in all , it looks like the most tenuous part of the entire package.

“We’re not going to give them that money,” says Representative Charles Wilson of Texas, former chairman of the DC appropriations subcommittee, still a member and a bit of a high-roller himself. “Their checks are going to bounce if they don’t do reductions in the city’s work force. The city can scream and shout. The Post can get harelipped. But we’re not going to do it.

“Hell, we never give the full authorization to anybody. We don ‘t give it to the Department of Defense; we don’t give it to anybody. And we’re not going to give any more money to the District while we’re cutting Social Security. ”

There is, of course, an end point to all this maneuvering—a point when the bills become due; and for all its own bluster and bluffing, Congress has always been the bottom-line giver in the District, though not always without extorting its own price.

“The entire program proposed by the Mayor,” says a congressional staffer long familiar with District affairs, “is a well-engineered package for a federal bail-out. The Mayor’s proposals almost assume a bail-out, and a bail-out may well lead to a demand for more congressional control. Looking back since home rule, the general nature of scrutiny of the budget has grown less and less severe in the spirit of self-determination. We only make broad suggestions , but this could lead to a total reversal of that situation.”

“The District has no automatic fallback to the federal government,” says Philip Dearborn of the Greater Washington Research Center, a veteran maven of DC finances. ”It has a line of credit with the Treasury, but the District has its own bank accounts. If the situation reaches the point where the District can’t meet its obligations, then the city has to go back to Congress on an emergency basis, and this is a completely different circumstance. At that point, it might go very much like New York City. I can ‘t imagine that Congress wouldn’t rub its hands a little.”

At that point, too, Marion Barry may go down in local history as the mayor who watched home rule float off down the Potomac in the general direction of Capitol Hill. Stranger things have happened in the sort of high-stakes poker the Mayor has chosen to play, which is perhaps why Barry is quick to establish his exoneration here as well.

“If home rule is threatened,” Barry says, “it’s not going to be because of me. It’s going to be because people were against it anyway. They’ll use all kinds of excuses. They ‘II say, ‘Aw, they don’t know how to run things.’ They’ll find argument after argument. You knock one down, and they’ll find another one.”

The climate seems right for this sort of battle. “In the three and a half years I’ve been on the Senate DC appropriations subcommittee,” says its chairman, Patrick Leahy, ”I’ve never heard so much ill will toward the city. ”

Barry’s contribution to that ill will may occasionally have been more than marginal—back in 1977, before he had to deal with Leahy on a one-to-one basis Barry called the senator’s native Vermont a “rinky-dink state “—but the antagonism appears to be directed more at the city’s inaction than at its mayor.

“Everybody on the House DC subcommittee likes the Mayor personally,” says Congressman Wilson. “The Mayor understands the problems and knows what to do; but he gets back up there with his political advisers and they bluff him up. The city needs experience to make hard decisions and not absolutely panic whenever four people with a placard show up at the District Building.”

• • •

For Marion Barry to fill his inside straight—for him to convince those feeling pinched by taxes that they must dig a little deeper into their pockets, to convince those feeling underserved by society that they must expect even less on their plate, and to convince Congress to come forth with cash but not controls—he must operate from a position of personal political strength. Barry sneaked into office with the approval of 34 percent of those voting, hardly a mandate. To build a greater base, he has had to try constructing a machine—to become, despite heated denials and hairsplitting distinctions between builder and boss, a Daley-type political boss.

”I’m not a political boss,” says Marion Barry. “I don’t tell people you can’t run for office. That’s what a boss does; a boss muscles in. What I say is, you can run but I’m not going to support you and I may run someone against you. ” Perhaps he protests too much; while bossism is an ugly word in some quarters—some say that Barry’s political opponent Sterling Tucker lost the election on that issue elsewhere it has a welcome ring. Bosses, at least, get potholes fixed.

“Any politician who does not try to build an organization will not be in office very long,” admits Barry. “If you don’t do that and you ever decide to run for office again, you can hang it up.” So the Mayor, never one to apologize for personal ambition, has spent considerable effort trying to consolidate his own position, within the confines of a civil-service system that protects the bureaucracy and robs him of footsoldiers. Though he is no academic student of politics, some of his machinations must bring a smile to the lips of Mayor Richard Daley in whichever extraterrestrial municipality he now resides. Daley might even have heard echoes of himself recently when Barry, under sharp questioning by news reporters as he was defending his strategy for weathering the financial crisis, snapped at one: “What proposals would you suggest?” Daley’s favorite response to critics was, “It’s easy to criticize. It’s easy to find fault. But where are your programs? How many trees have you planted?” A boss co-opts his former foes and surrounds himself with longtime loyalists. One of Sterling Tucker’s key advisers during his campaign and the head of the Democratic State Committee, Robert Washington, gets taken along to Africa and his sister gets the plum job of chief congressional lobbyist for the city. Black ministers, never in Barry’s camp, nevertheless get sweet rolls and sweet talk at breakfast. Even though civil service denies the mayor the power to hire and fire his Cabinet, Barry has reorganized, gerrymandered, and out-stared almost every inherited holdover; the city’s department heads are now almost all Barry men. And there is now a whole new layer of advisers like Georgetown fundraiser Ann Kinney, who counsels the Mayor on economic development, a platoon of ”special assistants” rewarded for their perspicacity in picking the winning candidate in 1978.

A boss uses the governmental machinery at his disposal to reward contributors. A group of ”concerned” restaurant and bar owners assembled—and dunned—by Barry campaign fundraiser Stu Long, himself owner of such city-regulated watering holes as Jenkins Hill and the Hawk and Dove, was assured that the Barry-stacked Alcoholic Beverage Control Board was in their corner; the Mayor personally suggested that they check the number of new liquor licenses issued in Georgetown in 1979, confiding: “You won’t find many.” A dance attended by a thousand gays, a community claiming a substantial role in Barry’s election, was allowed to continue, despite advance indications that the warehouse in which it was to be held posed substantial fire and safety dangers. Although specific intervention by the mayor’s office was denied, the police department, which overruled the fire department’s suggestion that the warehouse be closed, obviously acted on the belief that hands-off the gays was the most prudent course.

• • •

A boss helps other officeholders loyal to him into elected office. To replace himself as councilmember, Barry wanted John Ray, who had not coincidentally dropped out of the mayoral race and thrown his support Barry’s way. Selection, however, was to be made by the

Democratic State Committee, many of whose pro-Barry members were slated for political appointments and would thus have to resign from the Committee under the Hatch Act; Barry solved the problem by installing the members in their new city jobs but keeping them off the payroll until after the Committee met and appointed Ray. Later, Barry backed a slate of candidates for the DC School Board, in an unsuccessful effort to gain indirect control over that stubbornly independent and uncooperative body.

A boss infiltrates the lower levels of politics. Ward organizations have been taken over by Barry loyalists; one city councilmember has complained that it is not enough to be a Barry supporter, you have to be in his inner circle.

Not all of Barry’s herculean efforts at building an invincible political machine have worked. His manipulations on behalf of John Ray gave him an early aura of ruthlessness and did little more than create a gadfly councilmember. His department heads frequently war with his special assistants, such that one person who does much business with the city despairs that so little gets decided. Barry’s hand were burned by his failure to put all his School Board candidates over the top. Despite the jolly time Barry and Robert Washington had in Africa, the Democratic State Committee remains free from Barry’s thumb; a frustrated Barry even muttered an idle threat to run for the top job against Washington. And at least one observer predicts that the political maneuvering of the ABC Board may prompt an outside investigation.

Still the Mayor tries, and his appointees get generally high marks. To his credit, also, Marion Barry is aware that perhaps the truest way to build a power base in Washington, to become boss of all he surveys, is to keep the people happy with the way the government serves them. Barry’s highest marks have been earned with his improvement of the way the city works. From one-stop licensing procedures for small businesses to the promptness with which telephones are answered at the District Building, from the decentralization of automobile-tag renewals to name plates on all city employees, the delivery of services—the essence of local government—seems smoother. The Mayor is directly responsible. He quietly Jet it be known that inefficient and discourteous public employees will feel considerable heat; several high officials in the city’s troubled housing department were recently fired for incompetence.

Not all of this has made for happier employees at the District Building. “Barry and his people play a lot of games,” one high employee there complains. “They reach down into the middle layer of the bureaucracy and grab some malcontent and tell him to spill out all his problems to them. Then they come to the top level and say, ‘I hear that so-and-so …. ‘ It’s a useful device within bounds, but you’re constantly on the defensive.”

Whatever the devices used, however, at least on the surface they have created an impression of municipal efficiency in the District, and for anyone who has dealt with city government here in past years, that is change enough.

Walter Washington, you will recall, rarely fired anybody, and virtually nobody answered the phone at the District Building during Washington’s years as mayor.

”Marion is more disposed to build a political machine than Walter was,” says a high-ranking employee of the former mayor. “Marion is a pure political creature, but Walter was a product of the bureaucracy of old with no inclination toward machine-building.”

Arguably, it is pure political creatures who get things done in a mayor’s office.

• • •

Barry’s 1978 election was partly a freak of history—his opponents, this city’s two most powerful political leaders, Mayor Walter Washington and Council Chairman Sterling Tucker, canceled each other out—partly the result of a carefully crafted strategy by Marion Barry’s longtime close friend and adviser, Ivanhoe Donaldson.

Donaldson, whom one high Democratic- party official ranks among the most brilliant political strategists in the country, now serves as Barry’s official eminence grise in running the city; the unofficial eminence is said to be C&P vice-president Del Lewis. Guided by Donaldson, Barry used the techniques they had learned together in the South of the 1960s, canvassing neighborhoods, wooing the disenfranchised, paying attention to the previously ignored. The coalition of young liberal whites, gays, Latinos, feminists, preservationists, and some business interests was ungainly; but it was enough in a three-way race. It will not work again.

How large is Barry’s boat? In pulling on board enough of the 66 percent of voters for whom he was not the first choice for mayor, must Barry jettison some of his original supporters? Political debts have been duly paid off, Barry being no rank ingrate, but now the future must receive attention; and it would require the ability of a master politician to reconcile some of the inevitable conflicting interest groups vying for his affection.

Can he continue to embrace the gays so openly under the disapproving gaze of the conservative black middle class, who go faithfully to both church and the polling booth? In an era of government retrenchment, can he give jobs to Hispanics when blacks ·are being cut off the payrolls? Is the Barry reelection boat large enough both for the unions, who will not surrender their cherished high workman’s compensation, unemployment payments, and minimum wage, and for the business owners, who moan that they will move across the Maryland line or the Potomac River if those same benefits are not whittled down? And can Barry continue to preach quality education and still protect the city’s teachers from the School Board, as he did during the 1978-79 strike? Can he continue to acknowledge that teacher profligacy is a significant part of the city’s school problems without wading far more deeply into all the political sensitivities of public education?

One high-ranking member of School Superintendent Vincent Reed’s staff says simply that Barry has given up on public education in the District, deciding that the schools can never be much more than a warehouse operation. Barry says only, “I’m not doing much in education,” and bucks the blame to the Board of Education that he couldn’t stack: “Most of them have been uncooperative. They’ve been recalcitrant; they’ve spent their time of trivial things.”

• • •

Will Marion Barry go down in District of Columbia history as compromiser or polarizer? The early going has been rough.

Among the first losers in the retooling of the Barry constituency must be counted the preservation people—mostly white, mostly affluent warriors against the chewing up of downtown residential neighborhoods by ever-expanding commercial development. The battleground was the Washington Hilton Hotel on Connecticut A venue; the battle has been bloody.

In August of 1979, Barry addressed a motley assortment of protesters fighting the Hilton’s plan to expand by knocking down three handsome turn-of-the-century apartment buildings anchoring the southern end of Adams Morgan and occupied primarily by elderly residents. “I am with you on this one,” he told the cheering crowd, including several senior citizens who manned the picket line in walkers. The preservationists were pleased.

“All during the campaign he supported the need to save neighborhoods for their residents,” says Carol Gidley, the former chairman of the Citizens’ Planning Commission. “He supported us at McLean Gardens, at Friendship Heights. Barry said he was with us all the way, and then he turns around and does this.

“I think he’s more concerned right now with deal-making. He wants to get long-term investment in the town. But there’s something amoral with trading off residents for that.”

And in April of 1980, even the trade-off was stymied. The DC Zoning Commission, exercising a bit of independence, turned down the Mayor’s planning people, who had attempted to push through the Hilton plan; a delay on the buildings’ destruction was declared.

The Hilton Hotel flap has hurt Barry among the white, liberal voters in Ward 3, the far northwest of the city, which Barry carried convincingly in 1978, and in the downtown Wards 1 and 2, whose residents live in uneasy accommodations side-by-side with commercial development that threatens to metastasize.

“We had fundraisers for him in our homes because we wanted to make sure that this aggressive man was elected, ” says Gidley. ”In the last six months, a terrifying number of people who were very fond of the Mayor have been talking about getting him out of there …. He had a hell of a campaign effort in Ward 3, and he doesn’t have that anymore.

“Maybe he was embarrassed by the support he got in Ward 3.”

One well-placed municipal planner suggests Barry went with the hotel expansionists at least in part because he was annoyed with the pressure that antidevelopment forces have tried to exert on him since his election—pique being not entirely unknown as a motivator among politicians, especially those adverse to being leaned on. The same source notes, however, that Barry is desperate to expand the city’s tax base and that hotels are central to the District’s billion-dollar-a-year .tourism and convention business. City economic-development officials are also quick to point out that eighty percent of DC’s hotel employees are city residents and that hotels provide a variety of management and entry positions for chronically underemployed minorities.

Nobody, at least, is saying that the Mayor’s decision was made in a vacuum. If the preservationists feel as though they’ve been thrown overboard—the destruction of the historic Rhodes Tavern in favor of yet another Oliver T. Carr office building being another sore spot—there is other cause for uneasiness among those Ward 3 voters who thought they had placed a friend at city hall and who now perceive acts of polarization rather than conciliation, including:

• The sparseness of white faces among Barry’s closest advisers.

• Barry’s approval of the concept of minority participation in commercial development projects, which meant giving equity shares worth millions to politically well-connected black businesspeople in return for nothing more than lending the project the recipients’ minority status—a concept termed extortion by one major developer.

• Barry’s knee-jerk application of the time-honored tactic of choking off debate on his actions by calling his critics ”racist”—witness the Post’s Richard Cohen, who wrote several scathing articles about Marion Barry’s personal problems and his much-publicized, fed federally financed African trip, and who for his efforts was publicly castigated on television and privately cursed out on the telephone.

“Barry is going to ignore the white voters of Wards 2 and 3 next time around,” a former Walter Washington official predicts. ”He’ll pay lip service to the needs of white liberals for a while longer. But it’s a difficult coalition to hold together, and they’re not going to be happy with the development and with the inevitable higher tax loads.”

• • •

Across town in the poorest sections of Washington—particularly Ward 8 in Anacostia—longtime fears of being ignored by the powers that be were rekindled by Barry’s ill-advised attempt to cut garbage collection there to once a week. The proposal seemed sound: By providing Ward 8 residents with huge garbage containers on wheels, which needed to be emptied only once a week, the city could save $700,000 and 38 jobs. The outcry was louder—ironically enough—than the complaints surrounding a twin proposal to lop off $10 million and 500 jobs from the public-school system.

One longtime District Building watcher points out that the once-a-week garbage collection idea was nothing new; Walter Washington had it on his desk—and then on a back shelf—for years. Washington knew that some things were inviolate and that garbage collection in the poor part of town was one of them. Says this observer: ”If Barry had only proposed the plan for selected routes throughout the city—in every ward—he would have avoided organized opposition and charges of discrimination. Hell, he could have done it safer in the rich neighborhoods of Ward 3. Sixty percent of their garbage is newspapers, and they don’t stink.”

Wilhelmina Rolark, Ward 8 councilmember and watchdog for its poor, warns: “There will be outward hostility if Barry starts all these cuts. We have so few services out here in Ward 8 as it is. We’ve got 22 percent of our people on public assistance, and I’m concerned about the Department of Human Resources cuts. They say they’re going to cut down on the level of street and alley cleaning, but we’ve got garbage piled up everywhere.”

The garbage-collection fiasco ended with an admission from Barry that, “I think we made a mistake,” and with Barry carrying home the sample garbage can on wheels . It can be convincingly argued that this episode was not a mistake of the heart but the result of the understandable lack of political adeptness by a new administration. But the suspicion persists that Barry’s political strategists have not lost their Machiavellian flair.

”I don’t think Barry can move away from the support he got in Ward 3,” says Council member John Wilson, “but he’s got to expand his base to Ward 8. The voter turnout is fickle in that ward, though; and the eighteen- to thirty-year-olds who are most likely to vote for him are the most fickle voters of all.”

• • •

With his Ward 3 coalition of 1978 inevitably volatile and with the city’s poorest voters likely not to show up on election day, there remains for Marion Barry the political center of the District—the black middle class.

“Marion Barry’s natural following is not the black middle class,” says one high-ranking local politician, “but that’s the group he has to go for.” Arithmetic bears that out: In an almost-even three-candidate race, fringe groups ca11 form a winning plurality, but for the score in a two-candidate race to add up to 51 percent the mainstream must be forded.

Barry’s political move to the middle—the non-white, non-poor—seems as logical and as calculated as his personal move from Capitol Hill, with its mix of white liberals, gays, and poor blacks, to the manicured hillside of Ward 7’s Hillcrest Heights, bastion of the black professional and the solidly middle class. And if the movement toward the middle-class black voters of the city is either the design or the drift of the Barry administration, then more battles will be lost than won by the people west of Rock Creek Park and east of the Anacostia River.

“Marion has always been a person who identified his constituency and went for it,” says Councilmember David Clarke, a frequent Barry ally and an acquaintance since his earliest days in Washington. Few people doubt he’II continue to do that now.

Where does Marion Barry go from here? To hit for the cycle in local political office-holding, he need only become congressional delegate, but while the prospect of dislodging his frequent rival Walter Fauntroy would be tantalizing, the job itself is not to his taste. Fauntroy is judged more vulnerable than at any other time in his political career—the result of flirtations with the PLO and Edward Kennedy—but the office remains ceremonial and impotent. In the words of comedian Mark Russell, Fauntroy shows up at Congress every day and asks, “Can I watch? Can I watch?” And no one can picture Marion Barry merely watching.

In the uncertain event that DC attains statehood within his political prime years, one of the two Senate seats might well be Barry’s for the asking. Until then, however, the Mayor has nowhere to go but where he already is, an unsettling prospect for a man who admits: “I have not been satisfied with staying in one place too long.”

“If you look at any rise of a political figure in America,” Barry says, “you find that they are successful if they take advantage of opportunities when they arise.”

Also at the back of the Mayor’s ambition, he admits, is the day three years ago when he took a bullet in the chest on the fifth floor of the District Building, during the Hanafi-Muslim takeover:

‘Tomorrow is not promised to you,” Barry says now. ”I knew that, but you never really get it until it hits home. It’s made me more impatient about getting things done.”

If Marion Barry wants to give his ambition a rest for a while, he can be comforted by the knowledge that at the moment there seems to be no one to threaten him. At best, however, that is a temporary situation, ambition in this city not being unique to the Mayor.

Overcoming her double minority status might be intriguing challenge enough for Betty Ann Kane, the white councilmember-at-large. HEW Secretary Patricia Roberts Harris is mentioned with surprising frequency, although the city would get her strictly on the rebound: If passed over for the US Supreme Court, if tired of wrestling with a huge morass of national bureaucracy, or if thrown out of work come November, she might want the job. Democratic State Chairman Robert Washington, whose Number 2 license plate is only the iceberg’s tip of his power and influence, would be an attractive challenger—although his name is unfamiliar to an electorate in which name recognition is all; and as a partner in a prestigious law firm, he might not find the downgrading in salary offset by the upgrading in license-plate number.

By his aggressiveness, Barry has already effectively neutralized one automatic rival—Arrington Dixon, chairman of the DC City Council. Barry’s clear identification, for good or ill, as the head of the executive branch has robbed the office of City Council chairman of the star-making potential it had when Walter Washington was running the mayor’s office and Sterling Tucker—to the outward eye, at least—was running the city.

For the present the only person able to make Marion Barry stumble is Marion Barry himself, and now that the glamour of the street-activist-turned-mayor has worn a bit thin, rumblings of doubt about the man are beginning to be heard. Political associates with eyes on the great middle-class constituency shudder at the sight of their discoing, roaming leader, whose reputation as a man with a weakness for the ladies has remained undimmed by marriage and mayoralty.

Marion Barry has also been hurt, especially among white voters, by the accumulation of small charges against him—the growing catalog of petty malfeasances and corner-cutting that includes the loan on his $125,000 house, which he was forced at journalistic gunpoint to admit was several interest points below prevailing rates; an inexplicable misleading of the press on the level of his wife Effi ‘s salary—for a number of months it was reported at $60,000, until her employer, Pacific Consultants, which gets financial assistance from the Small Business Administration, made her confess it was nearer $30,000; and the politically clumsy nick-of-time salary hikes for close associates on his executive staff mere days before his budget ax was wielded. Indeed, it is hard to spend much time discussing Marion Barry in Cleveland Park, in Burleith, in Georgetown, or in Wesley Heights without someone ‘s suggesting that he is the sort of opportunist that local politics has long produced.

“Barry spent a lot of time in Ward 3, telling whites what they wanted to hear,” says a longtime savant of District politics. “And he’s lost that popularity. The business of the home loan is offensive in the white community—not that they don’t do it themselves, but they are more hypocritical about it. In the black community, the home loan is more understandable; it’s seen as playing the Man’s game.”

All of the above may be dismissed as carping by those whose knives would be out for anybody in high office, but one potential time-bomb ticks away: Pride Inc.

• • •

The few insiders who will talk at all about the matter, even off the record, suggest that Marion Barry could be brought down far more quickly—and far more in the classic manner of city bosses—by the scandal that has embroiled the management of the Clifton Terrace apartment complex by a subsidiary of Pride Inc., and particularly the part of Barry’s second wife, Mary Treadwell, in that scandal. Barry and Treadwell were married for part of the time that Treadwell was allegedly siphoning money out of public grants to the complex.

The Mayor has avowed his innocence, and no evidence has surfaced to suggest otherwise. However, rumors of an ever-widening federal investigation of the overall activities of Pride Inc., inextricably linked to the political career of Marion Barry, are flying as fast and thick as subpoenas in Barry’s direction; and Treadwell has allegedly spread the word that she, who is said to bear a monstrous grudge and a vengeful heart, is not going down alone.

“If what Mary Treadwell is saying is true,” says one insider who would discuss the issue, “Marion cannot survive. The home-loan business is okay; but when it is blacks ripping off other blacks, that is disastrous. And the Pride scandal is black versus poor black.”

If, however, the Clifton Terrace-Pride case comes to involve Barry himself, it is likely to provide an interesting test case of the influence of the press. And the press would not necessarily win in a showdown with Marion Barry.

‘The joke around the District Building,” says someone who holds a position of substance there, “is that if you get knocked in the Post you ‘re one up. Inside the city limits, it’s all upside down.

“You’re dealing with an electorate that for the most part isn’t going to concern itself with legal niceties. And Barry can turn this to his advantage . He can say, ‘The hookies have done this kind of thing all along. Now they’re out to get me.’ As long as it doesn’t get down to carrying him off in handcuffs, he’s going to win points on it. Short of that, the guy is fairly invulnerable.”

What is certain is that the press will come down hard on Barry if it gets an opening. His early trip to Africa may have been covered much in the manner of Pope John Paul II’s trip to America, but the honeymoon between Marion Barry and the Fourth Estate is over.

Finally, too, it is hard to tell just how firm a grip Washington’s dailies have on the local political process. At least one politician here, Betty Ann Kane, thinks one of them does have a bead:

“The Star,” Kane says, “has a sense of the political life here. The Star digs so much more; their people work harder and get so much more stuff. The Post is still constantly referring to the ‘rag-tag band of workers’ who put Barry in office. That’s completely out of touch with reality. Those were some of the most savvy people in the city.”

The February issue of “New Times,” the house organ for the city’s employees, carries a photo quiz that shows a forlorn bit of local statuary, surrounded by the artifacts of new construction. Can you identify the man represented by this statue, the quiz asks, and for five extra points can you tell where the statue is now located?

The answer to the first part of the question is Alexander Shepherd, the last governor of the District of Columbia, known to friend and foe alike as ”Boss.” It was Shepherd who, in the national economic slump of the early 1870s, set about repaving the roads of the city after Union troops stationed here during the Civil War were through destroying them. It was also Boss Shepherd who appealed to Congress to bail the city out of the obligations to contractors and lenders that the roadwork brought on. And it was Shepherd who, in 1874, saw Congress grant his bail-out request- and for penance strip the city of its political autonomy. DC is just recovering from that.

For his troubles, Alexander Shepherd was honored by a statue and placed on a pedestal on Pennsylvania Avenue, dead across from the District Building; but that is not where he is now. The answer to the “New Times” extra-credit question is that the statue now stands in an obscure storage area on Fourth Street, Northwest. The extra-credit section is more telling than the main one.

The overt reason for Boss Shepherd’s removal from his station on Pennsylvania A venue was that his old site was being torn up as part of the A venue’s redevelopment plan. But symbolically the move was appropriate as well. The Barry administration didn’t need the Boss around as a constant reminder of the possible consequences of a failure of nerve and resolve; nor with Alexander Shepherd banished to storage could there be any doubt around the District Building or in the city as a whole about just who, for better or worse, is boss these days .

For the moment, Marion Barry is that boss.

This article appears in the May 1980 issue of Washingtonian.