APX Labs is one of the sexier start-ups in the Dulles Tech Corridor. The company develops software for wearable technology such as Google Glass and is one that many are happy they got into early—a start-up where you might hear an employee name-drop his place in the pecking order, as in “I’m employee number 11,” a prime position if APX should ever go public. But as the firm has matured since opening in 2010, so have its workers. The Herndon staff, mostly male twenty- and thirtysomething developers who come to work in T-shirts, jeans, and bright-colored sneakers, is experiencing a baby boom. Over the past two years, about a quarter of the 43 employees, including the 34-year-old CEO, have become dads. And that means that these days, stock options aren’t the top perk employees negotiate. For many, flexible schedules are just as important.

APX meetings are typically held between 10 am and 2 pm as a concession to staffers who need to leave early or show up late, and every dad is encouraged to take a paid two-week paternity leave. If someone has to leave the office for a soccer game or doctor’s appointment, colleagues pitch in.

“We think of ourselves as a band of brothers,” says Ed English, father of a 12-year-old and a 14-year-old and, at 46, the older-and-wiser of the staff. “We say: ‘Leave work, take time off, unplug with your family—we got it. At some point, it will be your turn to pick up the slack.’ ”

The APX culture has mostly been this way from the beginning, but its policies have evolved over the years to accommodate working parents like Oren Fromberg. Every day the 33-year-old has to leave by 4 to get his kids from daycare by 5. His wife, a veterinarian, is still at work while he makes dinner (Easy Mac and fresh-cut fruit), gets the children bathed, and, fingers crossed, tucks them into bed before 9.

One night earlier this year, Fromberg was telling his three-year-old son a story about firemen when he fell asleep mid-sentence—he woke up to his boy doing acrobatics on the bed. “By the time my wife gets home,” he says, “we’re catching up, doing chores, before we collapse on the couch, just wiped.”

Fromberg hates to kvetch. He’s thankful to have a great job and an amazing family. But sometimes he can’t help it. Every morning he and Eric Levine, a new dad who sits in the opposite cubicle, compare notes about the night before. “How did bedtime go?” they ask each other.

“I can often tell,” says Fromberg, “just by looking at him.”

Levine’s wife stays home with their 21-month-old son, so he’s responsible for the evening shift. He likes the responsibility—he actually struggles being away from his boy all day. He just he wishes he could get home with more energy.

“It feels like I have two jobs: my day job and my night job,” he says. “When I’m home, I want to spend time with my son and I want to give my wife a break. I want to do all I can to pull my weight.”

• • •

Managing the constant push-and-pull of career and family is a perennial source of anxiety for women, as Sheryl Sandberg (Lean In), Anne-Marie Slaughter (“Why Women Still Can’t Have It All” in the Atlantic), and most recently the Washington Post’s Brigid Schulte (Overwhelmed) have reminded us over the past couple of years. But now a new generation of dads is feeling overworked at the office, overstretched at home, and overtaxed overall, too.

Nearly 60 percent of married couples with kids live in two-career households, up from 25 percent in 1960, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics. And even though fathers spend more time at the office than mothers (42 hours a week versus 31) and mothers spend more time than fathers on child care and household chores (28 hours a week versus 16), “when their paid work is combined with the work they do at home, fathers and mothers are carrying an almost equal workload,” says a groundbreaking 2013 Pew Research Center study of 2,511 adults called “Modern Parenthood.” When asked if they struggle juggling work and family, 56 percent of the women and 50 percent of the men reported yes.

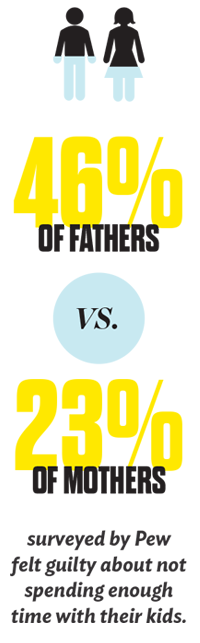

A good amount of the stress seems to come from feeling rushed, with 40 percent of the working moms and 34 percent of the working dads with children under 18 saying they always feel they’re doing too much too fast. But it’s fathers who overwhelmingly think they’re giving their kids short shrift: 46 percent reported feeling guilty about not spending enough time with their children, compared with 23 percent of mothers.

The results were an eye-opener for the study’s coauthor, Kim Parker. The thing that surprised her most: Half of the dads polled would choose to stay at home if money were no object. As Parker puts it, “Men are not supposed to say that.”

• • •

Henry Avery is used to his father doing preschool drop-off and pickup, and he knows that when Daddy is in his “office”—the desk near the dining room—he should focus on building a tower with his blocks.

Justin Avery is a sales director at Global Knowledge, an IT and business training company headquartered in North Carolina, and works at home in Arlington to be with Henry in the afternoons. Three years ago, the 42-year-old was shopping for a new job, and the ability to telework was a top priority. Still, he was coy about that desire early in his job search. “I hate to ask about work/life balance first—if you lead with that question, companies may be turned off,” Avery says. “It’s like asking, ‘How much does the job pay?’ ”

Nearly every potential employer touted its family-friendly culture, but when he pressed human-resources directors and managers for concrete examples, the interviewers fell short. Avery ended up turning down several consulting positions that would have paid up to a third more than what he makes at Global Knowledge. The firm won him over after several managers and HR folks described leaving the office early to see a child’s school play or working at home a few afternoons a week. Flexibility trumped title and salary.

That kind of tradeoff is something many more men are choosing, says Gayle Kaufman, author of the 2013 book Superdads: How Fathers Balance Work and Family in the 21st Century. The Davidson College professor interviewed 70 men and found a number of what she calls “old dads,” who cling to the traditional provider role, as well as “superdads,” who leave a high-paying position and upend their career path. But the majority were “new dads”: men who want their job titles to be both chief breadwinner and dad of the year.

These are the guys who are struggling the most. “They really want to spend more time with their kids, but they feel constrained,” Kaufman says. “There’s only so much they can do within the confines of work.”

Geoff Hardy, a graphic designer at STG, a government contractor in Reston, is an example. He and his wife, Sarah, recently shuffled their work/life routines so they could take their son and daughter out of their daily after-care program, a shift that came about because Hardy hated that his kids weren’t riding their bikes or playing in the back yard after school. “I love that my son gets home and has all of this freedom now,” Hardy says. “Before, he too was essentially working all of the time.”

The trouble for Hardy—who convinced STG to let him telecommute a couple of days a week—is that “working at home” comes with all kinds of interruptions. While his nine-year-old son can play at a friend’s while he’s at the computer on the job, his four-year-old daughter needs more attention. Hardy often has to go back online after the kids are in bed to finish his work.

“Come Saturday, we’re playing catch-up on a million things you have to do during the week—we don’t even have time to mop the floor,” he says. “I feel like I live in a house of chaos and clutter.” His kids know to dig through baskets of clean laundry for their clothes.

Dads with teenagers may feel the tug between office and home even more acutely. Last fall, Damon Watts, a 44-year-old managing director at Accenture, decided he should drive his 13-year-old son to Bethesda’s Landon School every morning so he could have that 45 minutes in the car just to talk. Maybe about the game, maybe about girls, maybe about nothing much. “At 13, you’re going from a child to some form of adulthood,” Watts says. “You’re exposed to drugs, sex, all things where it’s important to have a parent looking over your shoulder.”

Whereas moms are more likely to ask their bosses for special arrangements, research shows that dads today tend to go about things unofficially—quietly slipping out early, for example, or announcing that they’re working from home rather than explaining why or asking permission.

Watts didn’t have those options. He was generally out of town Monday through Thursday, and he was anxious about asking his boss for special treatment to work more locally—he worried it might make him seem less committed. But he was buoyed by some of the mothers and at least one father at Accenture who’d made similar requests, successfully. So he went for it. And to his relief, his boss understood.

Women certainly know the sting of being passed over for promotions or having their salaries docked after having kids. The downsides for dads tend to be less tangible, but some research shows there might be a social cost for men who prioritize parenthood. A recent University of Toronto study found that fathers who talk more openly about caring for their family are sometimes treated worse at work—harassed, made fun of—than men who hew to traditional gender roles.

In other cases, fatherhood can be a status booster. Researchers at the University of Massachusetts published a study in 2010 showing that married dads—white, straight, and well-educated managers in particular—make more money than child-free men. Academics are now asking why that might be the case: Is it because these fathers sought out bigger roles in anticipation of having a child to support, or perhaps because they tend to pursue more stable jobs?

Brad Harrington, who studies fatherhood in his position as executive director of the Boston College Center for Work & Family, isn’t so sure the UMass results reflect a positive development. As a thirtysomething father in one of his studies told him not long ago, “You know why dads get all the kudos in the workplace, right? It’s because nobody takes fatherhood seriously.”

• • •

Judith Sandalow works to make sure the opposite is true at her office. The executive director of the Children’s Law Center in DC—and a mother of two boys—says women tend to talk to other women at work about their families but dads don’t take to that kind of chat as naturally. So in meetings, Sandalow goes out of her way to ask about their kids. “We want our male employees to know that we think of them as fathers,” she says.

Staffers have unlimited sick days, and regardless of their gender they’re supposed to stay home if their child is sick. Sandalow also says dads would likely be chastised if they didn’t take their allotted six weeks of paid paternity leave.

As a boss, she’s a rare find. Only about 15 percent of companies in the US offer paid paternity leave, according to the Society for Human Resource Management. And one study Harrington conducted shows that fathers rarely stay home more than two weeks. “There is an internal reference or corporate vibe that two weeks is the sweet spot for dads,” he says. “Any more was seen as inappropriate, even if the company encouraged them to do so.”

Last year, after the birth of his third child, CNN reporter Josh Levs filed a discrimination complaint with the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission against CNN’s parent company, Time Warner, for treating dads unfairly by granting ten weeks of paid leave to biological mothers and any parent who adopts but offering biological fathers only two weeks off.

“I have only two choices: stay out for ten weeks without pay or return to work and hire someone to come to our home each day,” Levs wrote on his Tumblr page. “Neither is financially tenable, and the fact that only biological dads face this choice at this point in a newborn’s life is ludicrous.” (Levs’s attorney says the EEOC is still evaluating his complaint.) The outcry in Levs’s favor was so intense that he’s now writing a book about dads that’s being marketed as the antidote to Sheryl Sandberg’s Lean In. The working title: Stretch Out.

Reston couple Steve and Marieke Ertel are trying to alternate which of them hangs back and which one marches ahead, renegotiating their child-rearing responsibilities a few times over the ten years since the eldest of their three was born. Steve, 36, is head of public relations for the World Wildlife Fund and gets 300 to 400 e-mails a day. Marieke, 37, has become a music teacher again, in Fairfax County, after nine years as a stay-at-home mom. That change has forced Steve to pull back a little at work—going in later, delegating more, and traveling only when he has to.

On school days, he gets the kids ready and shuttles them to before-care each morning at 7:30, blasting songs from the Frozen soundtrack or, if he’s lucky, one of his picks, like Aloe Blacc’s “The Man” (I’m the man, I’m the man, I’m the man), before driving to work in downtown DC by 9:30. Marieke picks the kids up from after-care, makes dinner, and walks the dogs.

The couple is extremely conscious about showing their children a more equitable style of parenting than the one they grew up with. Marieke doesn’t want their daughters to think mothers are supposed to bear the burden of caring for kids, and Steve doesn’t want his son thinking men care only about their job.

They say they don’t keep a list of who’s doing what—it’s more of a divide-and-conquer approach. “I think because we both take on a portion of the responsibility, it’s more peaceful,” Steve says.

The Ertels’ setup is the one most likely to multiply among the next generation—which is already skeptical about having it all, according to new research by a Wharton professor of management named Stewart Friedman. He conducted a cross-generational study of the school’s graduates in 1992, then again in 2012, and found that the number of 2012 graduates who planned to have children dropped by nearly half compared with those who graduated 20 years before.

The reason seems to be directly related to work: The millennial graduates of 2012 are expected to be on the job 14 hours more per week than the Gen-X cohort who entered the workforce in 1992.

As a result, Friedman believes, millennials are thinking about work/life balance in a new way. They don’t assume Mom will stay home while Dad becomes the primary breadwinner. They don’t even assume both parents will work. Instead, he writes, dual-career millennial couples are more likely to “experiment with new models for how both partners can have more of what each wants in life.” Put another way: They’re likelier to decide which parent will lean out and when.

• • •

In some ways, the anxiety among young working dads feels like cultural progress. Fathers are doing more at home, which is a result of women doing more at the office. But overall, even though the time dads spend on child care has jumped in the past 40 years, their investment isn’t huge. In 1965, fathers logged 2½ hours a week with their kids; today they put in seven.

To some, that means the real progress is still a long way off and won’t come until men think in terms of parenthood rather than fatherhood. Just as mothers hold themselves up to the seemingly perfect mom next door (or on Pinterest), dads tend to compare themselves to other men, according to Kaufman, who wrote Superdads. She says men don’t look at their wives and think, “I’m not doing as much as my wife.” They eye the dad at the next desk and think, “Well, at least I’m doing more than that guy.”

Joe Moore, a 44-year-old attorney in Bethesda, has been there. Before he and his wife divorced, he defined being the best father as making the most money he could—fast. Now he and his ex share custody of their three kids. “I’ve had to memorize things like my daughter’s shoe size, the name and number of my kids’ doctors, the names of their friends, and the names of their friends’ parents,” he says.

Moore often wakes up at 3:30 am to work before the kids rise or else he can’t get everything done. Every Thursday, he volunteers on their school cafeteria line, where the mostly female staff sometimes treats him like a superstar dad, which he finds silly. “Everyone bends over backwards to praise dads,” he says. “It’s like you’re the best dad in the world just for showing up.”

Justin Avery has heard the comments, too. Every Saturday, he brings Henry to Starbucks for doughnuts, and people—men and women both—stop him to say, “It’s great that you’re babysitting your son” or “How nice of you to give Mommy a break.”

What does he have to do not to be seen as second-best? “When someone calls a dad ‘hands on,’ what does that even mean?” he asks. “Because to me, that’s the job description.”

Brooke Lea Foster, a former Washingtonian senior writer, can be reached at brookeleafoster@gmail.com. This article appears in the September 2014 issue of Washingtonian.