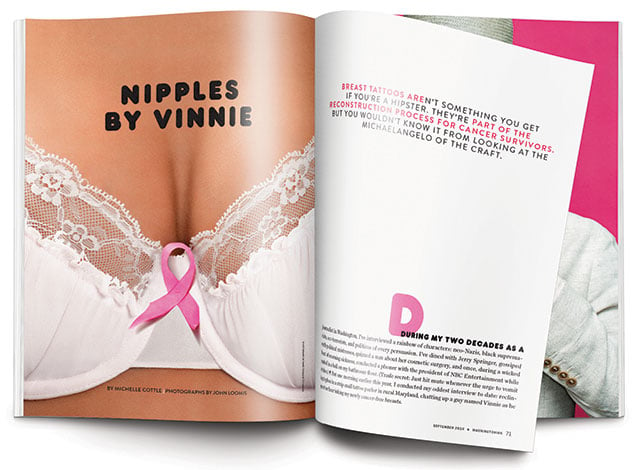

During my two decades as a journalist in Washington, I’ve interviewed a rainbow of characters: neo-Nazis, black supremacists, eco-terrorists, and politicos of every persuasion. I’ve dined with Jerry Springer, gossiped with political mistresses, quizzed a nun about her cosmetic surgery, and once, during a wicked bout of morning sickness, conducted a phoner with the president of NBC Entertainment while curled in a ball on my bathroom floor. (Trade secret: Just hit mute whenever the urge to vomit strikes.)

But one morning earlier this year, I conducted my oddest interview to date: reclining topless in a strip-mall tattoo parlor in rural Maryland, chatting up a guy named Vinnie as he spent an hour inking my newly cancer-free breasts.

My trip to Little Vinnies Tattoos began last year with the punch-in-the-face news that at age 42 I had early-stage breast cancer. For a variety of reasons, I adopted a zero-tolerance policy toward “the girls.” Thus began a bilateral-mastectomy-and-reconstruction odyssey requiring two surgeons, two trips to the operating room, three weeks of postsurgical drains, two months of tissue expanders (essentially medical-grade water balloons), multiple oncology consults, mounds of gauze pads, a liberal supply of Percocet, and more Costco-size bags of Ghirardelli chocolate than I’m willing to admit. And at the end of all that: Vinnie.

I’d been hearing about Vincent Myers almost from the moment of my diagnosis. Both my breast surgeon (the woman who stripped out the offending cells) and my plastic surgeon (who restored the landscape to more or less its original topography) love him. Adore him. Could not recommend him highly enough to do my nipples.

Though there is such a thing as a nipple-sparing mastectomy (Angelina Jolie had one), most women have both breast and nipple removed and, post-reconstruction, are left with a dome of flesh bearing a long smile of a scar where the nipple and areola once were. Some have a faux nip tattooed directly onto the dome. Others first get a surgeon to handcraft a nipplesque protrusion with a bit of snipping, folding, and stitching of the surrounding tissue, then get inked.

Either way, you need a talent wielding the tattoo needle if you don’t want to come out looking as though a colorblind toddler has been scribbling on your chest. These days, more and more surgeons are outsourcing the task to body-art experts.

Which brings us to my first meeting with my plastic surgeon, Dr. H. While my shell-shocked husband and I test-squeezed implants and perused her online “catalog” of befores and afters, she ticked through what to expect from my looming mastectomy and, beyond that, the myriad reconstruction decisions that lay before me: implants versus flap surgery, saline versus silicone, round versus teardrop, small versus medium versus porn star. . . . But whatever options I went with, Dr. H raved, I absolutely, positively had to “go see Vinnie” for the finishing touches.

• • •

Once dubbed “the Michelangelo of nipple tattoos,” 52-year-old Vinnie Myers, a former Army medic, has become a legend in breast-cancer circles. Women jet in from around the world to get one of his “areola portraits,” trompe l’oeil renderings so lifelike they’ve fooled surgeons. Myers has been honing his craft since 2001, and over the past four years it’s become the only kind of tat he does. No butterflies. No bleeding hearts. Just nipples.

It’s a draining job—playing impromptu shrink one minute, wisecracking virtuoso the next—but rather than get worn down, Myers has gotten fired up. He works six days a week now and does seven women a day (that’s as many as 4,000 nips a year), up from three a day just two years ago. And still he struggles to keep up with demand. As of August, his waiting list ran to six months.

The stats—297,000 US women were diagnosed with breast cancer last year—suggest business will only grow. “Unfortunately, there’s not going to be an end to this anytime soon,” he sighs, raising his porkpie hat to rub the sides of his shaved head.

Make no mistake: The work is lucrative—Myers charges $600 for one breast, $800 for two—and solidly recession-proof. But business at Little Vinnies Tattoos, it seems, is booming a bit too much. Vinnie, wife Robin, and manager Richie France all worry about how their shoestring operation will cope—especially when the practice has already taken over their lives. “I eat, sleep, and breathe this,” says France, “as does Vinnie.”

Indeed, what began as a savvy business niche seems to have become an all-consuming obsession. Myers now spends hours talking to doctors, reading up on treatment trends, and taking aim at what he sees as bad practices—and practitioners—in the broader field of breast reconstruction, becoming not only a psychological savior to legions of survivors by helping them reclaim a sense of wholeness but, more improbably, an impassioned medical crusader, too.

• • •

Perhaps no one is more surprised by Myers’s induction into the pink-ribbon sisterhood than Myers himself. As he tells it, tattooing was something he fell into 30 years ago while in the Army, when he wound up stationed in South Korea with a heavily inked guy from Long Island and the two realized they could make some extra cash.

By 1995, he had moved back home to Maryland’s Carroll County, married a local girl he’d known most of his life, and opened his own shop. “This was right about the time in the tattoo world that there was a changing of the guard,” he says. “The old-school guys from the ’50s and ’60s were getting old and getting out of it. Younger guys were coming in—guys who had art training.”

A decade later, a friend of a friend connected Myers with a Baltimore doctor who’d been doing nipple tattoos on his patients but wasn’t thrilled with the results. (This is hardly unusual, says Myers: “I don’t think I’ve ever seen a tat that came out of a doctor’s or nurse’s office that looked right. Ever.”) The MD wanted to see what would happen under the steady hand of a professional.

Myers discovered that he had an eye for it (especially when working with a blank canvas, as opposed to fixing a doc’s mistakes), and word of his talent spread swiftly throughout the chatty, tight-knit breast cancer community, until eventually his name reached the ears of nurse Lillie Shockney, who runs the Johns Hopkins Breast Center and its survivors’ program.

It was 2009, and she was doing a post-op appointment with a patient who’d had a traditional mastectomy with nipple removal. Or so she thought. Then she laid eyes on the patient’s reconstructed chest—and saw a pair of nipples. Shockney asked why the woman had changed her mind and opted to keep them: “She said, ‘I didn’t change my mind.’

“And I said, ‘I’m looking at them!’

“At which point the patient pointed at her chest and said, ‘Vinnie.’ ”

Shockney’s puzzled response: “What’s a Vinnie?”

The nurse’s fascination was more than professional. She’s a breast-cancer survivor who underwent her first mastectomy in 1992, another in 1994, and then a round of reconstruction in 2003. Along the way, she received a couple of what she calls “organic tattoos”—dermabrasion colorings performed at surgeons’ offices, typically by nurse practitioners. The pigment is applied using vibrating probes rather than needles, often requires multiple sessions, and fades over time. “The color goes in one, maybe two millimeters at most and is one solid color,” she explains with obvious distaste. Myers’s work was like nothing she had ever seen. She wanted her own set.

Shockney made her way to his studio in Finksburg, walked in, and thought about walking right back out when she saw a hatchet adorning one of the walls. The inking itself felt like “being chewed on with a mower or something,” she remembers. But when it was all over and Myers turned her chair around to inspect his work, she burst into tears. “I was so thrilled with what I saw. And my husband exclaimed, ‘Well! I haven’t seen them for almost 19 years!’ ”

Then and there, Shockney told Myers, “If you want to do this all the time, I have the power to make that happen. If I go public, you will not have time to do anything else.”

A year later, Myers’s friends were teasing him that he had the best job in the world, looking at women’s racks all day. But he insists he never saw it that way—in fact, it was the opposite at first. Monotonous. Artistically stifling.

Moreover, working with cancer patients called for a different work ethic than that of “a regulation tattoo guy.” The “prima donna attitude” had to go—showing up late or not at all, dressing however he wanted. With women booking months in advance, making costly travel plans, and psyching themselves up for the final stop in their recovery journeys, the job became much more structured. “I had to grow up,” Myers says. “I didn’t necessarily like that.”

At one point in 2010, Myers was ready to quit. As he puts it, “I made up my mind on a Monday. On Tuesday, my sister called me and said she had been diagnosed with breast cancer.”

He dug in.

• • •

By the time I show up at Little Vinnies four years later, the studio reflects the odd hybrid role into which Myers has settled. Center stage in the main room, a scented candle (pumpkin caramel swirl) flickers atop a large clawfoot pool table. A display case contains pink-ribbon T-shirts bearing Myers’s motto, “Tattoo the Ta Ta’s.” Nearby, an exotic lizard basks beneath a heat lamp inside a terrarium.

The walls hold a pair of giant maps with pins in Riyadh, Osaka, Rio, Paris, Kuwait, Mexico City, Hamburg, Barcaldine (Australia), Durban (South Africa), Toronto, and cities in all 50 states from which women have traveled for their custom Vinnies. Also on display: animal skulls and antique scythes.

Although Myers himself inks only nipples, four other artists do traditional tats behind a row of heavy black curtains. So while Myers’s “ladies” anxiously await their turn, they’re treated to the buzz of needles and chitchat of the other Little Vinnies patrons being gussied up with fairies or Celtic symbols.

“We thought about making the setting a little more clinical,” Myers tells me. “I talked to some of the ladies about that. They were like, ‘Oh, my God—don’t do that!’ ” After all they’ve been through, he says, “the last thing they want to do is be in another doctor’s office.”

At the same time, Myers understands how skittish his clients can be: “The majority of women that come in here would never come into a tattoo shop otherwise.” To soften the experience, he outfitted a special room with girlie pink artwork, comfy chairs, and an ambience that says pedicure salon more than tattoo parlor.

This is the room into which I’m escorted on the day of my appointment by Vinnie’s wife, a shy, blue-eyed brunette who started working in the shop this year after more than two decades at home raising their four kids. Vinnie comes loping in a few minutes later. Tall, fair, and slim, he’s partial to retro hipster getups: patterned pants, button-up vests, and wingtip shoes, all topped off with a rotating collection of porkpies he’s forever lifting and tilting, especially when he gets excited. He has no visible tats, though he assures me there’s plenty of ink beneath his clothes. (The koi and Chinese foo dog spreading across his chest, he says, took 18 hours to complete.)

I’m hardly the first to ask about his own body art. Myers recounts how once, after consulting with members of the patient-advocacy group Breastcancer.org, he went out to dinner with the gals, one of whom demanded to see his tattoos: “I’m like, ‘Right here in front of everybody, you want me to take my shirt off?’ She’s like, ‘You’re damn right! We had to do it—now it’s your turn.’ It was a good lesson for me, because I realized it isn’t easy to take your shirt off in front of a bunch of people, and these ladies do it time and time and time again.” (Yes. Yes, we do.)

Myers snaps on black gloves and asks about my reconstruction. He studies my faux nips (skillfully rebuilt, though jarringly pale) with a critical eye, makes some crack about how my surgeon has already made all the placement decisions for us, and proceeds to draw two small bull’s-eyes on my chest with pink Sharpies. Then he gets down to mixing my ink.

As I learn, achieving an authentic look is all about color. Having some dilettante slap on a circle of pink or peach or brown is fine if you want your new nips to look like something out of a Roy Lichtenstein print. (Shockney groused to me about the cartoonish, “salmon”-hued predecessors to her Vinnies: “I’m like, great—now there’s a fish on my chest.”)

Myers is methodical. He examines the whole tableau: skin tone and shading, scars, breast symmetry (or lack thereof), and, for women with rebuilt nipples, variations in size, shape, and positioning. On those without them, he has to create the illusion of all the gentle bumps, dips, and shadows found in nature—making his 2-D portraits look as if they have what’s known in the reconstruction world as “projection.”

For me, Myers starts filling a row of tiny plastic paint pots with teal, dark red, a peachy color, a smidgen of green (to cut the red), and a touch of purple for the high-relief bits. Then he begins dipping, blending, and stirring everything with what looks like a miniature bubble wand. He dabs test spots on a paper towel. Adjustments are made. (Turns out I have a lot of yellow in my skin.) Then he smears a streak of the final product on my breast and asks me if the color looks right—though I can tell he’s doing so purely out of politeness.

As he fires up the needle, Myers warns that it might sting and instructs me to tell him if I need a break. For a split second, I wonder if maybe I should have just colored in my own nips at home using my kids’ markers. (I was pretty sure they had a red and a green—maybe even a teal.)

But then I thought: How much worse than a bikini wax can it be?

• • •

Chatting up the ladies while he works is a key part of Myers’s job—another way his new persona departs from the old one. “Tattoo artists notoriously do not have a good bedside manner,” he says.

Myers, by contrast, has to be exquisitely diplomatic because many of his customers have been through months of medical—and personal—hell. “You hear the most heart-wrenching stories of ‘Oh, my husband hasn’t even looked at me since I was diagnosed.’ You feel like, ‘Wow. What kind of an asshole is that?’ ” says Myers. “One lady said she was in the operating room with her mom. She comes out and goes home, and her husband left while she was having surgery!”

Asked how he responds to such tales of woe, he says: “I didn’t say anything other than ‘Oh, that’s awful. I’m sorry to hear that.’ But I’m like, ‘Jesus Christ, send him down here and I’ll beat him up,’ you know?”

Myers has an even tougher time holding his tongue when women speak of bullying surgeons who make them feel as if they had no say in the reconstruction process: “I really ought to write a book, because so many times I hear women complaining about their doctors or the way they weren’t informed about what was available to them until it was too late and they’d already had their surgery.”

And do not get Myers started about the number of botched reconstructions he sees: “Oh, my gosh—it happens all the time.” He drops his face into his hands. “It’s just so sad.”

Sloppy incisions, poorly fashioned or unevenly placed faux nipples, slapdash tats—visions of boob jobs gone awry eat away at the man. At one point during our talks (not while he was inking me), he leapt from his armchair to join me on the sofa.

“Look at these!” he exclaimed, holding up his phone and whipping through photo after photo of jagged scars and misshapen breasts. “And these are just from February!”

For the most part, if a woman expresses contentment with her new assets, Myers keeps his opinions to himself—even if he considers the work subpar. But in some cases, the canvas he confronts is so problematic that he has to send a woman back to her doctor for further corrective surgery before he can work on her.

This, needless to say, doesn’t go over well.

“The doctors weren’t happy and called me to let me know that,” he says. “They’re telling me, ‘How could you tell my patient that I did this wrong?’ I’m like, ‘Because you did, man! Because she’s sitting right in front of me and I’m telling you they’re not in the right spot!’ ”

Now and again, Myers has been so outspoken that women have changed doctors after seeing him. That risks crossing the line into dispensing medical advice, says one plastic surgeon whose colleagues have had patients abandon them. While Myers is a genius when it comes to tattooing, the doctor adds, he doesn’t appreciate all the variables that affect results—everything from patients who smoke to those with severe radiation damage to breast surgeons who leave behind a mess of scars for plastic surgeons to clean up.

That said, Myers does have a unique perspective, because “he sees everybody’s patients,” says Gedge Rosson, a plastic surgeon at Johns Hopkins (who jokes that he has happily stayed on Myers’s good side). “Some people out there are definitely doing a bad job, and he does want to out them.”

Increasingly, Myers feels moved to share his views with the broader medical community. In a speech Shockney arranged for him to give to the Academy of Oncology Nurse & Patient Navigators last year, he made known his (strong) opinion that the continued use of dermabrasion tattoos is a “travesty.” Don’t waste patients’ time and money, he urged the nurses. “Just say no.” (“They were blown away,” says Shockney.)

Now Shockney is working to arrange for Myers to do grand rounds with Johns Hopkins surgeons. (He has been asked to do something similar with residents at Georgetown University Hospital.)

Myers himself is thinking even bigger about how to expand access to his unusual talents. He’s in the final stages of launching a nonprofit to provide free nipple tats to survivors unable to afford reconstruction. And in late June he met with breast-cancer philanthropist Dee Dee Ricks to discuss the possibility of doing pro bono work in Harlem.

Myers’s dream? To travel the country—the world, really—tattooing nipples on impoverished women.

• • •

In mapping the future, though, he faces one inescapable, increasingly urgent question: Whom will he pass the needle to—and when?

Every speech the tattooist gives means time away from his studio—and the long list of women clamoring to see him. Because there’s an insatiable demand for his work, there’s by extension a need for him to train others. According to Rosson, “there really should be a Vinnie in every major metropolitan area.”

But although he has mentored a handful of artists, Myers is loath to school aspiring nipple specialists en masse. “The problem is I have no way to guarantee that the people I teach really know what they’re doing,” he says. “Every single student you have can’t be the best scholar in the world.” (Nothing upsets an artiste more than the idea of a horde of mediocre dabblers using his name as an imprimatur.)

For now, Myers’s plan is to run the studio for another decade, then turn the business over to his 19-year-old daughter, Anna, whom he began grooming recently. “But I’m probably not going to be able to stick to the plan,” he concedes. “I’m not going to be able to just close the door and leave, I’m sure.”

I’m good with that. My hour under Myers’s needle wouldn’t rank in my top 1,000 most pleasant sensations, but I wouldn’t call it excruciating. And the finished product? A thing of beauty that I challenge anyone to distinguish from the genuine article. (No. Not literally. That would be awkward.) I would happily recommend him to others. And you can bet that when it comes time to trade in my implants for a newer model, I’ll be looking to get my Vinnies a touchup. I just hope there won’t be too long a wait.

Michelle Cottle (@mcottle on Twitter) is senior writer for National Journal. This article appears in the September 2014 issue of Washingtonian.