Even the guy who runs the schools has something to learn. When Joshua P. Starr, superintendent of Montgomery County Public Schools, arrived in 2011 from Stamford, Connecticut, he led with his ideas for reform, pushing for fewer standardized tests and more technology in the classroom and looking into changing the time of the morning bell.

Though the 45-year-old former director of accountability for New York City’s public schools has remained outspoken and widely popular, he’s also been schooled in the practical problems of aging mobile classrooms, a minority achievement gap, and the limits of even a $2-billion budget.

We talked with Starr shortly before he went to the Montgomery Board of Education in October to ask for $220 million, not for pet projects but for school construction to alleviate crowding.

At back-to-school night, parents across Maryland were exposed to teachers’ anxiety about the Common Core, the new competency standards the state adopted last year. How should they feel about the Common Core?

When I talk to parents, I say, “Look at what we’re actually asking your child to do.” I collect old textbooks, so I’ll show them how an 1861 math problem is very similar to a 2011 math problem on the Maryland School Assessment. Then I show the same long-division concept on the test sample for the PARCC [Partnership for Assessment of Readiness for College and Careers]—the new test aligned to the Common Core. When people see that, they say, “Oh, wow, that’s a much better question. Now I get it.” The Common Core has been so bastardized and convoluted by all of the misguided policies that people associate with it, like the linking of standardized-test scores to teacher evaluations.

Speaking of which, you’re now getting pressure from the state to include more test scores in teacher evaluations.

We’ve always been able to do that. We absolutely use student achievement data in the evaluation of teachers. That said, the science linking individual student test scores to individual teacher evaluation just isn’t there. There’s no research that backs up the idea that that’s what standardized tests should be used for.

After you started this job, you wrote a piece for the Washington Post proposing a nationwide three-year moratorium on standardized testing. Do you still think you were right about that?

Absolutely. Look at the number of people who have come over to that idea. A few months ago, Secretary of Education Arne Duncan said we have too much focus on tests.

What’s your ideal testing scenario?

I don’t believe there should be no testing whatsoever. There’s got to be a reading assessment at the elementary level, to understand school performance. At the high-school level, it’s become high stakes for kids, which can be problematic, but you need high-school assessments of some sort. But we can use Advanced Placement; we can use the International Baccalaureate. I don’t think we need testing at the middle-school level, but I do think ninth grade is so critically important that there needs to be some external measure. If you’re not successful in ninth grade, your chances decrease significantly.

A recent county report found a widened achievement gap between high- and low-poverty schools and increased racial and ethnic stratification in the high schools. How should we think about that?

That report served a purpose for whoever commissioned the report, but it’s not news to us whatsoever. The demographics have changed in Montgomery County pretty considerably. We have more poor kids than DC Public Schools has kids—52,000 poor kids, and we’re growing by 2,500 or so a year overall. In kindergarten through second grade, our Hispanic population is equal to or slightly above the white population. We’re at the front of the trends in terms of a changed America—we’re the demographics of 2042.

Before I got here, I said, “We’ve been to the moon. Now we’ve got to get to Mars.” Are the things that you did to get to the moon going to take us to Mars? You don’t need freeze-dried Tang.

We’ve done really well in a lot of respects. Our AP scores, our graduation rates, our SAT scores for African-American and Latino kids far exceed peer groups in other parts of the country, but we still have this big gap.

Is one solution to change the actual demographic makeup of the schools through school choice?

We recently put out a request-for-proposal for a major study of our choice processes. I was superintendent in Stamford, Connecticut, a tenth the size of Montgomery County but almost the same demographics. We had a rule that said every school must look like the district as a whole, within 10 percent. We don’t have that in Montgomery County.

We also don’t really have a theory, frankly, about why we should have choice. Some places do it because they have a market-based approach: Competition increases performance. Some do it because they want demographic balance.

Our study is going to be a major, multi-year process, so we can say as a community, “What do we want?” Do we want demographically balanced schools? There are African-American and Latino, white and Asian people who say, “No, I want strong neighborhood schools.” And there are African-American, Latino, white, and Asian people who say, “Nope, we should balance it out demographically.”

As superintendent, I’m a steward of the community’s values. I can push, cajole, I can teach. But ultimately communities have to decide.

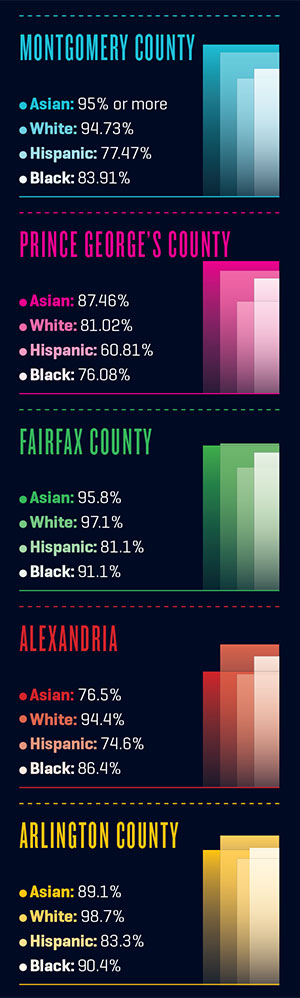

Minding The Gap

With some of the most successful public schools in the country, the Washington area’s most stubborn educational problem is an achievement gap between white students and the largest minority racial and ethnic groups. Here’s how our counties compare, measured by high-school graduation rates.

—John Scarpinato

Do you think that 10-percent rule was good for Stamford?

Yeah, absolutely. The flip side is just because you have desegregated schools doesn’t mean you have integrated classrooms. You may have a school where the demographics are balanced because they have a highly gifted class in there, or two, that are mostly white and Asian. The school may look more balanced, but the classes aren’t necessarily.

Is it your job to try to keep that from happening in Montgomery County?

Absolutely. We do a comprehensive view so we can improve or increase the number of underrepresented kids. We say to our principals, “Show me how you are increasing the number of kids who are taking Advanced Placement classes.” That’s something you address. But there are strict criteria for gifted classes, which are different than Advanced Placement classes. The policies and practices around who is identified as highly gifted don’t necessarily allow for that.

Many of the most successful DC public schools are charter schools. Would students in Montgomery benefit from more charters? Is that part of school choice?

I have nothing against charter schools, but they’ve been no better than traditional public schools for the most part, in some cases worse. We’re turning [public] Wheaton High into a school organized around problem-based learning strategies. The teachers are leading the effort. Same with our alternative schools for youths at risk of not graduating. I sent out a call to everybody in the district saying, “I need the best teachers to go and work at alternative programs, and I need the people who are passionate about our most vulnerable kids.” We had 91 people show up at the hiring fair for it. That’s charter-like, in the sense that it’s an innovative model.

If I were a superintendent in a different context, I might look at it differently. But it’s just not really that applicable here.

A recent push to change the start time for high schools foundered. What happened?

I’d like to change the start times. We start school too early. We did thorough analysis, and the best option would have cost $25 million per year, because we’d have to add buses. I can’t ask the county for $25 million more. The board asked me to see if we could do a $10-million option. I should have the results of that soon. What I won’t consider is the no-cost option, just flipping the start times of elementary and high schools. Then I’d have elementary kids at bus stops at 6:30 in the morning.

I’ll bet you didn’t think you’d be managing a bus system when you started your education career.

Health insurance, real-estate management, transportation—they don’t teach you that stuff in superintendent school.

Four out of five Montgomery County students didn’t pass the most recent algebra final exam. Why?

The exam passing rate is not the right metric. You don’t necessarily have to pass the final exam in order to pass the course. In May, I was in the bagel store and behind me was a sophomore talking to his dad about his upcoming exams. He said, “Yeah, I really don’t need to take the biology one—I’ll do fine, but I’ve really got to focus on Spanish.”

So a kid will fail the biology exam, or the math exam, because he doesn’t need it to pass the course with a B or an A. That gets calculated into the failure rate, but it may be that the kid just hasn’t taken the test.

I don’t want to say, “Oh, we don’t have any problems in math—it’s all BS,” because we do. We’re not where we need to be in mathematics achievement. Too many kids were accelerated too quickly in mathematics. I appreciate the intent, but what we hear from teachers is that a lot of kids just didn’t have the fundamentals. And we have an aggressive approach to making sure our kids get support. In fact, after we intervened this summer, only 280 or so kids didn’t pass the course.

You have laptop computers now in the third, fifth, and sixth grades. What does a third-grader do with a laptop?

Have fun, engage in deep work. They access different kinds of materials in different ways. It’s writing, it’s math—all the same stuff that’s not on a laptop, but they’re able to express what they learn in different ways, whether it’s videos or whatever the teacher dreams up.

You go to work not far from where Congress writes the nation’s education laws. What would you ask them for?

Testing is the major thing. We’ve also got to do something about the way schools are funded. The feds need to hold states and school districts accountable for building capacity. Instead, there’s this huge overreach—everything is put on individual schools and teachers. Where is the accountability for school boards, teachers’ unions, funding?

If it falls under superintendents, that’s fine. I embrace that.

Kevin Carey (carey@newamerica.org) directs the education-policy program at the New America Foundation. This article appears in the December 2014 issue of Washingtonian.