Forty years ago, it was disco and bell bottoms, the city was falling to pieces, hostesses from Spring Valley to Cleveland Park were putting joints in silver dishes on their coffee tables, the Country Gentlemen were playing bluegrass in Arlington, and people were discussing moving the capital to Kansas. It was an era without a definition, then or now. Washingtonians tend to measure history in myth-driven increments: the romance of Camelot, the fury of Watergate, the Reagan Revolution. But we don’t even have a name for the period, this historical cul-de-sac, between Richard Nixon and Ronald Reagan.

Nowadays, standing on the rubble of our own quarrels and dysfunctions, some would have us look back and imagine that it even featured a brand of goodwill, when Democrats and Republicans, instead of grabbing the Thursday-evening plane for home, stayed in town and dined together. In our agita over polarized government, it’s tempting to cast a backward glance on the era as an unlikely example of better behavior.

Look elsewhere. Far from being a political paradise, Washington had gone moribund. Six years after Martin Luther King Jr.’s murder and the burning and looting, nothing had been repaired. Burned-out buildings abounded. The murder rate had ticked upward. DC was bleeding population. As for race relations, there were none to speak of. Federal Washington was a shell-shocked and angry place. A month after taking office, Jerry Ford–the Nixon-appointed, just-like-the-folks-next-door President–split the political city into irreconcilable bitterness by granting Richard Nixon a pardon. As far as Democrats were concerned, the era of good feelings was over before it had begun.

Within 17 days in September 1975, two women tried to kill Ford. Faulty weapons–one without a bullet in the chamber, the other in slight misalignment–saved him, but the incidents were in sync with the moment, when Washington and the world were suffering from the wobbles. The Vietnam War had ended in acrimony and shame. A bomb blew the bejesus out of the State Department. A score of rooms and several elevators were put out of commission by the bombers, a cadre of college-educated youths from the psychiatric wing of the American left.

Americans faced with rising prices were told inflation could be controlled if everyone wrote the President that “I enlist as an inflation fighter and energy saver for the duration.” Alan Greenspan, then chairman of the Council of Economic Advisers, remembered thinking, “This is unbelievably stupid.”

• • •

In real life, the political socializing that people so miss nowadays wasn’t so impressive. Cavedweller Washington was melting away. Informality was seeping across the door sills. The young men still wore ties, but their sideburns were long and bushy and they called you by your first name. Yeats was quoted at dinner parties: “The best lack all conviction while the worst are full of passionate intensity.”

The highly placed who always knew what to think didn’t know what to say now. In the clamor of defeat at war and nudity at home, palsy had weakened the once-sure hand of the master class’s grip on history. The anchors of the expiring social order were Kay Graham, owner of the then all-powerful Washington Post, a Democrat, and Alice Roosevelt Longworth, the Republican daughter of Teddy Roosevelt. Once a month, Mrs. L. gave a dinner party at her home, a large rowhouse on Massachusetts Avenue. The menu was always the same–“It’s the only thing they know how to cook,” she told me–but hers was the most wished-for invitation in town, short of dinner at the White House. At Mrs. L.’s, the old ways were kept up–men in dinner jackets, ladies retiring after dessert to leave the men to their cognac and cigars.

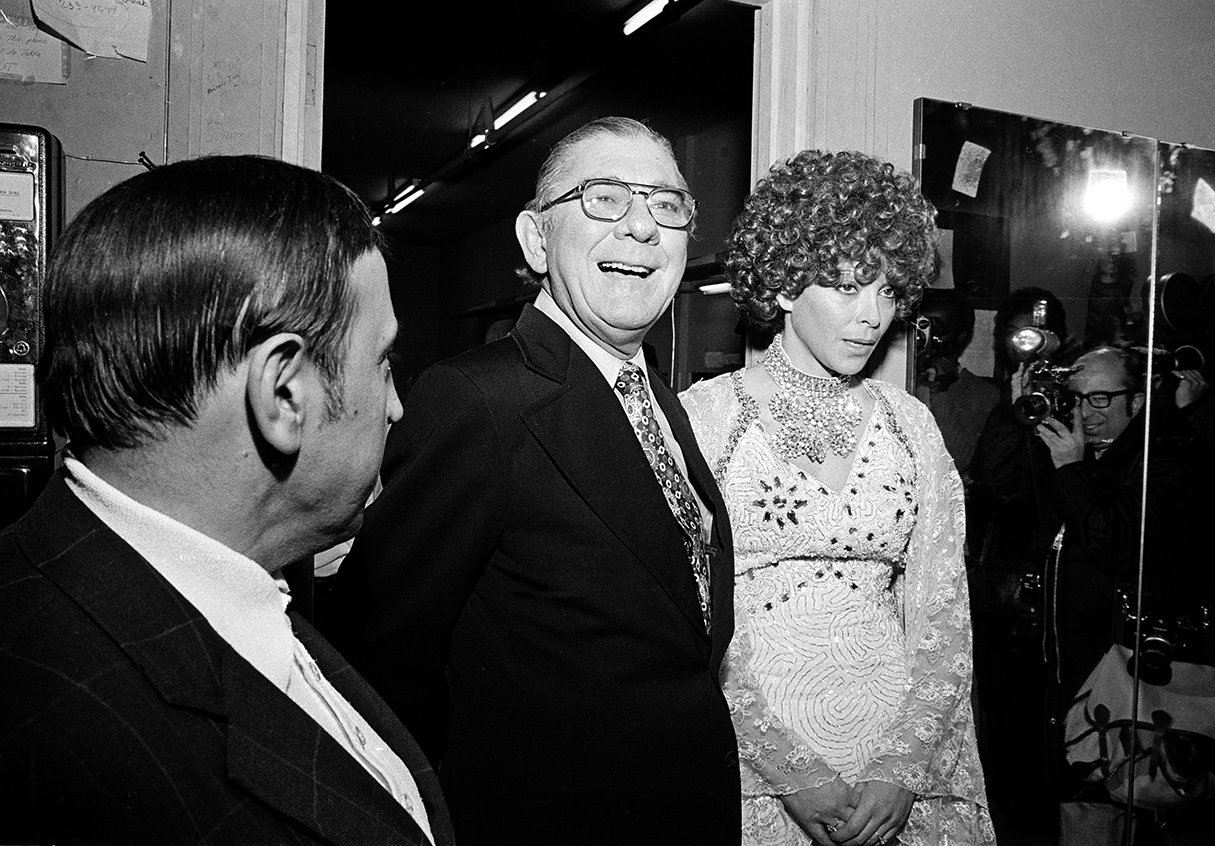

The powerful behaved as if there were no consequences. Wilbur Mills kept his job as chairman of the House Ways and Means Committee after the police stopped his car late at night and his passenger, Ms. Fanne Foxe, a professional ecdysiast, escaped Mr. Mills’s automobile to dive into the Tidal Basin, whence she was extracted and trundled off to St. Elizabeths. A few weeks later, the congressman did lose his job when, drunk, he lurched onstage, interrupting Ms. Foxe’s performance at a Boston burlesque house.

It was a louche interval in the city’s and the nation’s sociopolitical history. Sexual harassment wasn’t yet a career-ender. Senator Bob Packwood had a reputation so rank that staff directors in senatorial offices and lobby shops advised female employees not to meet with him alone. Twenty more years rolled by before Packwood was driven out of the Senate.

At the other end of the masher/gallantry continuum was Gillespie V. (Sonny) Montgomery, a bachelor congressman from Meridian, Mississippi. Every night, he had a different date on his arm. So good was the word of mouth on Sonny that women were said to connive for a date with the true gentleman from the 3rd Congressional District.

• • •

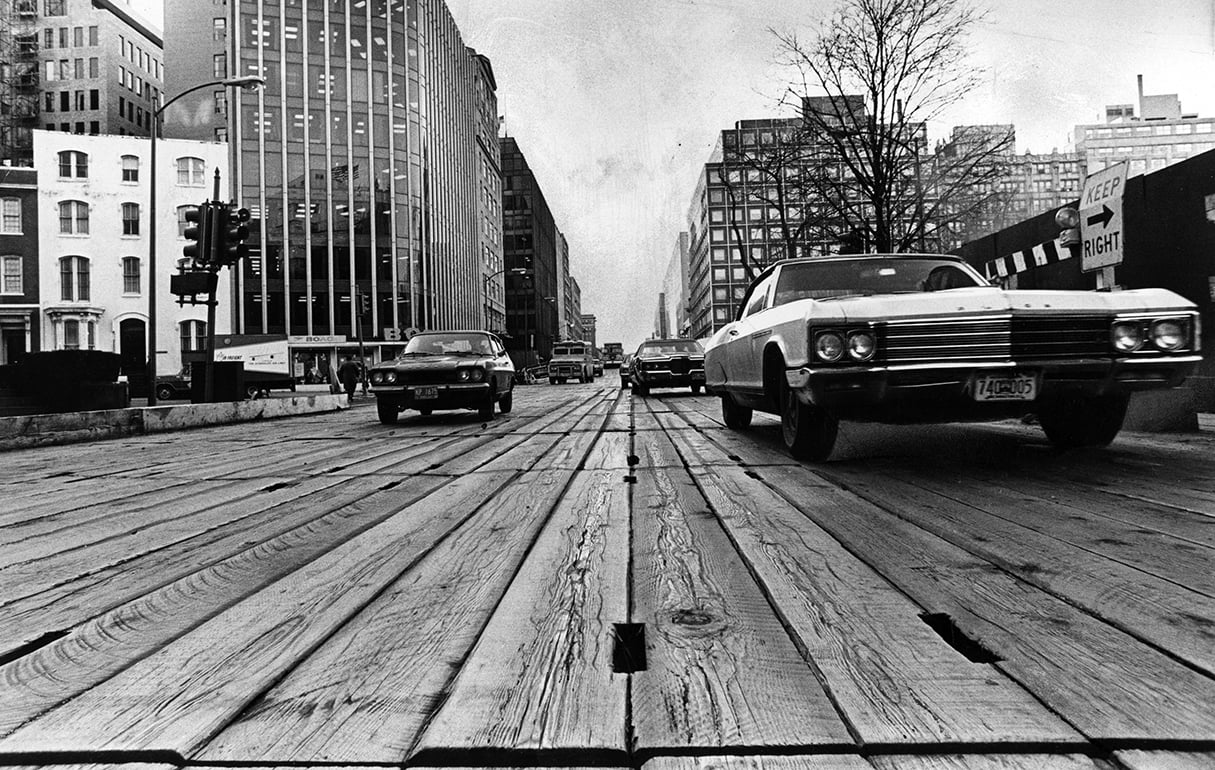

Modern Washingtonians who wish their party elders could ride herd on the compromise-averse true believers probably wouldn’t like what that looked like in practice. Influence peddlers understood that much of Congress stays while Presidents come and go. But even for them, Jimmy Carter’s election was unsettling. After his inauguration, he and Rosalynn broke with protocol by getting out of their car on the parade route and walking amid the people past the souvenir stores and hamburger stands that were Pennsylvania Avenue 40 years ago.

This rural man in an urban age was the kind of President people said they wanted–until they got him. A puritan in a licentious time, Carter confessed in a Playboy interview that he had “committed adultery in my heart many times.” Among Washington elites of all partisan stripes, he was scorned as a hick.

Carter had the bad luck to be a practicing Christian when the river that once had been mainstream Christianity was turning into a sandy gulch. Closer to Jeremiah than to chief executive, he told his people that what he had to offer them was “not a message of happiness or reassurance but it is the truth and it is a warning.” But members of his administration, to their unhappiness, were said to be out interacting with non-politicals in that fabled real world. It was whispered that Hamilton Jordan, Carter’s chief of staff, was up in New York City in the VIP basement of Studio 54, the center of degeneracy, sniffing cocaine.

A group of Republicans–playing ironically on ideals of friendship and loyalty–may have brought an end to Carter and this interstitial moment in US history. David Rockefeller, head of Chase Manhattan, one of the country’s largest banks, and Henry Kissinger, Nixon and Ford’s Secretary of State, took it into their heads–with a few other highly placed, rich men–to help a friend, the deposed shah of Iran, Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, King of Kings and Light of the Aryans. Dying of lymphoma, the shah, who’d been expelled from Iran and was unwelcome elsewhere, was begging to be let into the United States.

Assailing the White House with visits and letters, Kissinger, America’s Doktor of Realpolitik, went gooey pleading for the useless shah. Given what the King of Kings had done for the USA in the past, Kissinger begged that he “should not be treated like a Flying Dutchman who cannot find a port of call.”

Kissinger, who had backed dictators and despots when it suited him, had forgotten there was no gratitude in politics, but he got his way. The shah was let in, the US Embassy in Iran was stormed, its personnel were taken, and Jimmy Carter spent the last year of his term embarrassed, failing to rescue the hostages, losing respect and popularity.

In the end, having crawled off to Egypt, the Light of the Aryans was extinguished, Carter was trounced in the election, Ronald Reagan–atop his shining city on a hill, preaching hope and happy endings–commenced a new era.

Nicholas von Hoffman is a former Washington Post reporter. His most recent book is “Radical: A Portrait of Saul Alinsky.”