Washington residents who relied on the NextBus application for information about when their buses would arrive felt left in lurch this week as the popular software stopped functioning for buses operated by the Washington Metropolitan Area Transit Authority. NextBus, the company that had provided Metro riders with updates since 2009, has been replaced as the preferred vendor for bus-arrival predictions by OneBusAway, an open-source data project used by a handful of other US transit agencies, including New York’s Metropolitan Transit Authority.

Instead of an app, though, OneBusAway’s product for Metro is website called BusETA, which launched in a public beta last month. The rollout has been a bit buggy—Metro attributes this to a server problem that has been fixed by adding more bandwidth—but one of the overall goals is to eliminate NextBus’s phenomenon of “ghost buses,” or the buses that appeared to be en route but never actually show up.

But just because NextBus is finished here doesn’t mean everyone has to default to a fledgling website. There have been, and continue to be, numerous other apps that provide bus predictions using the same data upon which NextBus relied. Metro offers an open application-programmer interface that any developer can tap to create software that tells users when buses or trains will arrive. A search for “DC bus” in Apple’s iTunes store turns up dozens of free and paid apps, many of which existed alongside NextBus for years. They all do effectively the same thing; the only differences are in the programming.

But just because NextBus is finished here doesn’t mean everyone has to default to a fledgling website. There have been, and continue to be, numerous other apps that provide bus predictions using the same data upon which NextBus relied. Metro offers an open application-programmer interface that any developer can tap to create software that tells users when buses or trains will arrive. A search for “DC bus” in Apple’s iTunes store turns up dozens of free and paid apps, many of which existed alongside NextBus for years. They all do effectively the same thing; the only differences are in the programming.

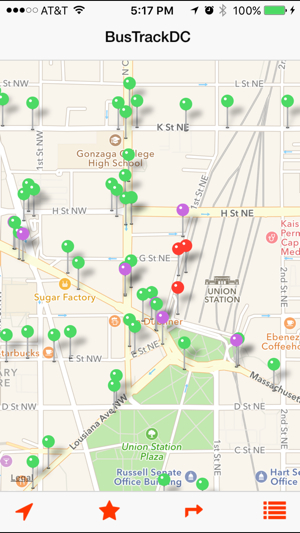

“There is only one source of this data, and that’s Metro,” says Jason Rosenbaum, whose free app, BusTrackDC, has been downloaded about 40,o00 times since he created it in early 2013. “People can interpret it in different ways and add their own special sauce.”

Metro’s API allows developers to make different “calls” to produce data points concerning buses and trains, which can then be turned into predictions based on time and location. Every bus stop has a numerical identity in Metro’s system, and buses are equipped with GPS devices. “One of the calls you can make is, ‘At this stop, when will the next buses arrive?’,” Rosenbaum says.

Ghost buses might be tougher to eliminate than a simple software switch. Sometimes, Rosenbaum says, they can happen because of human action.

“Sometimes I’ve seen ghost buses which are buses that are out of service but didn’t turn off their GPS transponders,” he says. “Another is this prediction piece. Let’s say a bus is 20 minutes from you, but it breaks down, gets in an accident. It might take some time for that transponder to go off. At some point it drops off but people see it as a ghost bus.”

BusETA is designed to eliminate the ghost buses by reverting to routes’ schedules if GPS locations become unreliable.

But there are other advantages to using an app like Rosenbaum’s over Metro’s new website. BusETA only serves up bus information, while an outside app can integrate Metrorail and services operated by other transportation agencies, like the Circulator routes operated by the DC Department of Transportation. Rosenbaum says his next update will add in the DC Streetcar.