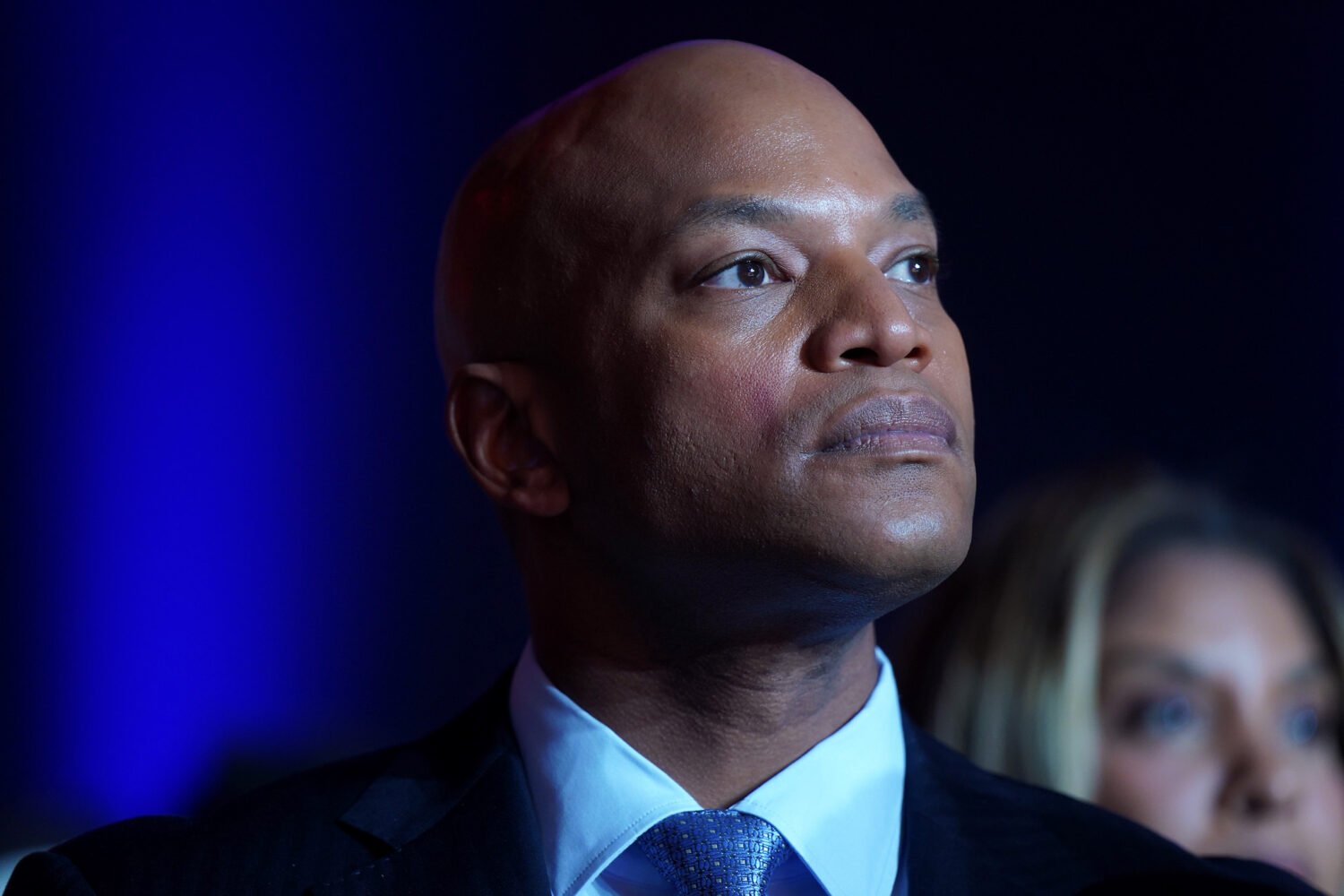

One night earlier this school year, Bonnie Fogel, founder of Imagination Stage, stood in the theater’s hallway greeting donors and politicians, children and parents.

It was the evening of a premiere, and the entry was packed. Slipping away from the crowd for a moment, Fogel ducked into the toy shop that greets each child at the entrance and ran her hand along the dress-up costumes and baubles.

Fogel knows children like to try on identities, to test the world. She certainly gets how they see it: a little dark sometimes, very light at others, always full of possibility. And she has surrounded herself with artistic visionaries who refuse to make the company’s shows simplistic or blandly sweet.

Remember The Parent Trap? Imagination Stage’s rendition last season scrapped the Disney modification of the Erich Kästner book about identical twins whose warring parents Solomonically divide the family. In other versions of this show, the parents (miraculously, ridiculously) reunite. In Imagination Stage’s Double Trouble, they stay split, but the plucky protagonists gain the sibling relationship they had long been denied.

This year, in Jack & Phil—Slayers of Giants-INC, the two boys of the title hope to rescue Jack’s home from foreclosure. The result was a sleek reconsideration of the age-old beanstalk story for the Twitter era. Finding a giant’s gold leads to a 24-hour media barrage during which Jack embraces celebrity thanks to Phil’s feats of ingenuity without affording him credit, until he realizes that friendship trumps fame.

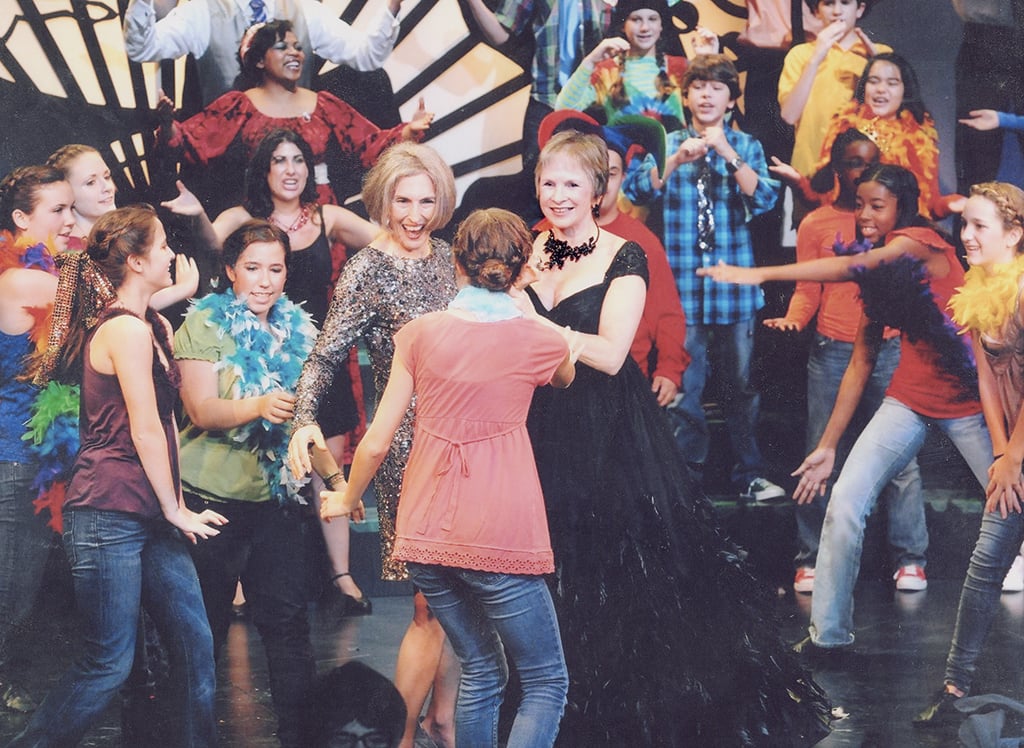

This is theater for the under-12 set, to be sure—but it’s family fare that all ages can genuinely relish. In Imagination Stage productions, sophisticated dialogue keeps adults as entertained as their charges. The company is known for capturing a kind of magic that feels tangible, possible—and not remotely childish.

Indeed, little separates many of the shows from the best adult theater in Washington. Imagination Stage commissions new work from accomplished playwrights and has staged 40 world premieres. Double Trouble’s score had some of my audience-mates wondering when the cast album would be out. Another recent show, When She Had Wings,ingeniously used actors for entirely manmade sound effects straight out of old-time radio. The elaborate set would have fit right in at Arena Stage.

Bonnie is a woman of great vision. Each [Imagination Stage] story has real integrity, real characters whose actions have real consequences…It is not fluffy entertainment—it is entertaining and captures imaginations, but the theatrical integrity is always present.

This year, Fogel’s theater was nominated for nine Helen Hayes Awards—Washington’s most prestigious theater honor—and was recognized in multiple unrelated-to-age categories such as Outstanding Original Play alongside the Kennedy Center and Shakespeare Theatre Company.

This month, Imagination Stage presents a collaboration with the Washington Ballet. Septime Webre, the ballet’s artistic director, approached Fogel about a new interpretation of Hans Christian Andersen’s The Little Mermaid, their second joint project.

“Bonnie is a woman of great vision,” says Webre. “Each [Imagination Stage] story has real integrity, real characters whose actions have real consequences. . . . It is not fluffy entertainment—it is entertaining and captures imaginations, and it’s a lot of fun, but the theatrical integrity is always present.” This mermaid walks away from Disney, and the theme trends more stranger-in-a-strange-land than rom-com.

In three decades, Imagination Stage has gone from a 17-student afterschool activity to a multimillion-dollar arts-and-education center: Some 42,000 area students visited on field trips last year alone. Its progress would seem unbelievable—until you realize it was Fogel’s vision all along.

“I do remember thinking in my wildest dreams,” she says, “that we would be like the Washington Ballet, with the same standing in the community.”

That’s why those closest to Fogel weren’t surprised that she’s expanding the Bethesda theater’s geographic reach into DC, and, she hopes, beyond the Beltway, too.

But while her drive is well known, her background is not: Fogel, 72, is the daughter of an itinerant English housekeeper and was born out of wedlock. She has no college education, and her family history is filled with secrets and half truths she only recently began to uncover. Hear it and you come to understand that her very identity, and her ascension to Washington institution—a tale ripe for her own stage—may be one of our area’s most remarkable tales of reinvention.

• • •

Fogel’s 1950s English-style cottage is tucked among the mansions of Bethesda, with an actual garden gnome out front and, inside, a tea cozy and other assorted Anglophile knickknacks.

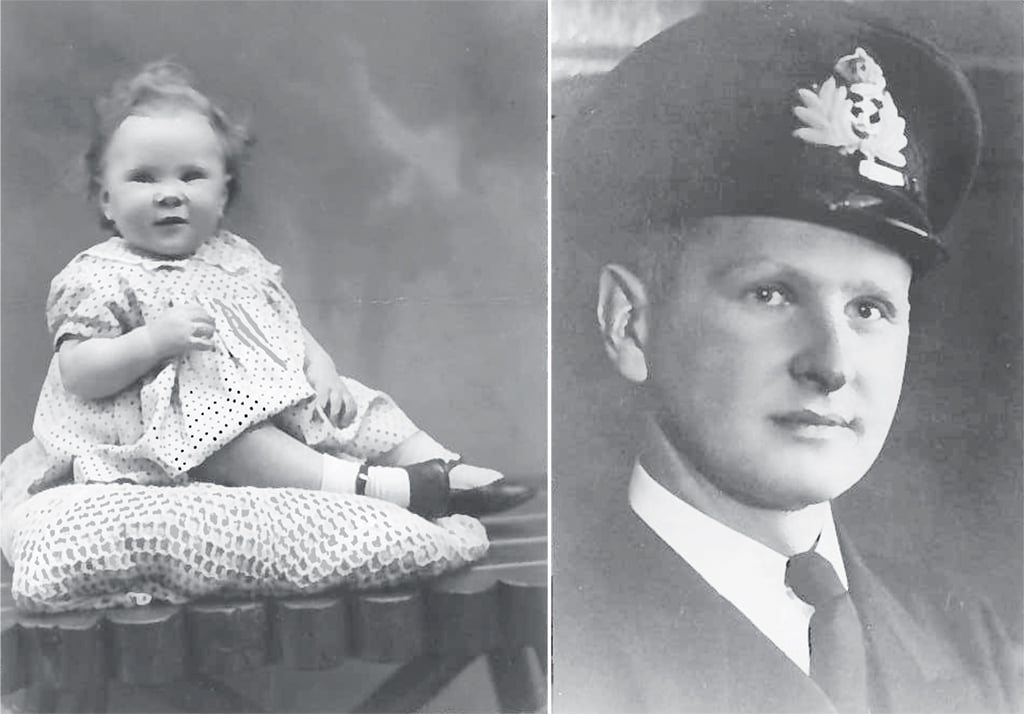

On the entry table is a black-and-white portrait of a soldier. For decades, this was all Fogel knew of her father.

Her mother, Joyce Rochefort, met Tom Unwin, a recent Czech émigré, during World War II. Both were working in an armaments factory in the British city of Wells. (“That’s Wells, dear,” Fogel says in her plummy Queen’s English, spelling it out. “Not Wales.”) Joyce had two girls at the time, ages two and four; their soldier father was listed as missing in action.

Joyce and Tom were sweet on each other; before long, she was pregnant with Bonnie. But Tom, too, went off to war. Then disappeared.

Bonnie was born in 1944. Soon after, Joyce’s first husband—presumed dead—turned up alive. The baby in the bassinet was undoubtably not his. In a rage, he tried to burn little Bonnie with scalding water.

Joyce fled. She dropped the older girls off at a relative’s and stole away with Bonnie. For the next decade, mother and daughter moved from town to town as Joyce scraped by, working as a housekeeper. Her letters to her older daughters were returned unopened. She remarried, but that relationship also turned violent: One night as her stepfather beat Joyce, young Bonnie chased after him with a kitchen knife.

Bonnie began to hear snippets of her family story sometime after she turned eight. Joyce had been the daughter of touring vaudeville actors, raised in an orphanage and foster care—an explanation, perhaps, for her affectless presence, her emotional distance from her daughter.

Joyce told Bonnie her sisters were dead. So was her father, Tom—killed in the war. Apart from the soldier’s portrait that accompanied them from home to home, the man was a mystery, with no past, no biography. Bonnie had so many questions. If her parents were really married, as Joyce had told her, why weren’t they supported by a war widow’s pension? And didn’t her father have relatives?

It was a lonely upbringing. Bonnie surrounded herself with imaginary siblings and pets. She yearned for family. One day around her 12th birthday, she got her wish, in a manner of speaking.

“Do you remember the sisters I mentioned?” Joyce asked her when she got off the school bus. Bonnie did. “Well,” said Joyce, “one is at the house now.” Sally, one of her daughters from her first abusive husband, now a teenager, had tracked them down. Bewildered, Bonnie was nevertheless happy to have a sister.

Tossed between schools, Bonnie was rarely in one place long enough to focus on her academics. Joyce finally sent her to boarding school for high school. There, Bonnie immersed herself in the theater and athletics. Performing suited her.

There was no money to continue at university. Bonnie went into a managerial program at Marks & Spencer, the department store. She met an American grad student named Richard Fogel, married him, and eventually resettled in Bethesda in 1969. She was already a mother, of a boy and a girl, when she learned that Joyce’s untruth about the death of Bonnie’s sisters wasn’t her only foundational lie.

It was 1980, and Bonnie had flown back to the UK for an aunt’s funeral. There, a family friend told Bonnie her father not only hadn’t died in the war; he wasn’t dead now. “I was terrified,” she recalls. “I was afraid he wouldn’t be what I needed him to be, which was the kind of person you wanted to discover.”

In that pre-internet era, it took two years to track Tom Unwin down in Africa, where he was working for the United Nations. When they finally met in London, Bonnie Fogel was 40. He told her he hadn’t known Joyce was pregnant when he went off to war—Bonnie, he insisted, was a total shock.

Unwin, Fogel came to learn, had had two other children, a boy and a girl, after the war with two other women. They were off-limits, he said. Fogel abided by the rule, but at the end of her father’s life, she insisted on meeting her sister. After he finally relented, not long before his death in 2012, Bonnie’s sister Vicky Unwin revealed another dramatic twist to Bonnie’s backstory.

“He was a chameleon, my dad,” says Vicky by telephone from her home in Singapore. “He was a very great linguist who spoke 11 languages fluently. A very clever man.”

Tom Unwin, the dashing émigré for whom Joyce had fallen at the factory in Wells, was really Tomas Ungar, son of Czech Jewish intellectuals. His mother had fled with him, but his extended family had been murdered in Nazi death camps.

As a young man in England, Unwin believed that his Jewish heritage had only brought pain. So he buried it—and reinvented himself as an Englishman, an identity he wore for the rest of his life.

• • •

Rather than destabilizing Fogel, meeting her father was empowering.

The two formed a friendship that spanned more than 25 years. Getting to know him, and then Vicky, was grounding. They were stable people, and expressive. They shared her love for intellectual expression, for creativity.

After all those years of shifting stories, swirling questions about her identity, Fogel finally had answers. “It made me more confident,” she says. “It’s like when you’re in love and you can suddenly do anything.” This new faith in herself propelled her will to build and expand Imagination Stage.

In the 1970s, Fogel had become bothered by what she saw as “very limited opportunities for creative expression” in her young children’s school, “whereas I had grown up in schools where drama, music, literature were somehow seamlessly integrated into the school day.” She and another parent founded an aftercare arts program and drama workshop at Whittier Woods Elementary School in Bethesda in 1979.

Her vision was ambitious from the outset. Fogel decided that Bethesda Academy of Performing Arts (BAPA), as she first called it, should put out professional productions and nurture original-play development. Over time, the aftercare program became a full-fledged theater-and-education center, offering summer camps, bringing local school districts in for shows, and creating developmentally appropriate, yet curiously fascinating, toddler fare.

Under artistic director Janet Stanford, who’s been involved since 1984, the material produced isn’t saccharine. “I believe you should never condescend to children,” Stanford says. “You learn to have an emotional landscape as a child, when you don’t have barriers—you feel things more strongly in your early years, and theater should be a place where you experience them. Then when the first things go wrong in school, you don’t feel completely alone, because you already saw a character survive it.”

Fogel isn’t the dramaturge. She doesn’t attend rehearsals or give notes to the director. Often, she doesn’t see a play till opening night. Her creativity as executive director, however, enabled the Stage to evolve. In the late 1980s, for example, she decided there were Washington children she wasn’t serving well enough.

“She had had enough kids with what are called ‘invisible disabilities’ like dyslexia or even hearing impairments or sensory integration disorders,” says Sally Bailey, now director of the drama-therapy program at Kansas State University. Fogel wanted Bailey to figure out how to integrate all children into classes and performances. The board balked at first. Fogel pushed back. “She said, ‘I don’t know how to do this,’ Bailey recalls. “ ‘You will have to become the expert and tell me what you need.’ ”

That inclusivity remains a core plank of the theater company’s work.

By the turn of the millennium, BAPA had outgrown its space—a former dress shop in White Flint Mall and classrooms in an old school. Fogel, by this time divorced and devoting nearly all her time to Imagination Stage, learned that Bethesda planned to build a new parking garage to anchor its northern shopping district. The word on the street was that proposals were welcome for imaginative uses of otherwise eyesore real estate. She thought: Well, why not a theater? It would consolidate all of BAPA’s programs under one roof and completely reinvent the concept of a parking garage.

Fogel carefully stacked her board with architects, developers, city planners, and fundraisers. She tapped into that expertise and leveraged her connections to local politicians and urban planners—then proposed a state-of-the-art children’s theater and education center. Winning bid in hand, she proceeded to raise $12 million for the facility and simultaneously swelled her annual budget from $850,000 to $4 million. (It’s now $6 million.)

“It was incredible that Bonnie was able to conceive of this once-in-a-lifetime opportunity,” says Robby Brewer, a Bethesda real-estate lawyer who was board president at the time, “but then to also pull off the design, construction, and, most particularly, financing and then, amazingly, grow staff, programs, and business to fit the much-enlarged space—it was three times as much space.”

According to Stanford, Fogel is sometimes so ambitious she can overreach: “She is very entrepreneurial . . . and I will temper that with ‘But Bonnie, these are our priorities.’ Sometimes that means reeling her in a bit.”

• • •

In late 2014, Imagination Stage announced, with great fanfare, the creation of the National Children’s Theatre, a second home for the company on Pennsylvania Avenue in the National Theatre’s Broadway-size space.

Under the deal, 10,000 District public-school students would see shows each semester. But after a single production, the initiative was iced. Calendars collided—the collaboration proved too complicated.

You might conclude from the quick retreat that children’s theater will only ever get so big—that it can never gain major-media reviews or override major-theater scheduling concerns (particularly because the Washington Post recently changed its coverage of children’s theater, replacing reviews of most productions with preview roundups and occasional features). Fogel, though, concedes no such thing.

“I consider it to be a dream deferred,” she says. “It was unfortunate that we were not able to secure the dates we needed at the National Theatre to continue the vision at that venue. With that said, we will bring DC’s schoolchildren to the Atlas Performing Arts Center in 2016.”

After all those years of shifting stories about her identity, Fogel finally had answers. This new faith in herself propelled her will to expand Imagination Stage.

Fogel is routinely described as “tenacious,” so it’s no surprise that she immediately found a work-around. The Atlas, on H Street, Northeast, is a much smaller satellite than the National, but it’s still a strong foothold in the city. “I always regarded her as formidable,” says Atlas executive director Douglas Yeuell, who shares Fogel’s dedication to developing what he calls “arts audiences from womb to tomb.”

To accomplish that, Fogel wants also to go digital and to broadcast her shows in living rooms, schools, and theaters around the country. It’s a plan modeled after the National Theatre in London, which beams its performances into movie theaters globally.

“We want to bring a camera into [the theater],” she says, “not one camera but 8 to 11 cameras to capture it in an entirely new way, so you can watch at home with a completely different experience than in an audience.” She’s excited now, talking about this chance for children everywhere to engage, no matter geography or economic ability. “You could watch it time and time again. It would be, instead of fast food—cartoons and puppets—slow food for children.”

Says Sally Bailey: “Not everyone can have vision, and not everyone knows how to pick the right people…to implement it.” Fogel, she says, has mastered both, and with imagination, too.

Contributing editor Sarah Wildman (@SarahAWildman on Twitter) is the author of “Paper Love: Searching for the Girl My Grandfather Left Behind.”

This article appears in our June 2016 issue of Washingtonian.