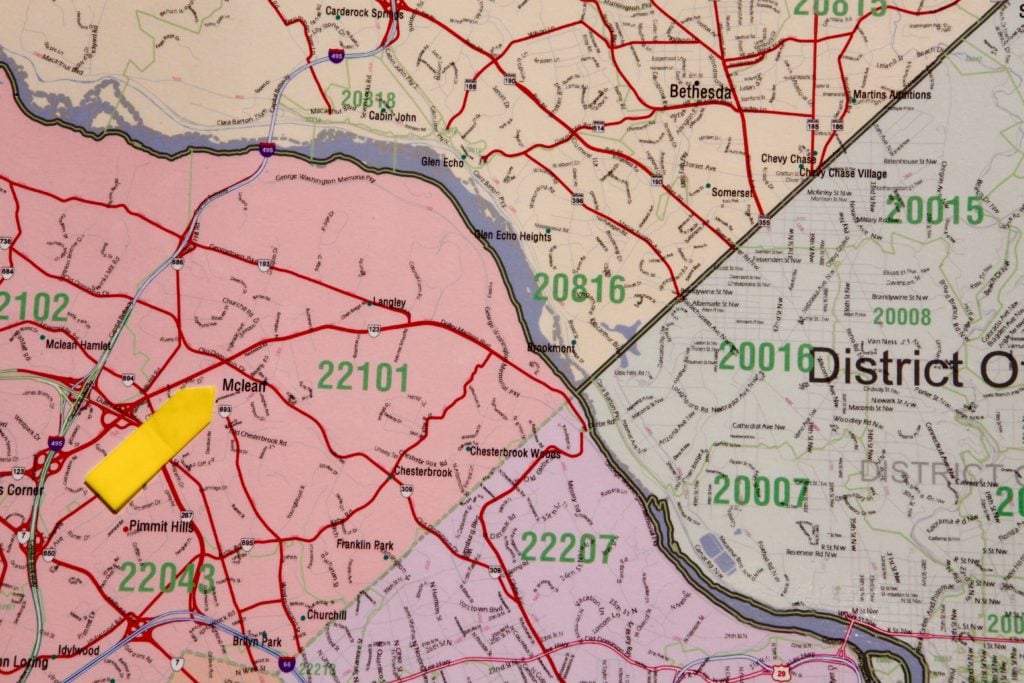

Sue Duncan was roasting a chicken for dinner when she and her husband heard the doorbell ring. It had been a quiet night. Leo Fisher was sitting on a recliner in the living room, reading. It was 6:15 on November 9, 2014, a cool fall evening in McLean.

Sue and Leo were both 61. While they had lots of friends in the area and considered themselves social, they liked to stay in. The couple called each other by the sorts of nicknames people develop over long marriages—Muffin and Pup and Dill and Gee. He addressed her as Muffy sometimes. She called him Pie. Tonight Sue was wearing corduroys, a black tunic over a white sweater, and glasses. Leo wore a dark-brown sweater over a T-shirt he’d bought on a family trip to Turks and Caicos.

Leo got up from his recliner, walked to the door, and opened it a crack. What happened next took mere seconds. A man in a long black jacket shoved the door all the way open and fired a Taser at Leo’s chest. Two darts stuck in his sweater. Leo fell to the floor, writhing. The man bound his hands and feet with zip ties.

“I’m with the Virginia SEC,” the man announced after Sue ran toward him and screamed. “And I’m arresting your husband.”

The man wore an Indiana Jones–style hat pulled down over his face and sported a strange pair of black sneakers, with Velcro instead of shoelaces. He flashed a badge. Sue was recently retired from a career in financial services and knew there was no Virginia SEC—only the federal Securities and Exchange Commission. She began backing up. The man cornered her and bound her hands and feet like Leo’s.

“Why are you here?” Leo managed to say.

“Do you know who the Knights Templar are?” the man said.

“Yeah, they’re a crusading group in like the 12th century.”

“No, they’re a drug cartel. And you sent an e-mail putting a hit on somebody in that cartel for $370,000.”

Leo was baffled. He was an attorney and managing shareholder at Bean Kinney & Korman in Arlington. His firm handled trademark and copyright cases.

“Sir, who are you looking for?” he said. “My name is Leo Fisher.”

“I know,” the man replied, then forced the couple into their bedroom so he could begin the interrogation.

That’s the word he used, interrogation, and that’s what the next three hours felt like. The man said he had their house under surveillance and knew they didn’t go out much. He started asking for details about Leo’s firm, using names Leo recognized. The man insisted someone had “put a hit” on Leo for $27,000. When Leo said he didn’t know anyone who would do that, the man asked, “Didn’t you let somebody go lately?”

Leo had, in fact—a young female attorney.

The man had a lot of questions about this, although he didn’t use her name.

After about 45 minutes, he wandered out of the room and made the first in a series of calls out of the couple’s sight. They could hear him giving curt answers to someone: “Yes. . . . No. . . . Not yet.” One time he said in a bored voice, “Whatever.”

Afterward, the man would return and say he’d been talking to his “partner,” or sometimes his “boss.”

About an hour and a half into the ordeal—it was hard for Leo to gauge the passage of time—the man took Leo into his home office and forced him to log into his firm’s private network. The man could now see its administrative files and client list, a closely held secret. He started typing, searching for something, but soon grew frustrated.

All the while, Sue couldn’t stop thinking about Leo’s heart. Doctors had performed quadruple-bypass surgery the year before. He still took medication. Now he seemed to be having trouble breathing and said he felt as if he were having a heart attack. Sue asked the man to call an ambulance. He said no. A doctor then? He refused. Sue remembered that the chicken was still in the oven and asked to go downstairs and turn the oven off. The man said he’d do it himself.

At one point, Sue started feeling as if she might throw up, and the man cut the zip ties on her hands so she could use the bathroom. From time to time, she would return to it and retch while Leo stayed on the bed. Once she peered around the corner of the bathroom and saw that the man was near the front door, flipping the outdoor lights on and off as if to signal someone. Another time, the front door was wide open and Sue could see him talking to a woman outside.

Eventually, the man said he needed to ask Leo about things he might not reveal in front of his wife. “It’s only for 15 minutes,” the man said, leading Sue to the bathroom. Sue looked at her watch. It was five past 9.

“Are you okay?” she yelled through the door at Leo. “Are you okay, Pie?”

He said, “Yes, I’m okay.”

Leo was looking up at his captor, who had abruptly switched topics. “Do you keep a lot of money in the house?” the man asked. Stacks of $20 bills? Didn’t Leo have $20,000 to $100,000 in cash?

No, Leo said, no stacks of bills, no cash.

Did he have any gold?

No, he really didn’t.

Leo offered to get some cash from an ATM. The man looked to the side and said nothing for 15, 20, 30 seconds. Then, before Leo knew what was happening, the man knocked him onto his back, put a pillow over his face, and cut his throat.

***

The next time Sue called out to Leo, there wasn’t any answer. She opened the bathroom door and saw the man on top of her husband, cutting him and stabbing his left shoulder.

“Muffy, he’s murdering me,” Leo said.

The man laughed. “What is this, the Muppets?”

He sprang off Leo and turned to Sue. In his right hand was a pistol—a Cobra .380, silver with a black stock, four rounds in the clip and one in the chamber. He fired.

Leo watched his wife’s hair fly out, as if blown by a gust of wind.

The bullet grazed her skull, taking a divot out of her scalp. “I felt myself getting up,” she’d say later, “and I knew I was alive.”

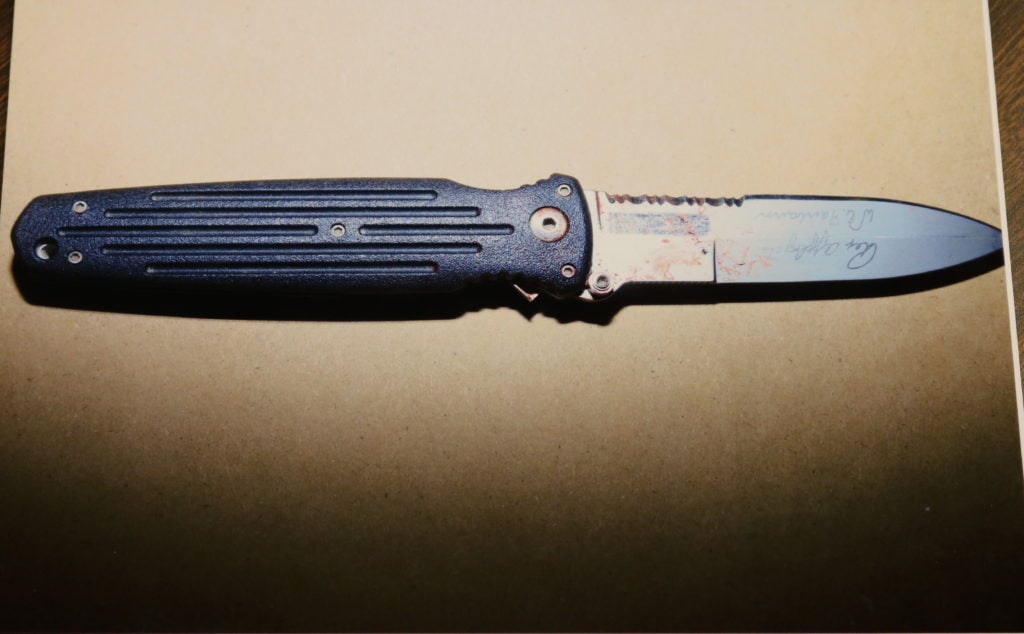

Sue climbed onto the bed and tried to crawl across it to the phone. Suddenly, the man was on top of her and she felt a knife plunge into her neck. He was stabbing her in her neck, on her back, on her shoulders, over and over. She collapsed. The man got off. When she went for the phone a second time, the man stabbed her some more.

Finally, Sue played dead.

The man picked up the spent shell casing. He walked over to Leo bleeding on the floor, kicked him in the head, and said, “You’re going to die,” before walking out of the bedroom.

Muffy, he’s murdering me,” Leo said. The man laughed. “What is this, the Muppets?

At last, Sue made it to the other side of the bed, only to find that the captor had taken the phone. She reached up and tripped a burglar alarm on the wall, and a siren began bleating through the house. She dragged herself to the office—another phone was there. “Hello,” Sue said to 911 at 9:44 pm, giving her address. “Home invasion. Sue Duncan and Leo Fisher. Home invasion. Please come right away. We have two cats. Please save them.” Her glasses were caked with blood.

Leo said, “I love you.”

He stumbled toward the front door and fell in the foyer. After lying there for a time, he thought he saw the flashing lights of a police cruiser. He opened the door, went out to the deck, and begged the police to save his wife. Within minutes, backup arrived. Blood stains were all through the house, and a puddle of congealed blood in the bedroom “looked basically like jelly,” according to one officer, also an EMT.

Two cops found Sue on the floor of the office, her back against the desk, covered in blood. On first glance, they thought she was dead, but then they saw blood oozing from a gash on her neck to the rhythm of a heartbeat. The cop with EMT training packed the wound, but it kept bleeding through the fabric bandages. To stop the flow, he had to stick his finger in the wound up to the first knuckle. Sue kept asking him to save her cats, indoor cats that wouldn’t survive if they got loose.

Out on the deck, another officer pressed a dishtowel to Leo’s neck, trying in vain to stop the bleeding. “I know who did this,” Leo said.

***

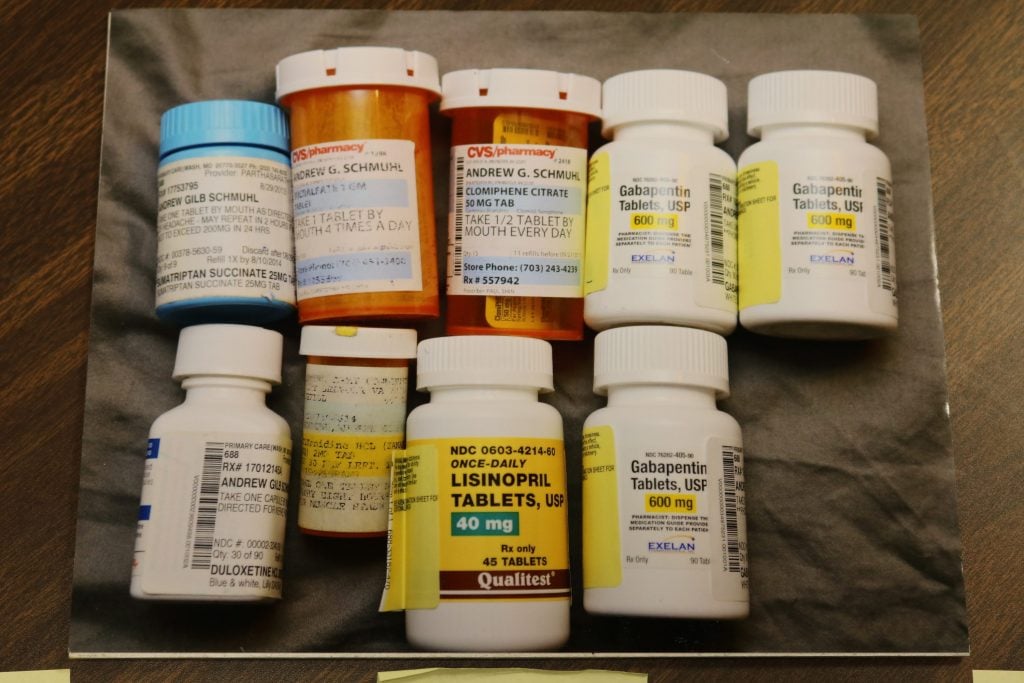

Six months before the attack, 31-year-old Andrew Schmuhl lay in bed each morning, cramps spreading across his back. The pain from his spinal injury was getting worse, despite the Fentanyl and other drugs his doctors had prescribed, so many that a friend called him “a human pincushion.”

Before the injury, Schmuhl had been an active person, a runner. He loved woodworking and had worked on houses since he was a kid in Fond du Lac, Wisconsin. He and his mechanical-engineer father used to build garages together. Andrew played football and chess and had “lots of friends, close friends,” recalls his mother, Mary Schmuhl. “He went to prom. Homecoming.”

Andrew wanted to be a lawyer. After graduating from Marquette University, he enlisted in the Army and enrolled at Valparaiso Law School in Indiana. That’s where he met Alecia Pehr. She was a smart, pretty student from the Chicago suburbs who played the violin and was editor of the law school’s student newspaper. Alecia, one former classmate remembers, was “fairly normal. Liked to have fun. She would go to bars, liked to have drinks with us.” Another recalls her as “feisty.” According to the classmate, she ran an anonymous blog called Silly Little Law Student and sometimes used it to vent about the pressures of school and social life, once posting a picture of a young woman she didn’t like and writing “The Succubus” next to her face. Andrew was more of a mystery. “People thought he was a little bit odd,” says the first classmate. “He just didn’t have the strongest social skills.” When word got out that Andrew and Alecia were dating, everyone was surprised.

During school, Andrew was briefly married to a woman from Wisconsin. After divorcing, he married Alecia, who took his name. The couple graduated in 2009 and moved to Washington. Alecia found a job as an immigration attorney with a small Fairfax firm, and Andrew became an Army lawyer, an active-duty officer with the Judge Advocate General’s Corps. One of his responsibilities was to help soldiers process their medical claims. His parents remember how he’d let the servicemembers’ kids take candy from a bowl on his desk. There were toys to play with, too. It didn’t look like a military office, his father, Don Schmuhl, says: “It looked happy.”

Another of Andrew’s roles involved prosecuting military members, particularly for crimes that involved electronic information. He gave government lawyers advice on searching hard drives and e-mail, and later he would claim on his LinkedIn page that he “authorized the search of email accounts” for Chelsea Manning, the Army specialist now in prison for providing classified information to WikiLeaks.

Andrew’s Army career, however, was cut short. One day during physical training, he slipped on a patch of ice, fell, and injured his spine. In 2012, he took a medical discharge. By the summer of 2014, Andrew was confined most days to the couple’s home in Springfield. He collected disability, about $1,100 a month, but was otherwise supported by Alecia, then an intellectual-property lawyer at Bean Kinney.

The pain from his spinal injury was getting worse, despite the Fentanyl and other drugs his doctors had prescribed, so many that a friend called him ‘a human pincushion.’

Each morning after she left, Andrew soaked in the bathtub for two or three hours. If the pain subsided, he might do a couple of chores. Often he broke out in drenching sweats, as if he’d just run a marathon. These were a symptom of opioid dependency. Like more than 2 million other Americans, Andrew Schmuhl had become addicted to prescription pain medication.

The most powerful drug in his regimen was Fentanyl, a synthetic opiate 50 to 100 times more powerful than morphine and one at the heart of a growing epidemic. (The DEA calls it “much more potent than heroin.”) Andrew’s doctors at the Department of Veterans Affairs had raised his Fentanyl dose twice over the previous two years. He wore a patch on his arm that delivered the drug directly through the skin. He also swallowed a second opioid in pill form, Dilaudid, every four to six hours.

That wasn’t all. Not even close. He wore a Clonidine patch, a blood-pressure medication. He was on Toradol, a daily injection to reduce pain and inflammation—Alecia had to stick the syringe into his legs because Andrew hated needles and couldn’t do it himself. He took Gabapentin, an antiseizure drug also effective with some kinds of pain, three times a day. Lisinopril for high blood pressure. Cymbalta, an antidepressant. He took Sumatriptan for migraine headaches; Tizanidine, a muscle relaxer; Sucralfate, for gastrointestinal issues. He also used over-the-counter remedies: Pepto-Bismol, Ex-Lax, NyQuil, Benadryl, and medicated patches that Alecia placed directly on his back wherever it hurt.

While Andrew struggled with his meds, Alecia was falling behind at work. She’d been at Bean Kinney about a year, hired by Leo Fisher. A pillar of the firm for nearly 25 years, Leo had helped build its reputation while serving as a widely liked mentor to young attorneys. One former partner, Heidi Meinzer, remembers that shortly after she was hired, Leo confessed that during her salary negotiation, the firm had lowballed her. “He bumped my salary and made it retroactive,” Meinzer says. (Fisher declined to speak for this story. All of his and his wife’s quotes are from testimony.)

When Alecia began missing meetings and deadlines, Leo’s partners complained about her performance. Then in June 2014, Leo learned that Alecia had listed her husband as an employee of the firm on a mortgage application and had impersonated its human-resources director in a phone call with the bank. According to the couple’s phone records, Andrew had urged her to do it. “Just pretend to be someone,” he’d texted Alecia. “Hell, make up an accent.”

Leo told Alecia her behavior might constitute fraud. He sent her home without deciding whether she’d be fired: “When you see people with promise, you want to give them a chance.” But the next morning, when Leo arrived at work, Andrew Schmuhl was there, uninvited. Surprised, Leo pulled the Schmuhls into his office. Andrew started to get angry, raising his voice, cheeks reddening as he insisted the couple wasn’t trying to commit mortgage fraud. Leo said he needed to talk to Alecia, but Andrew wouldn’t let him get a word in. Finally Alecia turned to her husband and said, “Andrew, leave now, because I want to save my job.” He got up and walked out.

Even then, Bean Kinney didn’t fire Alecia, but as summer turned to fall and her performance continued to lag, the decision was made to let her go. On October 27, 2014, Leo handed her a letter offering a severance payment. He said he knew Alecia would turn out to be a great lawyer, somewhere else.

“Huh?” Andrew replied after she texted him the bad news.

Andrew’s misery had only increased in the months since his confrontation with Leo. He had been rushed to the ER because of a kidney stone. Surgery to remove it gave him incontinence. Then an endocrinologist had diagnosed him with low testosterone and prescribed Clomid, a hormone modulator. Andrew noticed an immediate change in how he felt: “a weird disconnected fuzzy feeling,” he would say later, “weirdness on top of weirdness.”

In addition to these complications, he had just been served with a court order faulting him for being past due on credit-card and student-loan debts that were part of his divorce case.

Andrew now texted Alecia: “employment attorney stat.”

Alecia wrote back: “I know Honey.”

A gender-discrimination suit against the firm could be lucrative, he replied—Alecia would make more money from a lawsuit than from severance. The legal discovery process would let her dig into Bean Kinney’s finances and its e-mails, “which are probably a gold mine,” as Andrew put it. He wrote, “I want your name on their goddamn door.” Referring to Leo, Andrew went on: “Don’t count on that scum. He is a worthless piece of sniveling shit.” Alecia texted, “Yes he is.”

***

“S-C-H-M-U-H-L,” Leo Fisher said to police on November 9, 2014, spelling out his attacker’s name as he bled on his front deck.

Until that moment, Leo had kept the intruder’s identity to himself, not wanting Andrew to realize he recognized him.

A message went out for police to watch for the Schmuhls’ Honda SUV. Ten minutes later, two K-9 units spotted the vehicle on the Beltway, but when they tried to pull it over, the Honda sped away. One of the K-9 cops peered in and saw a woman driving and a man in the passenger’s seat frantically removing his clothes. They seemed to be having an argument.

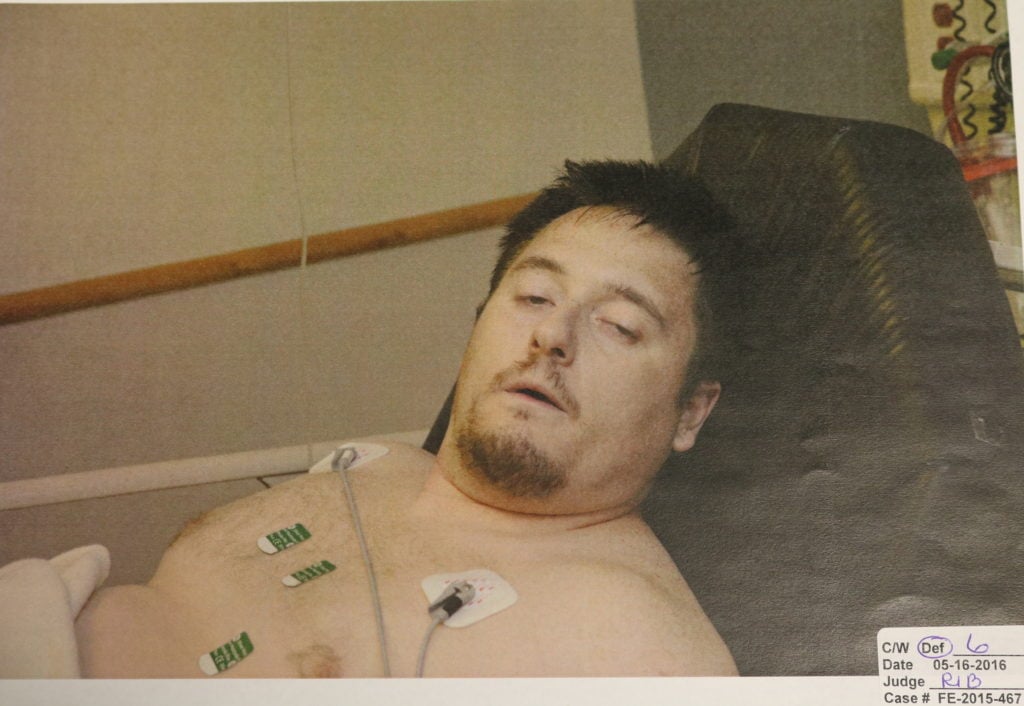

After several miles, the car finally stopped at a strip mall off the highway. Suddenly, and without being told to, the man got out of the car—naked except for an adult diaper. It was Andrew Schmuhl.

One of the cops ordered him to the ground at gunpoint; the other deployed his dog and said that if Andrew didn’t comply, he’d be bitten. Andrew lay down and was handcuffed, and the police began asking questions. At first, he seemed lucid. A few minutes later, though, an officer “noticed that there was a pretty distinct change” in Andrew’s level of consciousness, he would testify later. Andrew’s eyes were rolling around, and he appeared almost to be passing out. He started speaking in German.

The officer asked if he’d taken drugs, and Andrew said yes: Fentanyl, Dilaudid, and some others. By the time an EMS lieutenant arrived in an ambulance, Andrew looked pale and had a slow heart rate.

“Okay, so why are you in handcuffs?” the lieutenant asked.

Andrew replied, “I can’t talk about it.”

Medics found a Fentanyl patch on his left arm and ripped it off. Unknown to them, he was wearing another patch under his diaper.

Alecia Schmuhl—who had been driving the Honda—was loaded inside a different cruiser. She was calm (and fully clothed), though a video camera in the car recorded her saying to herself, “Oh, God—his computer,” as if worried about what police might find on Andrew’s laptop.

Inside the Honda, police found all manner of paraphernalia tied to the torture: a Taser, the parts of a disassembled Cobra .380, the knife Andrew had used to stab Sue and Leo, credit cards, a pile of bloody clothes doused in ammonia, Tizanidine pills, a novelty police badge, and two handwritten notes. One note, later determined to be in Alecia’s handwriting, contained directions to an address next to Sue and Leo’s. The second note, in Andrew’s handwriting, looked like a shopping list. It read:

— handcuffs

— 2 bottles nyquil

— 2 packs benadryl

— 1 adult diaper

— 2 adult sleeping masks

EMTs sped Andrew to Inova Fairfax Hospital in Arlington, where he was given an injection of Narcan, a drug used to reverse the effects of opioids. Within minutes, his condition improved. Hospital staff also discovered the Fentanyl patch under the diaper and removed it. Meanwhile, Inova doctors and nurses were also treating the victims, Leo Fisher and Sue Duncan, preparing them for emergency surgery to save their lives. The last thing Leo remembered before going under anesthesia was someone cutting off his pants. Someone stapled Sue’s head wound shut. Later she would remember the sound of the staples—“bam, bam, bam, bam.”

***

Andrew Schmuhl’s parents didn’t hear about the attack until November 11, two days later. They got a call that night telling them that Andrew was in jail. A grand jury would later indict Andrew on seven charges of abduction, aggravated malicious wounding, use of a firearm, and burglary, spelling out a potential minimum prison term of 108 years. But as they drove east through the night, 13 or 14 hours, to see their son, they knew only that he had been implicated in a violent crime and that it didn’t make any sense. When they got to see him in jail, “all he said was he didn’t remember anything,” Mary Schmuhl recalls. “And it’s been kind of fuzzy ever since.”

This eventually became the central question at Andrew Schmuhl’s trial: Was he in his right mind during the attack? Was the “interrogation” and torture of Leo Fisher and Sue Duncan the cold-blooded act of a monster, or was he a basically decent person turned into a zombie by prescription medications and their toxic interactions?

Alecia, who faced similar charges, was originally supposed to stand trial with her husband, but Judge Randy Bellows severed the cases after Alecia’s lawyers alleged that Andrew had abused and controlled her for years. “There has never been any inclination or tendency toward violence in Ms. Schmuhl,” her lawyer said in court. The attorneys have stated that Alecia waited outside the Fisher and Duncan home but didn’t know what was happening inside. Alecia’s claim of spousal abuse is “categorically false,” Bradley Haywood, Andrew’s lead attorney, told me.

From the beginning of Andrew’s trial this past spring, both sides mostly agreed on the facts: Andrew hurt Leo and Sue. The mystery, and the battle that played out in court, was all about the why. Prosecutors Casey Lingan and Kathryn Pavluchuk portrayed the defendant as a “murderer at heart,” a liar, and a con man: “It’s about revenge,” Lingan said in his opening statement. “It’s about greed. It’s about anger. It’s about torture.” Andrew’s court-appointed lawyers argued that he was a man with a good heart poisoned by the very medicine that was supposed to help him, a suffering veteran who had been failed by his VA doctors and betrayed by a domineering, calculating wife. “Something was horribly wrong with Andrew Schmuhl’s mental state that night,” defense attorney Andrew Elders told the jury. “The cause of that problem was his medication.”

The most powerful drug in his regimen was Fentanyl, a synthetic opiate 50 to 100 times more powerful than morphine and one at the heart of a growing epidemic.

This type of defense is known as “involuntary intoxication.” As with insanity, it requires proving that a defendant’s mental state was altered to the point that he didn’t understand the consequences of his actions. With insanity, the cause of the mental state is disease. With involuntary intoxication, the cause is a drug that is ingested “without his willing or knowing use,” according to Virginia precedent. Maybe a defendant was at a bar and someone put PCP in his drink, or maybe a doctor prescribed the wrong pills.

Involuntary-intoxication defenses are rare and hard to win. Bellows, the Fairfax County judge in this case, had never presided over a trial involving one. “Absolutely a long shot,” according to Haywood, Andrew’s lawyer, because from a juror’s perspective, “you know who he is, you know what he did, and you’re being asked to let him go.”

Haywood and his team planned to make their case with the help of Dr. Eileen Ryan, a University of Virginia psychiatrist who had experience treating patients with chronic pain. They planned to call her as an expert witness. Before the trial, Ryan had interviewed Andrew at length and studied his medical records, and she believed that on the night of the crime he was suffering from “medication-induced delirium.” Delirium is a recognized medical condition, an acute state of mental disturbance that is temporary and reversible. People experiencing it can be agitated, apathetic, or both. They may appear to be in control of their actions but are sometimes unable to remember them later. There’s always a specific trigger for the delirious state, a medical cause such as alcohol withdrawal, a chronic illness like dementia, or a drug overdose. Medical literature contains reports of Fentanyl patients experiencing delirium.

In Ryan’s opinion—she was prepared to say this on the stand—Andrew fit this pattern. He had never been diagnosed with any kind of mental illness; his mental state became altered for a brief period, and then he returned to normal. Ryan thought the trigger for Andrew’s state of delirium was most likely a toxic overdose of Fentanyl. Her opinion was bolstered by the fact that when Andrew was injected with Narcan, a drug whose only function is to reverse an opioid overdose, it seemed to work.

For strategic reasons, Andrew’s lawyers waited until the trial to reveal the main thrust of their argument, not wanting to show their cards to the prosecution until the last moment. But the tactic backfired. The state complained that the defense was sidestepping procedural rules that would have let the state’s medical expert evaluate Andrew. Judge Bellows agreed. According to his ruling, which relied on a 1985 legal precedent, the defense was free to claim involuntary intoxication and Ryan could testify about the effects of drugs and toxic drug interactions, but she couldn’t offer a medical diagnosis of Andrew. She couldn’t explain how delirium might have accounted for his behavior on that awful night. She couldn’t even use the word “delirium.”

As a result, Andrew’s trial became less about modern medical reality, the potencies of Fentanyl and Dilaudid and Clonidine and Clomid and Toradol and Tizanidine and Gabapentin. It became instead a traditional morality play, a turn that favored the prosecutors, who used surveillance footage, phone records, recovered evidence, and the recollections of Sue and Leo to tell a story of greed and revenge.

***

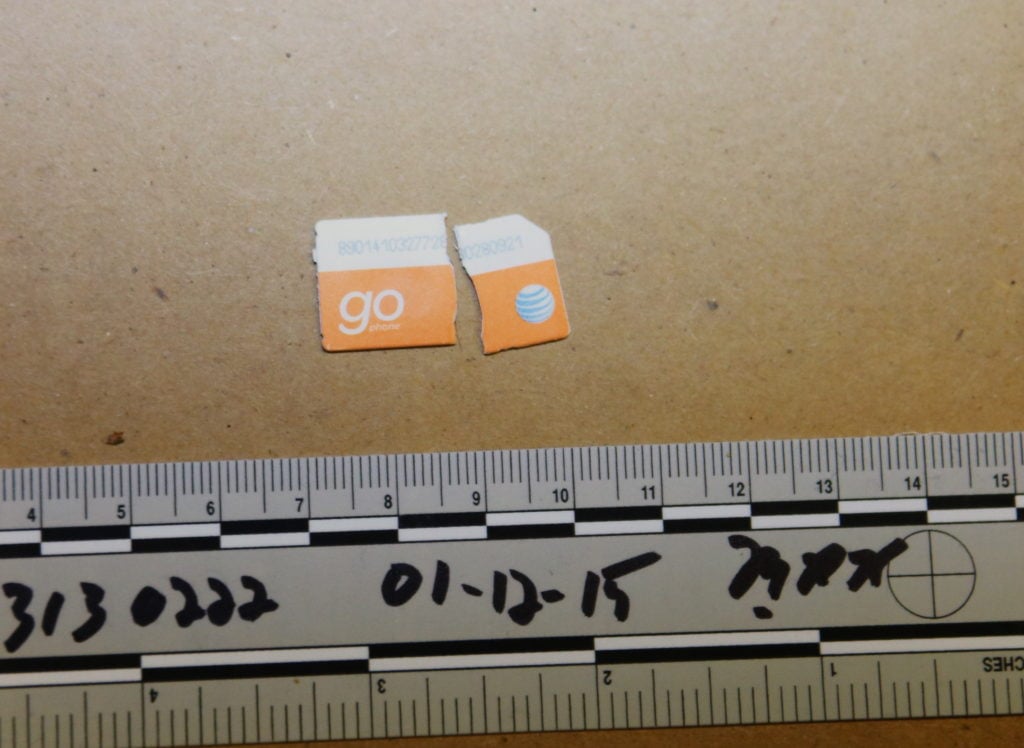

Eleven days after the sole breadwinner in the Schmuhl house lost her job and two days before the home invasion at Sue and Leo’s, a security camera at Nova Armament in Herndon snapped footage of Alecia Schmuhl buying a Taser. The same day, she bought three items later found on the shopping list—NyQuil, Benadryl, and adult diapers. Andrew, meanwhile, had purchased two prepaid GoPhones, evidence suggested. One phone was given the name “Panama,” the other “OP.” In military argot, OP stands for Observation Post.

Prosecutors pointed to all this as proof that Andrew and Alecia had conspired to plan the attack. Afterward, according to the state, they tried to erase their physical and digital trail. A gasoline stain on Leo and Sue’s rug suggested an apparent botched attempt to burn down the house, Andrew’s bloody clothes were found doused in ammonia, the Cobra .380 was disassembled, and the SIM card for one of the prepaid “burner” phones was snapped in half. (Police taped it back together and got it to work.)

As for the argument that Andrew was mentally impaired during the attack, the state used testimony from the victims themselves to show how his behavior during the torture session contradicted his confused state afterward. “In the police car he looks subdued,” Sue Duncan said. “He hesitates before answering even the most basic questions. . . . He’s acting much slower. In the house he was completely different. He was authoritative, he was in control.” At times, she broke down crying.

The defense countered by trying to shift blame to Alecia—in their rendering, “an aggressive person who sought out confrontation,” a highly intelligent schemer who manipulated her ill husband to get what she wanted. Andrew’s mother, Mary Schmuhl, testified that in the past she had seen Alecia hit and kick her son: “She would haul off and just hit him in the arm as hard as she could.” (Alecia pleaded the Fifth during the trial. Her attorneys declined to comment.)

Alecia, the lawyers pointed out, was the one who bought the Taser. She was the one who knew about Bean Kinney’s computer network that Andrew tried to invade. Many of the questions he asked Leo and Sue were full of details about life at the firm that Andrew couldn’t have known. And all the while, Alecia was waiting outside with the getaway car, which she drove. The home invasion, the defense concluded, was clearly “Alecia’s operation.” Andrew was just the foot soldier, too whacked out on his meds to execute the plan correctly.

Although the defense couldn’t mention delirium by name, they were able to talk around it when Ryan took the stand. Instead of delirium, she spoke of an “acute confusional state.” Instead of saying Andrew was delusional or psychotic, she said he wasn’t connected to reality. Andrew’s attorneys highlighted that disconnection by emphasizing the bizarre details of the attack. If the plan was to murder Leo and Sue, why would Andrew pretend to be a “Virginia SEC” agent? If the plan was to steal information for Alecia’s employment-discrimination lawsuit, why didn’t he download a single e-mail or document from Leo’s computer? If Andrew was trying to burn down the house, why didn’t he light the gasoline? Why was he wearing an adult diaper if he was constipated more often than he was incontinent? (The prosecution argued that he wore it so he wouldn’t have to take bathroom breaks while torturing the victims.) If the attack was about revenge, why didn’t he tell the couple who he really was, to take pleasure in their recognition? Why wear a weird disguise? Andrew’s hat wasn’t just an Indiana Jones–style hat, defense attorney Elders pointed out. It had been purchased from the actual Indiana Jones Collection. The badge he flashed at Sue wasn’t real, or even a convincing fake. It was the kind women buy for bachelorette parties, with a picture of a penis on it and the words pecker inspector, department of erections.

As the trial wore into its third and fourth weeks, the boxes of exhibits piling up on pushcarts toward the ceiling, Haywood kept trying to convince Judge Bellows to reverse himself on Ryan’s testimony, scrambling for new arguments and angles and reading from stacks of legal precedents and medical-journal articles. The judge always listened patiently and always restated his original ruling.

Then toward the end, something surprising happened: Haywood called Andrew Schmuhl to the stand.

Defendants don’t usually testify, because it opens them to cross-examination, but Andrew’s team felt it was worth the risk: The jury needed to know all the drugs he had been taking, and there were holes in his medical records. Word got around the courthouse, and spectators poured into the gallery. Andrew made his way to the witness box, wearing a navy suit and leaning on a cane. Haywood asked him to list the drugs. Then Haywood inquired about the second Fentanyl patch found on Andrew’s body that night, the one under the diaper. The defendant said he didn’t know how the patch had gotten there and that Alecia was the only one who ever put patches on his back—implying his wife had drugged him.

Haywood also asked Andrew what he remembered about November 9. Andrew said his last memory from that day was from the afternoon or early evening, when he and Alecia went on a drive through the Shenandoah Valley. Next thing he knew, he was in the hospital. He didn’t remember going to Leo and Sue’s or anything that happened inside their home.

Schmuhl’s claims of forgetfulness fit the overall defense strategy of blaming the drugs, but the testimony also created an opening for prosecutor Casey Lingan. When Andrew said he didn’t recall buying or using the burner phones, for instance, Lingan shot back that at 12:01 pm on November 7, the phones were communicating with each other next to the gun store where Alecia had bought the Taser. “And you don’t remember that, either, do you?” Lingan said.

“I don’t remember using those prepaid GoPhones,” Andrew said.

“But you could have?”

The defendant paused.

“Tricky, isn’t it?” Lingan said, insinuating Andrew was lying. A murmur rippled through the gallery. “Either you do remember or you don’t remember.”

“I can’t specify that I don’t remember to a negative,” Andrew said.

The judge said: What? What does that mean?

Andrew replied: “I can’t specifically say that I don’t remember something that I don’t remember.”

It went on like this. In response to questions from Lingan, Andrew said he didn’t recall ever having the Taser in his hand. He didn’t remember binding Leo and Sue’s hands and feet, or forcing them into their bedroom, or searching for information on Leo’s computer. He didn’t remember cutting Leo’s throat or shooting Sue or stabbing her repeatedly in the back.

“So let me ask you this,” Lingan said, then walked the defendant through actions he must have taken immediately after the attack, in a seemingly deliberate attempt to cover his tracks. At what point did Andrew pick up the spent shell casing from the gun he fired at Sue? When did he retrieve his jacket and hat that he’d removed inside the home earlier in the night? When did he decide to pour ammonia on his bloody clothes? When did he decide to disassemble the gun?

Schmuhl leaned into the microphone and gave the same answer, again and again, in a flat voice: “I don’t know.”

***

The jury deliberated for almost a day before reaching a verdict. People filed into the courtroom to hear it, packing the benches. Leo sat with relatives. On count one, Judge Bellows’s clerk began to read aloud, the jury finds the defendant guilty. Leo smiled and nodded. Andrew Schmuhl stared at the wall in front of him as he had done throughout the trial. The clerk said the word “guilty” six more times: guilty on all counts. Don Schmuhl put his arm around Mary and squeezed.

Later, I interviewed juror Amber Tussing, who is in her late thirties and works for the Defense Department. She says the jury spent all morning discussing whether Andrew had been involuntarily intoxicated and reached a unanimous decision after lunch: No. “There just wasn’t any proof from the defense that he was uncontrollably under the influence of anything for the three hours that he was in the house,” Tussing says. Jurors found Ryan’s testimony muddled. Listening to her talk about drug effects and interactions “was like listening to a commercial for a new type of medication,” Tussing says. “If you take this for high blood pressure, you’re at risk for this, you’re at risk for that.” Andrew’s testimony didn’t sway the jurors one way or the other, though they were troubled by his apparent lack of remorse. As Tussing puts it, “He was visually, physically, about as cold and if-looks-could-kill as you could imagine.”

The jury ultimately handed down a sentence of two life terms in prison plus 98 years. Unless the case is reversed on appeal, Andrew will likely be in prison the rest of his life.

A short time after Andrew learned his fate and was taken back to jail, Don and Mary spoke to him on the phone. “I think he’s just as much in shock as we are,” Mary told me in a call from Fond du Lac. She said it’s hard not to cry when they look at pictures of their son or walk into his old room. “We’re still looking for answers. We may or may not ever get them. Somebody has some answers out there. It’s just not us.”

The trial of Alecia Schmuhl, originally scheduled for September 19, could have shed more light on the crime. But that day in court, she pleaded guilty to all five charges. She faces between 10 and 45 years in prison, according to her plea agreement, and will be sentenced in January.

For Leo Fisher and Sue Duncan, the plea means they won’t have to relive their trauma during another trial. The attack left them with lasting injuries, some permanent. Sue experienced concussion-like symptoms in the aftermath and still has ringing in her ears. Her back aches all the time from the scars of the stab wounds, which formed keloids, “like this raised, hard red ridge,” she says. Leo has trouble chewing and swallowing food: When Andrew cut his throat, it severed the nerves on one side of his face, making it difficult to control his tongue. When he gets tired, he slurs his words. It’s a permanent injury that has affected his livelihood, his ability as a lawyer to speak clearly.

The attack also changed Leo in less tangible ways. He always considered himself a calm and open-hearted person, but now he feels rage, and it’s hard to press it down. It’s hard to watch his wife suffer, too—Sue, the one who saved them both. They would have died if she hadn’t triggered the security alarm and dragged her bleeding body to the phone. She isn’t interested in socializing anymore. She has nightmares. She wakes up thinking people are coming in the night to kill her. There are moments when he can hardly bear it. At trial, on the stand, Leo Fisher, a quiet man, tried to describe the feeling. “I just want to eject myself from where I am and scream at the top of my voice,” he said. “I’ve never been a person who hated before, and I hate now.”

This article appears in our October 2016 issue of Washingtonian.

Contributing editor Jason Fagone (@jfagone on Twitter) also writes for Huffington Post Highline and is an author at HarperCollins. Greta Weber contributed reporting for this story. It was reported through court testimony, court records, and interviews.