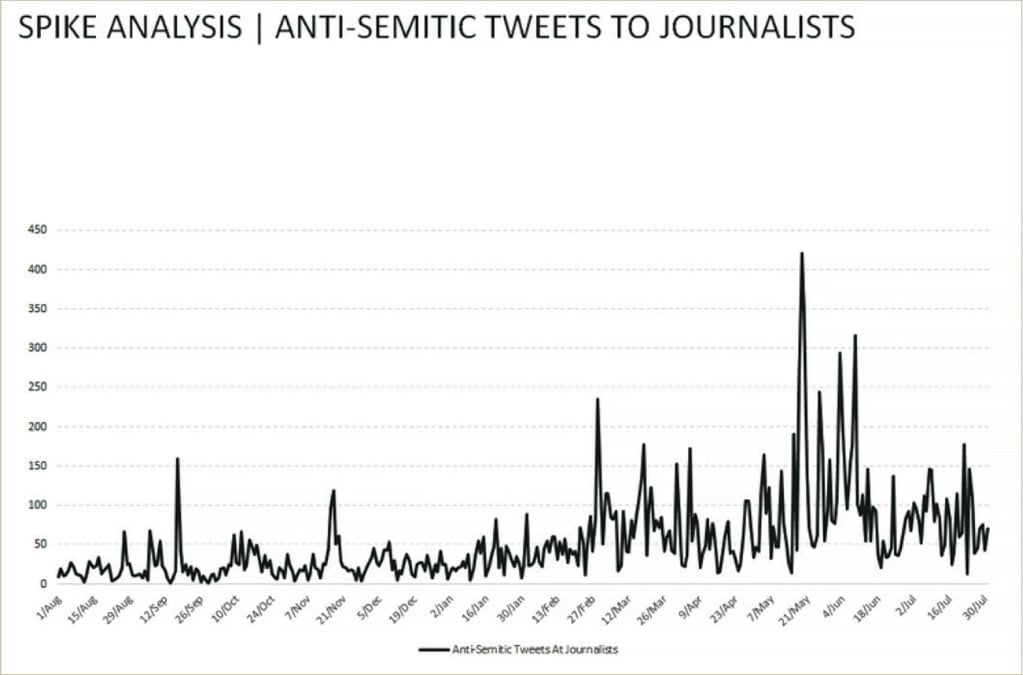

Just ten journalists were the targets of 83 percent of anti-Semitic tweets over a one-year period reviewed by the Anti-Defamation League, according to a report published Wednesday by the civil-rights organization. The ADL studied Twitter messages sent between August 2015 and July 2016 and found that the offending messages were fueled largely by rhetoric in the presidential election and hate groups that have encouraged anti-Semitic speech.

The rise in social-media accounts explicitly targeting Jewish journalists is not just part of an unprecedented surge inanti-Semitic speech in American life, says ADL National Director Jonathan Greenblatt, it represents an assault on free speech.

“These are coordinated and deliberate and direct at particular individuals,” Greenblatt tells Washingtonian. “Prominent journalists, conservative and liberal, Republican-leaning and Democrat-leaning, and those without any leaning at all. Because it’s an attempt to silence speech and it’s an attempt to marginalize Jewish voices, it’s an attempt to silence the media, which is also really worrisome.”

The spike in anti-Semitic tweets emanates largely from accounts that identify themselves as supporters of Republican nominee Donald Trump, whose nationalist platform has been embraced by members of the so-called “alt-right,” a emerging movement with members who have espouse white-supremacist ideology. Many of the journalists on the receiving end of the messages analyzed by the ADL have written articles critical of Trump’s candidacy or personal life.

While the Anti-Defamation League takes no sides in the election, its report calls out Trump, whose Twitter account has republished messages first posted by white-supremacist users and who regularly trashes media during campaign events, for fostering a hostile environment. “There is evidence that Mr. Trump himself may have contributed to an environment in which reporters were targeted,” the report reads. During his campaign, Trump has referred to reporters covering his campaign as “absolute scum,” “sleazes,” and “lying, disgusting people.”

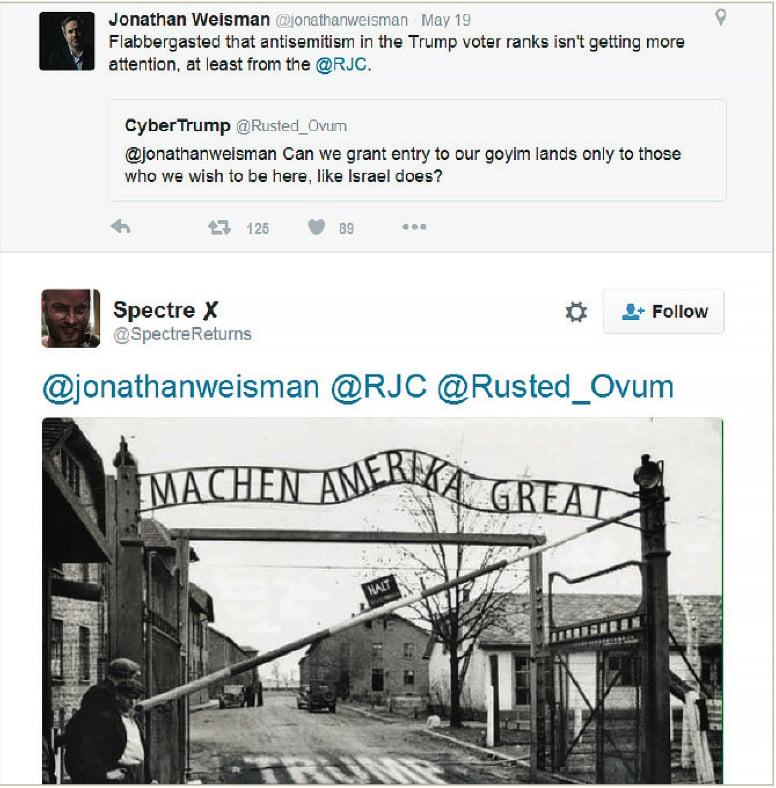

Some of Trump’s supporters have taken his campaign as agency to go much further. As the ADL’s report recounts, writer Julia Ioffe was besieged with a “firestorm of virulently anti-Semitic” tweets that used anti-Jewish slurs and photos of Nazi concentration camps in response to a profile of Melania Trump she wrote for GQ in May. That same month, Jonathan Weisman, a deputy editor in the New York Times‘s DC bureau, came under attack for tweeting about casino executive Sheldon Adelson‘s support of Trump, receiving tweets containing images of himself manipulated to feature him wearing Juden stars as the Nazi regime forced German Jews to wear in the 1930s.

The ADL’s study was prompted in part by some journalists reaching out to Greenblatt directly, clearly distressed by the abuse they’d received. “Several said to me they were finding themselves self-censoring or reconsidering writing stories out of fear of the retribution that would result,” he says. “I had others tell me they were thinking of leaving journalism because the exposure was too high and the level of attacks were too personal.”

Many other journalists—Jewish or not—have experienced similar reactions on social media after posting items that could be seen as critical of Trump or the alt-right movement, the ADL reports. In June, Twitter user @FoundersRace sent me a tweet featuring a quote from Nazi propaganda chief Joseph Goebbels attributed to Taylor Swift, a riff on a meme that attempts to invoke the pop singer as an “Aryan goddess.”

“What’s so interesting about Taylor Swift and even Pepe the Frog”—a cartoon amphibian that the ADL now lists as a hate symbol after its appropriation by the alt-right—”is how they’ll try to exploit images that are innocuous,” Greenblatt says.

In its research, the ADL first pulled 2.6 million tweets—garnering an estimated 10 billion impressions—using keywords associated with anti-Semitic language. Ten billion impressions is roughly the social-media equivalent of a $20 million advertising campaign during the Super Bowl; the ADL calls it “a juggernaut of bigotry we believe reinforces and normalizes anti-Semitic language and tropes on a massive scale.” The organization says it did not use search terms relating to the election. From there, it compared those results with tweets sent to a list of about 50,000 journalists. After a manual review, it focused on 19,253 explicitly anti-Semitic messages tagging about 800 reporters and editors. Some of the most common terms in that set included “kike,” “Israel,” “Zionist,” “white,” and “Trump.”

Those 19,253 tweets collected about 45 million impressions. Of those, more than four-fifths went to just ten journalists, including Weisman. The top target by a wide margin, though, was conservative writer Ben Shapiro, who was tagged in more than 7,400 of the tweets—about 38 percent of the total—after leaving the Trump-supporting website Breitbart in March after Trump’s then-campaign manager, Corey Lewandowski, was accused of assaulting Shapiro’s colleague Michelle Fields during an event in Florida. (Fields also left Breitbart after the site sided with Lewandowski and now works for the Huffington Post; Breitbart chairman Steve Bannon is currently serving as chief executive of Trump’s campaign, while Lewandowski is a CNN commentator who still travels with Trump.)

Last July, after Trump retweeted a meme featuring an graphic describing Democratic nominee Hillary Clinton as the “most corrupt candidate ever” with those words printed on a Jewish Star of David over a photo of US currency, Greenblatt told Washingtonian that Trump is “absolutely not” an anti-Semite, but that the Republican nominee needed to “take a stand” against the anti-Jewish speech some of his supporters were engaging in at the time. In the months since, it appears Trump has failed to do so.

“Number one, he’s not responsible for the anti-Semitic harassment. I can’t attribute causation,” Greenblatt says. “What I think is unambiguous, what is empirical is that a majority of the harassment originates from accounts that identify themselves as Trump supporters. And I say that because the words most frequently used in their bios are ‘Trump’ and ‘white’ and ‘nationalist.'”

Greenblatt admonished Trump again on Twitter last week after the GOP nominee accused Clinton of meeting “in secret with international banks to plot the destruction of U.S. sovereignty in order to enrich these global financial powers, her special interest friends and her donors,” a line that some felt hewed uncomfortably close to the 1920s anti-Semitic tract Protocols of the Elders of Zion.

For Twitter’s part, the company and other Silicon Valley firms are part of the ADL’s cyber-hate working group and has shut down about 21 percent of the accounts that sent the abusive, anti-Semitic tweets identified by the organization. But that leaves 79 percent of the offending Twitter users in operation. In a secondary report due out November 19, the ADL plans to issue recommendations to the social-media industry about weeding out hate speech. “I think there’s more they can do,” Greenblatt says.

Anti-Semitic speech has been an element of digital communications since the internet’s earliest days, Greenblatt says, pointing to late-1980s bulletin boards. But for the most part, it has been confined to the fringes. Social media—and a presidential election—has brought it into broader view, the ADL report concludes. Even if Trump and his supporters are dealt a defeat November 8, Greenblatt says the last year has pushed anti-Semitic language closer to the mainstream.

“The bottom line is you’re seeing a mainstreaming of anti-Semitism,” Greenblatt says. “You’re seeing the climate acclimate toward it in ways that make us all very uncomfortable. Anti-Semitism is historically the first sign of the infection, and the infection tends to spread. If we don’t cut out this cancer, the disease will condemn all of us, so we’ve got to step up.”

Read the ADL’s report below:

Adl Taskforce Report Final by Benjamin Freed on Scribd