On September 18, 1884, more than 100 journalists, farmers, and politicians gathered at an old farmhouse near a railroad station in Maryland to hear a woman speak. They sat at picnic tables set with lemonade and cake, listening intently as Belva Lockwood laid out the radical platform of her candidacy for president of the United States.

In her first speech of the campaign, Lockwood affirmed her legal right to run for the nation’s highest office despite the fact that her gender could not yet vote. She argued that nothing in the Constitution barred her from running. “I cannot vote, but I can be voted for,” she said.

More than 130 years later, not far from where Lockwood gave that first speech, the lady candidate has “risen from her grave” in the Congressional Cemetery. She’s come back to witness the candidacy of the first-ever woman nominated by a major party for the United States presidency. Before she died, Lockwood said that if a woman ever became president, it would be “entirely on her own merits” and not because of her gender.

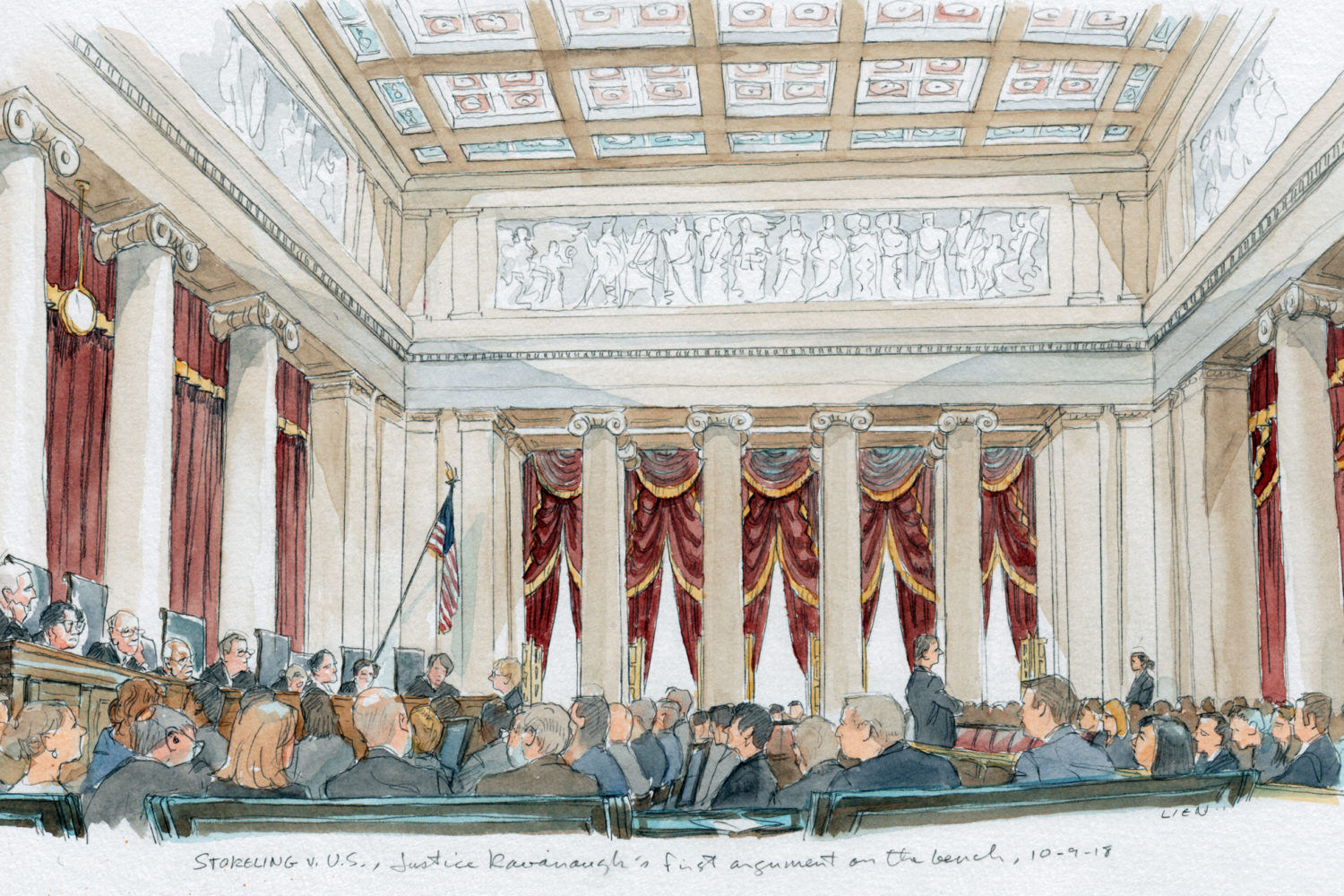

You can meet Belva Lockwood, as well as some of her cemetery neighbors, at the Congressional Cemetery this weekend and next for its second-annual Soul Strolls. Lockwood, played by local actress Sally Cusenza, will be standing near her grave talking about her historic firsts: She was the first woman to run a full presidential campaign (Victoria Woodhull or “Mrs. Satan,” as she was called, ran a partial campaign in 1872), the first woman to be admitted to the Bar of the Supreme Court, and the first woman to participate in oral argument at the Supreme Court.

She wouldn’t live to see the enfranchisement of women, but she undoubtedly laid the foundation for it. “We shall never have equal rights until we take them, not respect until we command it,” she said.

Lockwood, then 36, moved to Washington from rural New York in 1866. Despite prominent newspaperman Horace Greeley’s observation that it was a city where “the rents are high, the food is bad, the dust is disgusting, the mud is deep, and the morals are deplorable,” she saw in Washington an opportunity to throw off what she called “a woman’s shackles” by pursuing education and politics.

Before making the leap, however, her life in New York was on a very different path. At 18, Belva got married and started work as a teacher, for which she was paid less than half of the salary made by her male colleague, something she called “odious, an indignity not to be tamely borne.”

At the same time, just 90 miles east from where Belva and her husband lived, women had started publicly voicing their frustrations. In 1848, suffragists held the very first women’s rights convention in Seneca Falls, New York. Reading about Elizabeth Cady Stanton’s radical keynote address in the papers, Belva felt a kinship to the new movement. Her frustrations about the mundanity of womanhood could come out of the shadows.

At 22, when her husband died in a mill accident, Lockwood was free to leave her small hometown. She would write in an autobiographical article that she chose Washington “for no other purpose than to see what was being done at this great political centre—this seething pot—to learn something of the practical workings of the machinery of government, and to see what the great men and women of the country felt and thought.”

Inspired by heated political discussions over African-American and female voting rights at the time, Lockwood helped found the Universal Franchise Association in 1867. The goal of the group was to publicize the demands of women’s rights and recruit more supporters. This wasn’t an easy task: At meetings, bystanders would ridicule Belva and her colleagues and literally throw vegetables at them. When she wasn’t at UFA meetings, Lockwood lobbied Congress for universal suffrage alongside Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony.

In 1870, Lockwood applied to the DC’s Columbian Law School. She was denied entry by the all-male faculty, who claimed her presence “would likely distract the attention of the young men.” Unfazed, she then applied to the new National University Law School (which later merged with George Washington University) and was eventually admitted. Although she completed the necessary course load in 1873, the school refused to grant her a diploma. Without a diploma, she was not eligible to become a member of the DC Bar.

A year later, Lockwood wrote a letter to President Ulysses S. Grant, who was the president ex officio of the school, asking for justice. It worked. A week after sending the letter, Lockwood, 43, received her diploma, making her the second woman attorney in DC. By 1879, she would become the first woman to be admitted to the Supreme Court bar. In 1880, she argued a case before the Supreme Court, the first woman lawyer to do so.

Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsberg would later write in the forward of Belva Lockwood’s biography, “With optimism and tenacity, may we continue to strive as she did to advance our Nation and World the ideals of liberty, equality, and justice for all.”

As Lockwood opened a successful law practice and continued her work for universal suffrage, the national women’s movement was gaining steam. By the early 1880s, more and more women were running as candidates for local offices and by 1884, women held full suffrage in Utah, Washington, and Wyoming while fourteen states allowed them to vote in elections dealing with schools.

Marietta Stow, the president of the Woman’s Independent Political Party, announced herself as an independent for the governor of California. Stow knew her self-nomination was mere political theater, but she saw it as a tool for “creating positive momentum and that her completely legal bid for public office demonstrated the irony of voteless women candidates.”

That same year, Lockwood sent a letter to Stow, who also ran a progressive California newspaper, writing, “It is quite time that we had our own platform, and our own nominees.” Most women suffragists supported the Republican or Prohibition Party, not because they fully represented their views, but because they felt they had no better option.” Lockwood had recently endorsed the Prohibition Party nominee John Pierce St. John, who was running against Republican nominee James G. Blaine and Democratic nominee Grover Cleveland.

Sensing an opportunity to break from the conventional parties, Marietta Stow nominated Lockwood as the National Equal Rights Party candidate for president. Lockwood announced her acceptance in a letter, which the Washington Evening Star published on September 4, 1884. With her candidacy, she wrote, she pledged to “really and trully [sic] represent the interests of our whole people North, South, East, and West,” making the United States “in truth what it has so long been in name, ‘the land of the free and home of the brave.'”

In the weeks following her speech, Lockwood received national recognition. Harper’s Weekly wrote about her campaign, saying that she possessed “great force of character and indomitable perseverance.” While she knew that she would never get elected, she used her fame to call attention to otherwise ignored issues such as equal pay for women, citizenship for Native Americans and the allotment of tribal land, and of course, universal suffrage. In that sense, she filled the conventional role that third-party candidates do today.

Come election day in November of 1884, Lockwood convinced electors to pledge to her in at least seven states, including New Hampshire, California, Maryland, New York, and Oregon. She would end up getting nearly 5,000 votes. Grover Cleveland clinched the victory.

Belva Lockwood would run again in 1888 and continue to advocate for women’s rights until her death in 1917, just three years before the passing of the 19th Amendment. In 1914, when she was 84, she considered whether a woman would someday be president. “If [a woman] demonstrates that she is fitted to be president she will someday occupy the White House,” she said. “It will be entirely on her own merits, however. No movement can place her there simply because she is a woman.”

This story was largely reported through Jill Norgren’s biography “Belva Lockwood: The Woman Who Would be President,” along with newspaper stories and an autobiographical article in Lippincott’s Monthly Magazine. Video shot and produced by Evy Mages, featuring Sally Cusenza.