Give Donald Trump credit:

He seems to be shaking up Washington’s button-down culture and bringing an unruly heart back to life.

This is a city built for demonstrations, for protests, for grand celebrations, and for great sorrow. Washington’s first planner, Pierre Charles L’Enfant, saw to that with his sweeping Mall. Other planners and architects have filled L’Enfant’s empty spaces with the artifacts of national identity—the Capitol, the White House, the Washington Monument, the Jefferson and Lincoln memorials—and Americans with a message to send or a protest to lodge or who are just plain pissed off have been using those artifacts as backdrops to their anger, joy, or grief ever since.

Often, we can see the demonstration coming from miles—and weeks—away. As with the post-inaugural Women’s March, permits get distributed, street barricades set out. During the Vietnam War, the White House was on more than one occasion turned into a virtual fortress protected by a solid ring of DC Transit buses. For a while, tear gas seemed to be a permanent addition to the palette of local odors.

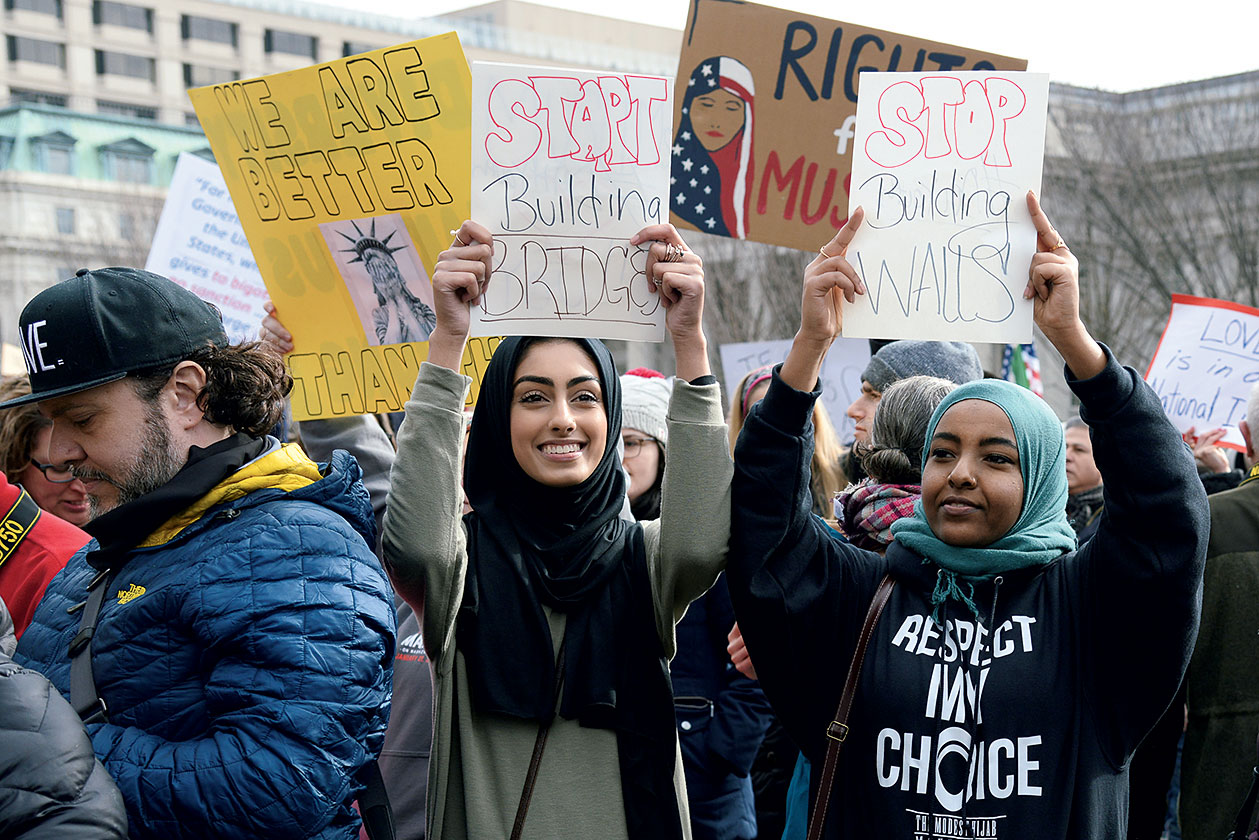

But it’s not always so organized. The kind of spontaneous crowds that gathered at local airports and outside the White House in the wake of Trump’s immigration ban have a long history here as well. Andrew Jackson almost didn’t survive his own swearing-in, so great was the mob that broke through the barriers at the Capitol to congratulate him. The draft-card torchers of the 1960s and ’70s were their natural heirs, as were the rioters who brought chaos within blocks of the White House following Martin Luther King Jr.’s assassination and the impromptu celebrants in Lafayette Square after Osama bin Laden was killed.

Democracy is meant to be messy and participatory—not just for the usual firebrands but also for students and stay-at-homes and little old ladies in tennis shoes. One could argue that the more placards we hold up, the more shoe leather we expend along the Mall and on Pennsylvania Avenue, and even the more tear gas we risk, the healthier our democracy really is.

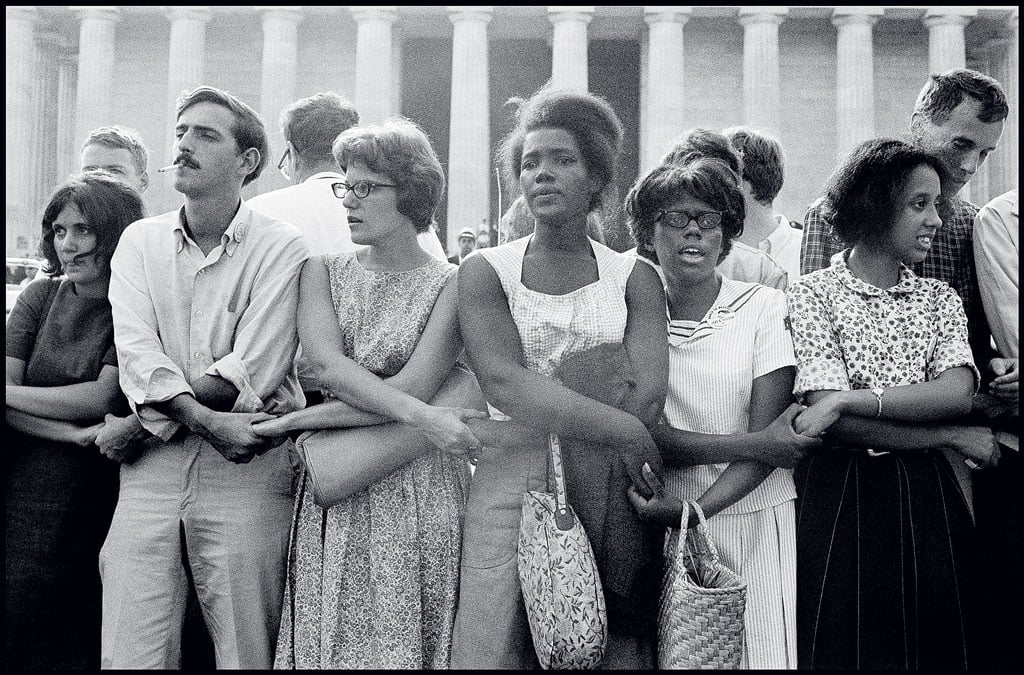

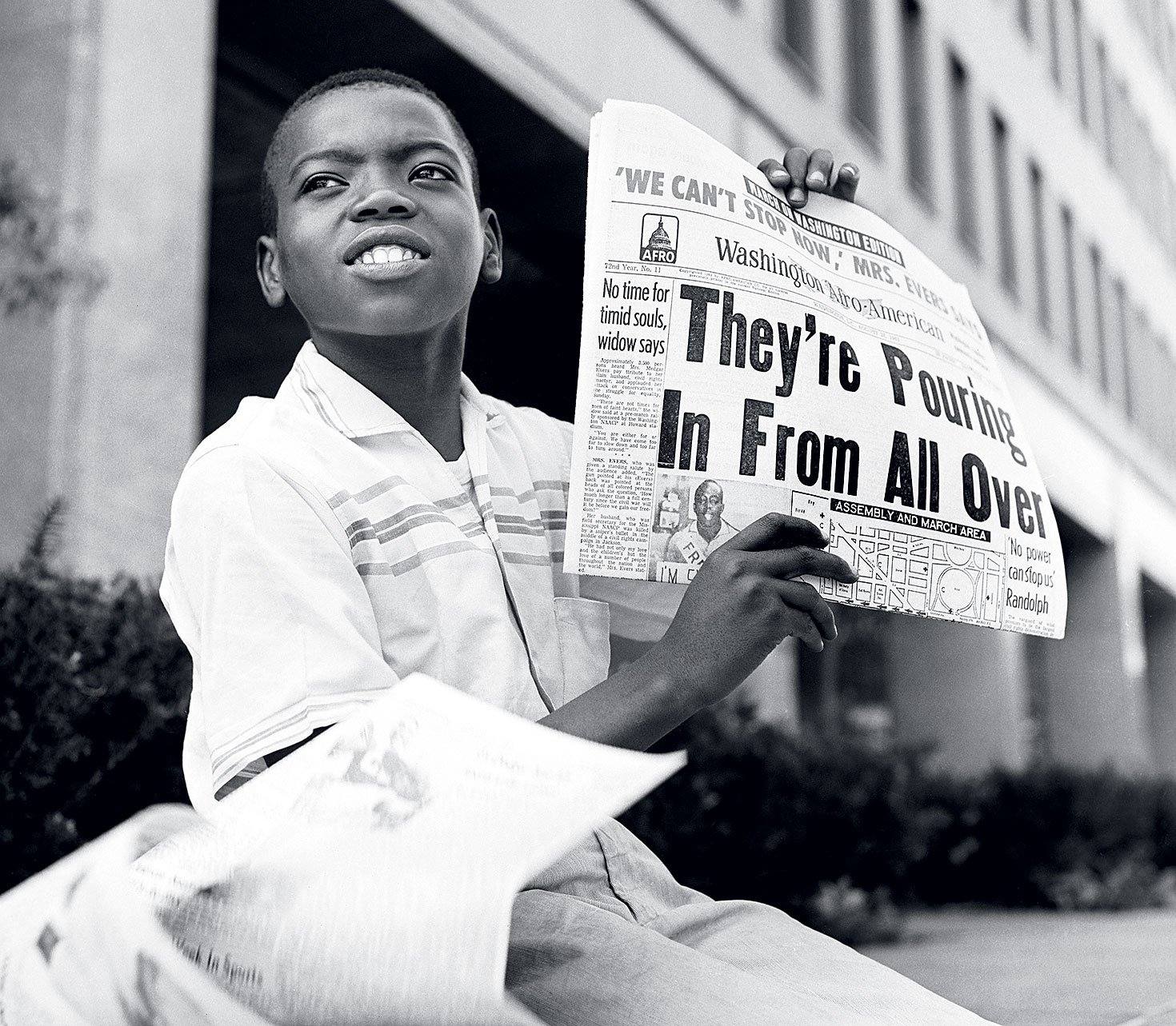

The 1963 March on Washington demanded more “jobs and freedom” and an end to racism.

An estimated 250,000 people, including those on 2,000-plus buses and 21 special trains, came in 1963.

Less than a year after the march, Congress passed the 1964 Civil Rights Act, banning discrimination.

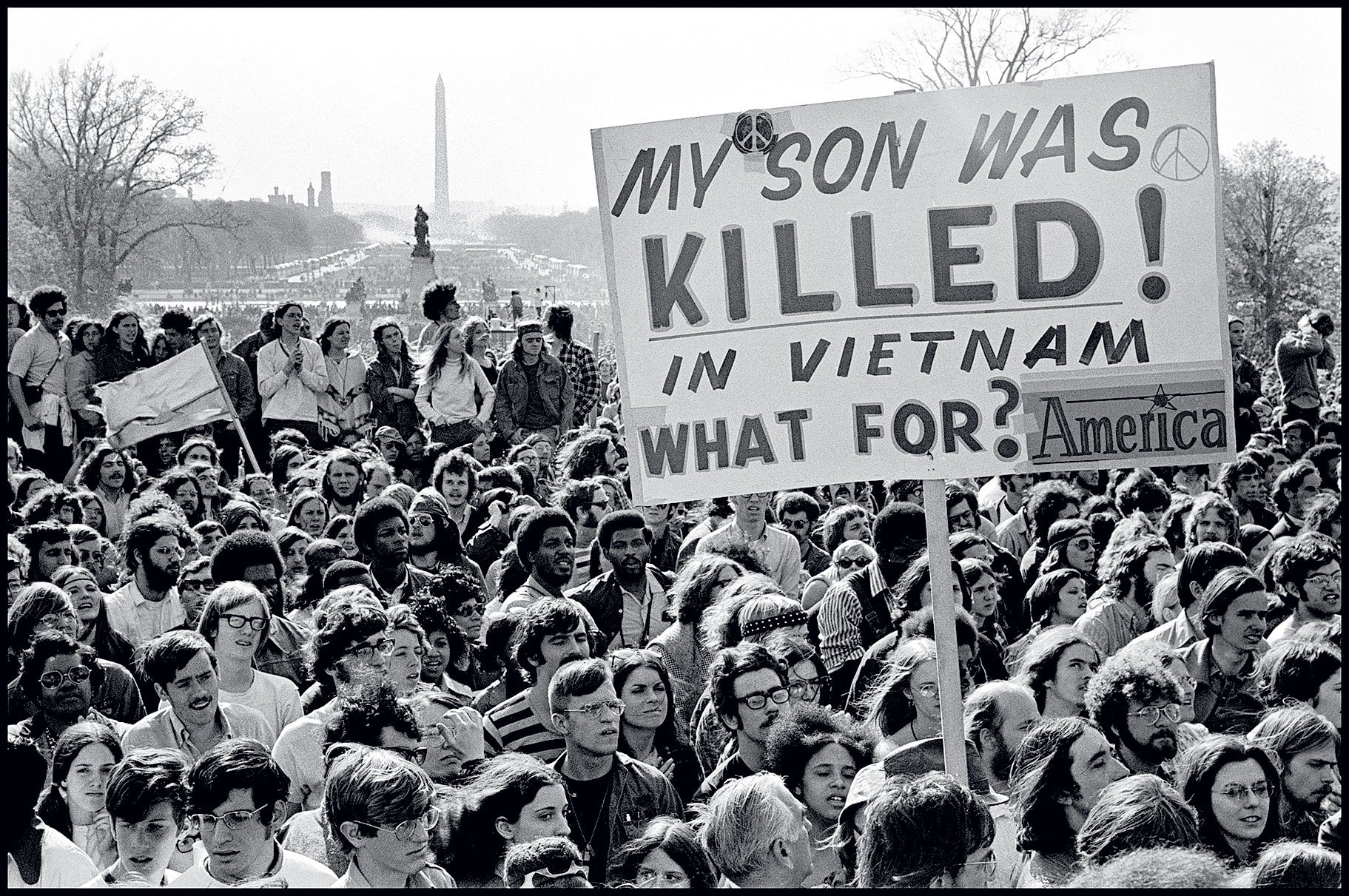

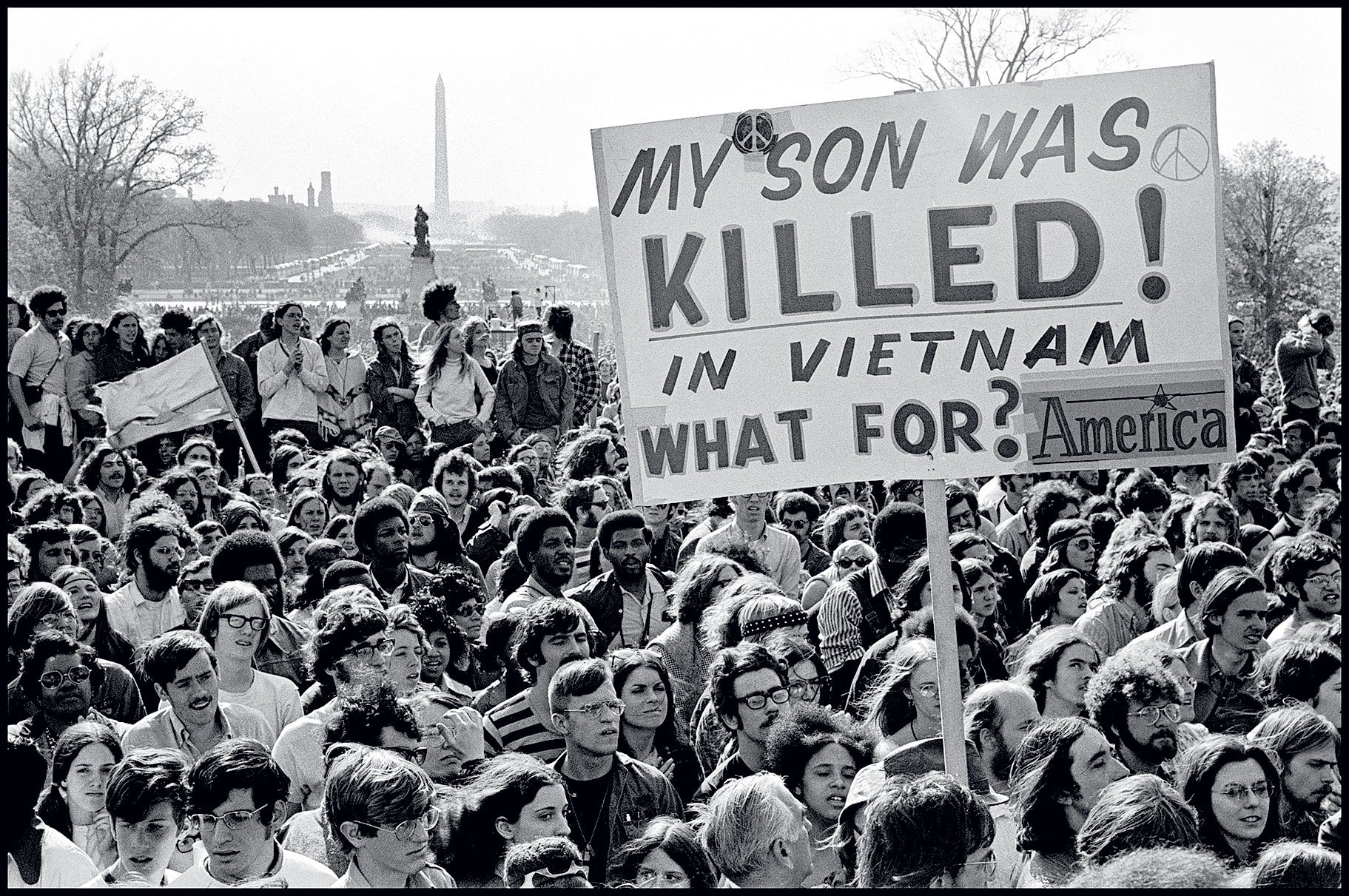

During the Vietnam War, demonstrations became part of DC’s landscape—as did tear gas.

For a 1969 “moratorium” day to end the war, an estimated 2 million marched nationwide.

A 1967 antiwar rally at the Pentagon inspired Norman Mailer’s The Armies of the Night.

Thousands took to the streets in DC and the nation for a 1970 Women’s Strike for Equality.

President Trump’s executive order temporarily banning refugees and certain immigrants triggered protests outside the White House.

Protesters also congregated at airports across the country, including at Dulles.

Believing “dance trumps hate,” Werk for Peace led a February dance party from the Trump hotel to the White House.

This article appears in the March 2017 issue of Washingtonian.