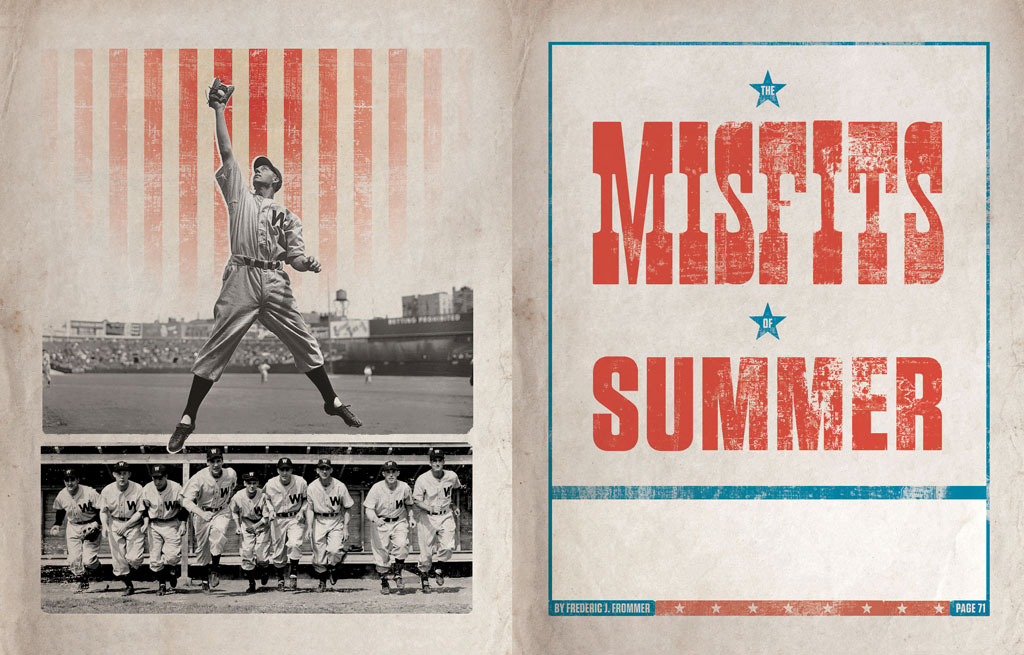

At the old ballpark on Georgia Avenue, workers were getting Griffith Stadium ready to host the World Series. The infield was resodded. Bleachers, put up to accommodate football games, were taken down. It was September 1945—less than a month after Emperor Hirohito surrendered to General MacArthur in Tokyo Bay—and an improbable Washington Senators team was on the cusp of winning the pennant.

It had been a long four years for baseball. With many of the game’s best players serving in the military, teams had spent World War II making do with ragtag substitutes. Some were too old for the draft. Others were classified 4-F—unfit for service. The era featured such eccentricities as a 15-year-old pitcher, a one-armed outfielder, and, in Washington, a one-legged player-coach.

Now, with the war over, the game and the country were slowly returning to normal. In the waning months of the conflict, players had started to come home. For Washington fans, it turned out, the most notable returning vet wasn’t on their team. Legendary slugger Hank Greenberg, just out of the Army Air Corps, had rejoined the Detroit Tigers. And on this last day of the season, it was Greenberg who stepped to the plate in the ninth inning of a game between his Tigers and the St. Louis Browns.

The game was more than 800 miles away, but Washington fans were paying attention. If St. Louis held its lead and won the second game of the doubleheader, the Senators would be one win from the World Series. If not, Washington was done. Alas, it wasn’t to be. Greenberg hit a grand slam, giving the Tigers the game—and ending Washington’s season. By the next spring, as regulars replaced wartime understudies, the team would return to its usual mediocrity.

But today, those 1945 Senators are suddenly a bit more relevant. Last year, the Chicago Cubs won their first World Series in more than a century. Which means the longest championship drought is now owned by Washington, a city that last claimed a World Series in 1924—a span interrupted by only a few decades in which the capital didn’t have any team at all.

This is the story of the Washington club that almost sneaked into the World Series, and the surreal moment in American history when it won the city’s affection.

![]()

The United States was a nation in grief when baseball kicked off the 1945 season, just days after the death of Franklin D. Roosevelt.

Not much was expected of the team playing in Roosevelt’s capital. The old saw about Washington was “first in war, first in peace, and last in the American League.” The Senators (their official name was actually the Nationals) had lived up—or rather, down—to that standard the previous year: They were coming off a last-place finish in 1944. That war-depleted team had been so desperate for players that owner Clark Griffith signed Eddie Boland, who had been playing for the New York City Sanitation Department team. (Boland didn’t do too badly, actually, hitting .271 in 19 games.)

Griffith had also signed 17-year-old Eddie Yost, who would go on to have an admirable career. Naturally, Yost was soon called into the military. So when 1945 opened, he wasn’t there.

the team hit 27 home runs all season–what bryce harper does in an off year. in the bad news bears world of wartime baseball, it didn’t much matter.

At the Senators’ April 20 home opener, Washington ballplayers wore black armbands and dedicated the game to FDR. A band played taps. Two Marines and a Navy corpsman who had erected the flag at Iwo Jima, fresh off a visit to the White House to meet new President Harry Truman, received a thunderous ovation from the 24,494 people at the game.

Truman didn’t accompany them, though. Since Pearl Harbor, baseball hadn’t been observing the presidential tradition of throwing out the first pitch, because of the gravity of the times. Instead, House speaker Sam Rayburn handled the duties, flanked by then-congressman Lyndon Johnson and others. Sporting a three-piece suit and a Washington baseball cap, Rayburn tossed the ball to a group of ballplayers but overshot them. Pitcher Santiago Ullrich made a nifty catch with his back to home plate.

The Senators didn’t do much better, losing 6–3. To the surprise of no one, it looked like Washington was off to another ho-hum season.

![]()

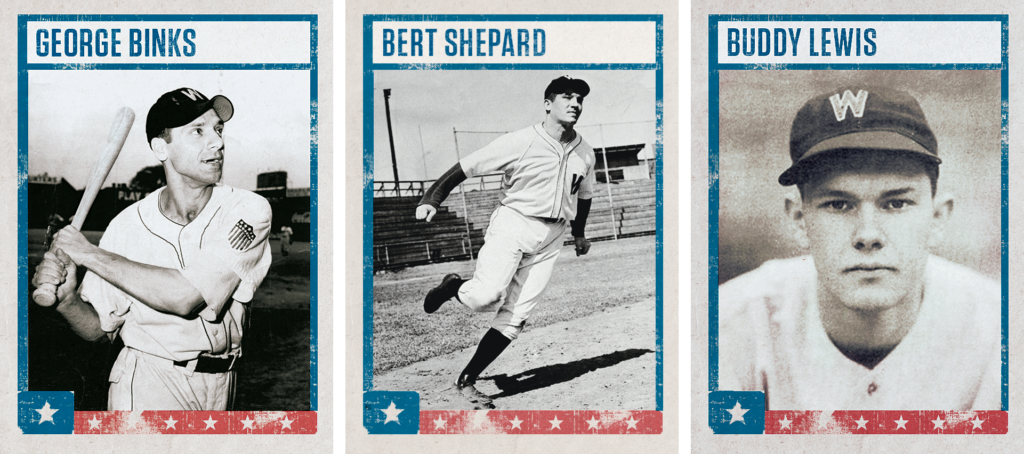

Fans who squinted closely enough at the early box scores, though, had reason to be optimistic. The team’s oddball roster included a new outfielder, George “Bingo” Binks, who was soon hitting .400. The year before, in the minors, Binks had hit .374 to lead the league.

Born George Binkowski, Binks was the kind of guy who could shine while the stars were fighting overseas. He had dropped out of high school after just one year to start playing for a sandlot team with grown men to earn money for the family during the Great Depression. Now a 30-year-old rookie, he was ineligible for military service because he was deaf in one ear. He’d spent the first two years of the conflict working as a machinist in a war-materials factory.

In Washington, he quickly became a favorite of fans—they would chant, “We want Binks!” when he was out of the lineup. But he constantly irritated the team’s old-school manager, Ossie Bluege. Binks would throw to the wrong base, swing when he got the bunt sign, and generally drive Bluege crazy.

“He’s an enigma to me,” Bluege told Washington Post columnist Shirley Povich. “I’ve felt like benching him a dozen times for some of the things he does wrong and some of the things he doesn’t do at all, but I’m scared to keep him on the bench. It could be the wrong thing to do, because he has a lot of ability.’’

Chewing Binks out didn’t work, either: “After I bawl him out, he says to me, ‘I haven’t heard a word you said.’ ”

The year before, Binks had had a similar effect on his minor-league manager, Casey Stengel, who would go on to fame leading the dominant New York Yankees teams of the ’50s. “I can read the temper of friends, the whims of women, and the changes of weather, but I cannot predict what George Binks will be up to next,” said Stengel, who dubbed Binks “Baseball’s Magnificent Unpredictable.”

In 1945, Binks would lead the Senators in RBIs, hits, and doubles and would finish in the league’s top ten for RBIs, hits, total bases, stolen bases, and extra-base hits.

His style of play would also prove representative of the team—and effective in the Bad News Bears world of wartime baseball. Washington hit only 27 home runs all year, barely more than what the Nats’ Bryce Harper got all last season in an off year. Amazingly, only one of those homers came at home—and it was an inside-the-park home run. Instead of power, the team relied on speed and hustle, leading the league in scrappy stats like triples and stolen bases.

Still, by May 8, the day after the Nazis surrendered in Europe, the team was only 9–9, mired in fourth place.

![]()

The victory in Europe didn’t spell the return of normal baseball. THERE’S STILL A WAR ON! STAR ATHLETES WILL BE POLICING EUROPE OR FIGHTING JAPS FOR LONG TIME TO COME, declared the headline above an AP story the next day.

But even as the Pacific war continued, some players started to trickle back. “I sure missed all this,” Washington outfielder Buddy Lewis said when he returned in July from a stint flying cargo planes across the Himalayas into China. “The smell of sweaty bodies, rubbing alcohol is a lot healthier than the stink of dead, burning bodies. It’s great to be back. To be a free man once again.”

While flying missions overseas, Lewis had named his C-47 cargo plane “the Old Fox,” the nickname of Clark Griffith, the Senators’ owner. A few days after Lewis came back, on July 31, Griffith returned the favor by honoring him at Griffith Stadium, where the tightfisted owner gave the outfielder a $500 war bond. “This is the moment I have been praying for,” Griffith said, choking back tears.

“I felt something like I did when I played in my first big-league game,” Lewis said. “But I got over that tight feeling after I was up a while. Now that I’m back, I’ll get over it again. That’s the way I feel, just like I’m breaking in again.” His return got the team hot. He hit .333 over the last 69 games of the season and fit right in with the team’s offensive style, swatting seven triples of his own.

The wartime pitching squad also relied on an unusual bag of tricks. Four of the starters—Roger Wolff, Dutch Leonard, Mickey Haefner, and Johnny Niggeling—were knuckleballers. Instead of the blazing fastballs of traditional aces, their pitches fluttered and spun in order to confound batters, which in that season of substitute teams proved effective: The quartet pitched 60 complete games among them and helped the Senators to a league-best 2.92 ERA. The rotation’s sole non-knuckleballer, a five-foot-seven Italian-born rookie named Marino Pieretti, won 14 games.

By the beginning of August, Washington was in third place. True, they were just a middling four games over .500, but it was better than dead last.

![]()

The Senators finally hit their stride during a kooky scheduling run that could never happen in modern times.

Thanks to Griffith, they were slated to host five doubleheaders in five days, with no rest. The owner wanted to end the season a week early in order to rent his stadium to the Redskins. So his team was in for ten games in five days, “an unholy burden on their skimpy pitching staff,” in Povich’s words. The team would play an additional nine doubleheaders that month, most of them on the road.

The Senators thrived in the heat, winning nine of the ten games. But the most historic moment came during their sole loss. In the second game on the fourth day of the doubleheader glut, the Red Sox were leading 14–2 and had loaded the bases in the fourth inning. Bluege, the Washington manager, had no fresh arms in the bullpen, so he turned to Bert Shepard, a player-coach who hadn’t appeared in a game all season. For good reason: Shepard had had his right leg amputated under his knee after being shot down in Germany during the war.

So what was he doing on a baseball diamond? After returning to the states, Shepard had been taken to Walter Reed Hospital for an artificial limb. While there, he received a visit from Undersecretary of War Robert Patterson, who asked Shepard what he wanted to do after the war. A former minor-league pitcher, Shepard said he wanted to play again, so Patterson called Griffith and asked if he’d give the 24-year-old a tryout. After Shepard held his own, the team signed him as a player-coach.

Playing him was another story. During the season, he often pitched batting practice, and occasionally pitched in exhibition games, but this was his major-league debut.

Striding and landing on his artificial limb, Shepard struck out a Boston player named George “Catfish” Metkovich to end the rally, receiving a standing ovation from the 13,000 fans. He pitched the rest of the game, giving overtaxed teammates some much-needed rest and holding Boston to just one run in the process. Though he went on to pitch a few more seasons in the minor leagues, that was Shepard’s first and last performance in the majors, his lifetime ERA frozen at an outstanding 1.69.

Reflecting on the performance decades later, Shepard told the International Herald Tribune “there was much more pressure on me than it seemed,” despite entering a lopsided game. “If I would have failed, then the manager says, ‘I knew I shouldn’t have put him in with that leg.’ But the leg was not a problem, and I didn’t want anyone saying it was.”

Riding the 9–1, five-day homestand, the Senators sprinted past the Yankees to second place on August 5, just a half game behind the first-place Tigers.

![]()

The following day, the United States dropped the atomic bomb on Hiroshima. On August 15, Emperor Hirohito broadcast his surrender announcement, formalized aboard the USS Missouri in Tokyo Bay on September 2.

Six days later, Truman threw out the first ball at a Senators game against his home-state St. Louis Browns—the first time a President had made the traditional pitch since before the war. At the regular White House staff meeting that morning, Truman’s assistant press secretary, Eben Ayers, wrote in his diary, “The president was in excellent humor and seemed especially chipper. He commented that he felt better than he had in a week. Someone commented on the fact that he was going to the ball game this afternoon, and he said he was going to ‘pull for St. Louis’ and ‘the Madam’ for the Nationals.” The Madam was Truman’s wife, Bess.

The appearance of the smiling President taking in a Saturday-afternoon ball game served to reinforce the impression that things were back to normal. Before the game, Truman received a huge ovation from the big crowd, and players from both teams lined up in front of his box, caps over their chests. During the game, Truman, in a suit and Panama hat, chewed gum, drank soda, and mimicked a fine backhanded play by right fielder Lewis in the ninth inning.

George Binks, who didn’t play that day, was assigned near Truman’s box with a first baseman’s mitt, to make sure the President didn’t get hit by a foul ball, according to his son, George Binks Jr. The ballplayer and the President chatted amiably. “My dad said he was just a regular guy, using regular language, none of the highfalutin stuff,” Binks Jr. says. At one point, Truman said to Binks Sr., “Let me see that glove—I could catch one with this son of a bitch.” Binks told his son that the President would become especially excited when a veteran came up to hit. “He’d get up and wave his hat and cheer,” says Binks Jr.

Washington won 4–1 and, with two weeks to go, trailed the first-place Tigers by 1½ games.

On September 23, the final day of Washington’s baseball season—but not the rest of baseball’s—the Senators took on the Philadelphia Athletics in yet another doubleheader. Washington needed a sweep to pull into a first-place tie with the Tigers. In the bottom of the 12th inning of game one, Philadelphia’s Ernie Kish lofted a fly ball to center field, where Binks was playing. The sun had come out from behind the clouds a little while before, but Binks had forgotten his sunglasses. He lost the ball in the bright sky. Kish wound up with a double and later scored the winning run.

“He said he took his sunglasses out of his pocket to hit because he didn’t want to destroy them if he had to slide into a base,” his son Terry recalls. He adds that his dad said the glasses wouldn’t have helped anyway because the ball was hit directly in the middle of the sun and he wouldn’t have been able to pick it out either way. But some still blamed Binks for the loss in the crucial game.

“No matter how hot it gets, the sun will never again warm up the Washington Senators,” the AP cracked.

With their season over, all the Senators could do was hope the Tigers hit a skid. If Detroit lost its final four games, Washington would finish in first place — and in those days, before divisional play, would go straight to the World Series as the American League pennant winners. More realistically, if the Tigers were to go 1–3, the two teams would finish in a tie, leading to an all-the-marbles game to determine the pennant.

![]()

The Tigers split the first two of their games, giving the Senators and their fans hope. Among the most bullish partisans was Griffith, the 75-year-old owner. Back in 1912, he’d bought a 10-percent ownership of the Senators and taken over as manager, leading the team to its first winning season. But he really made his mark as an executive, eventually becoming president and majority owner. Griffith put together three pennant-winning teams in the 1920s and ’30s, but by the ’40s he was outgunned financially by richer owners who didn’t rely on their teams for their livelihood. Griffith was forced to run the team in a skinflint manner.

So it was a real gesture of faith when the owner had his staff get the ballpark ready for postseason. He announced he’d start selling World Series tickets at 6 pm the evening after the playoff game. “We’re going to be in there yet—in the playoff and in the Series. I just feel it in my bones,” he said.

Then Greenberg hit his grand slam in St. Louis, and neither the playoff game nor the World Series came to pass.

Washington returned to business as usual: an October without baseball. The Tigers went on to win the Series.

The following year, the Senators dropped to fourth place. Binks lost his starting position to Stan Spence, who had returned from the Army. Playing as a reserve, Binks hit just .194 and was traded the next year. “He got a bad rap as the one that lost the pennant,” his son Terry says. “Because in the same game there were other mistakes made also. His favorite saying was ‘In baseball, one day you’re a hero, and the next day you’re a bum.’ ”

The same was true for the entire team. The city would see just two more winning seasons over the next quarter century. In a further ignominy, Washington would then endure 33 years without baseball, cast as a city that couldn’t support a team.

The 1946 season did feature one carryover from the previous year. Capitalizing on the recent pennant race, the Senators drew just over 1 million fans, the standard back then for a good attendance mark. It was the only time a Washington team hit that milestone in the 20th century.

Last year, the Nats—who opened the season with a much greater likelihood of winning it all—drew nearly 2.5 million.

Frederic J. Frommer is head of the Sports Business Practice at the Dewey Square Group, a public-affairs firm, and author of “You Gotta Have Heart,” a history of Washington baseball, on which some of this story is based.

This article appears in the May 2017 issue of Washingtonian.