Recently, I was reading my 4-year-old son a book I loved as a child, Hugh Lofting’s The Story of Doctor Dolittle. The first few chapters unfolded as I remembered. It was a sweet, sometimes silly saga of doctor who can speak to animals and cures them of their ills. Sure, the language seemed stilted by modern standards, but it was an otherwise timeless tale that seemed to be bringing him as much pleasure as it had once brought me.

But then Dr. Dolittle heads to Africa to help the monkeys overcome a mysterious deadly disease laying waste to their population. He is captured by the Jolliginki tribe and taken before their leader. When I flipped the page and saw the illustration of the king and his wife–their lips and ears oversized, their bodies muscular, yet somehow misshapen–I realized the illustrator saw them as caricatures, not characters. So did the author, who described them using shallow stereotypes that would once have been charitably referred to as the product of a colonialist worldview, but now would simply be called racist.

I stopped reading, horrified.

My wife was understandably angry that I had gone as far as I had. We were both disgusted by the characterization of the African characters in the book, but for her it was personal–she was born in Ghana in western Africa. I’m of nebulous European stock, so our son is biracial, his skin a royal bronze. We are very careful in choosing the books we read to him and we to stock his library with as many titles featuring children of color.

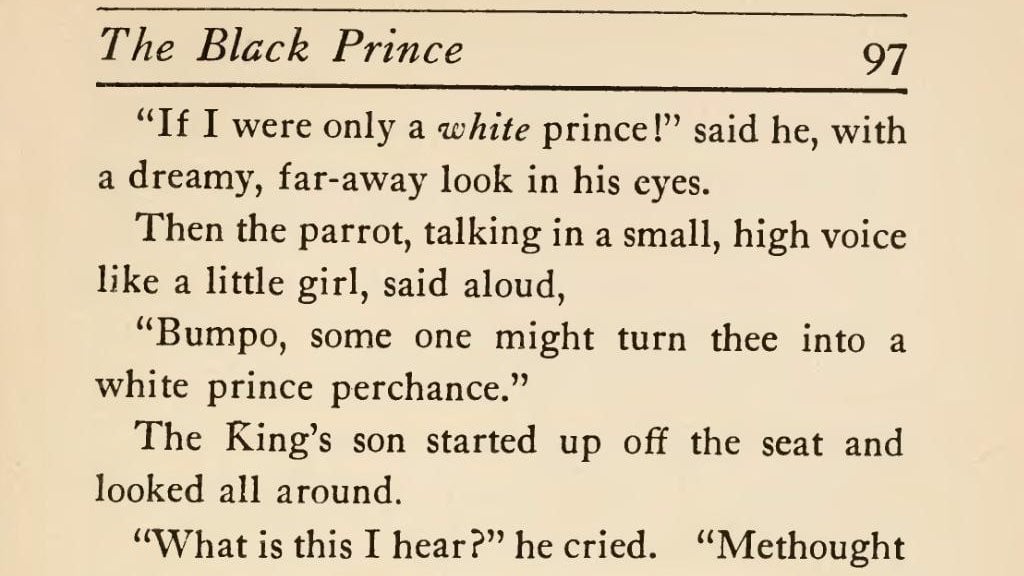

It’s lucky I didn’t go any further in The Story of Doctor Dolittle. After escaping the tribe, the doctor is ultimately recaptured by them. However, he gives them the slip again with help from the king’s son, who asks the doctor to bleach his skin white in return, so he can look like one of the fairytale princes he admires.

Yikes! That is not what I want to be reading to my boy.

I didn’t know I had been so ignorant, insensitive and immune as a child to the inherent racism in this story. Though, to be fair, I didn’t really start thinking about race, the history of race relations, and issues of racism until I was a teenager. I’m sure a lot of children have read Doctor Dolittle and simply thought it was a fanciful story without considering its colonialist construct and racist stereotypes. Unless an enlightened parent or teacher points those elements out to a younger reader, it may go over their heads completely.

As I’ve gone through some of my favorite childhood books looking for other titles to share with my son, I realize that Doctor Dolittle is not alone. As I read through my once-beloved Tintin graphic novels, I discovered its creator, Hergé, also possessed what one might call a less than enlightened worldview. The African characters of Tintin in the Congo were cartoonish lampoons with oversized pink lips and constant expressions of dumbfounded surprise, while Tintin in America features stereotypical depictions of Native Americans. Even Babar wasn’t immune. Several of picture books featuring the generally jolly elephant are littered with racist images of black people.

Though these books don’t present a worldview I want my son to believe is normal, they can be useful. When such negative stereotypes or degrading depictions are presented, parents should use them as teachable moments. Depending on kids’ ability to digest the information, moms and dads should explain the historical context that gave rise to these destructive characterizations, how they come from a place of ignorance, and why they are wrong. These moments very well may spark a bounty of questions and inspire conversations that continue long after the book is finished.

Even though we didn’t finish it, I’m glad I started reading The Story of Doctor Dolittle. It opened my eyes to my ignorance in the past, while teaching me how to be a more enlightened parent going forward.