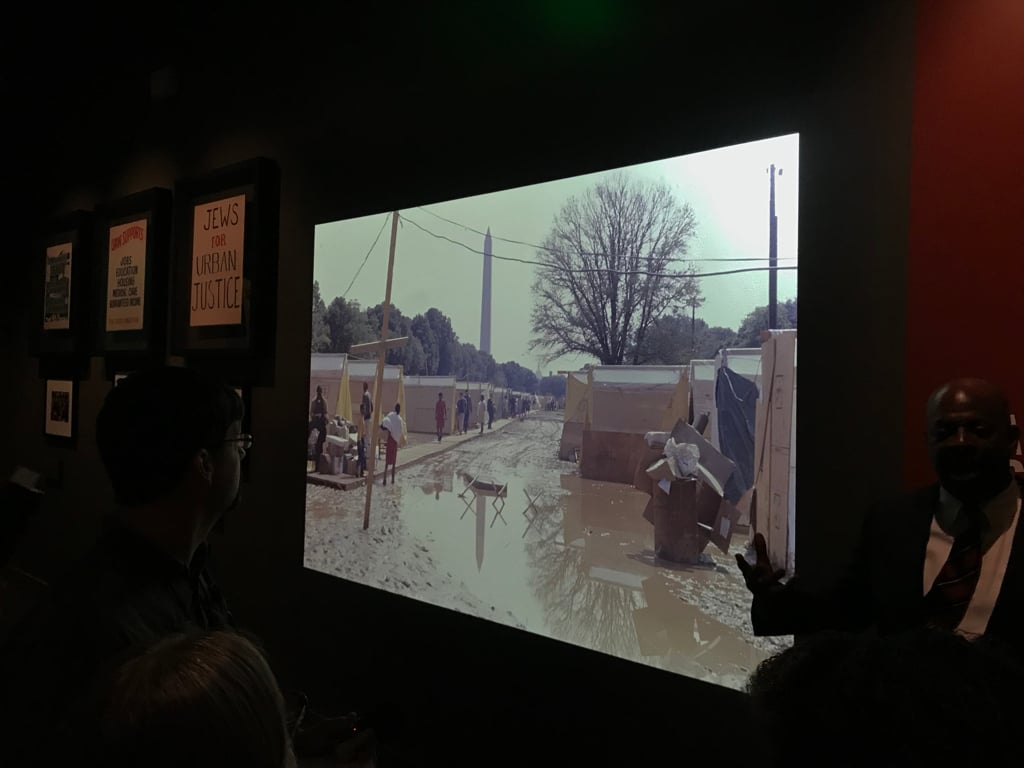

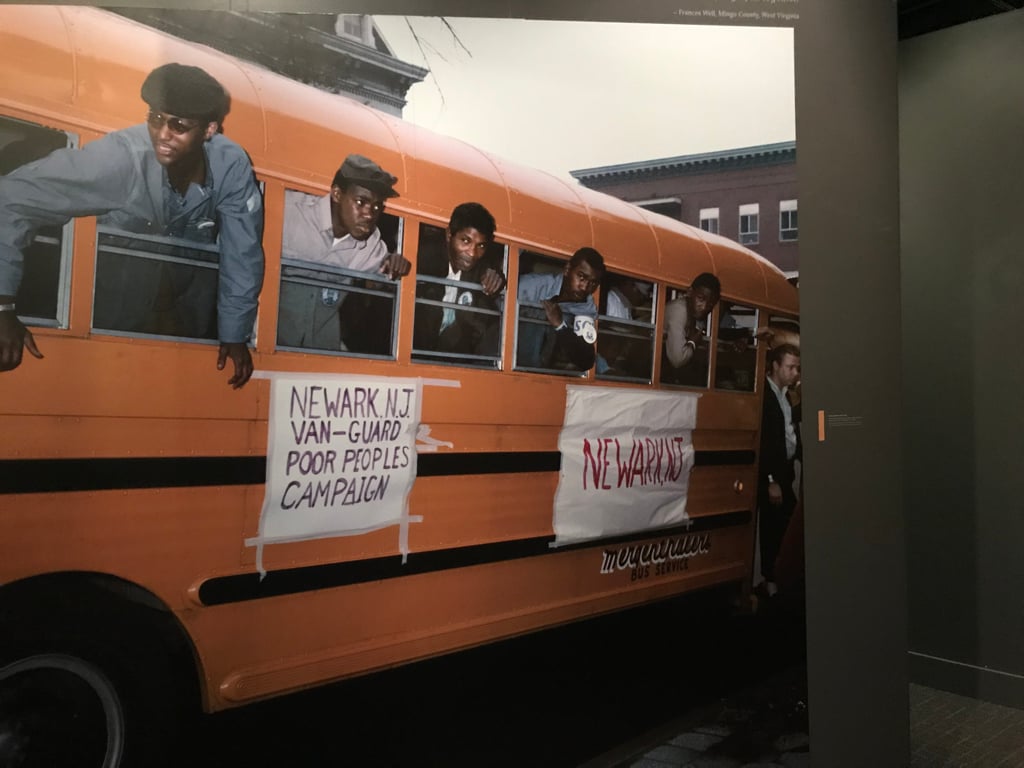

On May 12, 1968, five weeks after the death of the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., 3,000 activists from all over the country poured onto a swath of the National Mall just below the Reflecting Pool to carry out one of King’s final plans. The demonstrators erected a temporary tent city on the Mall, complete with functioning electrical and sewer lines, a town hall, dining establishments, and a day-care center. They called it Resurrection City, and for nearly six weeks, inhabitants used their stay to draw the nation’s attention on poverty.

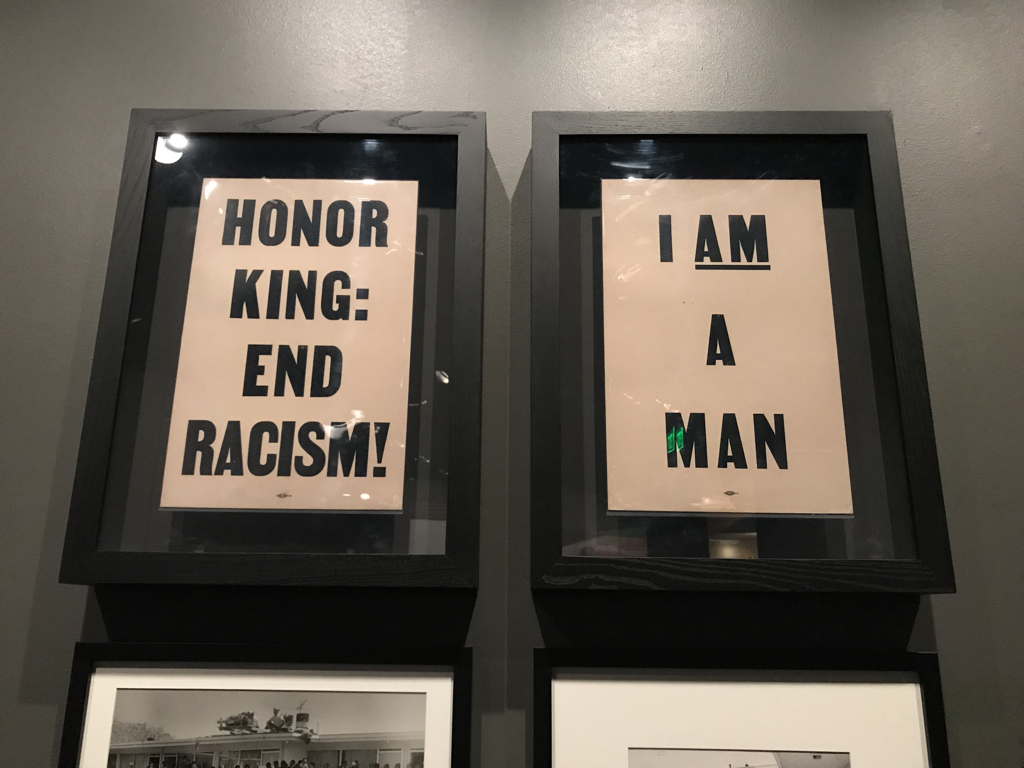

This week, the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture opened “City of Hope,” an exhibit full of photographs, oral histories, and physical artifacts from the encampment, timed to the 50th anniversary of King’s death and the Poor People’s Campaign. Visitors can check out panels of large-scale murals, placards issued by labor unions and social-organizing groups wooden panels that propped up the tents, and selections from a trove of nearly 1,600 newly rediscovered photographs, many of which had been sitting in the Smithsonian Institution’s archives since the 1970s. (While a project of the African-American history museum, which still requires a timed pass for entry, this exhibit is located inside the more easily accessible National Museum of American History.)

While the African-American history museum features a couple panels on Resurrection City in its main gallery, the encampment is not always remembered among the most famous moments of the Civil Rights Movement, despite occupying a huge chunk of the Mall for much of a wet and muddy springtime. “We want to make people aware this event happened,” says Aaron Bryant, the exhibit’s curator. “Generally in the history books Martin Luther King did these things, and he died, and that was the end of civil rights. We never really talk about there was an actual movement after his assassination, and there was a legacy that we’re still dealing with today, that we still have benefits of today, that we can learn from.”

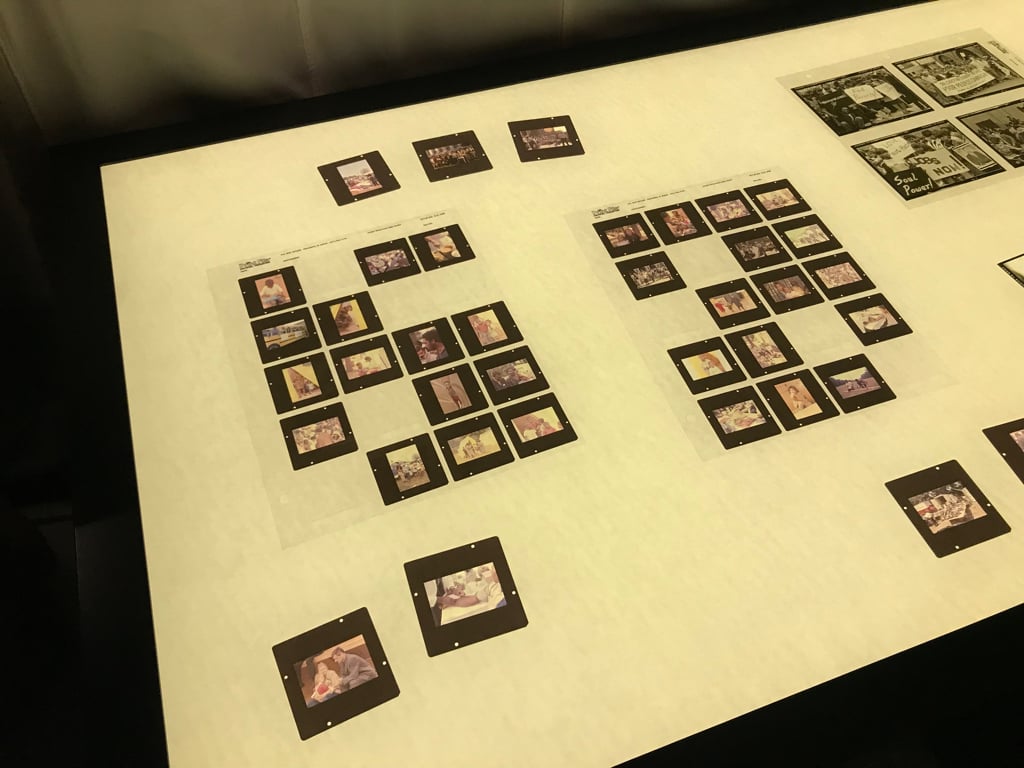

The exhibit is launching with five oral histories, including recollections from former Resurrection City residents Marian Wright Edelman, who went on to found the Children’s Defense Fund, and Andrew Young, the future congressman and US ambassador to the United Nations. (More will be added as the exhibit stays open, the Smithsonian says.) The photography is also novel for a civil-rights exhibit, Bryant says. The best-known images of the Civil Rights Movement tend to be black-and-white and taken by men, Bryant says; many of the unearthed photos displayed in “City of Hope” are full-color and were captured by women, including Jill Freedman, Laura Jones, and Clara Watkins.

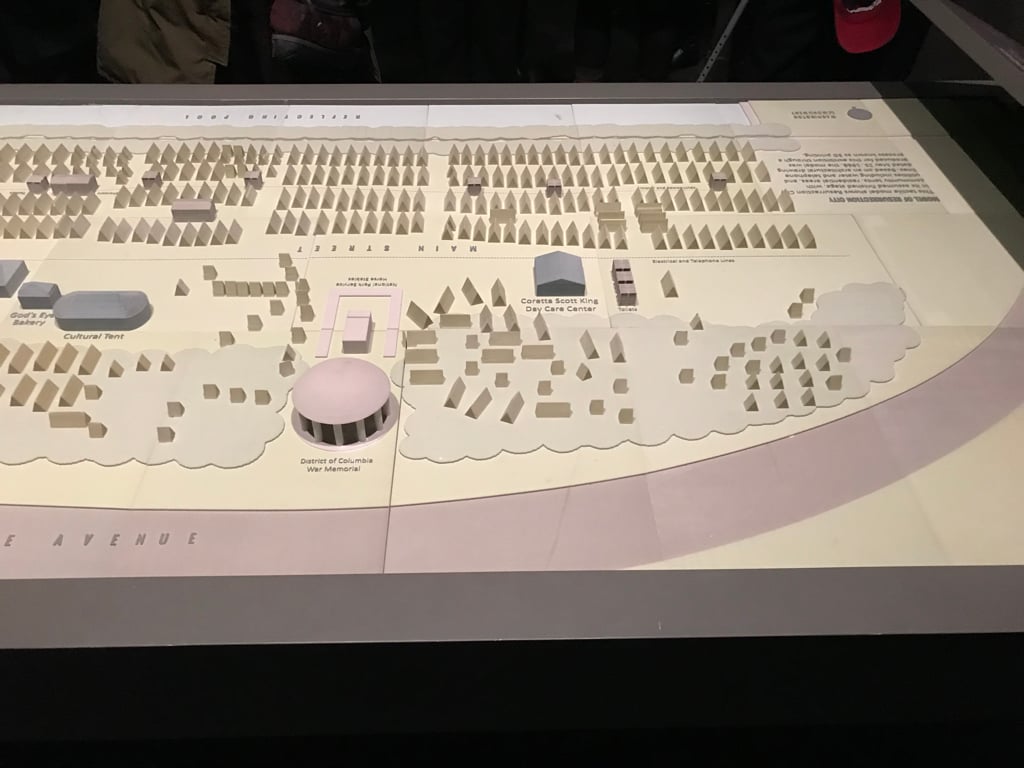

At the center of the exhibit is a scale model of the encampment, featuring rows of tents, drawings of the utility lines, and the facilities erected over the course of the demonstration, including a bakery and a daycare center named for King’s widow, Coretta Scott King.

“All these memories came flooding back about where we were,” says Marc Steiner, a Baltimore radio host who joined Resurrection City as a 22-year-old activist.

Besides bringing back a chapter of the national Civil Rights Movement, “City of Hope” also tells a story about DC’s history. Erected just weeks after the city burned in riots following King’s assassination, Resurrection City filled downtown DC with people pleading with the government to address systemic poverty. The exhibit performs a function that many DC museums miss out on, says Lonnie Bunch, the NMAAHC’s director.

“I’ve always felt that museums in Washington often forget they’re in Washington,” he says. “It was really important to me to do work like this that allows people to understand that this was a national story, but it’s also a local story. And our hope is that hopefully we can illuminate more how Washington as a city is both a site of change and also a source of change.”