The affliction affects nearly 50 percent of women in their lifetime, yet it’s rarely discussed beyond the hushed confines of the salon chair: female hair loss, which can be caused by a range of factors, from the seemingly uncontrollable (hormones) to the seemingly innocuous (too many top-knot buns).

“For women, hair is a security blanket,” says Lily Talakoub, a board-certified dermatologist at McLean Dermatology & Skincare Center. “More women have cried in my office from hair loss than anything else.”

Until recently, the main options to treat hair loss in women were topical foams such as Rogaine, which was originally developed for men, and hair transplantation, an often expensive surgery that can lead to infection or scarring.

But last year, research emerged showing the success of a new therapy for hair loss in women: platelet-rich plasma. At the time, PRP had already made its way into microneedle facials, because it’s a proven powerhouse in stimulating collagen production. Last year’s research, first published in the International Journal of Women’s Dermatology, cited seven recent studies that demonstrated positive results in using PRP for hair loss, too, pointing at growth factors in PRP that stimulate follicles and encourage new hair growth. There’s a reason the treatment is known in some medical offices as “liquid gold.”

PRP is particularly effective in combatting female-pattern hair loss, the less talked-about equivalent of male-pattern baldness. In male-pattern baldness, hair recedes in an “M” pattern near the forehead or falls out in a circular pattern at the top of the head; in women, hair thins at the part line or, for some, all over. Androgenetic alopecia, the medical term for this kind of hair loss in both sexes, is caused by fluxes in androgens, hormones that play a role in sexual function and hair growth. While a treatment such as Rogaine tackles both male- and female-pattern hair loss—experts are still unsure how the treatment works—it comes with unpleasant side effects, such as hair in unwanted places and weight gain. PRP, on the other hand, is shown to have minimal side effects or recovery downtime.

Talakoub estimates she has treated more than a thousand hair-loss patients with PRP, most of them women. How does it work? The doctor draws a patient’s blood and spins it in a centrifuge, separating the PRP from the rest of the blood. Then she injects the PRP into follicles at the site of the hair loss. Talakoub says it usually takes one treatment a month over the course of five months to see new hair growth. (The aforementioned research reports an average of three months.) A single treatment costs about $200, and like most hair-loss treatments, it’s not covered by insurance.

PRP is also effective in stimulating hair growth due to loss after pregnancy or from stress, as long as the follicle is still alive. (“If the scalp feels like a baby’s bottom, you’re not going to grow it back,” Talakoub says.) At any given time, around 90 percent of hair is growing, while the other 10 percent is in a resting phase. This resting hair typically falls out every two to three months. During pregnancy, estrogen—which plays a protective role in hair loss—peaks and prevents the resting hair from falling out, which is why many women report thicker hair during pregnancy. When estrogen levels balance out after childbirth, the resting hair may fall out all at once, a process called telogen effluvium. For most women, the loss of resting hair isn’t noticeable, but for some, the resting hair actually comprises 60 percent of all hair—and losing more than half a head of hair can be alarming and stressful.

PRP can also help hair loss caused by physical stress, such as a car accident that shocks the body, or emotional stress, including anxiety and depression. Then there’s a sneaky culprit that directly stresses the follicles: hair ties. “Anytime you put your hair back, you’re pulling on the hair follicle. Over time, the follicle can die,” says Talakoub, noting that in addition to ponytails or buns, extensions and braids can stress the hair follicle and “kill” it: “If the actual follicle has died, it’s very hard for that hair to come back.” She suggests wearing hair in a loose ponytail or pulled back by a headband.

Feed Your Head

Surprise: Eating more corn chips can be good for hair. Plus four other foods to add to your diet.

It’s well known that diet can play a big role in hair health. We asked Addie Claire Merletti, a registered dietitian at Vida Fitness, to recommend foods that feed hair. Her suggestions come with a caveat: Before adding micronutrients to what you eat, she advises having a health-care professional weigh in on your overall diet. She also recommends looking at the supplements you ingest, because too much selenium, vitamin A, and vitamin E have been linked to the opposite result—hair loss.

Lentils

“Lentils are high in iron, which is the world’s most common deficiency and a documented cause of hair loss,” says Merletti, noting that getting enough iron is especially important for vegans.

Oysters

“Oysters contain more zinc than any other food,” she says. Zinc is an essential mineral, and zinc deficiency—which can either be inherited or acquired—is correlated with hair loss. Other zinc-heavy foods she suggests are red meat, poultry, navy beans, and pumpkin seeds.

Eggs

Eggs are extremely high in biotin, next to only liver, says Merletti. She notes that while biotin is in many hair-growth supplements, no clinical trials have shown efficacy in treating hair loss with biotin supplementation in the absence of deficiency.

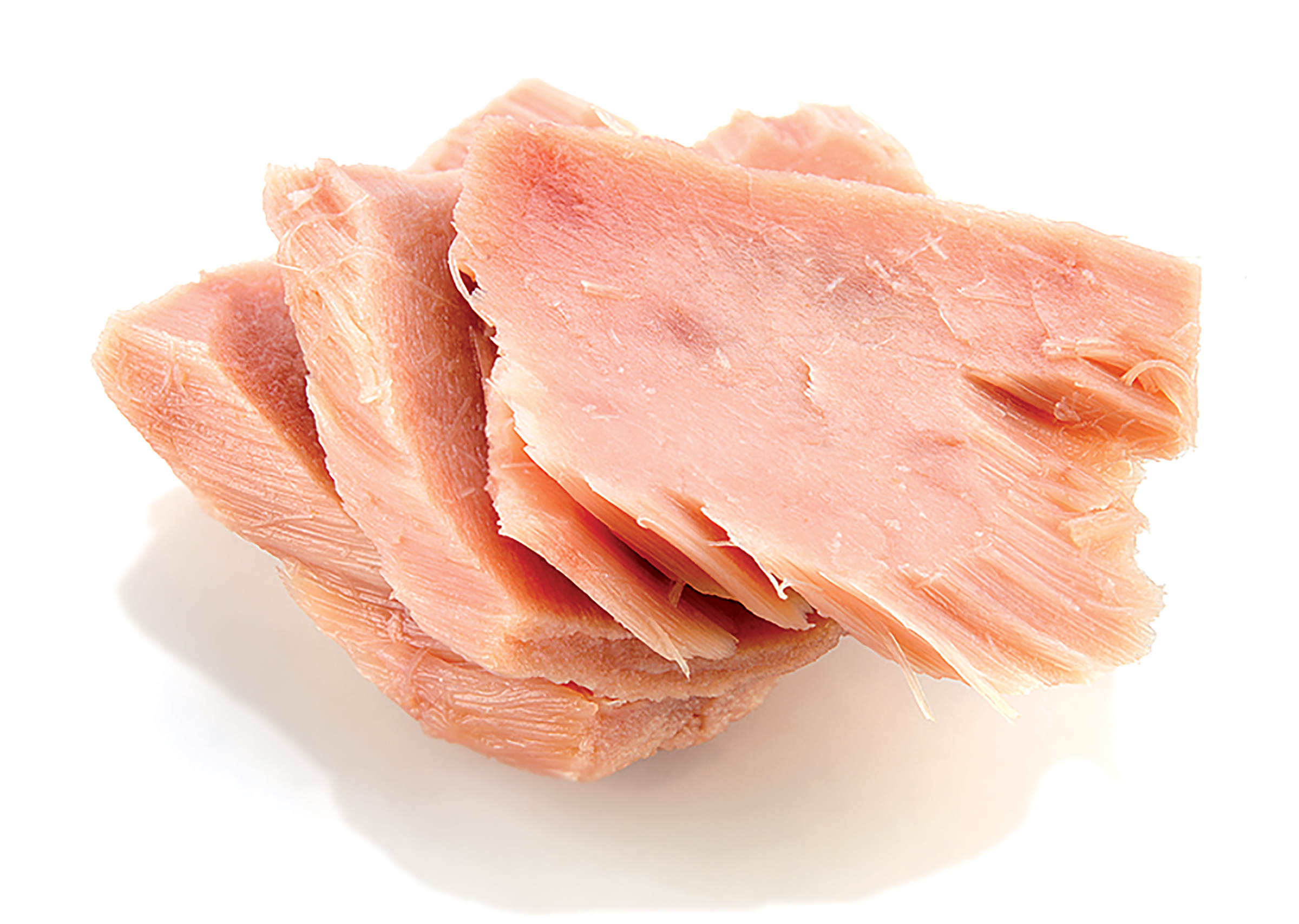

Tuna

“Yellowfin tuna is high in selenium, which is an essential trace element that plays a role in hair-follicle development,” says Merletti. But she reiterates that too much selenium can also cause hair loss, so if you’re not deficient, don’t supplement.

Fritos

“Corn chips such as Fritos are high in omega-6 fatty acids, which may promote hair growth by enhancing follicle proliferation. Of course, there are more nutrient-dense sources, including sunflower seeds, pine nuts, and soybean oil.”

This article appears in the June 2019 issue of Washingtonian.