Matt McCormick, a real-estate agent with TTR Sotheby’s, specializes in upscale Washington-area residential properties. As such, he’s had a lot of experience with people like Dimitri and Paula. “Baby boomers all wanted the same thing,” says McCormick. “Sell their big home for $2 million or $3 million, buy a big DC condominium for $1 million—overlooking the Potomac, of course, wraparound terrace, walking distance of good restaurants—and pocket the difference.”

The couple had moved their growing family into a particularly affluent corner of suburbia in the early 2000s. But now, with empty-nesterhood in sight, they’re pulling up stakes for a condo. It’s a pretty standard generational tale, buying a big house on a green patch when the kids are underfoot, then trading down and making a profit when they leave home.

But in 2019, it’s more complicated. Cashing in on their life’s investment is no longer so easy. Dimitri has been spending the last year making significant investments in the high-end home he plans to leave. He plans to install a wine cellar. There’s a new game room in the basement. He got a quieter dishwasher to go under the upgraded kitchen countertops.

Dimitri—who doesn’t want to use his real name because he’s still trying to unload his house—calls the investments “defensive,” and the data suggests he’s wise to make them. “I want to be a bride, not a bridesmaid,” he says. “Over the last few months, the price per square foot has been dropping here. Every six months we stay, the more erosion in value we’ll see.” The wine cellar isn’t meant to add value to the home—it’s meant to shore it up.

“Five years ago, boomers in suburbia were thinking the urban stuff was just far too overvalued,” McCormick says. “But now those customers have recognized that their properties just aren’t going to rise in price relative to the walkable urban properties.”

Walkable urban properties are all that Beth, a single 32-year-old manager at a nanotechnology company, ever considered. Having moved to DC five years ago with a degree in environmental design, she recently found a one-bedroom place near Meridian Hill Park.

“It meets probably 70 percent of my original search criteria,” she says of her new place. But it fully meets her most foundational one. For Beth, walkability means liberation from car dependence, connections to friends, and more opportunities to meet a potential partner in the context of a demanding professional life.

Again, it seems like a classic generational tale: the single person stretching financially to live somewhere that enables social connections.

Yet it’s Beth who sounds downright strategic in her thinking, designed to maximize future appreciation. “I was looking for something on the Yellow and Green lines in anticipation of Amazon coming to town,” she says. While she may one day sell or rent her new condo, urban living is a long-term goal. “I will always live in the District if I can. Walkability and city life are huge for me.”

Dimitri and Paula’s and Beth’s situations—along with those of so many others in the “favored quarter,” the real-estate scholar’s term for the 90-degree arc of a region, extending from upscale portions of the central city to the priciest regions of the suburbs—represents a major change in conventional thinking about the real-estate market. (In the Washington area, the favored quarter lies to the northwest on both sides of the Potomac.) But it also tells a generational story, one that scrambles some of the conventional thinking that says baby boomers can expect to live large over the next few decades while millennials face grim economic odds.

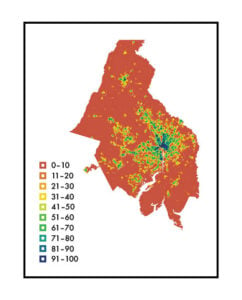

The region’s walk score. Here’s the basic pattern that local agents and national real-estate scholars have noticed: The car-dependent suburbs that, for most of the baby-boom generation’s lives, have represented success for much of America’s middle class are losing value relative to the denser sorts of neighborhoods the bourgeoisie once fled. Some of those more packed neighborhoods are central-city; others are beyond the city limits, places such as downtown Bethesda, parts of Arlington, and Reston Town Center that have been reinvented as the sort of downtowns their suburban homeowners once resisted.

The effects of this phenomenon are already apparent. Arthur C. Nelson, a professor of planning and real-estate development at the University of Arizona, notes that many boomers are holding onto their houses longer than is historically typical—with average tenures up from six years to between nine and ten—largely because their house prices still haven’t recovered from the 2008–09 recession. (The Case-Shiller Home Price Index shows the Washington area had climbed by January 2019 to around 90.5 percent of its real-dollar term high in March 2006.) House prices in drivable suburban areas have grown particularly sluggishly.

Ironically for the richest generation in American history, many boomers have found themselves trapped in larger fringe properties originally prized for their apartness. WalkScore.com has found that homes in car-dependent suburbs spend more time on the market. From January 2018 to January 2019, homes in Arlington, with its seven “WalkUPs” (Walkable Urban Places) and “somewhat walkable” Walk Score of 69 (out of 100), averaged 61 days active on Zillow. The District of Columbia proper (Walk Score: 77) averaged a similar 64 days. In contrast, car-dependent McLean (Walk Score: 23) and Bethesda (Walk Score: 46) averaged 79 and 85 days, respectively. Farther out, wealthy, drivable Potomac (Walk Score: 16) averaged 97.5 days.

Drivable suburbia is also aging. Between 2000 and 2016, the percentage of homeowners in Washington’s inner suburbs who were between ages 52 and 70 rose from 32 percent to 41 percent. Moreover, area boomers have tended to own houses that are larger than their current needs: More than one-quarter of homeowners over age 50 have two or more extra bedrooms.

Ordinarily, the market would offer a fix: The oldsters trade down to something smaller, the next generation trades up to something that can fit their growing families, and everyone lives happily ever after.

The problem is that buyers under 40, thus far, have proven less eager to fulfill their end of the bargain. Part of the problem is they’re less likely to buy anything: At 37 percent, the rate of homeownership for today’s 25-to-34-year-olds is 8 points lower than it was for Gen-Xers and boomers when they were the same age—this despite a higher median household income than previous generations. The reasons are varied, including student-debt burdens, delayed marriage, and greater ethnic diversity (people of color are less likely to own their own home and more likely to face barriers to the housing and credit markets).

But another problem is very basic: Millennials are less likely to want what’s for sale. The discrepancy between these generations’ relationships to the urban fabric in their respective early homebuying years is stark. More millennials—about one-third—have preferred residing in denser, walkable urban environments. The preference is strongest among the highly educated, who find better salaries in knowledge industries that tend to locate in expensive walkable urban places.

To be sure, the phenomenon we’ve been studying involves comparatively affluent residents who have the luxury of choices unavailable to many citizens. But the decisions of elites like these often have long-term consequences for society at large.

One weird side effect of this pattern: intergenerational bidding wars.

“We no longer have different demographics of buyers looking for different markets and product types,” McCormick says. “They’ve now all converged and are basically looking for the same thing. Young kids are competing against empty-nesters. Young people are losing out on bids from folks their parents’ age.” Demand far outstrips supply. So, bucking the national trend, bidding wars in some DC neighborhoods have heated up, with desirable walkable properties now routinely getting ten-plus bids and winning offers often coming in well over the asking price, in cash and with no contingencies. Millennials are often simply outgunned.

“For the younger buyers, I’ll write nine, ten, 13 contracts,” says McCormick. “They lose out again and again.”

But in already-walkable enclaves like that, everyone agrees about what sort of neighborhood it is. Elsewhere, notably in inner-ring suburbs such as Takoma Park and Vienna, there’s been a generational tilt to face-offs over what type of neighborhoods they should become—should they stay as is or develop into a downtown along the lines of central Bethesda or the mini-downtowns in Arlington? Even within existing walkable urban areas, divides have emerged over questions such as densification, height limits, zoning, and inclusiveness. Raising zoning-density limits has been a major bone of contention in Reston, for instance, where longtime residents have resisted densification. The third of Bethesda’s three master-planning efforts in the last half century, launched in 2017, saw a bruising battle over densification and associated issues such as school overcrowding, traffic congestion, and the fate of single-family housing stock.

If the question were just about which type of setup led to higher property values, the answer would be quite clear, as would the generational import.

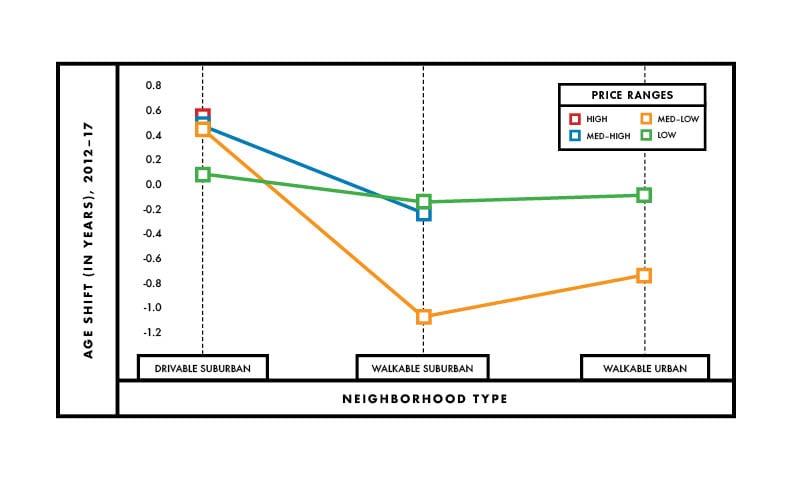

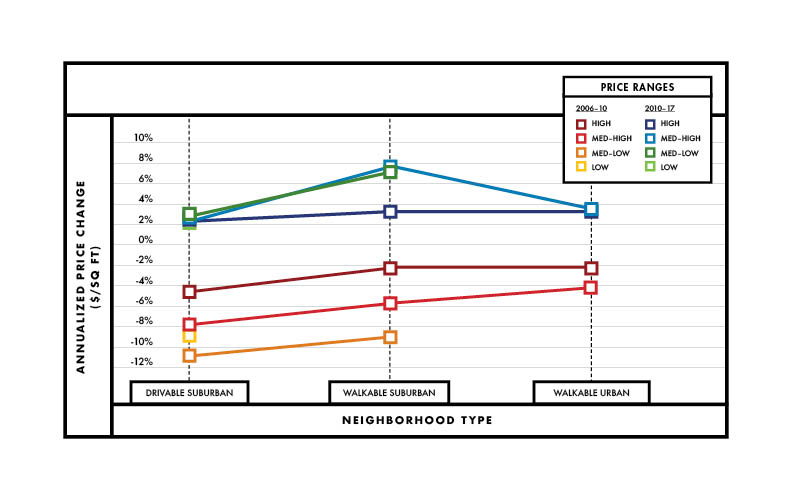

Across nearly all prices, the more walkable parts of the region (map, right) are getting younger (below, top) and tend to better retain their value (below, bottom). The average age in car-dependent suburbs is up—an indication of a new generational tilt.

We examined 211 Washington-area Zip codes linking walkability to changes in age and market price, using dollars per square foot. In particular, we wanted to understand how walkability affected the home values during two periods: first during the most recent recession (from the market peak in May 2006 to its nadir in October 2010) and second during the recovery and subsequent expansion (October 2010 to January 2019).

Maps of these phenomena are revelatory. The most walkable areas have tended to remain age-stable or to grow younger: Zip codes with Walk Scores of around 75 have gotten younger by 0.2 year on average. Conversely, the least walkable areas have tended to grow older: Zips with Walk Scores of 20 have aged by 0.65 year on average. Most important, the most walkable areas suffered much less severe price declines during the last housing-price recession than the drivable suburbs: Zip codes with Walk Scores of 80 to 100 dropped by just 0 percent to 2.5 percent a year on average, while those in the 0-to-20 Walk Score range declined by about 8 percent a year. Moreover, walkable areas have generally benefited more from higher appreciation rates during the post-recession expansion than has drivable suburbia, with yearly appreciation rates of around 4 percent, compared with drivable suburbia’s 2 percent.

The market has been responding even outside the favored quarter, particularly in eastern Montgomery and Prince George’s counties, by building walkable urban areas in Silver Spring, Takoma Park, and National Harbor, among other places, as well as in the District’s Brookland and Anacostia. Walkable, high-end suburban locales outside the favored quarter have gained value at more than 2.5 times the rate of similar places within it. This movement speaks to gentrification but also to the artificial scarcity—i.e., zoning codes that make it harder to build dense, city-style real estate—that causes it.

Will these trends change? It doesn’t look likely, at least in dollars and cents. In the past, public-school quality has been a major housing-decision factor for families with children, making them gravitate to drivable suburbs. However, the improvement in DC public-school options and the fact that only 13.5 percent of the future growth in households is composed of parents with school-age children in the home (singles and two-person households make up the rest) mitigate this factor.

Meanwhile, a glut of boomer-owned housing stock anticipated to be dumped on the market in the mid-to-late 2020s—estimated at 13 million to 14.6 million units, or a 42-percent increase over the volume seen in the past decade—will only further depress prices. The short supply of walkable urban housing would likely help the more built-up areas weather a recession. While some developers, such as EYA (tagline: “Life within walking distance”) are working to fill the walkable-housing supply gap, their efforts aren’t likely to be enough to meet demand.

And of course, low supply implies that walkable-housing prices will continue to rise relative to drivable suburbia over the next decade.

In fact, buried in this trend is a way that suburbia could yet be the millennials’ future—just not how people such as Dimitri might prefer. Yes, younger homeowners have proven willing to pay a premium to live in walkable areas. But how much of one? If the trends of the last few years continue—that is, if affluent suburbs continue to see prices lose ground relative to walkable urban places—we may yet find out.

Of course, the question now is: What should the Washington region do before the current trends snowball? Our advice: Those in drivable suburbia who can (and want to) would do well to sell soon. Those who don’t move might usefully help convert their neighborhoods into more walkable areas—NIMBYism against densification will contribute to housing-price declines.

By contrast, helping to supply the walkable urbanism the Washington market wants will enable these homeowners eventually to benefit from a “halo effect,” whereby substantial rises in home prices occur in the walkable ring surrounding high-density walkable urban environments. These single-family neighbors within walking distance of great walkable urbanism will have the best of both worlds, increasing their home values by 20 to 60 percent per square foot compared with similar homes outside of walking distance.

There lies the intergenerational compromise that many boomers and millennials will have to make: The millennials bring their families to the suburbs, and the boomers enable them to make the suburbs more walkable, vibrant, and, yes, desirable.

Median gross DC rent when they came of age:

Silent Generation

$346 (1950)

Baby boomers

$457 (1970)

Generation X

$612 (1990)

Millennials

$1,011 (2010)

This article appears in the July 2019 issue of Washingtonian.