What makes a restaurant important? It could be food that doesn’t just push the limits but blasts through them. It could be a space where a community is created and comes together. Maybe it’s a new-to-Washington cuisine that goes on to root and blossom, or a chef who forever changes the way we perceive food. Let’s take a look back, starting with a time long before small plates and $14 salads. These are the 50 most significant Washington restaurants of the last century.

*How many have you been to? Start filling out your checklist in the blue box above.

Hot Shoppes (1927–1999)

Multiple area locations

Fast food wasn’t much of a thing in the early 1900s. McDonald’s and Wendy’s were decades away. But here, we had Hot Shoppes, the chain of orange-roofed restaurants that Bill and Alice Marriott launched long before they opened their first hotel. What started as a tiny counter in Columbia Heights grew into a 70-location brand, famous for Teen Twist sandwiches and double cheeseburgers.

Sholls Cafeteria (1928–2001)

Multiple DC and Virginia locations

Think the lines at Sweetgreen are bad? You never saw the ones at these lunchtime cafeterias across the District and Virginia. Students and retirees, Presidents and postal workers, Black people and white people crammed in for self-serve liver and onions and cherry pie. But as office-lunch options got even cheaper and more casual in the ’80s and ’90s, the lines shrank. The last of eight Sholls locations closed after 9/11.

Southern Dining Room (1938–1980s)

1616 Seventh St., NW

Soul food became a nationwide craze in midcentury, and this Shaw cafeteria evolved into one of the country’s top places to get it. The reason: chef Hettie Gross, who cooked the chitterlings and cornbread she’d grown up on in Alabama.

Crisfield (1945–present)

8012 Georgia Ave., Silver Spring

This seafood spot, with its horseshoe bar and collection of antique oyster plates, feels fixed in time. It conjures the days when Maryland crabs were bountiful (founder Lillian Landis was famed for her crab imperial) and is a reminder of how closely Washington’s culinary identity was once tied to the Chesapeake Bay.

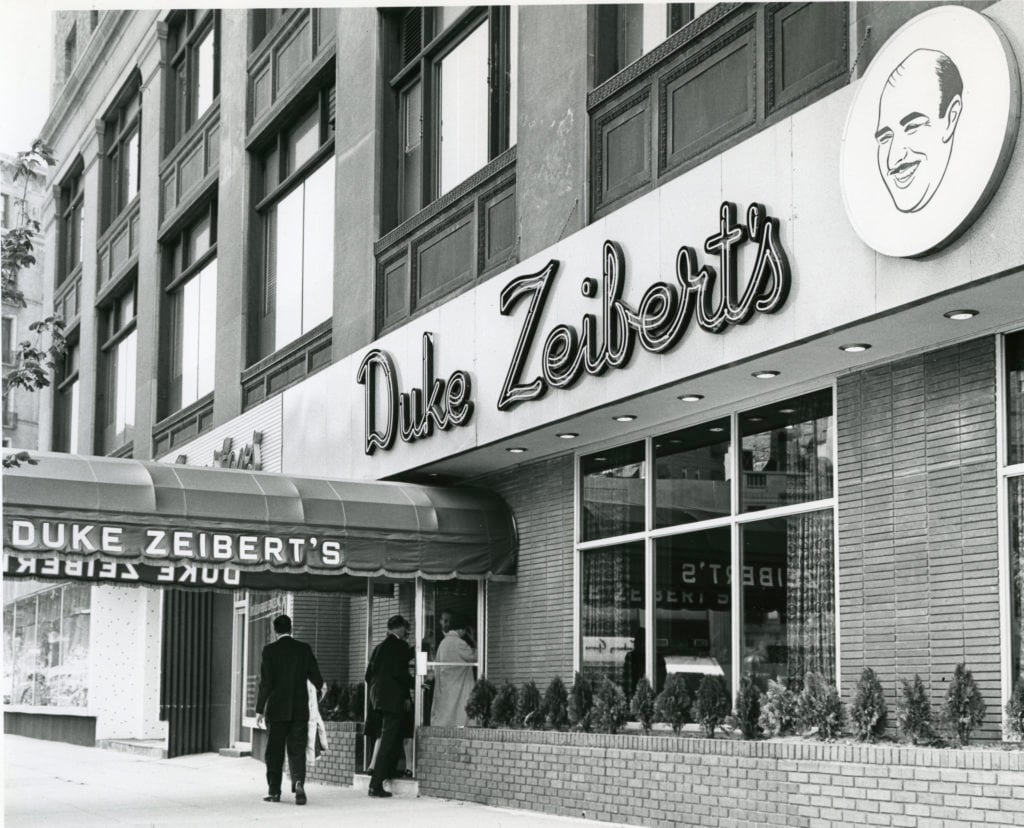

Duke Zeibert’s (1950–1980, 1983–1994)

1730 L St., NW; 1120 Connecticut Ave., NW

Few restaurant figures loom as large in Washington history as Duke Zeibert, the zinger-slinging owner of one of the city’s most enduring power hubs. Whether you were a quarterback, a movie star, or a nobody, your power rank would be reflected in the table he selected for you. The food, American comfort fare with a dash of Jewish deli, never eclipsed the guy behind it.

Thompson’s Restaurant (1950s)

725 14th St., NW

A restaurant more significant for what it didn’t do than what it did. In 1950, African American civil-rights leader Mary Church Terrell arrived at this chain cafeteria for lunch—and, at 86 years old, was refused service. The activist knew what she was doing. Aware that a set of little-known antidiscrimination laws from the late 19th century had been long ignored, she used the experience to push the city to sue the restaurant. The Supreme Court ruled in DC’s favor, making discrimination at restaurants and other establishments illegal.

Yenching Palace (1955–2007)

3524 Connecticut Ave., NW

When it comes to DC dining lore, Yenching Palace has one of the most famous stories: that representatives from the US and Soviet Union resolved the Cuban Missile Crisis here in a back booth. But Yenching was more than that—one of DC’s first upscale Chinese dining rooms, both a neighborhood fixture and a glam scene.

Billy Simpson’s House of Seafood and Steaks (1956–1978)

3815 Georgia Ave., NW

In post-segregation Washington, this high-end restaurant became the unofficial dining room and intellectual clubhouse for the city’s Black elite. Owner Billy Simpson—who also went by “the mayor of Georgia Avenue”—was known as much for his roundtable civil-rights and political debates as he was for his shrimp and steak.

Rive Gauche (1956–1997)

1310 Wisconsin Ave., NW

For decades, Washington’s fancy restaurants were French. And this Georgetown dining room was the fanciest, Frenchest of them all. Crazy expensive and hard to get into, it set the standard for special-occasion dining in the era when butter and cream ruled.

Ben’s Chili Bowl (1958–present)

1213 U St., NW (other location at 1001 H St., NE)

Is there a restaurant more closely associated with DC than Ben and Virginia Ali’s late-night hangout? Its history is legendary—the star of the so-called black Broadway, it survived not only the Molotov cocktails of the 1968 riots but also potentially ruinous construction obstacles and, thus far, a pandemic. And while Washington doesn’t have much in the way of regional claim-to-fame foods, the half-smoke, most notably served at Ben’s, is up there.

The Jockey Club (1961–2001, 2008–2011)

2100 Massachusetts Ave., NW

Before Fiola Mare, before Cafe Milano, there was the Jockey Club—one of DC’s first see-and-be-seen places for both White House and Hollywood crowds. Jackie Kennedy dined there with Marlon Brando early on, and Nancy Reagan became a salad-picking regular. Toward the end, as Washington’s food scene heated up, the place felt like a relic. It reopened tepidly in 2008 and finally sputtered out in 2011.

Clyde’s of Georgetown (1963–present)

3236 M St., NW (several other area locations)

Washington’s first true restaurant/bar hybrid. In the early ’60s, banker turned restaurateur Stuart Davidson put a freshly changed law into play: His was the first DC restaurant to serve hard liquor to customers standing at a bar (not just seated in the dining room). It was also one of the first spots—love it or hate it for this—to popularize Sunday brunch.

Sans Souci (1963–1983)

726 17th St., NW

DC doesn’t have much of a power-lunch culture anymore. But it sure used to. And this swank, Camelot-era French dining room near the White House, with its green banquettes and vichyssoise, was the spot that made 12 pm reservations trendy. Much of that was due to the star of the show: affable but protective maître d’ Paul Delisle, who cultivated a roster of boldface politician and journalist regulars.

Cantina d’Italia (1968–1988)

1214 Connecticut Ave., NW

There was plenty of Italian cuisine in Washington when this snug basement restaurant opened—but this was the first that took a fine-dining approach. Also setting it apart: The cooking was Northern Italian—a style that would later influence many of DC’s expense-account spots.

Mamma Desta (1978–1983)

4840 Georgia Ave., NW

Doro wat, the berbere-red chicken stew, is now one of our food scene’s biggest draws, but in the mid-’70s—as many Ethiopians were fleeing their country’s civil war and landing in neighborhoods like Adams Morgan—you could find it at only one place: Mamma Desta. The city’s first Ethiopian restaurant may not be as famous or long-lasting as institutions like Meskerem or Dukem, but chef Desta Bairu (who was actually Eritrean) effectively introduced Washington to one of its most important cuisines.

Sushiko (1976–present)

2309 Wisconsin Ave., NW (original location); 5455 Wisconsin Ave., Chevy Chase (current location)

Before this Glover Park restaurant opened, Japanese dining in this town mostly meant tempura and Benihana-style hibachi. DC’s first sushi restaurant—it has since relocated to Chevy Chase—nudged diners into the world of raw fish.

The Inn at Little Washington (1978–present)

309 Middle St., Washington, Va.

“Playful” is not how you’d have described any of Washington’s celebratory restaurants—until Reinhardt Lynch and Patrick O’Connell came along. They turned a dilapidated garage in a tiny Rappahannock County town into one of the country’s great dining destinations—enduringly famous for winking dishes such as “tuna pretending to be filet mignon.” Eventually, the Inn’s staff outnumbered the population.

Jean-Louis (1979–1996)

2650 Virginia Ave., NW

One of the things you notice reading pre-1990s restaurant reviews is how seldom chefs are mentioned by name. Jean-Louis Palladin changed that. The bad-boy Frenchman with the cascading curls and thick ’stache was DC’s first celebrity in whites. At his Watergate dining room, he disrupted French cuisine with meticulously sourced American ingredients and relentless creativity.

Restaurant Nora (1979–2017)

2132 Florida Ave., NW

Forty years ago, the high-end dining scene here was ruled by chefs who were (a) French and (b) male. Nora Pouillon elbowed her way onto the stage with a Dupont Circle restaurant that focused more on ingredients and the farmers behind them than on showy knife work or intricate technique. The reason servers and menus often name-check growers? The movement stemmed from this all-organic kitchen.

El Tamarindo (1982–present)

1785 Florida Ave., NW

A three-decades-and-running Adams Morgan institution that’s emblematic of what many Salvadorans did when they moved here and opened restaurants: offered their cuisine alongside Mexican dishes, with the logic that tacos would be more recognizable to consumers than pupusas.

Galileo (1984–2006)

1110 21st St., NW

In the early ’80s, there was no shortage of places for a high-dollar bowl of risotto. Twenty-three-year-old chef Roberto Donna blew past the competition when he opened this downtown dining room, which blended Old World rusticity with an elegant touch—and luxuries like Alba truffles. Also forward-thinking: Laboratorio del Galileo, his restaurant-inside-a-restaurant with an extra-long tasting menu and a showpiece kitchen.

Carlyle (1986–present)

4000 Campbell Ave., Arlington

From the get-go, the family-run Great American Restaurants group devoted itself to improving the Northern Virginia dining landscape. Its crown jewel in Shirlington mixes a swank dining room with a menu that has the focus-grouped approachability of a chain (but a good one!). It’s become an often-imitated template.

Duangrat’s (1987–present)

5878 Leesburg Pike, Falls Church

This Baileys Crossroads dining room was one of the first restaurants in the suburbs to offer an affordable menu and a date-night atmosphere (servers in silk dresses, a Trumpian amount of gilt). It went beyond Americanized Thai staples, and its success helped spur the Thai-restaurant boom in the 1990s.

Marvelous Market (1990–2014)

5035 Connecticut Ave., NW

Picture this. You sit down to an expensive dinner with otherwise excellent food, and you’re served . . . dinner rolls. Out of a package. Bread in Washington was an afterthought until Mark Furstenberg upped the city’s baking game with this Forest Hills bakery. Lines for a black-olive loaf or boule snaked through the place, which he spun off into other locations and then sold in 1996.

Horace and Dickie’s (1990–2020)

809 12th St., NE (other locations in Takoma, Glenarden, Suitland, and Waldorf)

DC’s carryout culture has always been strong, and this squat joint became the most famous. It specialized in one thing: cornmeal-battered fried-whiting sandwiches, dashed with hot sauce and served on white bread. As the H Street corridor gentrified, condo buildings and wine bars moved in—and a piece of local history got pushed out.

Pizzeria Paradiso (1991–present)

2003 P St., NW (other locations in Georgetown, Spring Valley, and Hyattsville)

Washington’s pizza identity is finally evolving, but if anything defined it over the last 25 years, it was the supremacy of the Neapolitan pie. Basil-strewn Margheritas weren’t the only pizzas here, but in many cases they were the only ones worth making a special trip for. It all started with Ruth Gresser, who brought the style—with its strict rules and imported ingredients—to her tiny pizzeria in Dupont Circle.

Red Sage (1991–2006)

605 14th St., NW

Washington restaurants weren’t exactly known for their flashiness, so when Santa Fe chef Marc Miller shelled out $6 million to decorate his haute-Southwestern dining room, lots of people (including the new-to-town Clintons) took notice. Restaurateurs realized the importance of—and started getting creative with—decor.

Citronelle (1993–2012)

3000 M St., NW

The late Michel Richard was a Frenchman who loved America—and American junk food. At his Georgetown flagship, the impishly brilliant chef used a Kit-Kat bar as inspiration for a four-star dessert, fashioned burgers out of lobster, and reveled in fooling guests with trompe l’oeil tricks (it’s not a rubber duck, it’s meringue!). Underpinning it all: meticulous French technique. Richard was one of the most exciting culinary minds this city—and this country—has ever seen.

Huong Que/Four Sisters (1993–present)

6769 Wilson Blvd., Falls Church (original location); 8190 Strawberry Ln., Falls Church (current location)

The Lai family’s Vietnamese restaurant wasn’t the first in the Eden Center, the microcosm of Vietnamese restaurants and shops that opened in 1984. But for nearly two decades, it was the most talked-about. The secret: a gracious, art-filled dining room and a menu that appealed to both natives and Westerners. It was Inn at Little Washington owner Patrick O’Connell, an early fan, who dubbed the restaurant “Four Sisters.” When it moved to the Mosaic district, the Lais made the name change official.

Jaleo (1993–present)

480 Seventh St., NW (other locations in Bethesda and Crystal City)

These days, everything from mapo tofu to a bacon cheeseburger is available in small-plate form. But 30 years ago, sharing a bunch of little dishes was a seismic departure from the mealtime norm, at least in America. Credit goes to José Andrés, who first popularized Spanish snacks at his original Penn Quarter tapas house, then devoted more restaurants to shrinking down dishes from other cuisines.

Kinkead’s (1993–2012)

2000 Pennsylvania Ave., NW

Lest you think of the late Bob Kinkead’s flagship dining room as part of the DC old guard, let us remind you of something: He was serving poke in the ’90s. Kinkead was a seafood obsessive, but a forward-thinking one. It was his championing of lesser-known fish, and his masterful wielding of international flavors, that made him both a pioneer and a chef to remember.

Vidalia (1993–2016)

1990 M St., NW

Jeff Buben’s Southern dining room in a downtown basement was for years one of DC’s top restaurants, melding cheffy shrimp and grits with fancy wine and high-toned service. But it should also be remembered as one of our great talent incubators. Alumni include Eric Ziebold (Kinship/Métier), Tom Cunanan (formerly of Bad Saint), and Cathal Armstrong (Restaurant Eve, Kaliwa).

Palena/Palena Cafe (2001–2014)

3529 Connecticut Ave., NW

Is Frank Ruta the reason your burger now costs 18 bucks? It’s not all on him, but his truffle-cheese-topped patty on a brioche-like housemade bun was the most famous of the first wave of fancy burgers. And while it’s now common to see what are essentially two restaurants operating under a single roof—one with a casual bar menu, the other with loftier ambitions—Ruta was among the first to pull it off in DC, at this Cleveland Park dining room/cafe.

Ray’s the Steaks (2002–2019)

1725 Wilson Blvd., Arlington

There are some restaurants that double as cultural touchstones—simply knowing of their existence ups your food-wonk clout—and this strip-mall steakhouse was just that. Eventually, word got out beyond internet forums that Michael Landrum’s place was revolutionary: value-driven, bare-bones, and suburban, but with a top-notch wine list and cuts of beef that rivaled what you’d find at the expense-account places.

Minibar (2003–present)

855 E St., NW (original location); 405 Eighth St., NW (current location)

There was some question, 17 years ago, of whether Washington would support a restaurant that offered a 20-course menu of things like clam chowder distilled into gelatinous dabs on a plate. But José Andrés’s modernist project flourished, moving from a six-seat bar inside Café Atlántico to its own space nearby. It became the area’s most expensive restaurant—and kick-started the rise of tasting-menu restaurants (and checks) across the city.

Etete (2004–2018)

1942 Ninth St., NW

The star of Shaw’s Little Ethiopia neighborhood for many years—and the first Ethio restaurant here with a modern, bistro-like vibe. Even better: Tiwaltengus Shengelegne’s tibs and kitfo were punchy and vivid and never capitulated to anyone else’s palate.

Restaurant Eve (2004–2018)

110 S. Pitt St., Alexandria

Old Town was one of the area’s more staid dining neighborhoods—until Cathal and Meshelle Armstrong’s hybrid bar/cocktail destination/bistro/tasting room came along. The jewel-toned place was obsessively locavore and endlessly fun (remember the mini pink-frosted birthday-cake dessert?), and its familiar servers helped make fine dining a whole lot less stuffy.

Busboys and Poets (2005–present)

Multiple area locations

Activist/restaurateur Andy Shallal opened the first of his veggie-friendly restaurant/bookstore/gathering spaces at 14th and V. He’s expanded to several developing neighborhoods and is one of the area’s only restaurateurs to expand across the Anacostia River.

Rasika (2005–present)

633 D St., NW; 1190 New Hampshire Ave., NW

Ashok Bajaj had long been masterminding a certain type of restaurant that excelled in DC: interesting but not boundary-pushing, subdued but not boring. In other words, not places the food-obsessed would seek out. Until this national-class Indian dining room, which pushed curries and chaats in thrilling new directions.

Sweetgreen (2007–present)

3333 M St., NW (original location; multiple other locations)

When three recent Georgetown grads took over a former Little Tavern hut near the university, a salad behemoth was born. Its timing was perfect: The wellness brigade had pegged gluten and dairy as dietary enemies, and as the chain expanded through the nation, Instagram culture—with its love for all things colorful in a bowl—was taking off. Goodbye, shrink-wrapped turkey sandwich; hello, $11 Guacamole Greens salad.

Honey Pig (2008–present)

7220 Columbia Pike, Annandale (other locations in Ellicott City, Rockville, Germantown, and Centreville)

The 1970s brought waves of Korean immigrants to Annandale, and soon after, soup shops, buffets, and noodle joints started popping up. But none has ever been quite as buzzy as Annandale’s rap-blaring, smoke-filled barbecue house, which offers both top-notch bulgogi and a taste of Seoul’s soju-drenched after-hours scene.

Cork (2008–present)

1720 14th St., NW (original location); 1805 14th St., NW (current location)

There had long been idiosyncratic, ambitious wine bars all over cities like San Francisco and New York, but here, Cork was the first—and one of the early draws to new-wave 14th Street. Its approachable, sharing-friendly menu (cheffy grilled cheeses, avocado toast long before avocado toast was a thing) once commanded two-hour waits .

Bangkok Golden/Padaek (2010–present)

6395 Seven Corners Center, Falls Church

Those fiery, sour flavors that have ruled the Southeast Asian dining scene here over the last ten years? Their influence can be traced to Seng Luangrath, who, with a secret menu at her strip-mall Thai restaurant, introduced Washington to spiky, potent Laotian cooking. Suddenly, chili-chasing became sport, and Lao and Northern Thai restaurants multi-plied accordingly.

Graffiato (2011–2018)

707 Sixth St., NW

Yes, we know. But the trajectory of Mike Isabella—from José Andrés protégé to Top Chef star to Washington’s biggest restaurateur—wasn’t nearly as swift as the #MeToo-fueled burn-down of his $12-million empire. With this first restaurant, the brash dude with the pepperoni sauce ushered in a reign of share-plate-slinging bro-chefs who were always up for a shot—whether a fan photo or a hit of tequila.

Toki Underground (2011–present)

1234 H St., NE

With its Wu Tang soundtrack, comfort-resistant stools, and relentlessly porky ramen, Erik Bruner-Yang’s 28-seater was one of the first H Street dining destinations. Its sensibility owes a debt to David Chang’s Momofuku, but here it was the start of the hipster-Asian restaurant trend.

Rappahannock Oyster Bar (2012–present)

1309 Fifth St., NE (other location at 1150 Maine Ave., SW)

First, cousins Travis and Ryan Croxton resurrected the Chesapeake Bay oyster industry. Then they opened this spare raw bar—both an excellent place to eat and drink and the centerpiece of Union Market, DC’s groundbreaking food hall.

Rose’s Luxury (2013–present)

717 Eighth St., SE

Aaron Silverman’s rowhouse restaurant—with its endless line out the door and a pantry that pings all over the globe—is what finally caused DC’s collective dining-conscious to lose the chip on its shoulder. We always knew we were way more than a steakhouse town, but when Rose’s became the darling of the nation-al media, our food scene finally got a little respect.

The Dabney (2015–present)

122 Blagden Alley, NW

Jeremiah Langhorne—who learned the ropes under chef Sean Brock in Charleston—is both a devoted historian and a fanatical locavore who has dedicated himself to protecting our regional traditions. Sugar toads, pawpaws, porgy, and all manner of other forgotten Mid-Atlantic delicacies are revived and modernized at his hearth-driven Shaw kitchen.

Bad Saint (2015–present)

3226 11th St., NW

Tiny, idiosyncratic, and devoted to deep-diving into a little-seen cuisine in Washington (Filipino), this Columbia Heights dining room is the kind of place that can exist only in a thrumming food city—one that’s filled with engaged, curious eaters willing to shiver in line for more than an hour to taste former chef Tom Cunanan’s electrifyingly good sisig and bitter melon.

Kith and Kin (2017–present)

801 Wharf St., SW

Walk through the Wharf after a show at the Anthem started, and you’d find one restaurant that was packed night after night: Kwame Onwuachi’s ode to Afro-Caribbean flavors. Onwuachi left in July, but his influence is far-reaching: The 30-year-old chef has been instrumental in making kitchen culture more diverse and humane.