Natasha Cloud finds the video, lowers the volume, and hands you her phone. It’s a racist screed on Snapchat, yapped in a school cafeteria by a teenage girl who is white. It’s vile, pure filth—made even more disturbing because the girl is sitting next to a Black classmate. About the fifth N-word in, you hand the phone back to the 29-year-old point guard of the Washington Mystics.

“We had to handle it,” Cloud begins.

Handle it?

“We couldn’t let it go.”

Cloud and her wife, professional softball player Aleshia Ocasio, researched the girl and discovered that her mother runs a gym owned by a good friend. The friend was verklempt, apologizing to them both over the phone, swearing that the mother “doesn’t have a bigoted bone in her body.” Cloud and Ocasio told her they understood but the woman needed to confront her daughter—have a hard conversation about race. Cloud reminded their friend that she and her wife worked out at her facility. “If you don’t handle it,” she said, “then we can’t come and associate ourselves with your company.”

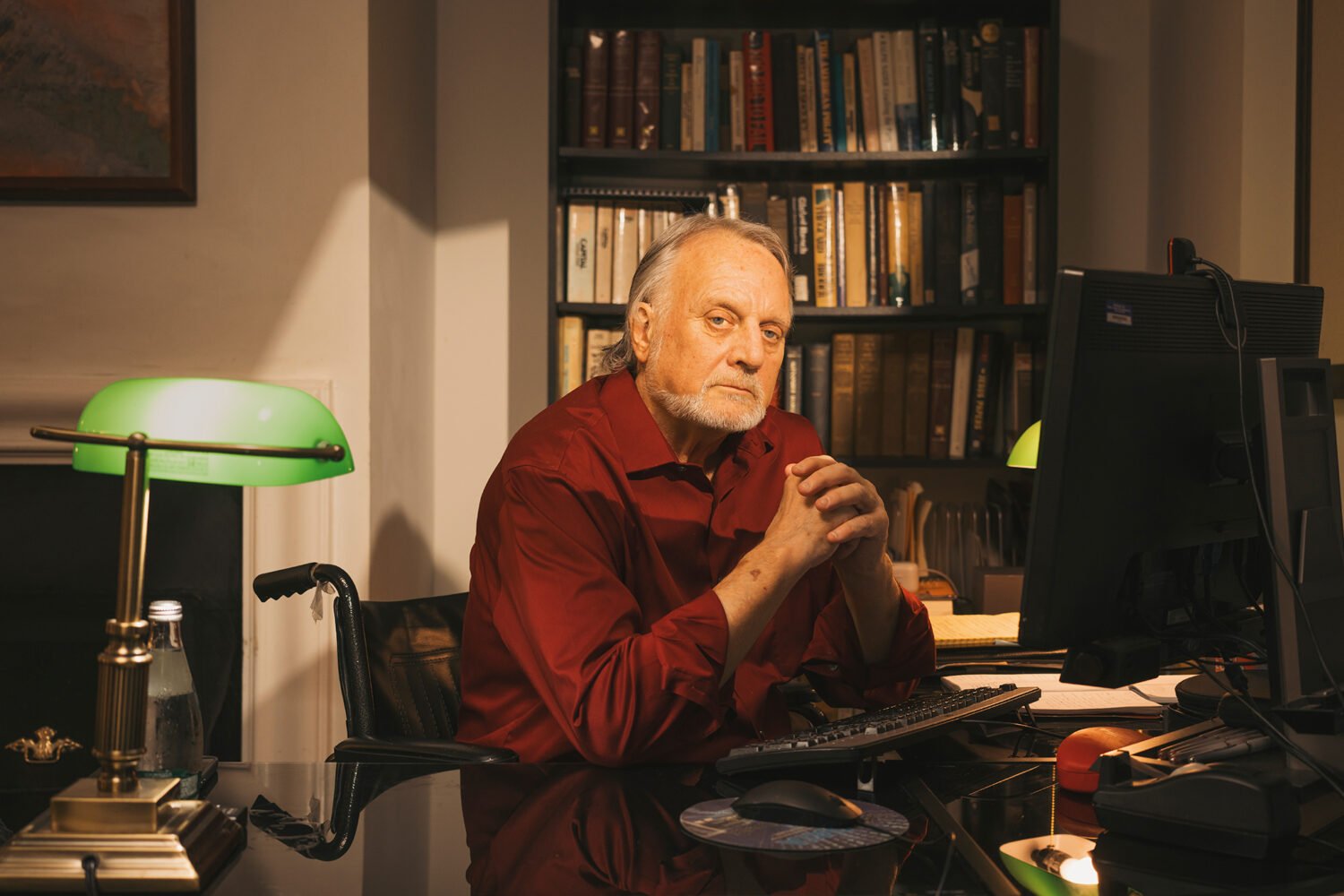

You may never have watched Number 9 for the Mystics, seen her launch that three-point bomb with aplomb or skitter past defenders as if they were orange traffic pylons on her way toward an open teammate. But it’s a good bet you still know the six-foot-tall heart of the team, who briefly played for the Terps. She’s among the new faces of Converse shoes, who seized attention in the pro sports world a year ago after the police murder of a Black man in Minneapolis, when she hung up her jersey for a whole season to work on issues of racial justice. The Mystics’ spiritual leader—“Tash” to teammates and friends—who could not just do nothing as America’s racial cauldron boiled over. An WNBA champion who’s had enough with the oblivious athlete, the uncaring fan, and the supposedly objective sportswriters, clicking their keyboards in the press rooms of arenas about to burn down around them.

“I can’t stand that shit,” she says, shaking her head. “Because when it comes down to it, while I’m a WNBA champion and a Washington Mystic, the minute I take that jersey off and get into my car . . . I’m a Black woman in America. My life could be over simply driving ten minutes to our apartment. I could be asleep in my apartment and still be killed. That’s our reality. When they say, ‘Stick to sports,’ how?

“How?”

Another Tash bonus track from 2020: She unfriended her only brother on Facebook and blocked his Twitter account and cell phone. His crime, along with that of one of her sisters and many former high-school friends? They voted for Donald Trump, which means they voted against same-sex marriage, Black Lives Matter, and every value and belief for which Cloud stands. They voted against her.

So now she demands that everyone pick a side. Choose. “You can’t be neutral anymore,” she says, surveying the crowd around us at a DC restaurant one day this spring. “You can’t be sitting here and something [bad] happens over there and you turn your head and continue eating. Nuh-uh. Not now.”

“She’s got a big heart,” says Emil Cloud, Natasha’s father.

“She’s got a big mouth,” Sharon Cloud, her mother, adds, chuckling first, then pausing.

“And I miss that big mouth.”

The Clouds reared Natasha in suburban Philadelphia—Broomall—watching her life in sports unfold in ways we’ve come to expect of pro athletes. Neighborhood boys knocking on the family’s door for Natasha to play baseball and football when she was seven. Their daughter, bangs tucked beneath helmet, the starting quarterback and linebacker on her Pop Warner team. The coach who eventually told the Clouds, “There are no NCAA scholarships for women in football.”

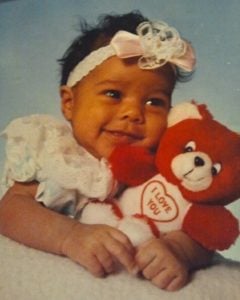

But the unexpected part of those formative years most don’t know: Natasha Cloud was a Black girl growing up with four white siblings and two white parents in a mostly white town. A kid who only began to start processing how different she was from her family and many of her peers around age 12, the day she roamed a neighborhood 7-Eleven with friends and the shopkeeper tailed her through the store.

How? Why? Natasha had tiptoed around the questions before, and Sharon had deflected. Another half dozen years went by before Sharon finally told her youngest the full truth at 18. His name, so she could reach out if she wanted. Where he lived. That he had two kids. Her mother had had an affair with a Black man during a difficult time in her marriage with Emil. The couple reconciled after Emil learned of the pregnancy.

The revelation changed nothing about Cloud’s feelings toward Emil—by then, he’d raised her for almost two decades as his own, working two jobs and trying to make his kids’ games and practices, too. Even when a relative, unbidden, presented her with documentation about her biological father’s identity a couple years ago, even though she now knew “where the gaps [in her teeth] came from,” Cloud pushed it away. “I had everything I needed. A father who loves me, who guided me through life—so there was no reason to go look for someone who didn’t want me.”

But the matter of her racial identity, that was more complicated. And for years afterward, the family—Natasha included—avoided the subject.

After high school, she accepted a scholarship to the University of Maryland and played for the Terps under Brenda Frese, the program’s legendary, hard-charging coach. “Going off to college, not having the comfort of the family around, she didn’t have her cocoon anymore,” recalls Sharon. “It was hard for her.” Cloud found herself surrounded by mostly Black women, yet feeling alone, unmoored from Black roots she’d never learned or explored, and also detached from the white culture that had defined her upbringing. Sophomore year, she transferred to St. Joseph’s University, back home in Philly.

“Seems like I was never white enough and never Black enough,” Cloud says. “The thing is, I walk outside and you see me as a Black woman. You’re not going to see that I have two white parents, all white siblings, I have a college degree. You’re just going to see my skin color and consider me a threat simply because of that.”

That revelation, the devastating matter of sociological fact that Cloud absorbed over a period of years, is the thing that has cleaved the family since she came out as an activist and the 2020 election loomed. “Yeah, [two of my] siblings voted for Trump,” she says. “We almost threw hands at each other.”

The divide opened over time during Trump’s presidency, especially with her elder brother, Eric; she finally blocked him, she says, when he kept trolling her on social media after she started speaking out. “He’d write just dumb shit, like ‘This doesn’t affect you.’ Or ‘You weren’t raised like this.’ Or ‘The media is pushing this narrative.’ ”

Eric, Sharon says, can’t understand why Natasha—the only kid in the family to go to college—feels she didn’t have an idyllic childhood, why she feels the way she does, because “he thinks he was there for all of it.”

Natasha can’t make him feel the pain of what he couldn’t see: The time she was pulled over while driving her white 19-year-old niece around, how the officer kept looking in the back, asking a grown woman if she was all right. The time a campus cop at St. Joseph’s stopped her for no reason, letting her go only after learning she was on the basketball team. The litany of similar incidents and microaggressions, right in her own backyard.

Cloud cut off electronic communication with Eric around the time she and Ocasio were throwing together a courthouse wedding last October, before Election Day. “He couldn’t fathom how voting for [Trump] was voting for someone trying to endanger his own sister’s rights, that we were rushing to get married to protect ourselves in case he got reelected. It was too much. I was done,” she says. (The two still see each other at family events.)

“Seems like I was never white enough and never Black enough. The thing is, I walk outside and you see me as a Black woman.”

Eric, for his part, regrets how his relationship with his youngest sister devolved. “I could see how she might be upset,” he says. “I did respond to one of her social-media posts by saying she was a puppet for Converse, that she wouldn’t post over-the-top social-activist stuff if she didn’t have that endorsement deal.”

Sharon has tried to play peacemaker, full of remorse about the footing on which her biracial, bisexual daughter began her adult life. She had never pressed Natasha to talk about race while growing up. “We were blind to a lot of that,” Sharon says. “She was just one of us. We didn’t see it as a Black-and-white thing. But now I realize. . . . And I’m just sick about it.”

Her family’s rift is America’s rift writ small, and her daughter has become a spokesperson for the side who’s hurting the most. It’s terrifying. “We’re more scared for her,” Sharon says, “than she is scared for herself.”

When Colin Kaepernick emerged as the new conscience of pro sports in 2016—kneeling while the national anthem was played during NFL games—it rekindled memories of decades-old athlete activism: of Tommie Smith and John Carlos’s Black Power salute at the 1968 Mexico City Olympics, Muhammad Ali refusing induction into the Army during Vietnam, Arthur Ashe shedding light on South Africa’s apartheid.

But Kaepernick had many detractors in the Black community, who privately wondered why a biracial man, whose adopted parents were white and who had grown up in a white community, could come to symbolize their struggle. Brando Simeo Starkey, an editor at the Undefeated whose book, In Defense of Uncle Tom, delves into the problems around approaching Black identity as a monolith, has an explanation.

“Although a person not raised in close proximity to Black culture might not [initially] cultivate a strong Black racial identity, developing one isn’t particularly difficult,” Starkey says. “White skin grants a person exemption from race-based injustices. Black skin makes one vulnerable to all manner of race-based injustices. Once the epiphany strikes, once a person becomes convinced of the idea that race is a central organizing factor of American society, we should expect some people who arrived late to that conclusion to put in extra effort, perhaps to atone for past naiveté, maybe to make up for lost time.”

Cloud has. She heard the silence when she was coming up, from Charles Barkley, from Shaq. Last year, Michael Jordan pledged to donate $100 million to Black Lives Matter, but Natasha still remembers Old Mike, who stood for, well, Nike, Haines, and Gatorade, the one who infamously refused to endorse a Black Democratic candidate in his home state of North Carolina against Jesse Helms because, as he put it, “Republicans buy sneakers, too.” (Jordan said in the 2020 documentary The Last Dance that the comment was uttered in jest.)

“You are Michael Jordan—you literally have the power to change and influence the world,” Cloud says. “I love Michael. But all he had to do was say, ‘I support this man running for office.’ People [had] literally [been] lynched in your hometown community . . . . And you’re not going to speak up? That, for me, I was like, ooooohhhhh.”

A generation or two ago, Cloud might have contended with the costs of speaking out. Because look—there were athletes not named Michael Jordan who called out discrimination and suffered for it.

Washington first heard from Cloud in 2019, when she lit into DC mayor Muriel Bowser and DC Council member Trayon White. Cloud had gone to read books to kindergartners in the Washington Highlands neighborhood and gotten a soul-crushing earful about violence engulfing the community. After the event, she got into her car, refreshed Instagram, and uploaded a video plea. “Trayon, you are the representative for Ward 8, so I’m calling you out. I just left Hendley Elementary School. And do you know that they had to cancel their Field Day today because at 4 pm yesterday a bullet went through their front window? In fact, it’s the third bullet this month that’s gone through their front window. And nothing is being done!”

In protest, Cloud and the Mystics enforced a media blackout after that week’s game. She was the only member of the team to speak after a loss, and she would only address the gun violence plaguing children in DC.

The following spring, she watched all eight minutes and 46 seconds of the video that shattered the country, of the white Minneapolis police officer named Derek Chauvin suffocating to death a Black man named George Floyd. “If you’re silent, you are part of the problem,” she wrote in an essay for the Players’ Tribune shortly after the killing. “If you’re silent, I don’t f— with you, period.”

It was a few weeks later that she announced she’d sit out the 2020 season. “I am more than an athlete,” she explained on Instagram. “I have a responsibility to myself, to my community, and to my future children to fight for something that is much bigger than myself and the game of basketball. I will, instead, continue the fight on the front lines for social reform, because until black lives matter, all lives can’t matter.”

Gone was her $117,000 salary, and a chance to repeat as WNBA champion with her teammates. She was one of 15 players to opt out of the shortened season at the league’s Covid bubble in Florida and one of just four to do so for advocacy reasons.

A generation or two ago, Cloud might have contended with the costs of speaking out. Because look—there were athletes not named Michael Jordan who called out discrimination and suffered for it with the gradual ending of their careers. But the awakening of 2020 has meant that activist athletes are no longer dismissed as a liability. Kaepernick—he has gone from an NFL pariah to a multimillion-dollar pitchman for Nike’s social-justice initiatives.

Thus, instead of dropping her, executives at Converse—now in comeback mode in the hoops-sneaker business—ran with Cloud’s new brand. They held fast to her endorsement deal but also decided to do something unheard of: cover her forfeited 2020 salary for not playing basketball in their shoes.

“I cried thug tears,” Cloud told Ketsia Colimon, the team’s longtime spokesperson.

Cloud wasted no time. Before NBA and WNBA players entered their respective pandemic bubbles to play ball in Florida last summer, confusion reigned. Athletes had concerns about contracting Covid, and they weren’t getting the answers they needed; many were scared. For the women, it wasn’t as if the risk to their lives would come with monster paydays. The average WNBA salary of $130,000 is—wait for it—49 times less than the average NBA salary of $6.4 million.

So as bubble talks began, Cloud finagled herself onto a union call with NBA players and reminded them of the grim financials, preaching unity and asking them to consider helping the women secure more leverage.

Chris Paul, the veteran NBA point guard and union president who’s been an advocate for Black Lives Matter, was impressed and began to mentor Cloud. She called Kyrie Irving, the Nets’ All-Star who had sounded moved by the WNBA’s predicament during the union call. They spoke again. And again. Late last July—with a public hat tip to Cloud—Irving announced a $1.5-million donation to help subsidize WNBA players who chose not to play in 2020, whether because of coronavirus or for social-justice reasons. A financial-literacy course was also added, a $20,000-per-player gift. The maneuvering caused the league to allow its athletes who didn’t want to play to do so without consequence.

“My message was simple and straightforward,” Cloud says now. “I was like, ‘While a lot of you are feeling different things for not wanting to play in a bubble, many of you can afford to do so. Unfortunately, the women don’t have that luxury, even though so many of us feel the same way.’ I made it clear our message would be even stronger if we combined forces.”

A month or so into the season, Cloud was again working behind the scenes. Video had emerged that showed police shooting and killing a Milwaukee man named Jacob Blake as he got into his car. The city’s team was staging a walkout in protest, and Mystics players were struggling with how to respond. “We had to call Natasha,” says Ariel Atkins, a teammate. “She wasn’t playing and technically wasn’t on the team at that moment. But we’re talking about a huge vocal and emotional leader for us.”

Cloud inserted herself into conversations between Mystics players and other concerned players. The women wanted a temporary suspension of play, not so palatable a prospect for the networks or the league owners who cash in on broadcast rights. “You won’t be punished for making this decision,” she told teammates on one call.

“She didn’t necessarily tell us we had to do it,” says Atkins. “I just remember her being super-adamant about gauging where we were, telling us to ‘listen to our heart’ and asking us, ‘What do you feel?’ She’s always been the voice that points us in the right direction.”

The league relented, and the two-day work stoppage culminated in what became the lasting image of the 2020 WNBA season: the Mystics and three other teams linking arms and kneeling together on the court, a searing show of unity before the official lockout announcement.

Cloud looked for other ways to assert influence during the year off. At home in Philadelphia, she partnered with Malcolm Jenkins of the Eagles to begin talks with the city’s law enforcement about civilian oversight of the agency. And as the presidential election approached, she enlisted in various acts of resistance. After seeing tweets about a Florida woman arrested for allegedly striking a “Women for Trump” sign and then providing a false name to police, Cloud found out how to pay her $500 bond and bailed her out. “Go live your life, sis,” she declared on Twitter.

“We had to call Natasha. She technically wasn’t on the team at that moment. But we’re talking about a huge vocal and emotional leader for us.”

Finally, when she heard that the Atlanta Hawks would be using their arena as a Georgia voting center, Cloud reached out to officials at Monumental Sports, which owns the Mystics as well as the NBA’s Wizards and the NHL’s Capitals, about doing the same thing at the Mystics’ arena in Southeast DC. It became one of the District’s largest voting centers.

In the year she gave up the game for something more gratifying, in what easily became the busiest and most productive year of her life, Natasha Cloud managed to keep doling out the assists.

Before the WNBA’s 25th-anniversary season began this spring, the Mystics and Monumental thought deeply about their strategy and branding moving forward—really, how did they want to be seen after 2020’s racial reckoning?

The more they mused, the more they moved toward moral clarity: One “woke” summer wasn’t enough. They would take their cue from the woman who now had dual roles: point guard for a team and for an organization. “Natasha is using her tremendous platform to inspire others to think differently, to challenge conventions and do more,” says Ted Leonsis, the chairman and CEO of Monumental Sports. “That is the same entrepreneurial spirit I share.”

As an homage to women’s suffrage, the front of the Mystics jerseys this season reads we shall not be denied. The team wants to amplify the messaging of the 19th Amendment so it now reflects equal rights in the voting booth and the corporate world—to take a stand on equity, on LBGTQ equality, and on gun violence, especially in the Southeast DC neighborhood where they practice and play.

Leonsis, who often speaks of the “double bottom line,” or the need for corporations to balance their profit margins with philanthropy, understands the value of his built-in brand-builder. He says he fully supported her decision not to play: “Sports fans are the most purpose-driven people you will ever meet. They are passionate about their athletes, their teams and their issues. So when they identify with an athlete like Natasha who speaks to them, brands naturally take notice and want to tap into that trust.”

All good, but at the same time it’s fair to ask: Is T Cloud (to her Insta fans) now a ballplayer or a movement? How do you balance the two?

After all, the pro athlete who’s putting up career-high numbers this comeback season is the same Black woman who has been sleeping next to a night table with a 9mm Smith & Wesson handgun she purchased last year—just in case. (She bought it amid worries about unruly neighbors and took gun-safety lessons from Ocasio’s father, a longtime gun enthusiast.)

Cloud lets out a long sigh. “I think I’m built for it now. [Last] summer was good to lay my groundwork. Put everything in motion. Sounds cliché, I know, but that whole champion-on-the-court, champion-in-your-community thing? I feel like I’m closer to that.”

Validation came swiftly, especially after the Players’ Tribune essay. Since “Your Silence Is a Knee on My Neck” was published, college professors and high-school teachers have written to tell her they now use it as part of their curriculum. “Different corporations have emailed me to tell me they use it as part of their diversity-and-inclusion training. How dope is that?”

Almost as surreal as that preseason practice day earlier this year—April 20, to be exact—when Mystics players and coaches gathered around a TV in their training room. They waited. Waited. Then heard the words and exploded into applause, like an unheralded college team learning they’d be playing in the NCAA tournament.

“Guilty.”

Derek Chauvin, George Floyd’s killer, would spend the rest of his adult life behind bars for murder.

Lasting change comes embarrassingly slow in America, Cloud knows. “But you have to take the wins. And that verdict—‘guilty,’ three different times—that’s justice, that’s accountability.”

She was on the phone with Ocasio during the celebration. When the raptures subsided, she told her wife she loved her and would call her back soon. She texted her parents and some friends, dismounted her exercise bike, and walked back onto the court. Under the banner declaring the Mystics the 2019 WNBA champion, Natasha Cloud could almost hear her voice echoing back to her.

This article appears in the July 2021 issue of Washingtonian.