The Hagerstown Speedway is a dirt oval track about seven miles outside downtown Hagerstown, Maryland. Its red clay has hosted Bobby Allison, Jeff Gordon, and Ken Schrader since the facility opened in 1947. On Friday morning the track was dark, but there was a little action going on in its back lot, which overlooks the speedway’s quarter midget track. There, parked among some rusting trucks and the woods that lead north to Conococheague Creek, were the roughly 50 vehicles that made up the “People’s Convoy” before organizers declared “victory” Friday afternoon and said its members would head home within a week.

The convoy has been here before. It arrived at the racetrack in March, ready to do battle with vaccine and mask mandates, a few weeks after the Supreme Court struck down a Occupational Safety and Health Administration’s rule that required employees at some companies to be vaccinated against coronavirus or to test weekly, and a few days after DC dropped its indoor mask mandate, which had been a locus of right-wing ire during the Omicron surge. This left the convoy in the position of trying to explain what, exactly, it wanted from its stay in the DC area.

It settled on opposing the President’s ability to declare a state of emergency, but to anyone who paid the slightest bit of attention, the convoy’s goals were less esoteric: loud expressions of frustration, often in the form of honking, from people whose candidate lost the last presidential election as well as animus toward vaccines and government authority in general. So it’s not surprising that, aside from scoring some meetings with GOP members of Congress, the convoy left town 24 days later with nothing to show for its long days driving around the region and long nights in the cool and wet spring weather.

The group traveled out west, losing members and leaders along the way, before declaring in early May that they’d decided to return to Washington—or, you know, a racetrack 90 minutes away—to continue whatever it is they’re hoping to accomplish. Last week a new challenge arose: The group that had organized disbursing the nearly $2 million the convoy crowd-funded to members said the money pot had just about run dry and it would soon cease work with the group. Since the convoy returned to Hagerstown this week, it’s taken one uneventful drive toward the District and hinted at trying to pull off an “occupation” in DC. Such a plan has yet to materialize. A couple of its most popular live-streamers have left. There was a fight the night before Washingtonian arrived on Friday morning. Not a lot was going on.

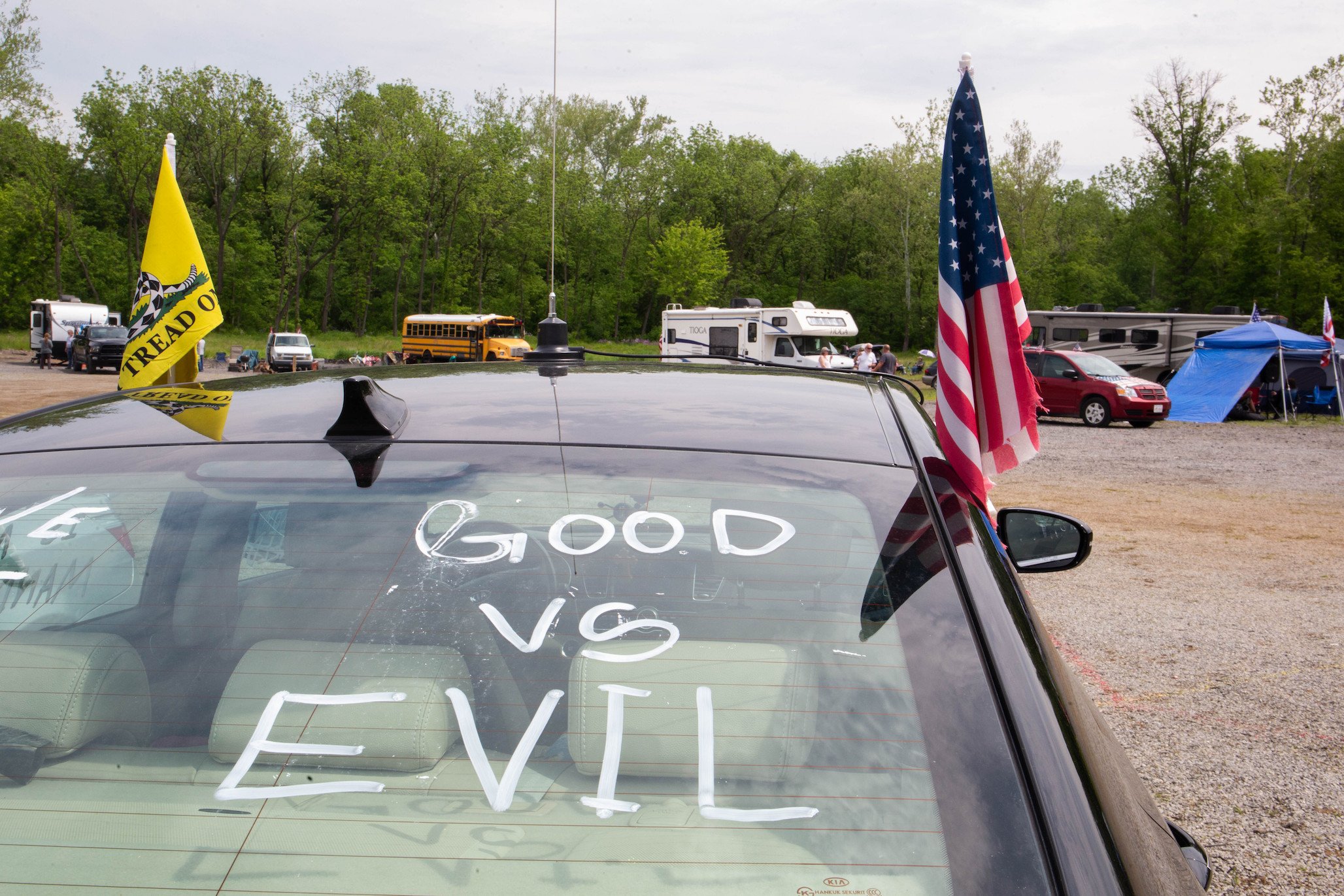

One convoyer stood near a crossover SUV parked near five portapotties. He was from Ohio and wore harem pants, a backwards baseball cap, and wood-grain sunglasses. His car, like most of the vehicles there, was festooned with messages: the Tupac lyric “Real Eyes Realize Real Lies,” for instance, and “Coerced Prick Is Medical Rape.” He spoke in a gush of lightly fact-checked grievances about the World Health Organization (actually running the US pandemic response), Anthony Fauci (apparently under investigation), and the perhaps-apocryphal “cobra effect” that some economists cite to explain perverse incentives (I had no idea how we landed on this subject, but he did assure me that cobras could be hunted in Great Britain). Pointing to one of the slogans on his car, he likened vaccinations to “getting penetrated to keep your job.”

Like many people I spoke with, he was frustrated with his elected officials, though the only one of his he could remember was US Senator Sherrod Brown, who he was not crazy about. He explained that US Representative Jim Jordan’s suggestion that convoy members go home and work on political campaigns had “dispersed our numbers.” Why not take that advice and work to elect like-minded people? I asked. Wouldn’t that be a better way to accomplish your goals? He said he he preferred to try to effect “change, whether it comes from this convoy or the awakening that comes from this convoy.”

Others told me about their frustrations with inflation and high fuel prices. One woman from Florida, who unlike most of the people I met in Hagerstown was actually a trucker, said she’d heard diesel fuel might soon be rationed. Her banker, she said, had advised her to stockpile cash and food. She planned to stick around for a few more days but said she and her husband would soon need to get back on the road to make money.

My conversation with a man who gave his name as Ratrod will stay with me for a long time. I kept trying to ask him about his hot rod, which he explained he uses in convoy situations to encourage people to ignore red lights—”Why are you looking at the light when the sky says to go?” he asked—but he was more interested in airing his complaints about some of the live-streamers. “Everybody’s trying to make money,” he said, before demanding whether I paid taxes. When I said yes, he lectured me about how stupid I was, because I was paying for a President who “sniffs children.”

Ratrod said he dislikes Donald Trump as much as he dislikes Joe Biden, and that one of them should be sued and hanged—either Biden for his alleged child-sniffing or Trump for maybe lying about it. As Ratrod got warmed up, he complained about his fellow convoy members (“incompetent people”) asked whether Washingtonian could be purchased beside supermarket tabloids (yes) and returned to the subject of how stupid I was for paying taxes, which he said he refuses to do. Waving his arms at the sparse crowd behind the racetrack, he said, “This is all the people that are willing to stand up for the whole fucking country.” We agreed it did not seem like very many.