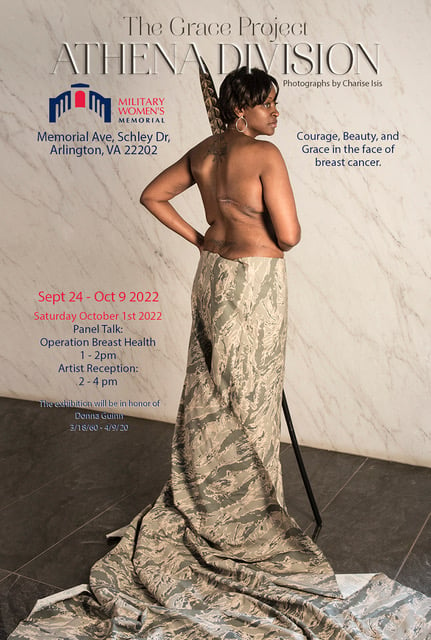

Previously a full-time boudoir photographer, Charise Isis knows how empowering it can be for women to pose in a photo shoot celebrating their bodies. Her latest project explores the same theme, photographing the mastectomy scars of breast cancer survivors who have served in the military. The photographer’s work will be the focus of “The Athena Division,” a free exhibit opening Saturday, September 24 at the Military Women’s Memorial in Arlington National Cemetery.

The inspiration for the exhibit can date back to 2009, when a woman entered Isis’s boudoir studio, remaining fully clothed.

Once Isis began photographing her, the woman shared that she was a 12-year breast cancer survivor and had undergone a mastectomy. She explained that she still felt mutilated, and her husband had booked the photo shoot, hoping it would help her feel beautiful again.

“All of a sudden, she just tore her shirt off and said, ‘Fuck it, I’m doing this for myself,” says Isis. “Behind the camera, I was thinking, ‘Oh, my God, I just witnessed a woman let go of 12 years of shame in one moment.'”

Unable to get the experience out of her head, Isis started her nonprofit, the Grace Project, later that year, photographing breast cancer survivors who have undergone mastectomies. Her goal? Help survivors find beauty and self-acceptance in their scars. Drawing on Hellenistic-period sculptures—chipped and weathered by time but still considered beautiful—Isis drapes her topless subjects in flowing fabrics, fashioning them as Greek goddesses.

The exhibit on display at the Military Women’s Memorial is a continuation of the photographer’s work, focusing specifically on 50 breast cancer survivors who are also active military servicemembers or veterans. Isis started the collection after reading a 2009 Department of Defense–supported study, which found that service members are 20 percent to 40 percent more likely to develop breast cancer.

“A lot of the veterans and servicemembers that I photographed were very emotional during their shoot,” says Isis. “A lot of women veterans felt like, because they are serving with a lot of men, they needed to be tougher than the men. Some of the women actually said that they had never allowed themselves to feel anything about their cancer while they were going through it.”

This portion of the Grace Project is called “The Athena Division,” named after the goddess of war in Greek mythology. Keeping in line with that theme, Isis drapes her military subjects in camouflage as a way to honor their service.

“The way she dresses survivors and patients focuses on the beauty that the world doesn’t usually see,” says Demetrica “Meechie” Jefferis, a breast cancer survivor and Air Force veteran photographed by Isis. “All they see is cancer, so it’s showing the world that there’s beauty even in the midst of that.”

At first, Jefferis, who underwent a double mastectomy followed by several reconstructive surgeries, had some reservations about her photos entering the public eye.

“I didn’t want to be offensive to people,” says Jefferis. “But after thinking it over and speaking with a dear friend of mine, [I realized] I’m going to let the world know that we don’t to hide our scars. The world needs to see this.”

Plus, she adds, her scars are now reminders that she was victorious.

Isis also incorporates props into her photos, such as swords, arrows, and crowns, which felt like fitting symbols for Sheila Johnson. The Air Force veteran was diagnosed with metastatic breast cancer in 2009 and photographed by Isis last month.

“Sometimes I call myself a princess warrior, and that’s how I felt [during the photos hoot],” says Johnson. “I had my crown on and was holding a sword and, in that moment, I felt so powerful. It reminded me of my military service, which made it extra emotional.”

Jefferis and Johnson, both breast cancer advocates, will speak on a panel at the gallery on October 1, discussing breast cancer disparities between military members and civilians as well as among different racial groups.

“I had two statistics against me,” said Johnson. “First being that I’m a veteran, and then also that I’m a Black woman. Black people are still more likely to get diagnosed at later stages and die at higher rates.”

Ultimately, Johnson and Jefferis hope the gallery and panel invite more conversations about breast cancer, spreading awareness about its prevalence among military members. One detail visitors to the gallery may notice is how young many of the survivors are: Jefferis and Johnson want other young service members to be aware of the risk and advocate for themselves, asking for mammograms earlier than the recommended age of 40 or 50.

“We need to have an open conversation of why so many women—and men, too—in the military are getting breast cancer,” said Johnson. “What are we doing wrong?”