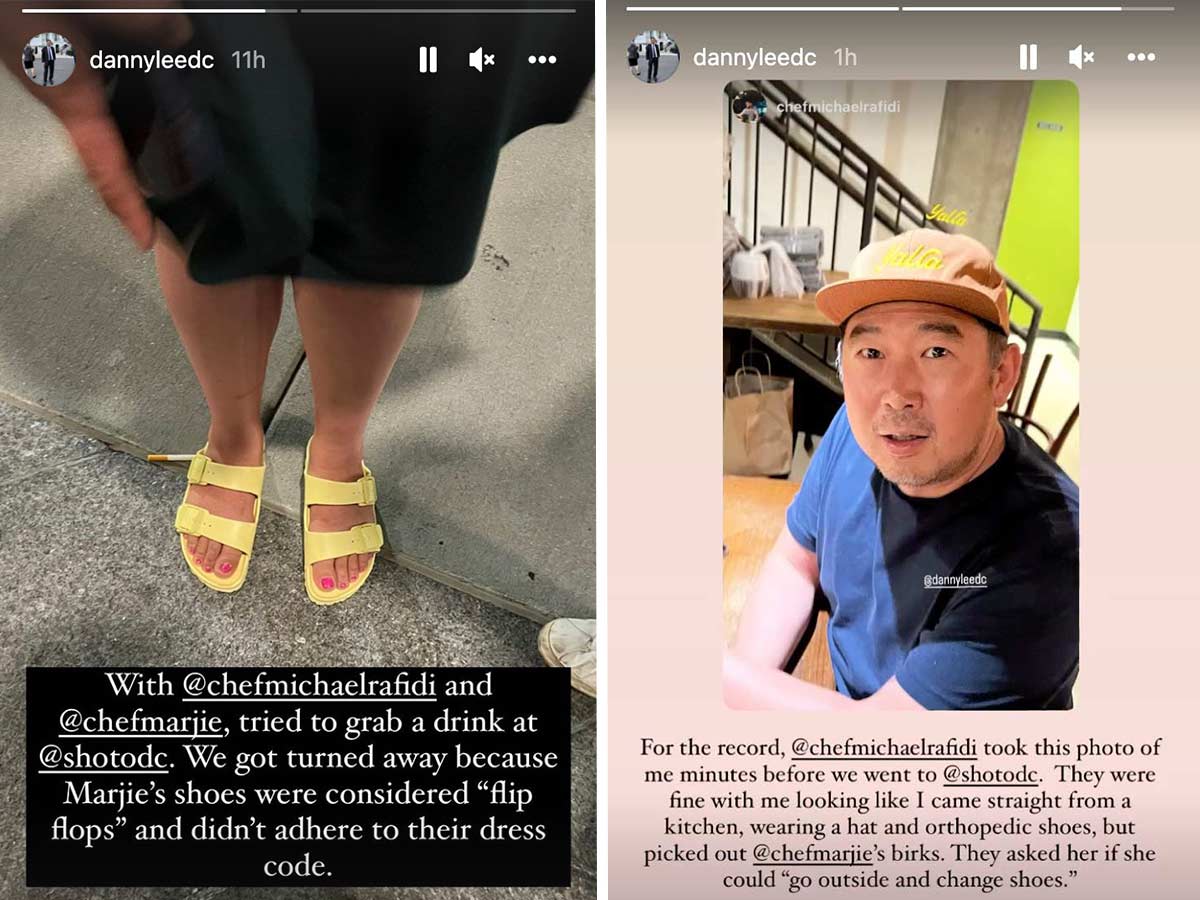

It doesn’t take anything too extreme to reignite the restaurant dress-code debate—take Birkenstocks. Over the summer, Top Chef finalist Marjorie Meek-Bradley was turned away from the downtown DC restaurant Shōtō for wearing the trendy sandal, which didn’t fall in line with the Japanese hot spot’s “elegant and smart casual” dress code. On its banned list: athletic wear, beachwear, and flip-flops. Which category, if any, Meek-Bradley’s yellow Birks fell into is—like dress codes themselves—a bit subjective and confusing.

When her dining companion, Anju co-owner Danny Lee, shared the incident on social media—along with a photo of himself in a T-shirt, ball cap, and orthopedic shoes—it sparked outrage. Why wasn’t Lee also given the well-heeled boot?

“To be clear, the reason why dress codes are problematic is because it’s impossible to enforce them with any consistency,” Lee wrote on Instagram. “This enables sexist/classist/elitist/racist thought to guide the enforcement of these ‘codes.’ ”

Dress-code critics often point to the 1970s, when American restaurants adopted them as an “acceptable” way to bar Black patrons in the post–Jim Crow era. As the hospitality industry grapples with inclusion and diversity, many view the practice as outdated and inherently problematic. And yet Shōtō is part of a growing number of new DC restaurants that are embracing rules of attire.

After two-plus years of people eating in their pandemic best—athleisure or plain ol’ sweatpants—some dining rooms are speaking up about wanting guests to ditch the drawstrings. Shōtō co-owner Arman Naqi insists it’s his customers who help guide the policy: “We have a regular who comes in three times a week who told me, ‘Please protect the ambiance at the restaurant. This is what makes the buzz and feeling special.’ ”

Shōtō’s Midtown Center neighbor Philotimo asks for “casual elegant” dress in its Greek tasting room and advises against “sports attire” and hats. Over in Dupont Circle, the retro Mayflower Club implores patrons to “approach your wardrobe deliberately and with a sense of occasion. You are welcome if you dress with personality, purpose, and originality . . . .” In case ‘purpose’ is too vague, a list of verboten items runs from ball caps to shorts to “visibly revealing” clothing.

More restaurant websites are eschewing dress codes in favor of fashion advice—chatty tidbits that feel more like a friend’s answer to the age-old “What should I wear to dinner?” question.

“We do not have a dress code. But . . . if we did, it would be fancy,” reads the website for the two-Michelin-star Capitol Hill tasting room Pineapple & Pearls. “Something along the lines of emerald green tuxedo dinner jackets and gold sequin dresses (or your best New Year’s Eve outfit).”

Do its diners really dress the part? “Baby blue. Millennial pink. Every color of sequin—you name it,” says chef/owner Aaron Silverman. The $325-per-person tasting room shows off photos of its “best dressed” diners on Instagram.

View this post on Instagram

The restaurant had no dress code pre-pandemic, but when it reopened in May after a two-year Covid closure, Silverman reconsidered: “We had so many guests ask what they should wear to capture the vibe and energy of the evening—so we came up with this approach.” To be fair, he adds, “That is how we are dressed! Our team is in bespoke, custom-made maroon-and-black velvet tuxedo dinner jackets with silk-lined Pineapple & Pearls–motif interiors. Everything from the length of the lapels in millimeters to the interior material of the pockets was designed from scratch.”

Leading by example is indeed en vogue. At the flashy Italian newcomer L’Ardente near Penn Quarter, the drapes are Missoni, the glass Murano, and the fashion decree “glam Italian” to match. “We wanted to encourage people to dress up and celebrate that Covid has come to an end, but we’re not terribly specific,” says co-owner Eric Eden, who formerly operated two Georgetown fashion boutiques. “ ‘Glam Italian’ can mean a pair of heels and a gown or rolled-up jeans and a tank top. In this wonky town, it’s nice to see people take some chances,” Eden says, noting, “Someone dressed casually is equally able to spend as someone dressed to the nines. Sometimes more so.”

“It’s really hard for me to separate dress codes from their history as a tool of division and control, says Rooster & Owl co-owner Carey Tang.”

Rooster & Owl, the prix fixe destination near Columbia Heights, sends out a more modest message. A lengthy FAQ page reveals: “Our general guidance is if you’d be comfortable meeting your partner’s family in what you’re wearing, then you’re dressed appropriately.” Still, co-owner Carey Tang says she’d never turn away a customer: “It just means, you know, shirt and shoes. Be respectful with context. Come as you are.”

She and chef/husband Yuan Tang never considered an actual dress code for their restaurant, even as it rose in the Michelin ranks to gain a star. “It’s really hard for me to separate dress codes from their history as a tool of division and control,” she says. “Instead of being an indicator of ‘respect’ for the restaurant, it just feels exclusionary—and puts a lot of pressure on the front-desk team to arbitrarily enforce rules that have a lot of coded meaning.”

Rooster & Owl does offer loaner accessories for diners—but they’re far from the dinner jackets of yore. In the Tangs’ closet: bifocals to help decipher small print on the menu and cotton shawls or hooded sweatshirts with the restaurant’s slogan (fly together) for chilly diners.

Meanwhile, jacket requirements have largely gone the way of the doily and dining-room pianist. Clyde’s Restaurant Group director of operations David Moran, who started working at the company’s venerable Georgetown restaurant 1789 when it required sport coats in the ’90s, remembers the shift: “It coincides with DC becoming a real restaurant city. When Michel Richard opened Central [in 2007] and great chefs were going casual, diners realized they didn’t need to sit in a suit and tie to have a great meal.” 1789 ditched its jacket rule in 2011.

Today, the Clyde’s Group is dress-code-free. At its Old Ebbitt Grill, DC’s longest-standing restaurant, Moran actually directs his host staff to run after casually dressed tourists who swing through the revolving door, take a look at the Victorian setup and staff in bow ties, and swing back out.

“We’ve trained our managers to say something like, ‘We dress because we have to—you don’t,’ ” says Moran. “The last thing anyone wants to do is chase business away these days.”

This article appears in the November 2022 issue of Washingtonian.