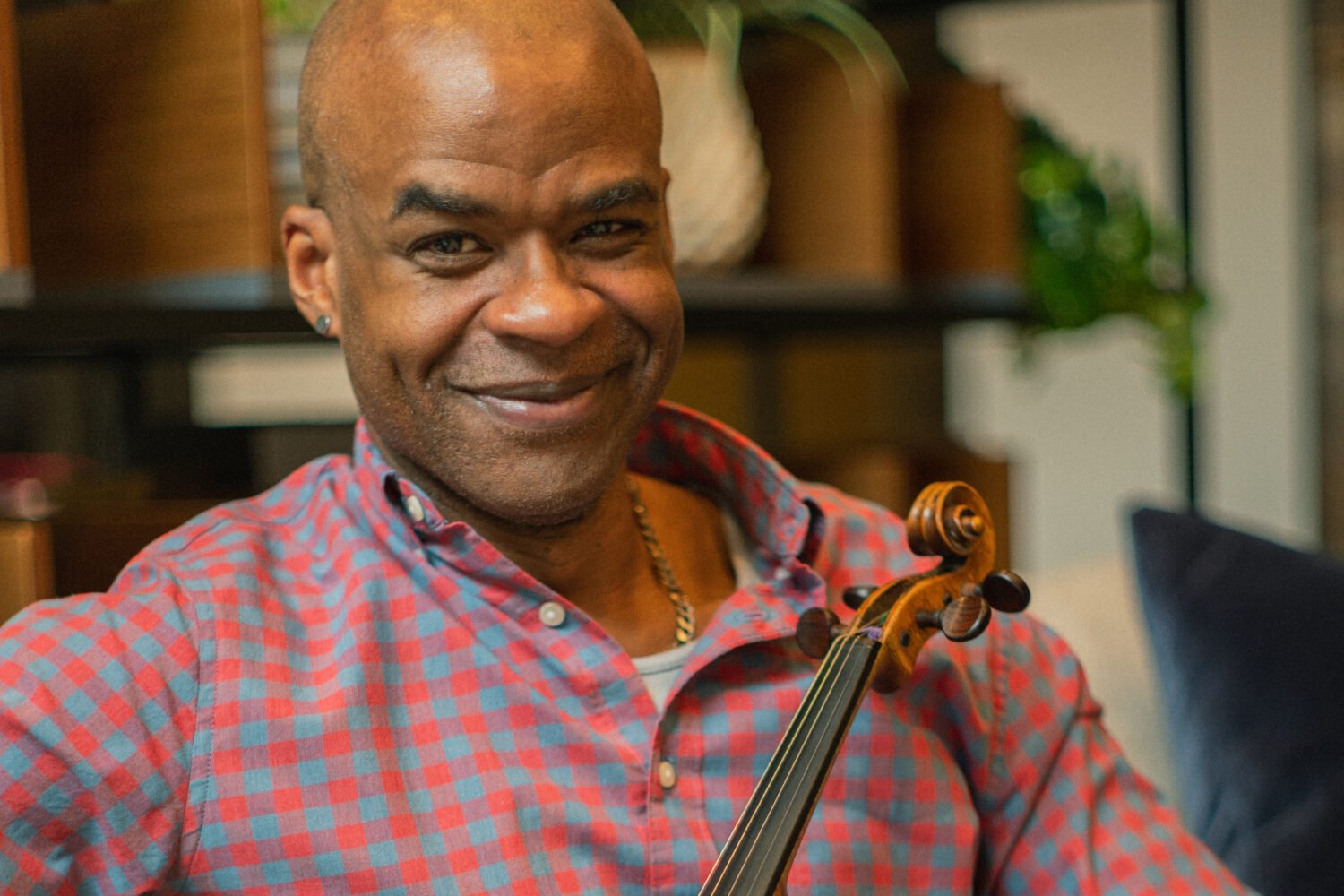

Wesley Lowery’s first book, They Can’t Kill Us All, was published the week after Donald Trump was elected in 2016. The Washington Post reporter had covered the rise of the Black Lives Matter movement in response to police violence in Baltimore, Cleveland, and Ferguson, Missouri, among other cities, and his book explored and expanded on those experiences. Lowery knew Trump’s victory was going to have a massive impact on the issues he covers. Now he’s back with another look at race in America, this time through the lens of the white-supremacist movement, which has been so accelerated and emboldened by Trumpism. Its provocative title: American Whitelash.

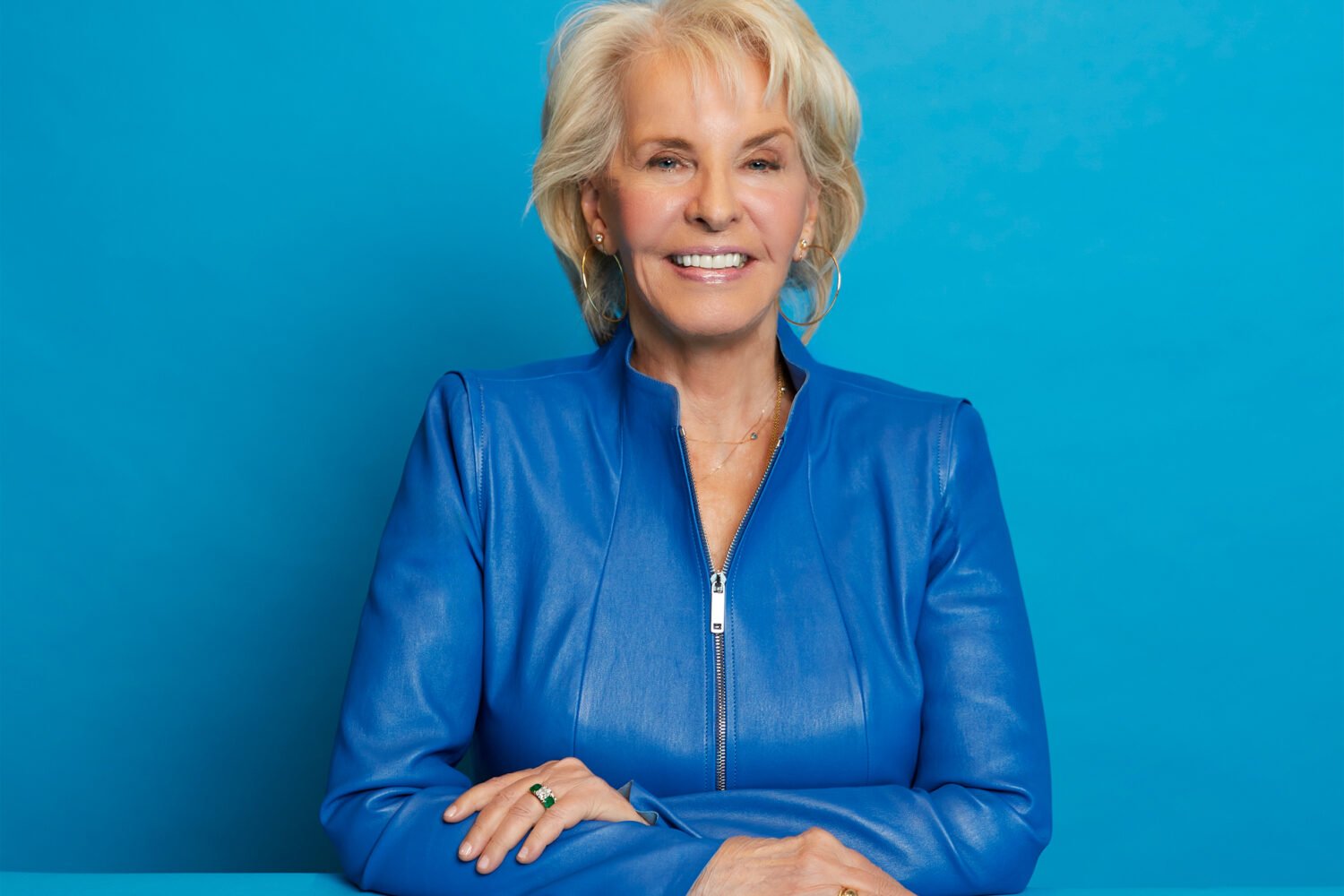

Lowery left the Post in early 2020, following high-profile clashes with former executive editor Marty Baron. He spent two years as a correspondent for CBS and was just hired as a professor at American University. He also writes for the Post and other outlets, often about the role of journalism in a post-Trump world. We met at a brewpub near his home in DC’s Eckington, where he talked about two of America’s defining subjects: race and violence.

When Obama won the presidency, there were people who didn’t vote for him who still thought it was an important moment—that perhaps we’d moved past our racist history. But you write that white supremacists used that to coalesce around the idea that they were losing this country. Do you think the US would have been better off in the long run if John McCain had won?

Anytime you have Black and Brown Americans, or immigrants of any sort, who are asserting their humanity and demanding their rights and equality, people who perceive themselves as the losers of that equation are going to lash out in this way.

At some point, we were going to have a Black President, whether it was Barack Obama or someone else. It is unclear, with what John McCain’s politics were, especially on immigration, if it would have stemmed this type of growing tide. McCain himself acknowledged before his death that you see a movement growing within the Republican Party, as personified by Sarah Palin, that was far outside of his control. Having someone named Barack Obama on the ticket certainly helped [boost white supremacists]. But I’m not sure [a McCain presidency] would have done much more than mask it for a short term.

On top of Obama’s presidency, there were census projections that the US would become majority-minority in 2050. That fed this whitelash, as you call it, along with an unpopular war, a financial crash, and a revolution in communications.

Think about the difference between 2007 and where we are today—what’s changed in news environments, the rise of broadband wireless. We just exist in a night-and-day-different world, technologically.

The Tea Party was an early and prominent reaction to these changes. You got into trouble at the Post for tweeting that the Tea Party was a “hysterical grassroots tantrum about the fact that a black guy was President.” Is this book a way to flesh out that theory?

My tweet was glib. I would not have written that sentence in a news article in the Washington Post. But it was a true statement. Every study that has looked at this has shown that this movement on our political right, no matter what we want to call it—Tea Party that turns into MAGA—racial animus is one of the driving factors. We know that Tea Party members were more likely than the average American or the average Republican to hold higher levels of racial animus. Polling showed January 6 participants were more likely to come from a place that had seen massive demographic change than a place that hadn’t.

Donald Trump builds a largely white coalition of people based on the promises of building a wall at the southern border to keep the scary Brown people out and shutting down travel from Muslim countries. I covered parts of the Tea Party—I covered Congress for the Washington Post in 2014. It is very clear that at the core of the political response to Barack Obama is clear nativist racial animus from the white-majority population of our country. And that animus plays into the hands of the even smaller subsection of people who are avowed white supremacists who want to start a race war. You don’t have to conflate those two to understand them—one helps the other.

It was reported at the time that Post higher-ups felt this was a better topic for activism than for journalism.

My boss at the time suggested I didn’t have the requisite expertise on these issues.

“When the facts show something, journalists shouldn’t pretend that they don’t show that.”

That line between journalism and opinion is something you’ve thought and written about a lot in the last few years.

The institutionalized mainstream media is very often a lagging indicator, right? I think that among the worst continual failures of our mainstream media has been an inability to have clarity in moments of racialized violence. The way we handled lynchings across this country for a long time, for example. So often as an institution, we have been party to our collective society’s failures, as opposed to being the one institution that figured out the right way to handle this or that.

It was clear to anyone whose professional life is not contingent upon having Republicans return their phone calls that there was a rising nativist movement in America in the decade following Obama’s election that had seized control of a not-insignificant part of the Republican Party. And that that movement included and was encouraging people who were actively committing acts of violence against people of color. And if you’re not concerned that the Trump White House won’t return your call, or that [former speaker of the House] Paul Ryan’s office won’t return your call, there’s no issue, there’s no opinion/fact debate here. I think that is where there has been a lot of frustration, not just for myself but for a lot of other journalists of color—that when the facts show something, we shouldn’t pretend that they don’t show that. And so there was, you know, some good-faith disagreement there.

I’m sure Marty would be happy to hear that. Do you two talk at all?

We haven’t spoken.

That’s sad. At one point, you had a pretty good relationship. I mean, he brought you down here from the Boston Globe.

Yeah, it is. I’m looking forward to reading his book [about Trump, Washington Post owner Jeff Bezos, and the future of journalism] later this year. There have been a number of times where I’ve thought about shooting him a note, but I want to wait, in part, because I know he’s working on the [book]. It’s not that I’m so arrogant to believe I will be in it, but I wouldn’t ever want to come across as trying to influence anyone. He should write his recollection of how things happened.

But your book is not a letter to Marty. You’re not trying to say, “See, I was right”?

No. I was working on it well before anything happened between the two of us. Frankly, sometimes the sign of a good editor is that they’re in your head while you’re writing. I’m sure there were some elements of that as I was writing.

Talking about editors reminds me of the very beginning of this book, where you write that you won’t capitalize “black,” as many outlets began to do after 2020—including Washingtonian—or “white,” as the Post does, because race is a fiction. Can you unpack that?

I’m happy to. I remember as this conversation began playing out, I initially didn’t feel strongly about it in one direction or the other. Not that I don’t think Black Americans have a unique history and culture. I obviously believe all those things.

When I read these types of capitalizations, very often what it does, in essence, is put an emphasis on race as a definitional quality of a person. I just felt like in writing a book that was explicitly about white supremacists—people who believe there are biological differences [between races]—it was extremely important to me not to do anything that could encourage the type of thinking, explicitly or implicitly, that there are some type of definitional races. Because there are not.

Beyond language choices, are there ways journalists could be doing a better job covering white supremacists?

We do a little too much “Nazi next door” coverage sometimes, as opposed to covering these people like we would cover ISIS, like we would cover al-Qaeda. These are terrorists hoping to upend the way our society works and to take us back to forms of societal interaction that we’ve advanced beyond. And these are people who would commit genocide, who would start a race war, and who are determined to prevent us from having a multiracial democracy. I think we have to have clarity about that. That doesn’t mean we can’t be empathetic to individuals; it doesn’t mean we don’t do journalism about how folks get into this. However, we have to be thoughtful about how we engage.

This article appears in the July 2023 issue of Washingtonian.