On Monday, an enterprising gentleman from New York City filed suit against Taco Bell for false advertising, claiming that a Mexican Pizza he purchased last September contained “approximately half” of the filling depicted in ads. Apparently, he felt hoodwinked by the pictures, swindled out of his precious $5.49 plus tax. Now he’s seeking damages—both for himself and for other alleged victims. Godspeed, my valiant knight.

When I first read that it’s a class-action suit, I thought I might be part of the class. Do I regularly eat Taco Bell? You bet. Do some of those items come out skimpier than suggested by the photos on the order screens? Obviously, yes. But the lawsuit turns out to exclude me; it’s only for people who have purchased three or more Crunchwraps or Mexican Pizzas at a New York State Taco Bell since July 31st, 2020. (Taco Bell did not immediately respond to a request for comment on the suit.)

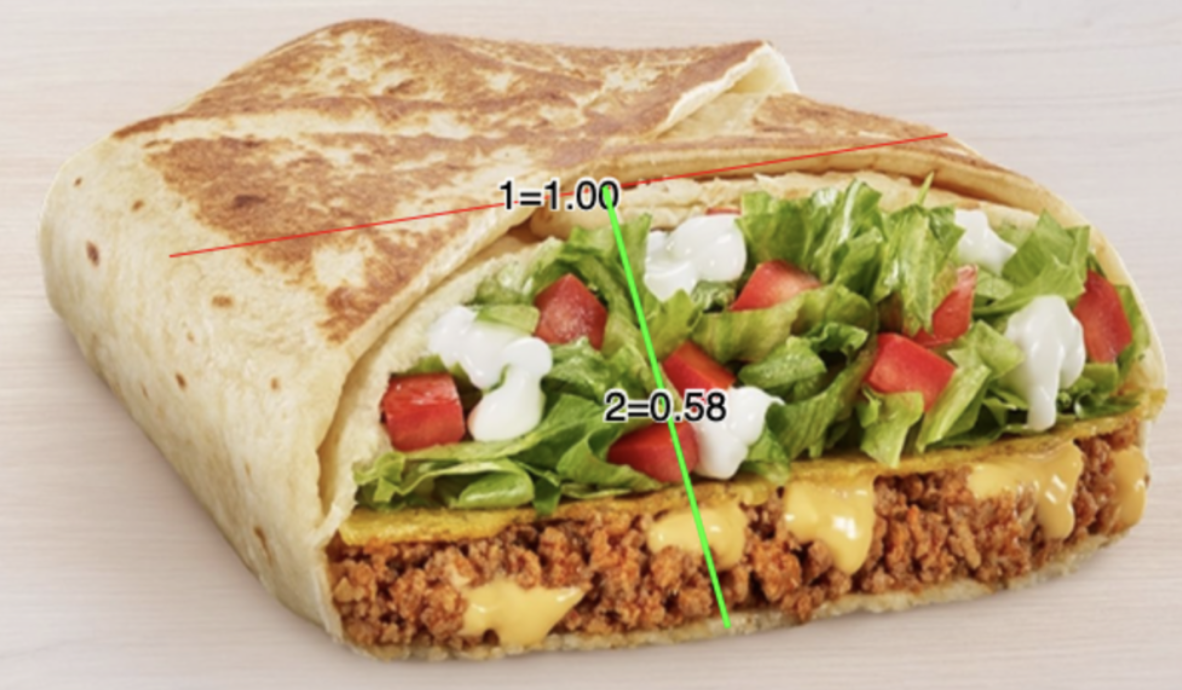

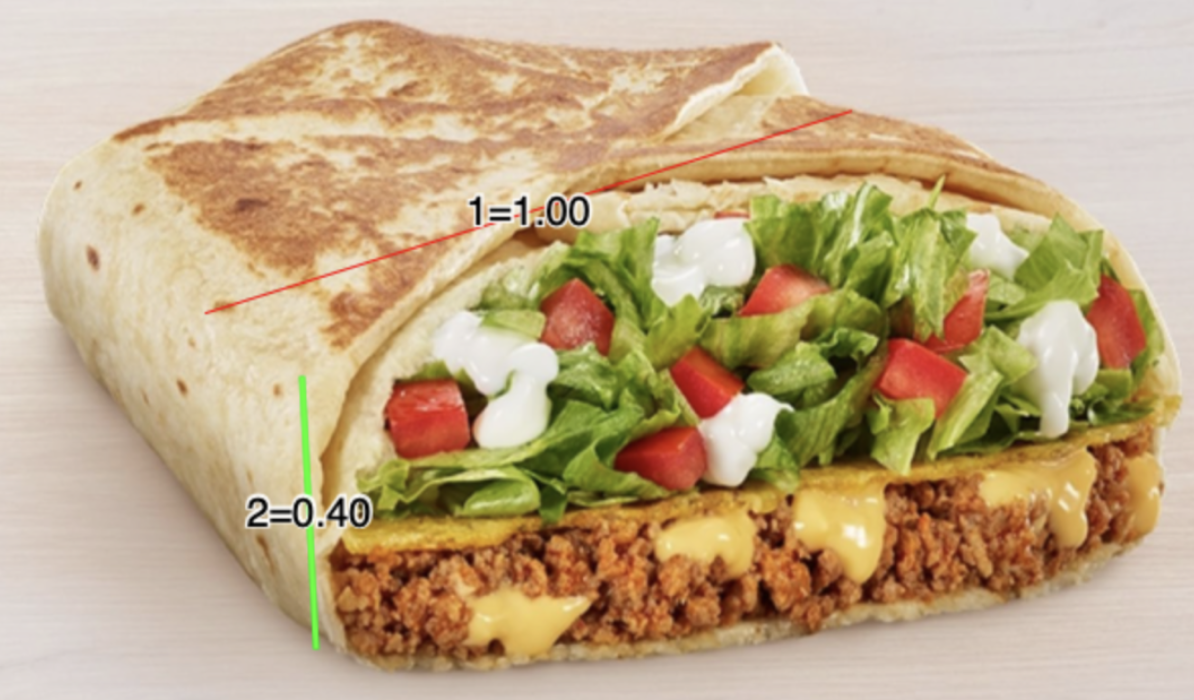

Nonetheless, some evocative imagery from the court filing has remained lodged in my mind:

Ruminating on these photos, I began to ask myself, might the logic of the lawsuit also apply to this region? Probably, right? It’s not like Crunchwraps would be uniquely under-filled in New York. So I decided to investigate: Are our local Taco Bells courting a lawsuit by skimping on beef?

This will be a journey in four parts. Please come along to learn what I found.

Part 1: Taco Bell—Rockville, MD—Crunchwrap Testing

On the afternoon of Wednesday, August 2, my husband, son, and I purchase one Crunchwrap Supreme from the drive-thru at the Taco Bell on Rockville Pike. Upon initial inspection, the Crunchwrap seems fine. We place it on the hood of the car to be photographed and measured. It is six inches across, and 3/4 of an inch deep. It does seem less robust than the advertising, but it strikes none of us as A) unusually small, or B) meeting the threshold for legal action.

Of the yet-uneaten Crunchwrap, I write in my notes: “It’s actually a gorgeous little meal, hexagonal like a honeycomb, browned on each side, sophisticated origami folding.” My son thinks it resembles a “stork package.” This is an auspicious start.

While flavor is not at issue in the Taco Bell false advertising lawsuit, I will address it nonetheless: The first bite tastes a bit like Cheez Whiz. There’s a subtle crunch from a layer of corn chips, an effect much diminished by the mass of limp, doughy tortilla that surrounds it. (My husband feels this would be fine had I asked for “extra toasted.”) The meat is flavorful, but it’s not good flavor, per se. Too salty. There’s a little kick. You’re hit over the head with cheese.

So the taste is lackluster—but is the item understuffed to a legally actionable degree? “In my Crunchwrap days, I received a range of qualities,” my husband reflects, noting that he has eaten many “skinny Crunchwraps” but this one is not among them. He feels that today’s Crunchwrap looks “carefully prepared,” perhaps slightly larger than average. “So we just got lucky?” my son asks. “I think Taco Bell is on their best behavior,” my husband replies.

We all agree that, for $5.59, our Crunchwrap seems reasonable. After eating it, none of us feel good.

Part 2: Little Miner—Rockville, Maryland—Munchwrap Testing

According to the lawsuit, Taco Bell’s victims are not limited to snookered customers; competitors that “more fairly advertise the size of their menu items” may have also been harmed. One such establishment is local taco chain Little Miner, whose Americano Munchwrap is, essentially, a Crunchwrap: a polygonal quesadilla-esque meal filled with ground beef, tomato, lettuce, sour cream, and cheese, lined with a crispy layer of corn chips.

Comparing the Crunchwrap ad image to the picture of the Munchwrap on Little Miner’s menu, the Crunchwrap does appear better—it looks beefy and vibrant, an enormous and flavorful snack. Yet at $14, the Munchwrap costs approximately 2.5 times as much as a Crunchwrap. That invites an interesting question: Who would pay extra for a Munchwrap, when the Crunchwrap appears to contain more food? Put another way, might Little Miner Taco be damaged by Taco Bell’s allegedly deceptive advertising? It’s just a short drive down Rockville Pike to find out.

The real-life Americano Munchwrap is almost identical to the image on the menu. And, at exactly twice the height of the Crunchwrap I just purchased, the Munchwrap is indisputably more robust. Ironically, if one had to decide whether the Crunchwrap or the Munchwrap was depicted in the Taco Bell ad, one would probably guess the Munchwrap. By looks alone, this Munchwrap seems pretty good.

But then there’s the matter of flavor. By far, the Munchwrap is blander than the Crunchwrap. My son takes a few bites and says, “It doesn’t really taste like the stuff it has in it. Like, there were tomatoes but I didn’t taste them.” At Taco Bell, by contrast, “I can taste the ingredients, but they all taste fake.”

The other issue is the grease. The Munchwrap is so greasy. The interior is riven by veins of grease that bleed through the bottom, spurt across the top, and coat our hands and faces as we eat. “You look like a vampire who’s been sucking grease,” I tell my son, whose eyes grow wide with alarm. By this point, I have quietly stopped eating my portion, after finding its bottom absolutely drenched with oil. My son puts his down, too, saying ominously that “I don’t want my bloodstream clogged.” We do not finish our Munchwrap—not even close.

So, the question must be posed: If one were choosing between a Munchwrap and a Crunchwrap, and selected the Crunchwrap based on Taco Bell’s allegedly deceptive advertising imagery, would one have been hoodwinked? Would one be entitled to damages?

Thus far, our consensus is no. The Munchwrap contains perhaps twice the filling of a Crunchwrap, yet costs 2.5 times as much. It’s also essentially inedible due to the grease. My son calls the Munchwrap the “hypocrite cousin of the Crunchwrap,” since it costs more but isn’t as good.

Part 3: Home—Glover Park, DC—Further Investigation

By now, I’m wondering whether this false-advertising suit has any merit at all. I mean, even if a real-life Crunchwrap is smaller than the ad, it’s still a good value. And isn’t that the lifeblood of advertising? To make things look better than they are?

To fairly evaluate the lawsuit, it feels important to actually read it, so I do—all 14 pages. It weaves a tale of great misfortune: On September 20, 2022—after viewing Taco Bell ads online and in the store—Frank Siragusa ordered a Mexican Pizza. He expected it to have “a similar amount of beef and bean filling as contained in the pictures.” Allegedly, it did not. Siragusa was disappointed. But of his unsatisfying experience, his attorneys offer no documentation—instead, the suit cites images pulled from various places online: social media, digital publications, a Reddit thread.

For instance, the lawsuit’s image of the paltry Grande Crunchwrap Supreme is a screenshot from a YouTube video made by what appears to be an adolescent boy. With slicked-back hair, wearing a black suit and tie, he holds the allegedly inferior Crunchwrap up to the camera and says, sarcastically, “You can see how it’s just teeming with beef. Look at it, it’s overflowing with it. Can you believe how much meat is in this?” Afterwards, he adds: “The whole selling point of this item is for it to have two layers of beef, and there certainly is almost none in here.”

After citing various disgruntled internet users, the lawsuit drops the hammer, accusing Taco Bell of behaving “willfully, wantonly, and with reckless disregard for the truth.” To remedy Taco Bell’s supposedly “unfair and materially misleading advertising,” Siragusa wants monetary damages for himself and all others affected, plus a court order for Taco Bell to either stop selling the relevant items or start advertising them more accurately. In regards to the money, the legalese is tough to parse—but it seems like he’s asking for at least $150 for each person in the class.

Now, I must search my heart. Had I bought three Crunchwraps in New York that were equivalent to the one I got in Rockville, do I honestly feel that I would be entitled to $150? I do not, not even a bit. This puts me in an uncomfortable position. At first, I assumed Siragusa was a hero; now I’m siding with an enormous corporate entity over an everyday guy like me. It doesn’t feel right. I don’t like this conclusion. There must be evidence I haven’t considered, so I persist.

Part 3A: Home—Glover Park, DC—Crunchwrap Rabbit Hole

To be 100 percent sure of where I stand, I enter the “true-crime sicko” phase of my inquiry. The Crunchwrap I received was smaller than the advertised Crunchwrap, but I need to know by how much.

When I upload the allegedly deceptive Crunchwrap ad into an online image-measuring tool, it tells me that the advertised Crunchwrap’s height is about 58 percent of its diameter. Assuming that the diameter of all Crunchwraps is consistent—six inches is what I measured on mine—then I can use basic proportions to calculate its height.

Math, math, math. Blah, blah, blah. But in conclusion, the height of the advertised Crunchwrap appears to be a stunning 3.48 inches. Mine was 3/4 of an inch tall, about 20 percent of the advertised height.

Framed that way, I’m mad. Say you paid someone for five gallons of milk and they only provided one—would that be fine? Would they get to keep your money? No, I believe they would not. So maybe this lawsuit has merit.

For affirmation, I show my diagram to my husband, who immediately spots a flaw. “It’s not a clean cross section,” he explains of the advertised Crunchwrap, pointing out that there seems to be a tricky optical illusion at work. Not only have they sliced the Crunchwrap in half, but they’ve also apparently cut a semicircle off the top to give the impression of extra height. Deceptive? Maybe. But not literally false.

Based on his insight, I redo the calculation:

This time, it seems the advertised Crunchwrap is 2.4 inches tall. That is still about three times as tall as the Crunchwrap I purchased in Rockville—but my husband believes that my calculation is still wrong.

Using confusing terms like “compression” and “long camera lenses,” he explains that, essentially, the photo’s perspective doesn’t lend itself to the kind of proportional analysis I’m doing. Dealt this blow, I am at a loss. I do not know how to calculate the height of the Crunchwrap in the ad, and I therefore cannot determine by how much I might have been fleeced.

But when one line of inquiry closes, another one opens: What I’ve learned is that there are ways to photograph a Crunchwrap that—while perhaps optically deceptive—do not literally involve stuffing it with extra filling. Is it possible that the reverse is true, too? I look back at images of the Crunchwrap I bought and notice something odd: In the pictures, it looks really skinny—perhaps to a legally actionable degree. It’s much skinnier than I remember. In life, it wasn’t disappointingly small.

From this, my husband arrives at a provocative conclusion: that “it’s possible for a well-appointed Crunchwrap to photograph poorly.” Right. All images can be misleading—ones in lawsuits, and in ads.

Part Four: Taco Bell—Ridgewood, Queens—Testing the Restaurant in Question

At this point, I am engulfed in confusion. Maybe the plaintiff is an ambulance chaser. Maybe he’s just whiny, unable to cope with the universal human experience of ordering regrettable fast food. Or maybe the blame rests on Taco Bell. Maybe their ads are nefarious enough that it’s our duty, as consumers, to revolt.

In the past two days, I have done an outrageous amount of reporting, but there is still one thing left to try. The suit specifies that Frank Siragusa’s allegedly inferior item was purchased at a Taco Bell in Ridgewood, Queens. Maybe that’s the reason I’m still a skeptic of the lawsuit—that the legally actionable understuffing could be isolated to that particular store.

As it happens, I used to live in Ridgewood, so I know the two Taco Bells nearby—and to determine which of them Siragusa patronizes, I email the lawyers listed on the suit. It’s the store on Myrtle Avenue, one quickly replies. That’s invigorating news. Now, I must make a ludicrous request: Which of my New York friends is willing to go to Siragusa’s Taco Bell, purchase a Crunchwrap, cut it in half, take pictures, and measure its height? I find a volunteer in Ashley Tobias, my upstairs neighbor of yore, who trudges five blocks to Myrtle Avenue, brings home a Crunchwrap, and dissects it per my request.

In sum, the Myrtle Avenue store does not seem to be a bad apple: Ashley’s Crunchwrap is roughly equivalent to mine, with one side measuring 3/4 of an inch, the other side one inch exactly. So this Crunchwrap—from the allegedly problematic Taco Bell—may actually have more filling than the (perfectly adequate) Crunchwrap that I received in Rockville. That’s a twist.

Just to be sure, I ask Ashley if it would be appropriate to sue over the size of her Crunchwrap. Her answer is no. “The ad did make it look double the size of what I got,” she texts—but she believes that’s normal for fast food.

So where, I must ask, does this leave us? Nobody is satisfied with their Crunchwraps—not me, not Ashley, not the various members of our families. But nor do we feel compelled to sue. The results of my inquiry are inconclusive. I have no idea what is right.

Perhaps we are a flock of sheeple, contentedly chewing our skimpy Crunchwrap cud, staring dead-eyed at the register while Taco Bell dupes us, pilfering our precious cash. In doubting the merits of the lawsuit, perhaps we are class traitors—accidental apologists for rampant corporate theft. But the prosaic reality is that I cannot imagine suing a restaurant unless they literally killed me. Maybe not even then.

I would posit that what’s happened at Taco Bell is not deception, but a classic human dilemma: a clash between our impossible dreams and meager realities. In this life, we are—each of us—relentlessly served the skinny Crunchwrap while expecting it to look like the ad. That feeling is devastating. It stalks us at night. But this agony cannot be solved by the courts.

Additional reporting by Ashley, Sage, and Oscar Tobias at the Myrtle Avenue Taco Bell in Ridgewood, Queens.