Maybe you’ve seen this recent viral feud: A diner headed to the Boston restaurant Table said he became ill and was hospitalized ahead of his prix fixe reservation. When he was told the restaurant wouldn’t waive its $250 cancellation fee, he disputed the charge with his bank, given his credit card’s travel-insurance policy. Then the restaurant’s owner messaged him on Instagram “to personally thank you for screwing over my restaurant and my staff.” The diner posted the rant and his response on Twitter, where it has been viewed nearly 25 million times, setting off a hot debate about cancellation fees.

These fees have become fairly ubiquitous in recent years as restaurants try to combat the plague of no-shows. An unexpectedly empty seat isn’t just a revenue hit for restaurants—it means servers lose tips and food goes to waste. The charges have also become very expensive for diners: High-end restaurants are increasingly treating dinner like a concert or sporting event, where you buy a nonrefundable ticket for the full price of your meal in advance.

For some diners already fed up with high prices, service fees, and subpar service, it’s one more way the hospitality industry feels less hospitable these days. Lawyer Eric Jeffrey has stopped making reservations at restaurants with cancellation fees on principle, and he diverted plans for a special-occasion dinner with his wife at 2941 in Falls Church because of its fee. The 70-year-old has never actually been charged for missing a reservation and isn’t the type to bail at the last minute, but he finds the policy uninviting. “It does cause people to feel less able to go—and less wanted,” he says.

Pineapple & Pearls has one of the strictest policies on paper: You pay the full price of dinner in advance—$925 for two, including tax and service fees—with no cancellations or rebookings allowed within 30 days. (You can, however, transfer the reservation to someone else.) Because of the high price and special-occasion nature of the fine-dining restaurant, owner Aaron Silverman says it’s difficult to refill empty seats within a month: “It’s a simple mathematical equation, right? The less people that show up, the higher the price has to be.”

When, if ever, to waive the policy is the “eternal question,” Silverman says. “There are crazy things that happen that are no one’s fault. But there are also a lot of crazy people who take advantage of that and aren’t telling the truth. And there’s no way to determine who’s who.”

Still, the reality is that many restaurants will refund or rebook if you call in advance with a reasonable excuse and a gracious attitude. “If you’re sick and we can accommodate, by all means, I’ll eat it,” says Causa owner Carlos Delgado, who charges the full price of his Peruvian tasting menu upfront ($467 for two), with a seven-day no-cancel period. He’s less tolerant of excuses like getting the date wrong.

Causa has ultimately charged for cancellations only a few times, usually involving diners who backed out within hours of dinner or showed up so late that they interfered with the next seating. The fees can lead customers to get nasty. “They talk to me in my face,” Delgado says. “They feel the empowerment because they’ve already paid for something.”

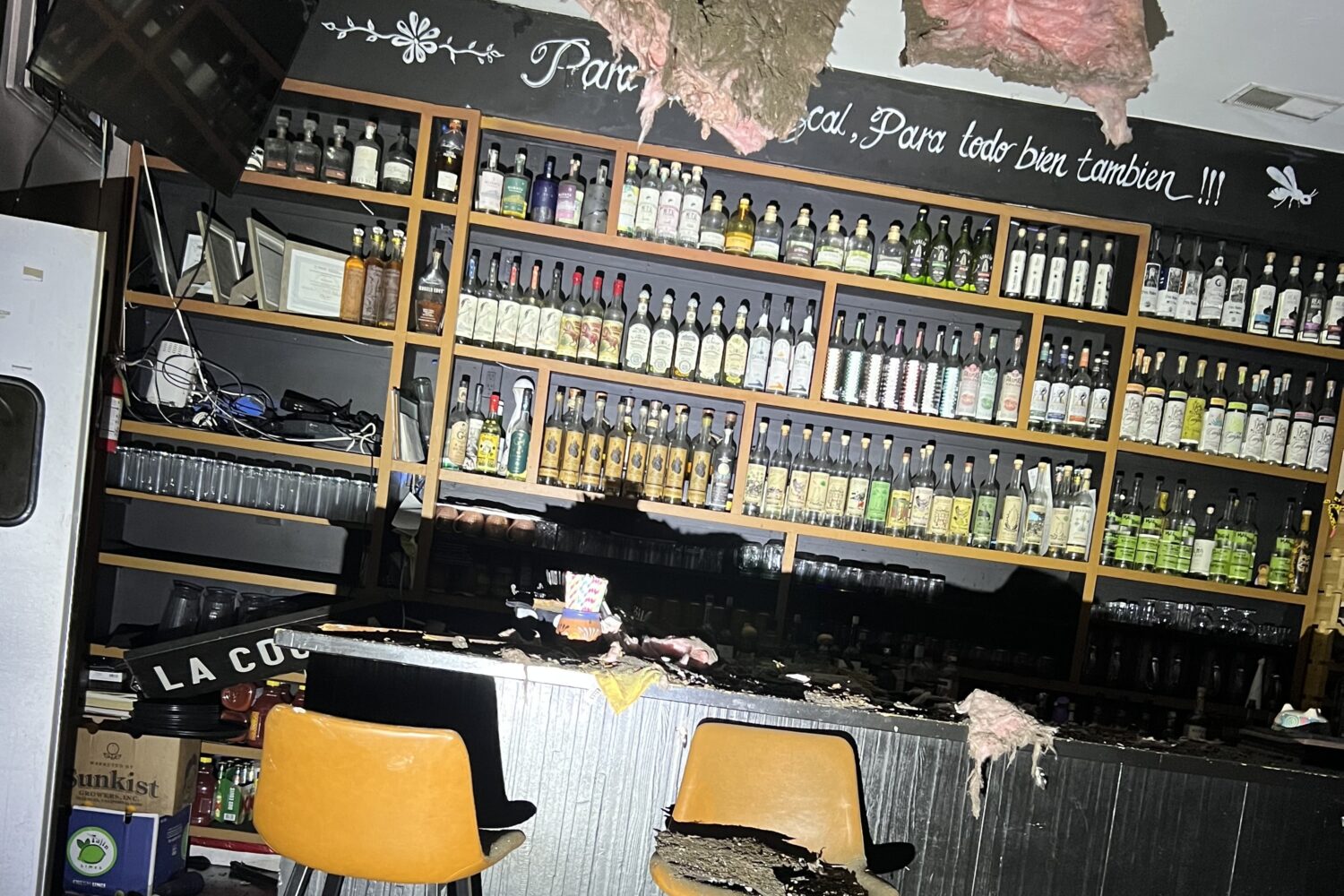

Ezequiel Vázquez-Ger, co-owner of Seven Reasons Group, recently encountered blackmail over a cancellation fee. A would-be diner threatened to write several online reviews saying she got food poisoning if they didn’t refund her money. He posted her message publicly on Instagram. “Some people call in advance to let us know they won’t be able to come, and we always refund those,” Vázquez-Ger says. “Then there’s always one outlier that sends a threat saying they will sue us or give us a one-star review if we don’t give them their money back.”

There are also people who dispute the cancellation charge on their credit card. Kirsten Fiery, service director at Amparo Fondita, says the Dupont restaurant gets hit with a “dispute fee” from banks when customers contest their $30 same-day cancellation fee or $45 no-show charge. Amassing too many returned charges can affect the business’s credit. Despite the fact that the policy is clearly stated when a reservation is made, she says fighting with the bank can be futile: “The first time I ever did it, it was denied, which made it feel like it wasn’t even worth disputing further. They always side with the customer.”

This article appears in the May 2024 issue of Washingtonian.