Contents

In February, DC drag artist King Molasses performed on one of the drag world’s most important stages: RuPaul’s Drag Race winner Sasha Velour’s NightGowns revue in New York City. Lip-synching in part to a monologue from Afrobeat pioneer Fela Kuti, Molasses put on a show radiating grief, tenderness, and pride, expressed through a jerky, swaggering striptease, all while wearing a giant fake beard, cowboy hat (eventually flung into the audience), and cowboy boots.

Molasses, who grew up in Prince George’s County, has been performing since 2018 and is a celebrated artist on par with the country’s best. But as a drag king, they often come into shows with “the understanding that there’s going to be people that (a) have no idea who I am or (b) have no idea what I do.”

An art form with deep Washington roots going back to at least the late 1800s, drag is having a complex cultural moment: more visible and mainstream than ever, but also facing a backlash that includes anti-drag ordinances in politically conservative areas and drag events nationwide enduring protests and bomb threats. Meanwhile, drag kings—traditionally defined as assigned-female-at-birth people performing in masculine outfits—remain largely in the shadow of drag queens. Despite fan requests, RuPaul has never included a drag king on his show, closing off a crucial avenue to fame and success. Even here in the DC area, kings report being booked and paid less than queens.

This is a loss for artists, but also for audiences. Gender-bending entertainers in masculine attire have been strutting across stages for centuries. The “male impersonator” was a staple of British music halls and Harlem cabarets, and one of the best-known performers of the 1950s and ’60s, Stormé DeLarverie, is said to have helped launch the modern LGBTQ+ rights movement by fighting back against police violence at New York’s Stonewall Inn in 1969. Perhaps because they’re still overlooked by the mainstream, today’s kings have retained all the ferocity, experimentation, and occasional sheer absurdity that make drag, well, drag. “Drag kings are still so underground, we are all able to define it for ourselves,” says Ricky Rosé, another prominent local drag artist.

DC’s kings are creating eclectic personas that range from otherworldly demons to get-you-pregnant-with-a-stare lotharios. At shows, you’ll see Hollywood glamour kings shrugging off their fake-fur coats to 1930s show tunes, goofy kings lip-synching to Radiohead in Muppet costumes, and gender-bendy goth kings twerking in glitter beards. Performances are raucous and liberating: Audience members fling dollar bills while kings stalk the room, seducing onlookers.

Here are eight artists who represent the local scene.

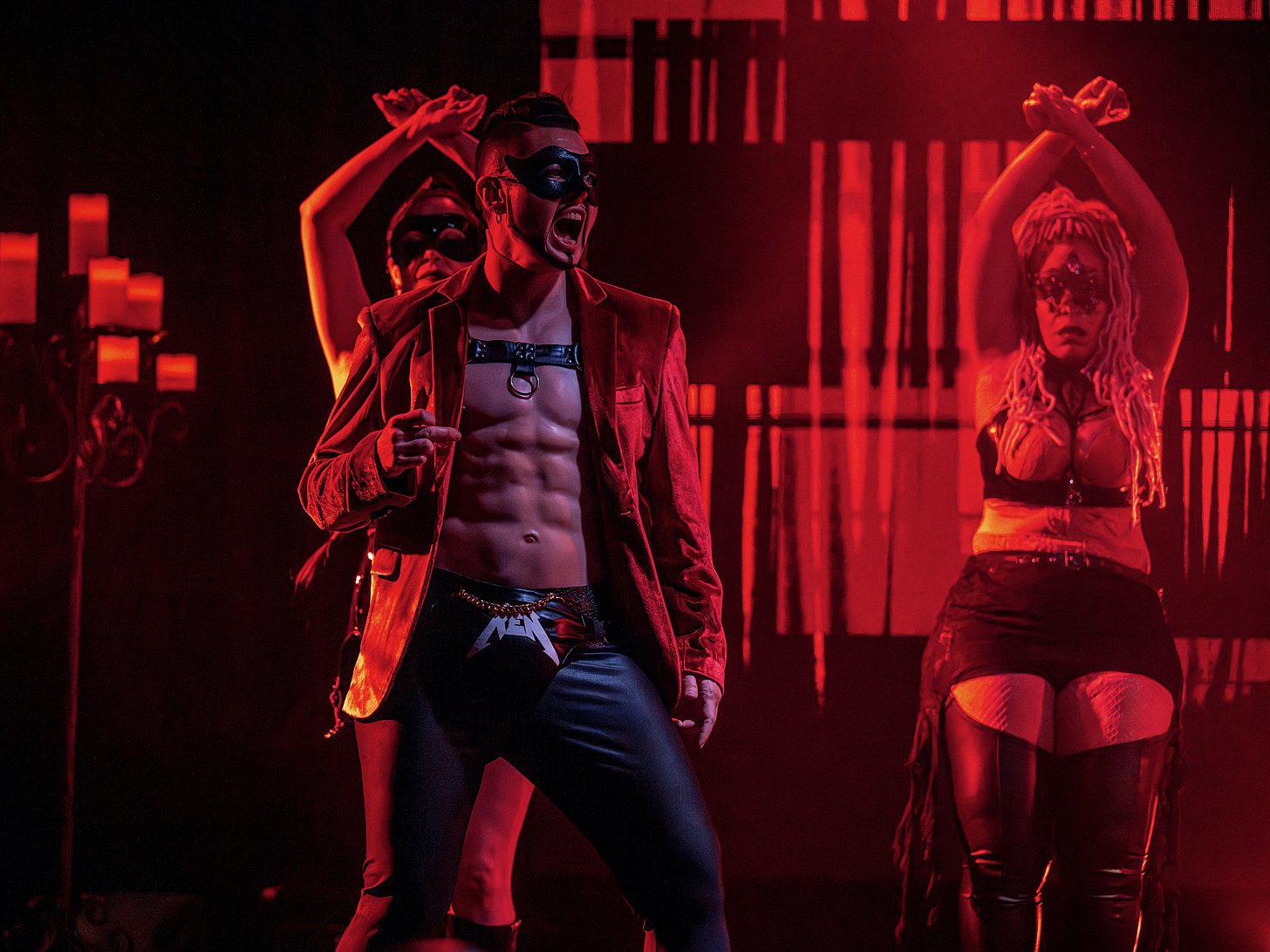

Blaq Dinamyte

Dinamyte says he has “always been a performer,” starting when he was seven in church groups and continuing through college at the University of Maryland, where he appeared in gender-swapped versions of The Rocky Horror Picture Show and Othello. After Shakespeare, he says, drag felt easy: “I was like, ‘I can just lip-synch these songs and wear clothes that I already wear to work? This is win-win, it’s all cream after that.’ ” Dinamyte has performed at the Kennedy Center and Dance Place, among other venues, showcasing a persona influenced in part by blaxploitation films, Red Hot Chili Peppers frontman Anthony Kiedis, and musician Lenny Kravitz.

Baphomette

Baphomette describes his general vibe as “glam-rock demon.” His performances range from femme drag with neon wigs and horns to pajama-clad, mustachioed Old Hollywood kings to a costume inspired by Pinhead from the Hellraiser horror-film series, featuring the syringes Baphomette uses to administer his gender-affirming hormones. (The performer later reassured his Instagram followers that the needles were “dulled and sanitized.”) “You get a lot of weird looks as a trans person,” he says. “When I started drag, I was like, ‘Okay, I’m going to make people give me weird looks on my terms now.’ ”

Dirty Sanchez

Sanchez describes his persona as “some dirty dude who’s Western, kind of sleazy,” but also “love[s] femininity so much.” He can spend up to two hours just on makeup: glittery lips, exaggerated cheek contouring, and bright eye shadow. Onstage, he says with a laugh, “I black out and I’m possessed by the spirit.” Usually dancing to Reggaeton—“I don’t really do slower songs”—he works his way around rooms, looking to connect with audience members. “Whoever’s giving me a dollar, I’ll make sure they get their moment,” he says. “Whoever is really into it, that’s who I’m like, ‘Yes, I did this for you!’ ”

Ken Vegas

Vegas first produced a show exclusively featuring drag kings in 1999 at now-shuttered Club Chaos. “It was so successful that there was a line up the stairs, around the block,” he says. He subsequently created the DC Kings, the city’s first king-centered troupe, which at its peak was putting on three shows a month. The group disbanded in 2015, but Vegas can still be seen doing “dark and sultry” performances—there’s lots of leather, and he’s often joined by his wife, a belly dancer with a penchant for swords—at a regular goth night in Arlington. “Which is cool for me,” he says, “because I never had a place to do the Cure or the Smiths.”

Pretty Rik E

In 2016, Rik E, best friend Chris Jay, and burlesque performer Lexie Starre created Pretty Boi Drag, a troupe designed to support and promote drag kings of color. Performing in DC and nationally, Pretty Boi Drag also hosts regular “Drag King 101” events to help would-be kings get their sea legs. Participants learn about the history and theory of drag and get a “one-hour hands-on beard tutorial.” They also receive a “drag kit” consisting of makeup and brushes, synthetic hair for beards, and a custom PBD makeup bag. “The part that I like the most,” Rik E says of his mentorship role, “is watching people go from this timid newborn baby deer to a full-on, ten-point buck.”

Ricky Rosé

“I am such an introvert and autistic as hell and everything,” Rosé says. “But truly the second that song starts when I get onstage, I completely transform.” Rosé’s gender-fluid drag performances have won them many plaudits, including DC’s Best Drag King in 2019 and Mr. Trans Puerto Rico in 2023. They say that while backlash against drag is “scary,” the best way to handle negativity and threats is through continuing to live their life in public: “The only way to combat [hate] is to remain hyper-visible and gain power in numbers from inspiring others to join our ranks and support us.”

Roman Noodle

Noodle, who tags himself “your future baby daddy,” went to a “Drag King 101” event during a difficult period of addiction and self-harm and is now a Pretty Boi Drag regular. His day-of-show routine is well practiced: “Shower, gotta put the baby oil on, everywhere except for the top, because I tape,” he says, describing a binding process some kings use to flatten their chests. “And then I go ahead and do my face. I use mascara for the eyebrows, I do mascara for my mustache as well.” As for creating the rest of his persona’s facial hair? That’s more idiosyncratic. When Noodle gets his hair cut, he says, he’ll save the clippings and “use it to tack on a chin strap.”

King Molasses

When Molasses first saw a Pretty Boi Drag show at the Bier Baron in Dupont Circle in 2016, they “got chills, like it kind of went quiet. And I just remember this feeling of telling myself, like, ‘I would be really good at this.’ ” As a child, Molasses emotionally and mentally withdrew in order to cope with bullying, family conflict, and their father’s extended illness. Through performing, they’ve been able to dial down their anxiety and achieve a new sense of ease in their body—helping Molasses connect with their father before his death and survive the grief after: “Drag really did bring me to spirit.”

This article appears in the June 2024 issue of Washingtonian.