It figures that the International Spy Museum’s surplus artifacts would sit inconspicuously in a quiet corner of the fourth floor, just barely separated from the throngs of day-campers and summer tourists crowding the neighboring exhibits. The collection of undisplayed items marks a highly anticipated triumph for curators, who refer to the remodeled gallery space as “The Vault.”

Developing an on-site archive was a major goal of the museum’s 2019 move from Penn Quarter to L’Enfant Plaza. Previously, the collection had been housed in long-term storage, which made it difficult to access. “It came on site in 2020 as a necessity during the pandemic, and then kind of sat there,” says Laura Hicken, the museum’s collections manager. “And starting in 2022, we really started this project of formalizing this space as where our collection would live.”

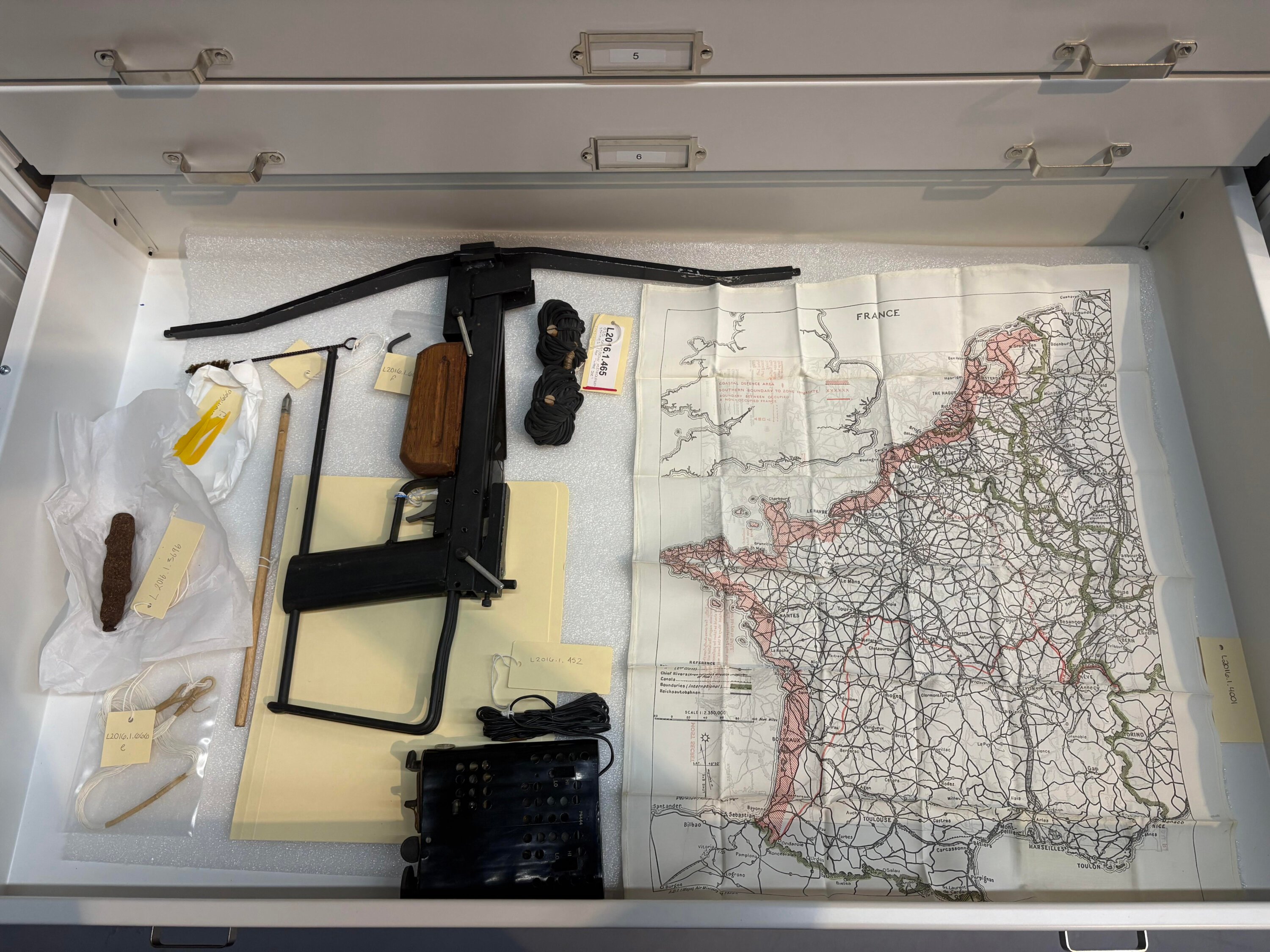

And there’s quite a roster to keep track of. The museum’s artifact count tripled in 2017, when historian and prolific collector H. Keith Melton donated more than 5,000 items from his personal trove. Hicken estimates that there are between 10,000 and 11,000 artifacts in the Vault today. Her team is currently taking inventory of everything they have; they’re through about 7,000 objects so far and hope to be done by the end of the year. They’re still finding objects they didn’t even realize they had.

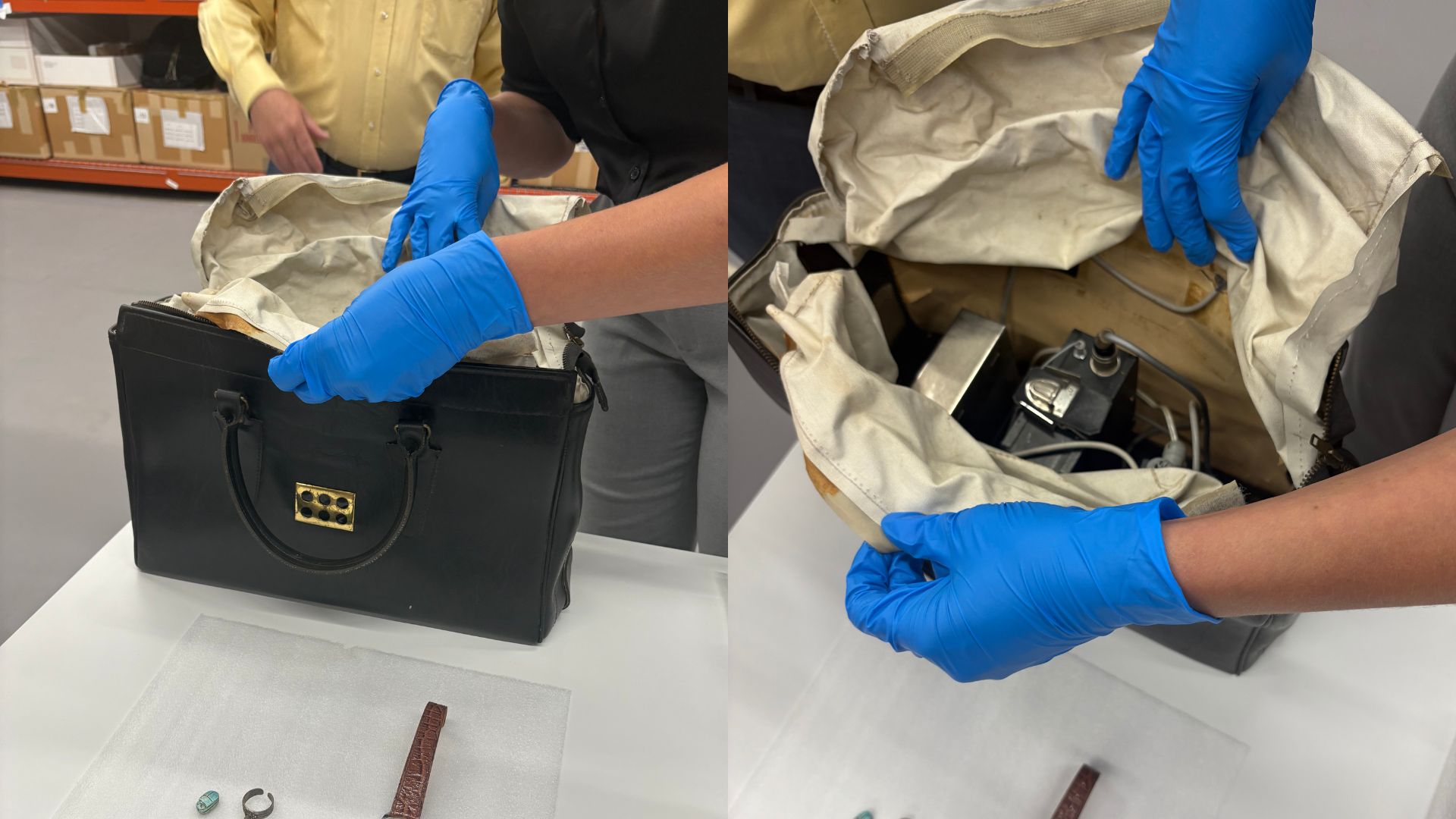

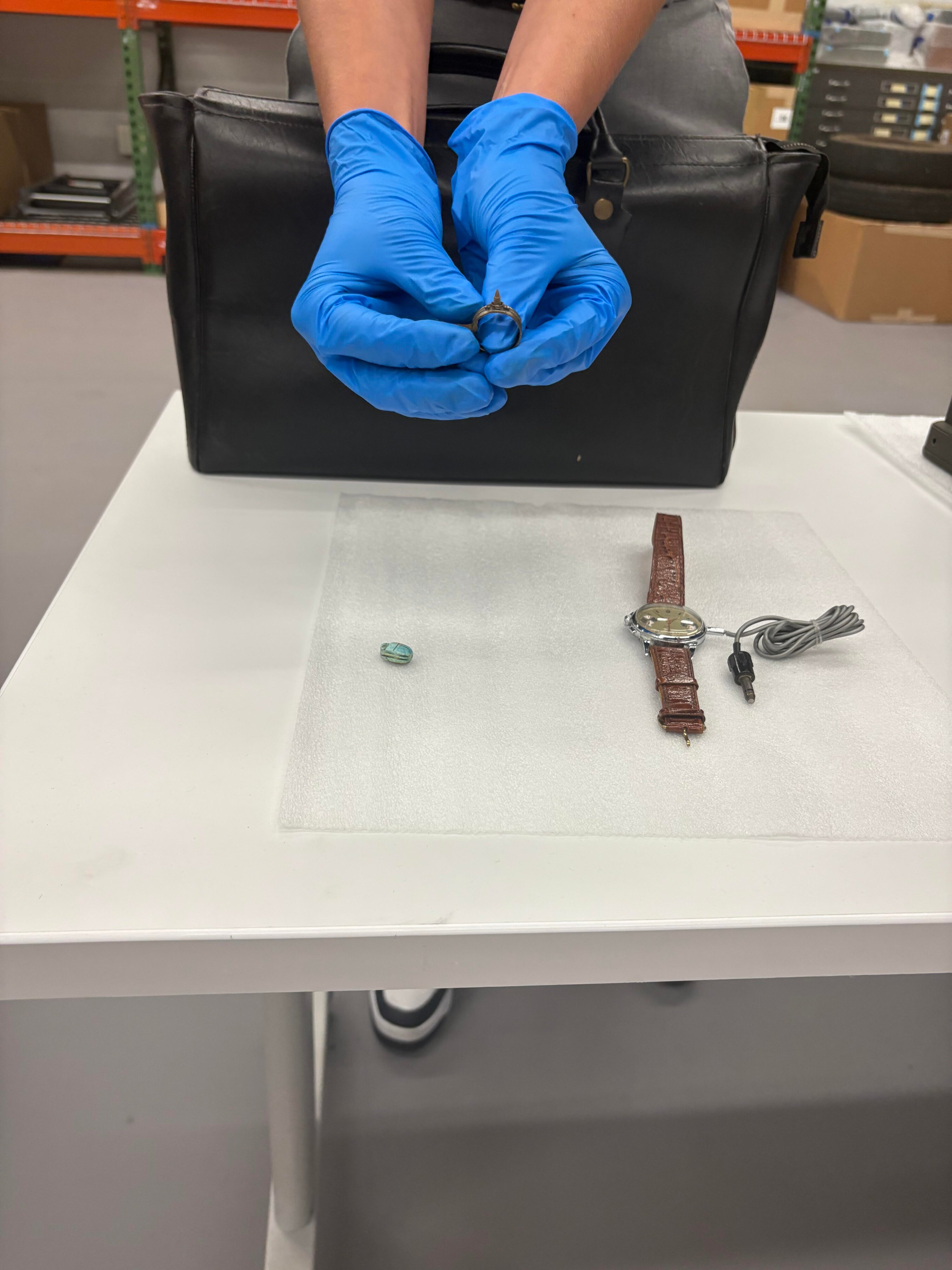

What might this elusive heap of espionage-related memorabilia consist of? As you might expect, much of it isn’t particularly riveting at first glance. “A good spy blends in, so they thrive in the mundane. So much of our collection is like, ‘Oh, this is just a briefcase that everybody carried in the ’80s,'” Hicken says. “And it’s not that interesting until you open it up and see that there’s a camera in it.”

Still, the Vault does house a number of more on-the-nose relics. One of Hicken’s favorites is the Welbike—a comically tiny motorcycle that was mass-produced by the British for use by the Special Operations Executive during World War II. The bike, which folds up, would be dropped into war zones to help saboteurs and spies make quick escapes. “It’s very cute, but it also represents the desperation of people trying to escape behind enemy lines, that you would be willing to ride this very small, uncomfortable motorcycle if that was your only option,” Hicken says.

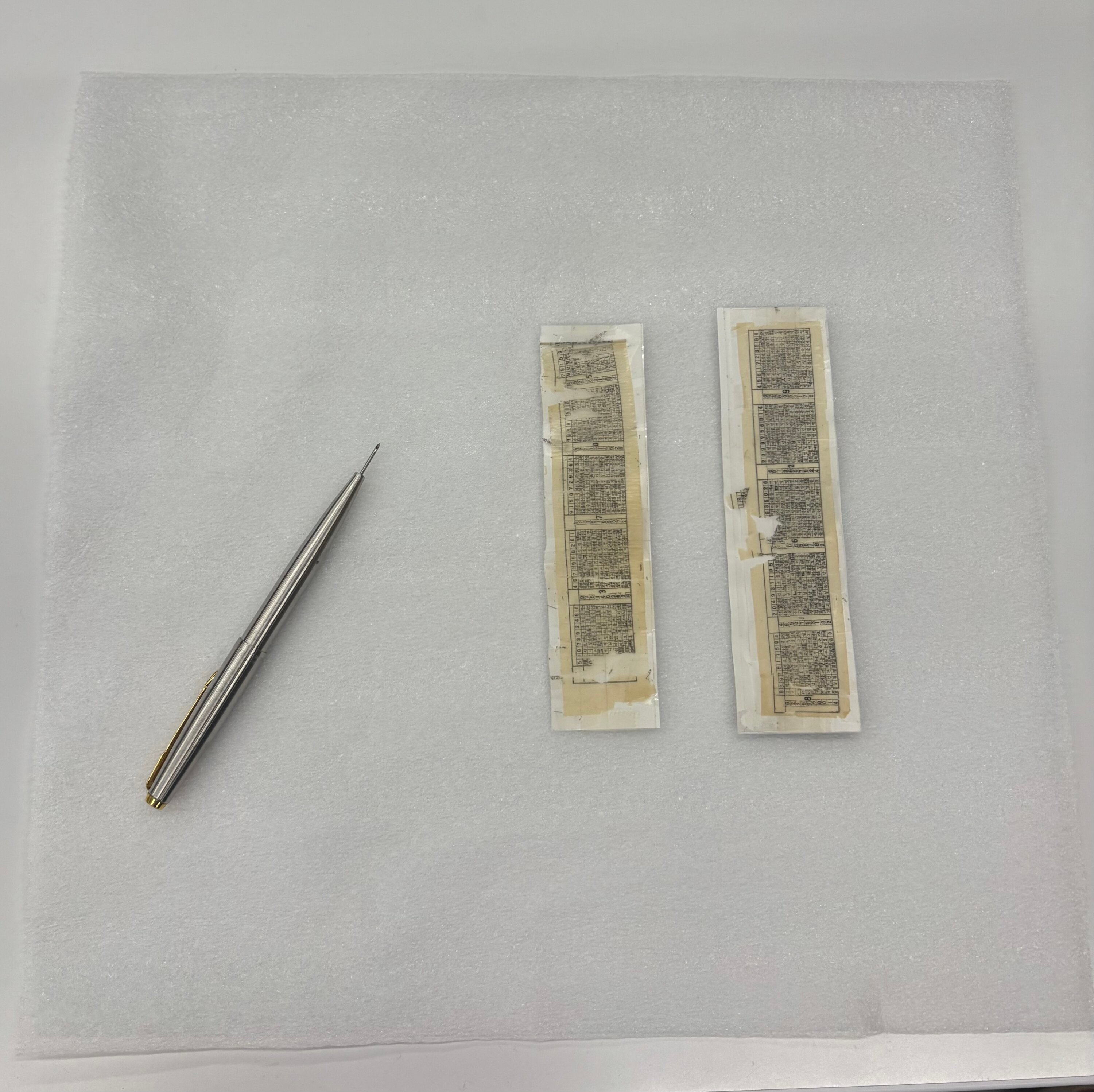

Unsurprisingly, the museum lacks a bit in 21st-century artifacts. “Most of today’s best spies, we’ll find out about in, like, 50 years,” as Hicken puts it. But there are a few relatively contemporary items, including a couple of items on loan from the South Korean embassy: a circa-1997 one-time pad and a pen that clicks into a paralytic-filled needle, which was seized off a North Korean assassin in 2011.

To accommodate the fragility of the collection’s vintage possessions, the Vault is temperature-controlled (I’d nominate it as a contender for the best air conditioning in the city) and guarded against pests. Collectors are also working on acquiring pH-neutral storage boxes. The ability to check on very old, very delicate artifacts—particularly textiles, including several that date back more than 100 years to the Russian Revolution—is another benefit of having an on-site archive.

Some archival items will find their way into exhibits. “The hope is that now that we can get to it, it will be rotated into the displays,” Hicken says. “We’ve already had some of that. We’ve done some little swaps. And especially now that the museum has been open for five years, there are things we want to both swap out and refresh for content reasons.” Plus, paper and fabric artifacts currently on display could use some downtime outside the public eye to maintain their condition.

The Vault itself won’t be open to the public, but it offers a new host of options for curators to fold into existing exhibits. The plan is to equip the room with plenty of lighting, so visitors can “peek in” through the glass doors to catch a glimpse of what’s inside. The museum also plans to develop a digital interactive exhibit that allows website users to browse through the collection. “The things in our museum, you weren’t supposed to see—it’s not a painting, it’s not a sculpture, it wasn’t intended to be on display,” Hicken says. “And so we are taking the things that were always meant to be in the shadows, and we are shedding light on them.”