One of my most enduring memories is of riding through the Southern Maryland countryside on Saturday afternoons with my mother and father—my father at the wheel, all of us in hot pursuit of the smell of barbecue. My father loved ribs and thought nothing of getting in the car and driving an hour and a half from our house in Greenbelt to Charles County to find them. The names of the places have faded from memory but not the images: the aromatic smoke curling above the ramshackle white houses, the three of us at a picnic table, licking our fingers or wiping them on the slices of white bread that came with an order, the flies buzzing about our heads.

My father loved these kinds of afternoons. Loved the quest. Lighting out for a destination, not knowing what you’d find, hoping for the best. And even if it was lousy, which sometimes it was, coming home with a good story.

Most of the friends I grew up with didn’t venture beyond meat and potatoes, spaghetti, and macaroni and cheese, but that wasn’t my experience. We ate everything. Thai and Spanish and French and German and Japanese and Vietnamese and Indian and Greek. My father loved the stuffed grape leaves at Ikaros in Baltimore, so I wanted to love them, too. He was the one who turned me on to pupusas. He introduced me to bul goki and crepes, to hot-and-sour soup and the pleasures of hot pot.

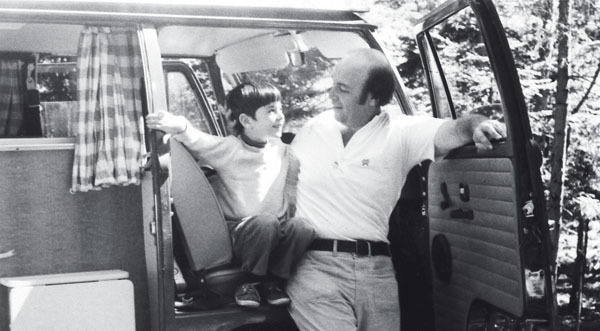

So long as a restaurant had character, had soul, he loved it. Dives, taverns, pubs, it didn’t matter—good was good. His mother scolded him, repeatedly, for taking a ten-year-old to a bar, but my father never listened. I spent many a Saturday night in the late, lamented Henkel’s—hard by the railroad tracks in Fort Meade and probably once a bordello—chowing down on a Chenkelburger as my father and mother worked their way through the foot-high ham sandwiches and knocked back bottles of beer.

The other dive he loved was the Irish Pub in Baltimore. In the summers of 1977 and ’78, I could have gone to camp, but I chose to stay home. Instead of archery and swimming, I spent a few days every week in my father’s light-filled studio, drawing quietly by myself in a corner as he worked on his towering canvases. Every other week, we went to the Irish Pub for the magnificent cheeseburgers, thick and oozing juice.

You don’t realize the imprint these things make on you, don’t realize you’re merely picking up a long thread that has been left for you, until you gain some distance on your past.

When I was in graduate school in Virginia in the early ’90s, I discovered a pool hall and bar whose owner devised a special menu every Friday afternoon to feature the cooking of his grandmother. Seven bucks got you a thick slice of grilled meatloaf—you could see slices of garlic and bits of thyme in the meat—skin-on mashed potatoes, gravy, and beans. I went back to campus and told my friends, who all said: That dump?

I called my father, who I knew would understand. He said, “Sounds terrific! When are we gonna go?”

I came to writing about food after having written about seemingly everything else—sports, media, politics, books. When someone would ask me how I’d gotten into food writing, I’d say I had sort of stumbled into it. But the truth was I’d been preparing since I was a little boy.

My father got a kick out of my being a food critic, and I loved taking him out to eat with me. We went everywhere. It was a new chapter in our eating adventures.

He made no distinctions between a refined restaurant and a casual spot, and he paid no mind to reputation or buzz. As an artist, he craved his solitude, which he needed in order to think and create, and he could be irascible if he didn’t have long blocks in the day to work on his paintings and read and refill the well, as Hemingway put it. But after that, he longed for contact. He loved the energy of a good restaurant, the sense of possibility. Strangers coming together, blowing off steam, finding community, if only for a couple of hours. A good restaurant restored you, sent you on your way a new man.

Often, a hostess would show us to a table somewhat out of the way, presuming that a man in his seventies would be looking for a quiet spot. My father preferred to sit at the bar. Somehow, food was always better at the bar. The world looked better at the bar.

When he became sick, I was bewildered. It couldn’t be. Daddy? He had the energy of a 40-year-old. I had thought he was indestructible.

He couldn’t go out the way he used to, or as often, but food was still a salve. And still a part of our bond. The day he and my mother and I met with the surgeon to discuss the plan for his cancer treatment, I went out and got a deli tray—bagels, lox, whitefish. It had been a long and anxious couple of weeks, and most meals he just picked at his plate. But that night he ate with the old gusto.

Chemo and radiation had conspired to destroy what was left of his appetite. But somehow he always found room whenever I brought him a restaurant meal. I often thought I could save him through food.

One night, when he was at National Rehab Hospital after cancer surgery and an infection that sent him into the ICU for several weeks, I snuck in shrimp and grits from Vidalia plus corn muffins and lemon chess pie. It had been a long day of physical therapy, and he didn’t eat a lot. But that was okay. It was enough to see him nodding his head in appreciation, to see the simple contentment that crossed his face.

He got stronger, came out, learned to walk again. One day in May, he told me he wanted to go out again, wanted to accompany me on my dining rounds.

We covered the area. Virginia, Maryland, and DC. High end and low end. On trips to Artery 717, the Alexandria gallery where he was artist in residence last year, he dug into fried cod and chips at Eamonn’s and lunched on the egg-and-bacon salad at Restaurant Eve in the bar. He discovered Ethiopian and loved it. He slurped back bowls and bowls of pho. And of course there was barbecue.

He was in and out of the hospital through the summer and fall. And almost as soon as he was back home, he was ready to go to another restaurant. One day in December, I swung by the house to take him to lunch. He was sitting on the hospital bed in the living room with his coat on. “He’s been sitting in his coat for three hours,” my mom said.

I figured I’d take him someplace close by, something simple. He’d be checking into the hospital the next day for more surgery.

When we were in the car, he said, “Let’s go somewhere.”

“You sure? Are you up for it?”

“I’ve been looking forward to this all day,” he said. “Anywhere you want. Virginia—wherever. I’ve got all day.”

I took him to Present, a Vietnamese restaurant in Falls Church I had been to before and wanted to write about. It might not have been the sort of place he was drawn to—it didn’t have the noise and crackle he loved, but its serenity was comforting. And the menu’s admonishment to live in the moment—in the present—was oddly fitting.

He was stronger than he’d been. He’d gained 30 pounds since the chemo and radiation—most of it, my mother believed, from restaurant food. He didn’t eat much of her cooking anymore. I told him he had become the equivalent of a social drinker—a social eater.

We took our time, and we talked, and talked. He was worried about the surgery. He said he didn’t know if he’d make it this time. Our anxiety seemed to lift a little as we worked our way through the meal. He drank two Vietnamese coffees and took bites from every bowl and plate on the table. When we left 2½ hours later, the place was empty.

In the car, I asked if he wanted to hit somewhere else. “You’re kidding,” he said, giving me a long look. And then, the old adventurer: “Sure, why not?”

On second thought, I decided it was probably best to get back home. My mom was waiting for him. Another time.

For days, he talked about the meal and the coffee. He even talked about it in the hospital after his surgery. All of his nurses learned just how good the coffee was, how dark and rich, what a terrific time he’d had.

That afternoon in Falls Church turned out to be our last excursion. He was in the hospital for 61 days. He never did come out; there was no “another time.”

When he passed away in February, I lost more than my father, my best friend and mentor. I lost my restaurant partner. The adventure won’t ever be the same.

This article first appeared in the July 2009 issue of The Washingtonian. For more articles from that issue, click here.