In any of the homes where Bill Paley grew up—the 85-acre estate

in Manhasset, Long Island; the pied-à-terre at the St. Regis hotel in

Manhattan; the 20-room duplex with lacquered, taxicab-yellow walls on

Fifth Avenue; or the retreat in the Bahamas called Lightbourne House—you

would have found original works by famous artists on the walls. Maybe a

van Gogh or a Gauguin in the living room. A Matisse in the parlor. Even a

Picasso—a seven-foot-high Picasso, “Boy Leading a Horse,” from the

artist’s Rose Period—in, of all places, the entry hall.

As a kid, Paley couldn’t have told you much about the

masterpieces. “I didn’t realize what we had until I was older and started

going to museums,” says Paley, whose father, William, became a millionaire

at age 26 and had amassed a half-billion-dollar fortune by the time of his

death in 1990. “I’d be looking at a Rousseau and I’d say, ‘Hey, Dad has

one of those over the fireplace.’ ”

Stars of stage, screen, radio, and print were regularly feted

at the Paleys’ residences, none more regularly than Truman Capote. For two

decades, the author of Breakfast at Tiffany’s was a confidant of

Paley’s mother, Barbara Cushing Mortimer Paley—Babe for short. A socialite

and fashion editor at Vogue, Babe Paley was lauded for her

interior-design sense and personal style and was inducted into the

International Best Dressed List Hall of Fame in 1958 along with Hollywood

stars Claudette Colbert and Irene Dunne and Britain’s Queen Elizabeth II.

Capote once wrote of Babe, “Mrs. P. had only one fault: She was perfect;

otherwise, she was perfect.”

Even as a kid, Bill Paley could have told you that. “My mother

had amazing grace and amazing taste,” he says.

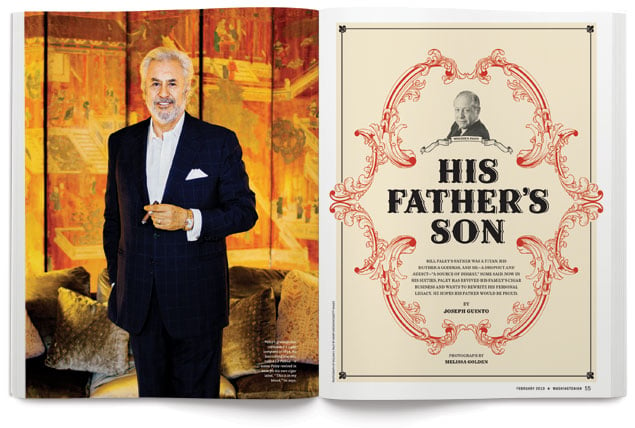

Paley, now 64, sits in a tobacco-brown leather chair in the

fern-green parlor of a Dupont Circle rowhouse he has owned and used as an

office since 1993. “All boys see their mother as a goddess,” he says. “But

when I looked around and saw that everyone else thought my mother was a

goddess, too—well, I really came to believe it was true.”

He pauses. There’s a “but” coming, a telling clarification:

“But she wasn’t the warmest person in the world. She had her own intimacy

issues, much like my father.”

• • •

If Babe was a goddess, Bill’s father, William S. Paley, was a

titan. In 1927, he cashed in his shares of his family’s booming cigar

business and bought a struggling network of radio stations known as the

Columbia Broadcasting System. By the time he left that network in 1983,

Paley had built it into a multibillion-dollar media corporation. CBS. The

Tiffany Network. In 1976, the New York Times wrote that William

Paley was to American broadcasting “as Carnegie was to steel, Ford to

automobiles, Luce to publishing, and Ruth to baseball. None has yet been

succeeded in kind.”

None. Certainly Bill Paley, William and Babe’s only son

together, hasn’t succeeded his father’s accomplishments. Little Bill, as

they once called him, could have followed his father into CBS’s executive

ranks. He could conceivably have run the network that remained in William

Paley’s control for decades. A twentysomething Bill Paley—at a

camera-ready six-foot-two, with midnight-black hair and what was once

described as a “toothpaste-ad smile”—might also have taken an on-air role

at the network. But he refused to be a part of CBS.

Instead, he grew his hair long, donned an earring that enraged

his father, bought a boat, and sailed the Florida Keys. He sometimes spent

weeks alone in the middle of the Everglades. He was, he says, “a hermit.”

He was also an addict. He picked up an amphetamine habit in Spain, heroin

in Vietnam, and plenty of marijuana in Northeast DC, where he ran a bar

called the Gandy Dancer.

When Bill Paley turned 27, the same age at which his father

took over CBS, he was described in print not as a titan but as “a hippie

and a dropout.” In the book CBS: Reflections in a Bloodshot Eye,

author Robert Metz also said Paley had been “a source of dismay” to his

father.

Thirty-eight years have passed since those words were written.

Long enough for both Babe, in 1978, and William, in 1990, to have passed

on. Long enough for Bill Paley to get married, get sober, have two sons of

his own, and spend two decades as a drug counselor working for people he

understood as well as anyone—the rich, famous, and addled.

But 38 years isn’t long enough for Bill Paley to feel he has

left his own imprint on the Paley name. Not yet, anyway—though that may be

changing.

In 2010, Paley launched La Palina cigars, renewing the

trademark on a brand that was originated in 1896 by his grandfather, Sam,

and his great-uncle, Jacob, immigrants from the Ukraine. La Palina made

the Paleys rich—rich enough to buy CBS. And CBS in turn made them rich

enough to abandon La Palina. That happened a long time ago, too, be-fore a

15-year-old Bill Paley smoked his first cigar, a Cuban-made Montecristo

No. 2 that his father handed him at Lightbourne House.

“He wanted to see if I’d turn green,” Paley recalls. “And I

did.”

Now, by bringing La Palina back, Bill Paley is hoping to turn

his family’s legacy into his personal legacy—one that won’t be stamped

with “a hippie and a dropout” but will read simply: “Est.

1896.”

• • •

Babe and Pasha and Goldie lie at rest, encased in wooden boxes

with shining, golden trim. These are Bill Paley’s family members—or at

least the cigars he named after them (Pasha was his father’s nickname)—and

they’re on display at downtown DC’s W. Curtis Draper Tobacconist, a

125-year-old purveyor of premium tobacco products, one of the last vices

that official Washington still openly tolerates, albeit not as openly as

it once did.

Bill Paley, who first moved to Washington in 1970 at age 21,

has been buying cigars from Draper’s for a couple decades. And with the La

Palina company he started in 2010, he’s also now selling to Draper’s two

stores and to Civil Cigar Lounge, a Draper’s offshoot that just opened in

Chevy Chase Pavilion.

“We get producers from all over the world in here,” says

Draper’s co-owner John Anderson. “But they come in with an appointment.

With Bill, we just walk in and he’ll already be here talking to someone

about his cigars.”

For Paley, that often means talking about his family. “If I

didn’t have the La Palina story to tell,” he says, “I would have been just

another schmo trying to make his own cigars. Having the story of reviving

this brand was content. And I knew content would be news. So I crafted a

great story around it. ”

Actually, he didn’t need to do much crafting. The story was

great from the beginning. And the beginning is in the late 1880s, when

Samuel Paley—a newly arrived immigrant from Brovary, a Ukrainian town

outside Kiev—took a job in a Chicago cigar factory. He worked as a lector,

meaning he read books and newspapers and whatever else to the guys rolling

cigars. Most of the rollers were probably Spanish speakers, so you have to

figure they didn’t understand the Ukrainian very well. But, still, any

distraction must have been welcome because rolling cigars is a tedious

business. You take a bundle of small leaves, wrap them in a bigger leaf,

roll another big leaf around that, stick the edges together with vegetable

gum, and cut an end off. Then repeat.

That’s how premium cigars are still made, La Palina included.

“More than 300 hands touch a cigar between the seed and the store,” Bill

Paley says. “I love the idea of producing something handmade that involves

a series of artisans and experts. It fits in very well with my idea of the

good life and of surrounding yourself with objects that have intrinsic

value. It’s also especially wonderful to have an object of intrinsic worth

that you immediately destroy.”

• • •

Maybe Sam Paley felt the same way about cigars. But that seems

unlikely. For him, cigars were business. In 1896, Sam and his brother

Jacob opened the Congress Cigar Company, which made and sold many brands,

primarily one called La Palina. “That’s what the workers called my

grandmother Goldie,” Bill Paley says. “La Palina is a feminized form of

the name Paley.”

A few years later, Sam and Jacob moved the business from

Chicago to Philadelphia, where they built it into a giant. By 1926,

Congress Cigar had seven factories in four states, employing 4,500 people

and producing 255 million cigars a year—nearly 700,000 a day.

The Paleys experimented with promoting La Palina on the radio,

a medium still in its infancy. The ads worked. After the Paleys paid

$6,500 a week to back a show on WCAU in Philadelphia called The La

Palina Hour, sales shot up by 150 percent. That success helped

convince Congress Cigar’s director of marketing, Sam Paley’s son, William,

that commercial radio had huge potential—bigger than cigars. So in 1928,

at age 26, he invested nearly half his fortune—$417,000, with Sam and

Jacob throwing in another $86,000—in the Columbia Broadcasting System, a

network of 16 stations that included WCAU. Soon thereafter, William moved

to New York City to run CBS. He wouldn’t relinquish that role until 1983,

when he was 82.

But he did give up his stake in Congress Cigar. So, too, did

Sam Paley, who joined the board at CBS in the 1930s. Bill Paley has tried

to investigate what happened to the La Palina brand after that. The trail

is cold. William Paley rarely spoke of business around his children, and

Sam Paley never talked about the cigar business at all.

“I had no association of my grandfather and cigars,” Bill Paley

says, adjusting the popped collar on his purple polo shirt. “I just know

that sometime about 1960 the La Palina brand faded away.”

It would have stayed that way, a footnote to the story of CBS,

except that one day in 2005 while luxuriating at Lightbourne House—which

he bought from his father’s estate after inheriting a reported $30

million—Bill Paley decided it might be nice to have a cigar custom-made

for him and his guests. Not just any cigar. A great cigar. The best he

could have made.

“For Bill, his cigars are really a personal creation,” says

George Hemphill, owner of Hemphill Fine Arts in DC’s Logan Circle

neighborhood and one of Paley’s longtime friends. “He wants them to be

works of art.”

It took three years before Paley decided that his house cigars

should also be a business. He believed that, working with the top Bahamian

cigar manufacturers, he could produce a high-quality product. And by 2008,

he knew he could get the La Palina trademark back. But could he actually

sell cigars to the public? Of that, he wasn’t so sure: “I thought, ‘You

know, making cigars is really an ego project. Why should I be doing that?’

Then I had an epiphany: ‘Well, I have all the right in the world to make

cigars. This is in my blood.’ ”

Frank Langella was wonderfully stern playing William S. Paley

in Good Night, and Good Luck, the George Clooney-directed movie

about Edward R. Murrow. And, as Babe Paley in Infamous—the biopic

that foolishly followed Philip Seymour Hoffman’s Oscar-winning title role

in Capote—Sigourney Weaver was long and lovely and almost always

seen with a Bakelite cigarette holder in hand.

So far, Bill Paley hasn’t turned up as a character in any

films. He did help make a movie, though. He was a production assistant on

A Talent for Loving, an independent Western comedy that lacked

both laughs and an audience.

Paley went to work on A Talent for Loving for three

months just after dropping out of Rollins College in Florida. “I did

dreadfully in school,” he says. “My cerebral and emotional development was

late. But then again, I was in the Army at 19.”

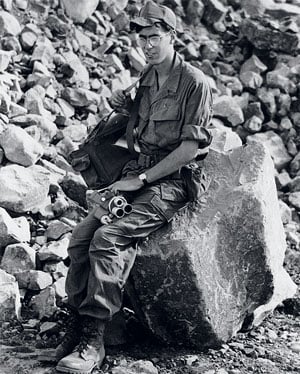

In 1968, he was drafted for service in Vietnam, but he enlisted

before being called up for duty so that he could secure an assignment

especially suited to his skills: motion-picture photographer for the Army.

He was stationed at Long Binh, the largest Army base in Vietnam. Half of

his time was in the field. The other half wasn’t.

“I shot a lot of medal ceremonies and marches,” he says,

laughing. “As anyone will tell you, war is an extraordinarily boring time

interspersed with short periods of intense panic.”

In a 1977 Washington Post profile headlined a famous

father’s son lives out of the public ‘eye,’ Paley confessed that he had

dealt with both the boredom and the panic of war by indulging in heroin.

“I’d been a user since I was a teenager,” Paley says today, lowering his

already soft voice to a confessional level. On the movie shoot in Spain,

he’d gotten hooked on amphetamines. And before Vietnam, he also spent time

in Morocco, where, he said in the Post article, the hashish was

“lovely.”

William Paley, his father, was already looking for a successor

the year his son returned to the US. The elder Paley was 69, his son 21.

William didn’t control enough CBS stock to name just any successor he

wanted, much less a college dropout. CBS, after all, wasn’t a cigar store.

But he could have placed his son Bill in any number of jobs. Such as the

one Paley’s half-brother, Stanley Mortimer, had working with his

stepfather in a perfume business initially founded by Babe Paley. (In

addition to Bill and daughter Kate, William Paley had two adopted children

from his first marriage to Dorothy Hart Hearst and two stepchildren from

Babe Paley’s earlier marriage to Stanley Mortimer.) But Bill Paley wasn’t

interested in pursuing any of the paths his father could have laid out for

him.

“After Vietnam,” he says, “I wanted to take a break from

anything I had ever done before.”

Think about that for a moment: Paley had grown up in an

exclusive Long Island community. He had been to boarding school in

Switzerland. He had taken European vacations with his family, eating in

the temples of haute cuisine with his father. He wanted to take a break

from that? Or, knowing it was already too late to become heir of the CBS

chairman’s seat, did he really just want to run away and hide?

• • •

After he was discharged from the Army, Bill Paley put a gold

hoop in his left ear, grew his hair to shoulder length, and moved to Piney

Point, Maryland, on the Chesapeake Bay. He would spend the next half

decade on or near the water. In Piney Point, he restored a dilapidated

57-foot sailboat, then sailed it to Florida and traded it in for a 1930s

gaff-rig schooner. For three years, he sailed that boat around the Florida

Keys, working odd jobs when the schooner was docked.

“It was all about living a life that was free from

responsibility,” Paley says, flashing a smile that’s still toothpaste-ad

material. “It was marvelous.”

His father didn’t agree—and Bill Paley knew it. So in 1975,

right after CBS: Reflections in a Bloodshot Eye painted him as a

ne’er-do-well, Paley decided to do something that might make his father

happy. He used his trust-fund money and, with a few partners, opened three

restaurants and bars in Washington and Baltimore: “I got in the restaurant

business because I loved food but also to please my father, who was a

great epicurean.”

In DC’s Adams Morgan, in the space now occupied by Perrys,

Paley had the Biltmore Ballroom. In Baltimore, he and his partners

established the Brass Elephant, an eatery that would outlast Paley’s

ownership by decades, closing only three years ago. And on Capitol Hill,

Paley created the Gandy Dancer, a spot that Washington Dossier, a

now-defunct society magazine, praised for its Fruit Fantasia and Hamburger

l’Elegante and for its unique mix of clientele—Hill staffers and theater

types. The magazine also asked, “Doesn’t it give you a warm feeling in

your tummy to know that Babe Paley’s son has a piece of the

action?”

Babe Paley’s son not only had a piece of the action; he was at

the center of it. “Bill always had a lot of attractive women around him in

the place, and he was a real gladhander,” recalls Keith Stroup, legal

counsel and founder of the National Organization for the Reform of

Marijuana Laws, who was a friend of Paley’s in the mid-1970s and a regular

at the bar. “If you were in Washington and politically active in the ’70s,

the Gandy Dancer was the place to be.”

The book High in America, which chronicles NORML’s

early years, says plenty of influence-peddling went on in the bar. “The

Gandy Dancer was the in spot for Washington’s younger political crowd,

much as Duke Ziebert’s restaurant had been for the older political

generation,” wrote author Patrick Anderson.

Duke’s was in business 44 years; the Gandy Dancer didn’t make

it to four. Paley and partners kept a tab open for NORML, which Stroup

says often went unpaid, and artists were given food and drinks in exchange

for art at the Biltmore Ballroom.

You could blame Paley’s drug use for the collapse of the

business, but he doesn’t: “I was in my twenties. I had no idea what I was

doing.”

• • •

Paley’s father, William, dropped by the Gandy Dancer just once.

After a night out with Henry Kissinger and with his limousine waiting out

front, the founder of CBS entered through a lower-level door, peered into

the dining room from the kitchen, ordered an egg-salad sandwich and onion

soup, and took the food away in a doggie bag. He later said he was

impressed with the place. But his son today doesn’t think his restaurants

truly pleased his father.

Then again, trying to please William Paley may have been

impossible. In her biography of him, In All His Glory, Sally

Bedell Smith paints the elder Paley as a “hard-driving” narcissist who

“treated his children much as he dealt with his top executives. . . . What

counted was that they knew he was in charge.”

Actually, his executives probably saw Paley more often. For

much of the year, William lived in Manhattan during the week and saw Bill

and his sister, Kate, in Manhasset only on weekends. But there were also

family trips to the Bahamas, Jamaica, and Europe. In Europe, Bill and his

father bonded over the pleasures of a gourmet meal. William Paley aspired

to live “the good life,” surrounding himself with beautiful things and

people. Smith titled an entire section of her book “The

Hedonist.”

On that subject, it’s like father, like son. Bill Paley markets

La Palina cigars as high-quality products that adhere to tradition and

enhance the good life. He tells stories of how his father lived that life

and how his mother embodied it. Lately, he’s been telling his own story,

too.

Paley is increasingly the public face of La Palina. He has even

started to appear in its ads. The bearded, white-haired Paley is now

selling himself as sort of a Dos Equis Guy for stogies. And what’s really

interesting about this cigar-smoking version of the Most Interesting Man

in the World is that he’s an ex-addict who is selling vice.

Proudly.

“When the time came to let go of everything else,” Paley says,

“I picked my favorite drug—tobacco—and decided to become an expert in

that.”

Last May, dressed in a navy suit with a crisp white

open-collared shirt and a cigar in hand, Bill Paley stood in a park in

midtown Manhattan and proclaimed that the park “is going to continue to be

a place that will be an oasis for people to exercise their

freedom.”

It was the second annual Legal Outdoor Smoke, an event that

jabs at New York City mayor Michael Bloomberg’s regulations against

smoking in public. Because the property where the event is held—Paley

Park, on the site once occupied by the legendary celebrity hangout the

Stork Club—is a private park funded by the William S. Paley Foundation,

Bloomberg can’t stop this smoke-in.

That’s about the extent of Bill Paley’s public politics,

though. He and his wife, Alison—whose late father, Albert Van Metre,

founded Van Metre Homes, a company that has built more than 15,000 homes

in Washington since the 1950s—don’t hold $1,000-a-plate fundraisers at

their 8,800-square-foot mansion in McLean. Paley typically eschews Capitol

Hill and Georgetown glitterati, preferring to befriend entrepreneurs,

artists, and gallery owners.

But he does take a very inside-the-Beltway approach when it

comes to cigars.

“One of the causes of the discord and vitriol that is happening

in politics nowadays stems from the very day they made it illegal to smoke

in the Capitol,” Paley says. “The term ‘smoke-filled room’ really does

have important historical meaning. That’s where things got worked out,

when, after sessions in Congress, politicians used to gather, smoke

cigars, and talk. I think there is something in the nature of tobacco that

makes this possible. The American Indians understood this. Whenever there

was something important they had to do, the first thing they did was smoke

some tobacco, because it opened up people’s minds and allowed them the

patience to listen.”

One thing Paley has no patience for, though, is comparisons

between cigars and cigarettes. He knows firsthand the damage cigarettes

can do: His mother, a smoker, died from lung cancer in 1978 at age

63.

“The tobacco is changed for cigarettes so that you have to

inhale it,” Paley says, fidgeting in his leather chair, his voice raised

for the first time in a 90-minute conversation. “It does not absorb in the

mouth like a cigar does. It goes to the lungs, and the lungs go directly

to the brain. It is the fastest delivery system you can have with a drug.

Faster than an injection. It impacts the brain so powerfully that the

neurochemicals change in response and it creates an

addiction.”

1. The Pasha

Named for: William S. Paley

Critics say: “Flavors of earth and roasted cashews with a hint of brown sugar.”

2. The Babe

Named for: Babe Paley

Critics say: “A medium-bodied cigar with full-on flavor and complexity.”

3. The Alison

Named for: Paley’s wife

Critics say: “Came out kicking . . . then offer[ed] a more floral bouquet.”

4. The Little Bill

Named for: Paley himself

Critics say: “Pairs well with cognac . . . Burn was smooth with a firm draw.”

He goes on for a while, discussing the addictive qualities of

all kinds of substances, including sugar and white flour. It’s an

impressive soliloquy, one that has been informed by years of

study.

When Bill Paley’s first son, Sam, was born in 1984, he decided

it was time to get sober. During his recovery, he poured himself into a

single subject: the nature of addiction. By 1990, he had made a full-time

career of it. Paley got licensed as an addiction counselor and began

working with wealthy addicts and their families.

He was describing his new calling to his father over lunch one

afternoon in the late 1980s. William Paley’s eyesight and mental faculties

were failing. His short-term memory was particularly bad. Bill told his

father he had gotten his counseling license and wanted to help people beat

addictions. His father said, ‘You know, you should meet my son Bill. You’d

be a really good influence on him.’ ”

Bill Paley clutches his heart as he recounts the story. You

might think he’s pained by the memory, upset that in his final days his

father would never know that the son who had caused him so much dismay had

gotten his life together. But he’s actually overjoyed. Paley believes he

had changed so much that his father saw him as a completely different, and

completely respectable, person.

“My father always thought that I was a hippie and a drug addict

and a failure and someone he couldn’t relate to,” Paley says. “But that

day, he was thinking something about me that was so

different.”

• • •

It was Cuba that did it. A trip to the embargoed island nation

and its cigar factories in the early 1990s fascinated Paley and hooked him

on cigars.

Even so, nearly 20 years passed before he decided to get into

the business. You can hardly blame him—cigars are a low-margin, high-risk

business. Three manufacturers control more than half of the US market. The

other half is split among dozens of companies, most of them tiny. That

adds up to consumer confusion. Walk into any cigar store and you’ll be

confronted with thousands of choices. And price won’t be your guide. A $6

cigar can be as good as or better than a $26 cigar. Blogs and magazines

can help, as can a good salesperson. But that means small cigar

manufacturers have to work hard to make their products stand

out.

All of which is why Bill Paley’s family story—and his family

fortune—was crucial to La Palina’s revival. “Bill had the money to

advertise and promote his cigars,” says Draper’s Matt Krimm. “A lot of

manufacturers can’t afford that when they first start out.”

A lot of manufacturers also might not get the initial acclaim

that La Palina received. The cigars have been widely praised by reviewers.

In fact, one of La Palina’s new releases—the Kill Bill, named not for the

movie but for the fact that the cigar, before it had had time to mellow,

was too strong for Bill Paley to finish in one sitting—was given a 93 out

of 100 by Cigar Aficionado. That makes it “outstanding” in the

magazine’s rating system and also placed it as one of the highest-rated

cigars last year.

For Paley, that positive reception is more important than

financial results—an attitude he says he gets from his father: “My father

saw very early that in the media business quality content is the most

important thing. He went out to secure the best entertainers and secure

the best content. That would get more people watching and listening, and

that would allow him to sell his advertising better. I follow that same

plan: I put content first, and success will follow.”

For now, though, not a lot of money has followed. Paley isn’t

certain of the numbers, but La Palina has sold a little more than 40,000

cigars in the past two years. That makes it a very small player. More than

13 billion cigars were purchased in the US in 2010, according to the

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Paley gets his tobacco from growers in Honduras, Ecuador,

Nicaragua, Brazil, the Dominican Republic, and Costa Rica, and he works

with several factories to assemble them, including in the Bahamas,

Honduras, and Miami. Some of his cigars command $22 or more. Others, like

the recently released La Palina Classic line, are priced in the sweet spot

for cigar purchases—between $6 and $8. All, Paley says, have sold well.

But do the back-of-the-envelope math and you get gross revenues of less

than $1 million over the past two years.

Meanwhile, Paley says he has spent about that amount on the

company to date: “I could have sailed around the world for the amount of

money I’ve spent on this business. But I wouldn’t have enjoyed it as

much.

“Not to be grandiose, but I feel like this is what I should be

doing. Every fiber of my being tells me that this is the best thing I

could be doing at this point in my life.”

• • •

Maybe, if he succeeds, Bill Paley can finally make his father

happy.

“My father was a very powerful man,” he says, “and I always had

a feeling that I had to live up to certain expectations. I’m sure that was

all just in my head—well, probably it was all in my head. But somehow with

La Palina I feel like I’m at least pleasing my grandfather. And in that

way, I hope I’m pleasing my father, too.”

He’ll never know for sure, of course. But Paley does know that

his foray into the cigar business has made his own sons happy. He started

just after both boys had moved away from home. Paley’s younger son,

Albert, 25, is now studying at the University of the District of Columbia.

His older son, Sam, 28, is a video-game developer who founded a Boston

company called Lantana Games.

“They have brains that are like mine—very attention deficit

disorder,” Paley says. “So I gave them a lot of space to learn a lot of

things and see what stuck.”

The boys gave him something, too. Years of free therapy.

Raising sons helped Paley work out many of the issues he had with his

father.

“I remember years ago my son Sam had done something that I

thought was stupid,” Paley says. “I don’t even remember what it was. I

started yelling at him. Then I stopped myself. I thought, ‘What am I doing

yelling? What am I trying to say?’ I realized I was trying to say, ‘I care

about you. I love you.’ And right then I realized that was what my father

was really trying to say for all those years, too: ‘I love you.’ ”

This article appears in the February 2013 issue of The Washingtonian.