Seth Hurwitz, the impresario behind DC’s legendary 9:30 Club, has quietly become one of the most powerful people in Washington’s music community, but he squirms away from talking about himself.

“I can’t tell this story again,” he says—how he went from booking kung fu movies at Adams Morgan’s long-gone Ontario Theatre to operating a live-music empire: Merriweather Post Pavilion, U Street’s restored Lincoln Theatre, and the 9:30; arena shows at the Verizon Center and Fairfax’s Patriot Center; and events like the Preakness Stakes’ InfieldFest.

On any given night, Hurwitz’s company, I.M.P.—the name is a nod to the 1963 Lesley Gore hit “It’s My Party,” fittingly—may have provided the entertainment for one of every three concertgoers in Washington. That portfolio will soon include the 6,000-seat venue anchoring the sprawling Wharf development in Southwest DC.

Hurwitz, 56, talks here about booking in the digital age, fighting off the Live Nation/Ticketmaster behemoth, and why this believer in live music wouldn’t be caught dead at a show in Austin, Texas.

Do you remember your first show?

My parents took me to see Peter, Paul, and Mary at Carter Barron Amphitheatre. My first real concert was at the Shady Grove Music Fair in 1972: Delaney & Bonnie, Roy Buchanan, Billy Preston. The opening act was Loggins and Messina.

Back then, there was no YouTube, Spotify, SoundCloud—everyone got music from one or two sources. Has it gotten more difficult to know what people will go to?

No. The charts out there are more scientific than they used to be. Billboard has this hot-performer chart. It makes it a lot easier. There used to be lots of nuance, and now it’s right there to read.

Thanks to those channels, I can watch any band I like, anytime I want, on YouTube. Why do people bother going to shows?

That’s not a concert—that’s a video. A live concert, if done right, is a fantastic social experience. You’re in a room, sharing it with people—the crowd noise, the applause. Most people are at a screen all day. We sell escapism. When you go into that room, everything else goes away.

Except screens. Does it bother you to see people taking pictures or tweeting the show?

I feel sorry for them that they haven’t learned to control their impulses. I think it bothers other people, for the same reason they don’t allow texting at movies now. It’s not right.

Millennials seem to be drawn to music as social events, festivals, and electronic music. Is mainstream rock still part of the culture?

The problem with rock is that there’s just not a lot of people making it. But the people who do . . . . Jack White the other night took everyone on a journey. He took chances, took the show in different directions. It felt like the days of real rock concerts when I was a kid.

What do you mean, “real rock concerts”?

You used to show up and you didn’t know what was going to happen—with the show, the music. It wasn’t this planned set list. It wasn’t Katy Perry. Katy Perry’s a fantastic product, but it’s a different show. Dave Grohl calling audibles—that’s a rock concert. It’s supposed to be this thing that takes a direction and has ups and downs, hopefully a crescendo. When I went to concerts as a kid, everyone was on the same roller-coaster ride.

At the old 9:30 Club, you had video monitors by the bar. What happened to that footage?

I’d like to know myself. I didn’t tell anyone to record them, because that’s illegal. I come to find out later they were actually recording. Apparently there was this vast collection of tape. So when we moved the club, this treasure trove of tapes I wasn’t supposed to know about was moved to someone’s house, which burned down. We don’t know if the tapes burned down with it. We have no idea where they are.

If someone has them and reads this article and would like to make a lot of money, we’ll buy them. We can make arrangements to leave them somewhere and pick up an envelope of cash, no questions asked.

It’s been a long time since DC produced a nationally recognized band. Why are we producing fewer big acts?

I don’t know if we ever had bands that had big followings.

There are certainly bands associated with the old 9:30 Club—Fugazi, Rites of Spring, Nation of Ulysses.

I knew you were going to say Fugazi, but that’s really the only band that got big. Of course, they fought getting big. And then a lot of bands, because they were from DC, or that scene around Dischord [Records, a local independent label], got a lot of attention.

How do you keep tabs on the local scene? When’s the last time you went to the Black Cat?

I went to a Christmas party there about five years ago. I don’t go out to a lot of shows anymore—I get up early and I work all day. I go when they get to the level where I need to. I’ve been out the last few nights checking stuff out—Sam Smith at Echostage; I saw Paolo Nutini at the Lincoln; last night I saw Stromae.

But those are all your shows.

I hate going to other people’s shows where they tell you where you can stand. When I see a band, unless I’m there as a fan, which is not very often, I’m pretty much done in five minutes. When I see Die Antwoord at Echostage, it’s to see what their thing is exactly. I’m not there to watch Die Antwoord for an hour. I have a house in Austin, and I go because I love the town and the food. People say, “Oh, do you go to a lot of shows down there?” No. For me it’s like a gynecologist going to a strip club.

What’s the last show you saw purely for enjoyment?

Willie Nelson at the 9:30 [in September].

You were a vocal opponent of the Live Nation/Ticketmaster merger. [The country’s biggest concert promoter combined with one of the largest ticket brokers in 2010, forcing promoters like Hurwitz to sell tickets through a major competitor.] Four years later, I.M.P. seems to be doing pretty well.

We’ve always done pretty well. But Live Nation already had an unfair competitive advantage and it only got worse. Anyone could see there was something wrong with the promoter and the ticket company, these two supposed monopolies, linking up. To have my competitor selling my tickets, having all my information—it made zero sense.

The bigger problem is competing against a promoter that has zero intent of making profit, who only cares about cash flow. How do I compete against that?

How do you?

I create venues that are compelling for the bands. It’s going to make them look goofy if they play the night after midget wrestling. We don’t do that.

Does it ever work in reverse?Are there acts you won’t book because they’d hurt the I.M.P. brand?

I guess I’ll never book this act again, not that I ever booked her anyway: Agent calls, wants to play Demi Lovato at the 9:30 Club. I’m not playing Demi Lovato at the 9:30 Club. “Why not? It’ll sell out.” I said, “It’s not cool.” “But she wants to play the cool places.” I’m like, yes, but the very reason you’re calling me is that I don’t play Demi Lovato. Go play the other place. [Lovato wound up playing the Patriot Center on March 2, booked by Live Nation.]

Who were you wrong about?

The Beastie Boys. Then they had that big hit, “(You Gotta) Fight for Your Right (to Party).” They played 9:30 and I said, “These guys will never get any bigger—they’re horrible.” Someone I work with saw the White Stripes and said, “These guys suck. I don’t think they can sell out 9:30 again.” It’s not about my taste anyway. You never know.

Are there any bands you won’t book again?

I had some act named Murder City Devils, and the staff asked me to never book them again because they were really nasty and rude. There have been some rap acts—that whole scene with showing you got a gun. I don’t care how much money they’d make me. If my staff is afraid, they’re not playing.

Do you still manage the bookings yourself?

I used to do it all. Now Melanie Cantwell, who was my assistant for ten years, does the 9:30 Club and Echostage and the Lincoln. She does a better job than I did and in the face of more competition. I book Merriweather and all the bigger shows. But I’d eventually like to not do those either, because the people in my business, they’re just animals.

These are agents?

Do you watch Entourage? You know Ari? That’s what I deal with all day, and that’s the better ones. I’m competing against this company [Live Nation/Ticketmaster] that has employees, not entrepreneurs like me. When agents push us too far, entrepreneurs can say “Go f— yourself.” But employees of a monopoly agree to deals that make no sense, just to control the artist, and keep them away from us.

But you can say that.

I say it a lot. And when I do, they’re shocked.

You moved 9:30 to V Street when the U Street area was starting to grow. Do you fear that people who paid $800,000 for their condo will object to a concert next door?

Their ads promote the fact that you’re right next to the 9:30 Club, that this is an attraction. So we’re saving all those ads.

What would the Seth Hurwitz who booked the Ontario be most surprised at about the Seth Hurwitz of today?

The sheer magnitude of how big things got. This was never intended as “and some day, we’ll do arenas.” I’m surprised today. I used to go to Merriweather as a kid, and now it’s my venue. When I booked the Ontario with old kung fu movies and blaxploitation, the Lincoln was my competition.

Here we are on a Wednesday night in downtown DC, and there’s 1,200 people having a great time, and I had something to do with that. I’m just standing there—I don’t really want anyone to recognize me. But it’s like, I’m the reason there’s all these people at this spot right here. To have the feeling you’ve had this influence on a city, on people, their memories, their lives—I love that.

Seth Hurwitz’s Greatest Hits

March 12, 1972:

A 13-year-old Hurwitz attends a four-act concert, opened by Loggins and Messina, at Gaithersburg’s Shady Grove Music Fair.

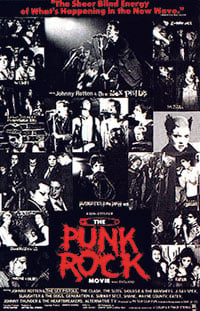

May 29, 1980: Hurwitz and partner Rich Heinecke book their first concert, the Slickee Boys at Adams Morgan’s Ontario Theatre, for the local premiere of The Punk Rock Movie.

January 3, 1981: New York garage-rockers the Fleshtones play I.M.P.’s first show at the original 9:30 Club at 930 F Street, Northwest.

December 1986: Hurwitz and Heinecke buy the 9:30 Club from original owner Dody DiSanto.

June 15, 1988: Fugazi’s 9:30 Club debut puts DC on the post-hardcore-punk map.

January 5, 1996: The new 9:30 Club opens in the old WUST Radio Music Hall at 815 V Street, Northwest, with the Smashing Pumpkins.

June 13, 1998: After lightning delays the Tibetan Freedom Concert at RFK Stadium, Radiohead gives a surprise performance at 9:30. Jennifer Aniston and Brad Pitt are spotted in the balcony.

August 14, 2001: An altercation between 9:30 Club employees and a guest of the Seattle punk band Murder City Devils ends the group’s set. The Devils are banned from the club for life.

October 14, 2003:

I.M.P. is announced as the new promoter for Merriweather Post Pavilion.

September 23,2006: I.M.P. books the first Virgin Festival at Baltimore’s Pimlico racecourse. (The festival moved to Merriweather in 2009 and was canceled for 2014.)

February 24, 2009: Hurwitz testifies before Congress against the merger of national concert promoter Live Nation and Ticketmaster.

June 27, 2010: Courtney Love melts down and strips down in a train-wreck 9:30 show.

June 27, 2013: DC gives I.M.P. the keys to U Street’s historic Lincoln Theatre.

March 19, 2014: Ground is broken on Southwest DC’s massive Wharf development, including a 6,000-seat theater to be operated by Hurwitz. The opening is slated for 2017.

This article appears in the November 2014 issue of Washingtonian.