Sandy Lerner sits in a field in her black Range Rover, the door

emblazoned with the crest of Ayrshire, her 800-acre farm in Upperville,

Virginia. Out of the tall grass teeters a days-old calf with a white face

and black ears, one of more than 200 born to her 1,200-strong herd last

spring. Against the backdrop of the Blue Ridge Mountains, the calf

stretches its gangly legs and takes a few experimental hops.

“Look!” says Lerner, who usually seems aloof. She watches with

delight, as if it were her own child walking for the first time. “I love

watching them–it’s like cow TV. Even if you know they won’t be here for

long.”

Which means here today, hamburger tomorrow. Or maybe not.

Lerner–who made millions founding (and then leaving) Cisco Systems, an

early technology start-up, and Urban Decay, a cosmetics company–hasn’t, in

the 15 years she’s been raising beef by USDA organic standards, made money

doing it. Now she’s torn: keep raising these gorgeous animals to supply

her nearby Hunter’s Head Tavern and Home Farm Store, use them for her

high-end Furry Foodie pet food, or sell the lot and get out

altogether?

“I put my beef up to any. Am I going to keep subsidizing it

forever? Absolutely not,” says Lerner, 56, her eyes steely behind round

glasses and her hair–which, when hanging down, reaches the small of her

back like Morticia Addams’s–gathered into a messy bun. The woman the press

has variously tagged “wispy” and a head-turner now favors jeans, sky-high

wedge sneakers, and baggy T-shirts paired with necklaces she beads

herself.

“In the next few months, all that beautiful heritage-breed

food–your dog might be eating it,” she says. “Is that what the American

consumer wants? I would be happy to end up the nation’s primary supplier

of the best pet food on the planet.”

Lerner’s life has always centered on animals. The farm has more

than 70 cats, which she deems as essential to Ayrshire’s ecosystem as its

turkeys, chickens, pigs, cattle, horses, and dogs. She treats all

creatures well–her operation is certified organic by Oregon Tilth, a USDA

certifying body, and certified humane by the Humane Farm Animal Care

program, adhering to a strict code dictating how animals are treated not

only in life but in the way they’re put to death.

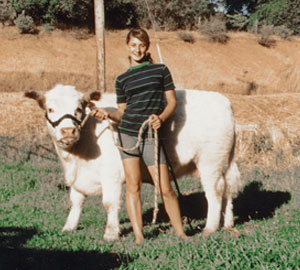

“I basically grew up alone in a barn,” says Lerner. “I was the

only child on the farm, and my aunt and uncle had full-time jobs like most

farmers did.” She was just four years old when her parents divorced, and

she eventually went to live with her aunt and uncle on a cattle ranch in

the foothills of Clipper Gap outside Sacramento. She spent many summers

with another aunt in Beverly Hills.

She credits her aunt and uncle–and nine years in 4-H–for who

she is today. Uncle Earl Bailey, and Aunt Doris, who is now 93, ran a

home-heating-oil business–leaving Lerner, a self-described shy, awkward

child, to care for the cattle. At age nine, she started raising her own

steer.

“There was no division of boy and girl work,” Lerner says. “My

aunt was one of the most tenacious women on the planet–she was strong and

vocal, and she just would not give up.”

Born on Bastille Day 1955, Lerner, a child of the ’60s, has

always been a rebel. Her past is punctuated with controversy, perhaps the

most defining one her unplanned exit from Cisco Systems–the company’s

equipment today runs an estimated 80 percent of the Internet–which she and

then-husband Len Bosack formed in 1984, leaving six years later with $170

million between them.

In 1996, after seeing 50 properties, she paid $7 million for

Ayrshire, in a wealthy area where neighbors have last names like Mars,

Fleischmann, and Mellon. Her arrival seemed to be good news in a community

that cares about land preservation–the owners long waited for a buyer who

wouldn’t subdivide the farm. But on arrival she closed the land to the

Piedmont Fox Hounds, members of which had been running in the area since

1840. She then bought a historic home central to the nearby village of

Upperville, intending to establish a pub. When some opposed her, she

erected a chainlink fence around it and posted a demolition

sign.

“She’s not thin-skinned,” says Harry Atherton, then chair of

the Fauquier County Planning Commission. “Most people live here because

they want to, and they don’t like change. Anyone else would have walked

away.”

The battle got ugly, with Lerner receiving what she calls

“death threats” from a neighbor. But deep pockets can fund lawyers, and

Lerner had them. (Many locals still decline to discuss her on the

record.)

The battle raged for a year and a half before the zoning board

found in her favor on the pub. Now many of her former opponents’ names can

be seen engraved on the pewter mugs that hang above the bar for regulars.

Perhaps coincidentally, when she finally got her way she named her

English-style pub the Hunter’s Head. Over one fireplace hangs the visage

of a terrified-looking man wearing a riding helmet.

That kind of cheek is trademark Lerner. Forbes

magazine sent a photographer to Ayrshire, and she posed naked on a Shire

horse. In her Urban Decay days, she wore blue body paint to a party for

the British prime minister. She had a “trailer trash” party to launch the

luxury motor home in which she took her cat to Williamsburg and Niagara

Falls in the last weeks of its life. At the party, there were lots of

leotards, exposed hairy stomachs, and moonshine.

If she seems to step over the line, maybe she’s unsure where

the line is.

“Body language means nothing to me, but I can tell you what a

cow is thinking from 50 paces,” she says. Though Ayrshire has a large main

house, which she spent $2 million to restore, she lives in a cabin on the

farm. “I live alone with my cats. I’m your typical nerd who lacks social

skills.”

She says that because her only model for childhood is her own,

she’s never had kids. She doesn’t talk about her marriage or relationships

except to say she was married and does date. Would she remarry? “Never say

never,” she says. “Never is a long time.”

When she does care, it’s on a generous scale. She’s spent

thousands of dollars on pioneering medicine for her cats, dogs, and

horses. She built a new sound system for a local church and regularly

opens her farm to charity events, many of which benefit animals. She has a

collection of carriages and a team of Shire horses, which she lends out

for local Christmas parades and for friends heading to the chapel to get

married.

Driving through Ayrshire Farm, Lerner scribbles notes on a pad

stashed between a diet Snapple and a York Peppermint Patty. As she tours

the meat locker, she takes one look at the hanging carcasses and turns on

her heel. “Excuse me,” she says, her voice flat, “I’ve got to go pitch a

fit.” It turns out the animals were hanging with their kidneys intact;

kidneys, she has repeatedly told her staff, need to be taken

fresh.

“Last year we had profitable turkeys, the chickens are driving

over to the right side of zero, and I think I will get my pigs over, if

not very close. The only thing I have not been able to drive in the right

direction is the beef operation,” she says, tapping a nail painted with

black polish.

Lerner started at Ayrshire as she had as a kid, with heritage

cattle, but “it didn’t take a genius to figure out you need an integrated

farm to produce the waste you put back on the field.”

So she added chickens, turkeys, and pigs, even a garden–now

defunct, as it couldn’t turn a profit–making the farm a sustainable system

in which the animals and their waste power the soil, which in turn

nourishes the animals without chemical pesticides, medicines, or feed. In

separate operations, she buys lamb and raises veal, all of which she

serves and sells at the Hunter’s Head Tavern and the Home Farm Store. She

also supplies high-end restaurants such as Restaurant Nora and the Inn at

Little Washington, and organic markets such as MOM’s in Maryland, but

rising fuel costs cut that profit to the bone.

Lerner praises the British (she has a home near Bath), who

established an organic economy after mad-cow disease decimated their food

chain in the ’90s.

“The Brits have saved their countryside, put back rural

industry, and rebuilt the food chain,” says Lerner of programs that assist

not only farmers but entrepreneurs setting up supporting businesses such

as canning and processing. According to the US Department of Agriculture,

about 80 percent of food costs accrue after the product leaves the farm–in

transporting, processing, and distributing. Farmers get 20 percent.

“There’s no food infrastructure here,” she says. “Farmers have to be

carpenters, engineers, marketers–that’s why so many give up.”

Lerner’s beef is with some of the USDA regulations governing

the term “organic.” For most livestock, to be labeled as such, the

animal–or its mother before it’s born–must be fed organically and provided

pasture with no drugs or hormones during the last third of its gestation.

Meat from Lerner’s Home Farm Store has an ID number on the receipt,

tracing it back through processing–she bought her own processing facility

in Front Royal in 2008–to the animal itself. And all these operations must

be documented for USDA certifiers, who check in regularly. If the animal

gets sick, it must be treated, and if that requires a non-approved

substance–Terramycin, for example, which treats pink eye, a common cow

condition–the animal is no longer considered organic.

In other words, the investment is lost.

“Your capital is tied up too long before you see a return,”

says Lerner. Even with consumers willing to pay a premium for organic

beef, the costs are often not offset by profit. “What is the risk over

four years of something happening to that animal that will remove its

organic certification? It is a barrier to entry that I believe was

constructed by the packer-cartel beef lobby.”

Lerner fumes when she talks about this “cartel,” the four

meatpacking companies that dominate the market–Cargill, National Beef,

JBS, and Tyson.

Ayrshire is in a tough market space. A medium-size farm but not

a family farm, it has all the expenses of professional staff–vacations,

insurance–without the economies of scale of large producers. Or the

subsidies: Of $261.9 billion in farm subsidies paid in the US between 1995

and 2010, most has gone to the largest farmers, according to the

Environmental Working Group. Some 62 percent of American farmers get no

subsidies.

“To be certified organic more than doubles the cost of raising

the cattle,” says Mike Brannon of Old Line Custom Meat Company, a

medium-size beef producer in Maryland that raises beef mostly on pasture

without hormones. Even with the premium that organic beef commands at the

cash register, he says, “I just don’t see the numbers

working.”

Which is why many farmers are instead using labels such as

“local,” “natural,” and “pasture-raised” to market their

products.

“Buying local has been a byproduct of trying to find the

best-tasting ingredients to put into cooks’ hands,” says Ryan Ford, owner

of the Organic Butcher in Charlottesville. Despite the name, many of his

suppliers are not certified organic. “All our products are natural,

non-genetically modified,” he says. “Our customers want a local product

that is sustainably raised, but they don’t really require us to carry

organic.”

“I like to use the term ‘beyond organic,’ ” says Derek

Luhowiak, who worked at Ayrshire and now with his wife, Amanda, owns the

Whole Ox butcher shop in the IGA supermarket in Marshall, Virginia. “A lot

of people can’t afford the certification, but what they do have is

transparency. They’re using organic feed, the chickens are running

around–but it’s a huge trust issue. We have to trust the farmers, and you

have to trust me.”

Which is fine if you know the farmer or the butcher, but

marketing terms such as “pasture-raised” and “local” aren’t backed by any

regulations. Beef may be “pasture-raised” on grass treated with

pesticides. Or be “local” and fed conventional grain, which almost

certainly has some genetically modified ingredients.

“The organic label is the gold standard,” says Gwendolyn Wyard,

associate director of organic standards and industry outreach for the

Organic Trade Association, who works with farmers and the USDA in trying

to ensure that organic standards are rigorous and transparent but

achievable. “You can’t just slap the word ‘organic’ on something, not

anymore.”

Lerner is passionate about the benefits of organic beef, both

to human health and the environment: She was a vegetarian for 30 years,

until she raised her own organic, humanely raised and processed animals.

But this is one passion she may not be able to sustain.

“If I dispense with organic, my cost of feed would go down

four-fifths,” says Lerner. But organic is the only feed she can be sure is

without genetically modified ingredients and grown without pesticides,

both of which she believes lead to harmful side effects.

“Cargill and Tyson are not worried about the family farm,” says

Lerner. “They’re worried about mine, and Niman [Ranch], medium-size farms

that could take regional markets because people are trying to buy local.

They are very smart, very well funded, and they hold the processing

facilities hostage. And I think they’ve won.”

Now in addition to spending time trying to meet the organic

market, Lerner is spending time separating her operations in a way that

would make them easy to divest.

“As the organic market matures, mid-sized organic farms are

being acquired by the food conglomerates to give them instant healthy

cred,” Lerner writes in an e-mail. One day she’s hot for the challenge,

the next tired of it.

She has separated the parcel on which her cabin stands from the

farm, should she decide to sell the farm. Her cats and her dog are the

only things she’s adamant she’ll keep.

Sandy Lerner has always been riled by the powers that be. She

remembers lying on the floor at age 11, waiting to be incinerated by a

nuclear bomb. She graduated from high school at 15 and studied political

science at California State University, Chico, and then at Claremont

Graduate School, where she first used a computer.

“My first thesis was on American antitrust legislation–back

then there was nothing off the shelf; you had to program it from the word

go,” she says over lunch at her pub, where she orders a meatball sub and a

Coke Zero and asks what’s for dessert–she says she has a sweet tooth. She

eats here often and engages in small talk with patrons, who ask her about

her trees or a planned racquetball court.

In 1976, Lerner shifted focus to computing and applied to

Stanford, where she not only was accepted but was paid $25 an hour to

program–a fortune to her at the time: “And I could work whenever I wanted,

in jeans and no shoes.”

In those days, the collective brainpower at Stanford probably

made it glow from outer space. Collaboration with Xerox’s Palo Alto

Research Center, home of the first Ethernet, attracted Department of

Defense funding of technologies now collectively known as the Internet.

Lerner, along with Len Bosack, a whip-smart computer scientist she

eventually married, worked on a multiple-protocol router, key to

inter-network connectivity. When Stanford dithered over making the

technology available to research partners at other universities and

corporations, they left, founding Cisco (short for San Francisco) Systems

in December 1984.

“Len and I thought that was against the spirit of collaborative

research and the use of public funds for the Internet and fundamentally

unreasonable,” says Lerner. She seems too shy to make eye contact when

talking, looking instead at your neck and checking in every so often just

to see if you’re following her.

By 1987 she and Bosack were selling $250,000 worth of routers

each month. The company grew to $27 million by 1989 with funding from

Sequoia Capital’s Don Valentine, who appointed a new CEO. In 1990, the

company went public and Lerner was ousted; Bosack followed.

“I thought they were partners–we had no employment contract,

our stock was only half vested–and we used their lawyer. Can you spell

dumb?” says Lerner. “It was time for us to go–the company was mired in

bureaucracy–but the way it was done was unprofessional and unfair,

inhumane. Cisco broke up my marriage, ruined my health.”

She’s still bitter, but she’s not letting that spoil her lunch.

She declares the meatball sub, which she worked hard developing, a

triumph.

“Forgiveness was not in her vocabulary,” Valentine told a group

of students at Stanford Graduate School of Business in the fall of 2010.

“When somebody . . . didn’t do it the way she wanted it, she shredded them

publicly.”

Lerner admits she has trouble accepting other people’s answers.

“If a man is blunt and strong and holds his ground, he’s manly,” she says.

“I don’t think Patton or Steve Jobs or anybody else who made themselves

and their fortune–Edison was apparently a big SOB–does anyone say they

weren’t nice?

“I think a large part of it is I don’t have a great

personality. I am fairly blunt and very shy–but who cares? Everything I’ve

done, it needed to be done.”

At 35, she had money to do it. Though they now live on

different coasts, she and Bosack established a foundation with most of

their proceeds: He likes weird science–the search for

extraterrestrial-intelligence (SETI) –and she animals; the Luke and Lily

Lerner Spay/Neuter Clinic at Tufts is named after two of her

cats.

“Len and I have been very involved and careful,” says Lerner of

the foundation, recalling a story about a man who wrapped his Ferrari

around a telephone pole and died the day his company went public. “Money

has been a very enabling thing. On the other hand, I pay absolutely no

attention to it. I’m not talented or beautiful–I don’t think a lot of

people pay attention to me other than I have this money.

“It’s not that it defines me, but it enables me to do the

things that I do–be an organic farmer, publish my book.”

Lerner’s book, Second Impressions, is a sequel to Jane

Austen’s Pride and Prejudice, which was initially titled

First Impressions. Lerner fell for Austen in 1982, when she saw

the BBC series Pride and Prejudice, starring Elizabeth Garvie

(now a friend) as Lizzie. For Lerner–who had already caught Anglophilia

while captivated, along with the rest of the world, by the romance of

Princess Diana–it went right into a vein. The civility, the confidence,

the humor, the pristine countryside all stood in glorious contrast to the

nerdy computer world in California, where the orchards she grew up in were

being bulldozed for strip malls. Lerner has read every word of Austen an

“unjustifiable” number of times and was at an Austen convention in 1992

when she found that Chawton House–once owned by Austen’s brother and on

the grounds of which the novelist wrote six books–was in

receivership.

Lerner called her secretary and eventually purchased a 125-year

lease from the Knight family–1.1 million pounds for the house and another

250,000 for the stables.

“It was a hell of a deal: 300 acres, an Elizabethan house, and

400 years of dereliction,” says Lerner, who bought it sight unseen. “I

either wanted it or I didn’t. I never test-drive cars,

either.”

The town was in a tizzy: Would this American firecracker build

an Austen theme park in their beloved Hampshire countryside? Her vision: a

study center to house her collection of books by and about English women

from 1600 to 1830–now more than 10,000 works, with the most rare digitized

for online reading. Lerner began collecting them in 1996, believing that

early women writers didn’t get enough credit for their role in the genesis

of the novel.

But the townspeople didn’t want the traffic, the parking, or

her fancy landscaping restoration. It was a standoff. Full approval for

the $10-million project took seven years.

She didn’t sit on her hands and wait. While Chawton simmered,

she turned her attention to makeup, founding Urban Decay in 1995, a

cosmetics company typified by edgy lip and nail colors including

“asphyxia,” “roach,” and “bruise.”

“As we all do, my youthful face was getting less youthful,”

says Lerner, whose aunt recommended she use makeup. “I adored her, so

okay, but all the makeup wanted me to look like Christie Brinkley. I

thought if I have to fight with my face the next 60 years, this better be

fun.”

The line, with typical Lerner irreverence, also featured body

paint and temporary tattoos. (She had one of those designs, a leafy

question mark, permanently inked on her arm for her 47th birthday.) The

company has a strict no-animals testing policy. Dark colors became

industry standard, and Urban Decay sold to LVMH in 2000 for a reported $20

million. (Former friend and horse trainer Pat Holmes took Lerner to court,

claiming a founding role, eventually winning $1.4 million.)

When Chawton was finally approved, she closed off the estate to

hunting, keeping draft horses and chickens and establishing an organic

garden; the produce is sold locally and used for private parties at the

estate. Now the house, the grounds, and the library are open to the

public.

“It’s trench mentality–just keep your head down and keep

going,” says Lerner of her efforts. “The pub was the same, the farm was

the same.” But she pleads tired of the climb.

“My goal is to do nothing,” she says, paraphrasing a line about

her hero, former British prime minister Benjamin Disraeli: “To become what

he is from what he was is perhaps his greatest achievement.”

Yet in the next breath she’s talking about her projects–she

hasn’t watched television regularly since The Addams Family was

canceled in 1966, except for the occasional Masterpiece Theatre and, of

course, Princess Diana’s wedding, choosing instead to read. She’s

integrating the operations of the farm, pub, and store to be run on iPads.

She’s designing the children’s menus, complete with word puzzles and

coloring, as well as bumper stickers. And there’s Sono Luminus, a record

label she and Bosack founded in 1995 that’s headquartered in nearby

Berryville; its recording of Eliesha Nelson playing viola works by Quincy

Porter tied for Best Engineered Classical Album at the 2010 Grammy

Awards.

Much of the past year was spent writing her book, which she has

been thinking about since 1984. Published as the first title from Chawton

House Press, Second Impressions–under Lerner’s nom de plume, Ava

Farmer–came out last November. She says she knew so much about Jane

Austen’s world by the time she wrote the book that she literally channeled

her. (Though she’s nuts about the English novelist’s work, she isn’t so

sure they’d be friends, as Lerner is Jewish and Austen was a product of

her time.) Now she’s considering writing a sequel set in

Virginia.

Some days, she can see herself living in England in the

future.

“They have a very enlightened view of animals,” she says.

“Here, there’s this constant stress that goes on for anyone into

conservation. They haven’t wrecked their countryside in 10,000 years–we

wrecked ours in 200. One small turn of politics and this could be a strip

mall.”

This article appears in the May 2012 issue of The Washingtonian.