Stanley Plumly’s father and grandfather made a fortune in the Ohio and Virginia lumber business. Then came a falling-out. The father, Herman—a sentimental man with a weakness for strong whiskey—left the family firm to work for the competition and was cut out of his father’s will.

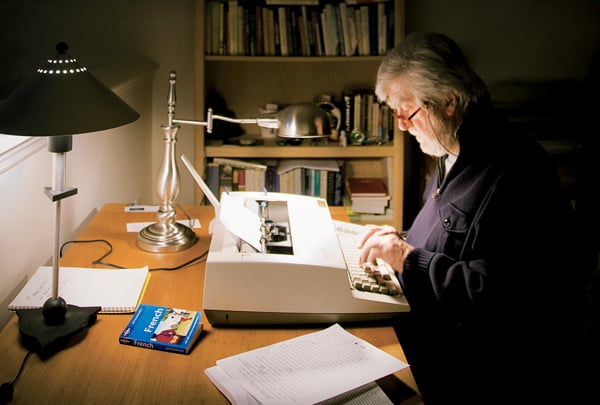

It was into this familial turmoil that Plumly was born in 1939. He got a Royal typewriter in high school—when a teacher suggested it as an antidote for his chicken-scratch penmanship. “I loved the sound of the keys,” Plumly says. “It was a kind of music you were playing.”

Since then, in nine elegaic collections of poetry often exploring man’s mortality and the ecstasy of the natural world, Plumly—a professor at the University of Maryland for the past 24 years—has been making sense of his life story.

In “Sweat,” a poem from 2007’s Old Heart, Plumly imagines his father’s beaded brow the summer he built their house:

. . . crude oil and water mixed, as if, by / nature, he were fuel, combustible, on fire, the welder whose / work it was to burn, the builder who dismantles, brick by board, / his own ruined body in order to rebuild.

Plumly’s latest book is Posthumous Keats, a personal biography of the Romantic poet who died at 25 of tuberculosis. Keats was convinced he’d failed as a poet, only to achieve literary immortality in his posthumous life.

How literary scholars will remember Plumly is uncertain. “It’s the fear of every poet that your work will die young,” he says.

A line from Old Heart might be as good a tribute as any: I died, I climbed a tree, I sang.

This article first appeared in the April 2009 issue of The Washingtonian. For more articles from that issue, click here.