Not much remains of the place where William Raspberry spent his high-school years in the late 1940s and early 1950s. The rural Mississippi campus is now mostly scrub brush and weeds. Nearly all of the buildings are gone, and the few that remain are crumbling.

Raspberry, carefully steering his rental car over the rutted road, points out a round gazebolike structure, its domed roof listing. “My father built that,” he says.

Both his parents taught at the school–his mother English, his father carpentry and masonry. The house on the back part of the campus where Raspberry was born and lived with his parents, brother, and three sisters no longer exists. His mother, Willie Mae Raspberry, will be 98 in February–she lives near the old school Raspberry remembers so well.

This trip to Okolona, a rural town of 3,500 people in Chickasaw County about 20 miles south of Tupelo, is more than a nostalgic visit for Raspberry, who has lived in Washington more than four decades and spent most of that time writing a column for the Washington Post. He has come home for a purpose: to launch a program aimed at encouraging kids to succeed in school. He’s not a celebrity figurehead. He’s funding the program himself. He admits it has something to do with immortality.

It’s been 50 years since Raspberry left Okolona. And now, at 68, after a career in which he has accumulated a Pulitzer Prize, honorary degrees, and professional respect and admiration, Raspberry is looking homeward. This depressed little town has never been far from his mind, and he has “warm and fuzzy” feelings for the Episcopal Church-run school–called Okolona College–that prepared him for the larger world he lives in. Raspberry feels he owes something to Okolona and all the people who helped him get started.

Talking to his contemporaries in Okolona today, Raspberry says he can pretty much tell after five minutes of conversation which ones were touched by Okolona College and which were not. The school, which opened in 1902, went from grade nine through the first two years of college. It had an enrollment of about 200, and many of the kids lived on campus. The school was closed in the late 1960s when its leaders decided that if they opposed segregation in the white schools, they shouldn’t be running a black school.

Raspberry attributes much of his success to Okolona College and to the interest and guidance he received from his parents and other adults. That, he believes, is the crucial element in education so often lacking among disadvantaged children today. Raspberry thinks the best way to help Okolona’s children is to focus early on the attitudes of parents.

Most parents love their children, Raspberry says, but many don’t know how to manifest it beyond “dressing them cute and buying them fancy sneakers.” If asked, he says, these parents will say they think education is important, but they don’t communicate that to their children.

His parents’ generation, Raspberry explains, valued the concept of education because it had been denied them. And they instilled that sense of value in their children.

“Today’s uneducated parents,” he says, “tend to be people who were not denied education but for whom school simply didn’t work. They were the people who didn’t do well in school and dropped out as soon as they could legally do so.”

The earlier generation, Raspberry says, would “sing songs about how education will save you.” The present generation doesn’t have similar songs to sing. They think that school works for some people but probably not for them. “I think it could work for them and theirs, but they have to be convinced of that,” he says.

So Raspberry has come home to try to convince them. He thinks that if parents will talk to their children and emphasize the importance of education, that will be a major step toward success. His pilot program will bring in advisers to set up a cadre of parents who will train other parents on how to stimulate their children the way many middle-class parents already do.

He has warned his three adult children–all have master’s degrees–that he’s going to spend some of their inheritance on his Okolona project.

“They have the grace not to be terribly surprised by this. I was a little bit surprised myself at the intensity of the feeling that I brought into it. I just take it as a compliment that they feel ‘Dad’s got a decent streak in him, and we don’t know how it’s going to come out.’ “

Rasperry says his idea germinated during reunions of his fellow Okolona students. “We were celebrating what a difference the school made in the lives of so many of us before it closed. It finally occurred to me that here were some intelligent people who caught a break or two, and that experience should amount to more than good nostalgic feelings.”

When Raspberry was growing up in Okolona, schools for blacks were separate from but hardly equal to those for whites. The black public school went only through tenth grade. Okolona College was the only place area black students could get the two additional years needed for a high-school diploma.

A private school affiliated with the Episcopal Church, Okolona College “gave us some protection and gave the faculty and staff the wherewithal to save us from as much of the downside of segregation as was possible,” Raspberry says.

The town’s theater was segregated. “We had to sit in this cramped little balcony if we went downtown,” he recalls. So the school showed movies in the auditorium. The school’s president managed to bring actors, singers, and other performers to the school when they were traveling through the area. “We got a chance to hear snatches of opera and little bits and pieces of things that made us feel that we were culturally aware. We got exposed to more things than rural kids in Mississippi ordinarily would have been exposed to.

“We were utterly segregated, but our lives were managed in such a way that we didn’t have to come into contact with white people that much. So it was kind of a sheltered existence in an interesting way. At any rate, it finally dawned on me, and I may not have this right yet, but it seems to me that at least a good part of what was happening at that little school didn’t have to do with brilliant teachers or great facilities or any of those things but with kind of a network of caring designed to protect us and bring us along and let us be what we could be.”

Over the 36 years that Raspberry has been a Washington Post columnist, a good many of the thousands of columns he’s written have been about education. Always in the back of his mind has been the question of what it takes to inspire children to succeed in school.

Raspberry graduated from Okolona College in 1952, two years before the Supreme Court decision mandating desegregation of public schools and several years before Martin Luther King Jr.’s transforming civil-rights movement got under way.

He left Okolona after graduating from high school and went to live with his sister in Indianapolis. He graduated in 1958 from Indiana Central College. He joined the Army and during his tour of duty was stationed in Washington as an information specialist. He joined the Washington Post in 1962 as a teletypist. Four years later he began writing his Potomac Watch column in the Metro section. His independent, provocative opinions attracted attention. Time magazine described him in the late 1960s as “the most respected black voice on any white U.S. paper.”

Soon Raspberry was one of the most respected voices of any color. He never saw his role as being a black voice. He focuses on finding solutions.

During the late 1960s, when the black-power movement was calling for confrontation rather than nonviolent action, Raspberry was one of the few black writers to challenge the angry leaders.

“I don’t underestimate either the persistence of racism or its effects,” he wrote in his column, “but it does seem to me that you spend too much time thinking about racism. . . . It is as though your whole aim is to get white people to acknowledge their racism and accept their guilt. Well, suppose they did. What would that change?”

When asked if he’s angry about his experiences growing up in the segregated South, Raspberry answers: “I suppose I’ve got the basis for being angry if I thought anger was a useful emotion. I don’t happen to think it is. And the people I’d be angry with are mostly dead, so what’s the point?

“One aspect of the culture is the tendency to attribute to racism all of our deficits. I wouldn’t spent 20 minutes arguing with people who say they can point to racism as the origin of these types of things. They’re probably right. But it’s just not helpful. I’d much rather spend my time talking to people who can see or who want to talk about ways to take the situation that exists and improving it for the children.

“It’s not racism that’s keeping our children from learning, it’s something much nearer home than that. I look at what happens in DC schools, where children may go a semester without seeing any white people face to face. I’m just not prepared to argue on their behalf that racism is what keeps them from achieving in school. If education is not happening, I’m inclined to look at the mix of things we have rather than at some external enemy to figure out why.”

His trip back to Okolona is about figuring out solutions.

The sign on the two-lane road south of Tupelo reads OKOLONA–THE LITTLE CITY THAT DOES BIG THINGS. The town once had a stoplight, Raspberry says, but now there is only a four-way stop at the intersection where a left turn takes you into the downtown area.

There isn’t much to downtown. It is a two-block row of mostly one-story buildings, many of them empty. The lettering on the glass door of one of the buildings reads CITY HALL. Next door, in a large room called the Rockwell City Auditorium, a group of women is preparing for Raspberry’s talk. On a long table in the back of the room are platters of fried chicken, barbecue, spaghetti, and hot dogs. There are two sheet cakes for dessert. One reads “Welcome Mr. Raspberry From the Area Day Care Centers”; the other, “Best Wishes From Jolly’s Chapel Church.”

Tables covered with white paper tablecloths are arranged diagonally in the room. At the center of each is a glass vase with small bunches of garden flowers. Many of the people gathering for the presentation don’t know Raspberry, but they know he is probably one of the most famous citizens ever to come out of Okolona.

Two television crews have come in from Tupelo, as have a reporter and a photographer from the Northeast Mississippi Daily Journal. More than 150 people occupy the room. There are parents with children, representatives from local daycare centers, the mayor, the chief of police, city-council members, the local superintendent of education, the state superintendent of education, and a committee chairman from the state legislature.

It takes a while to get to the main event. Children lead the crowd in reciting the Pledge of Allegiance and singing “God Bless America.” There’s a round of welcoming speeches and thank-yous. Raspberry had planned on paying for the kickoff supper, but local organizers raised the money themselves, so there are acknowledgements to the benefactors–the Bank of Okolona, the Tennessee Valley Authority, People’s Bank & Trust, Chandler’s Furniture Center, Scott’s Auto Parts–and special thanks to area churches.

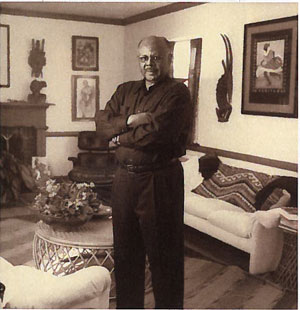

Finally, Bill Raspberry, dressed in a short-sleeve black shirt and tan pants and wearing a HELLO MY NAME IS tag, rises to speak. He is a solidly built man, balding with a neatly trimmed moustache, and his years of speaking are evident. He spends two days a week at Duke University, where he teaches a public-policy course.

Standing in front of an American flag and a Mississippi state flag–with the stars and bars of the Confederacy in one corner–he tells the audience that his goal is to make Okolona’s children the smartest in Mississippi. That will take some doing. Earlier this year, some parts of Mississippi had seen modest improvements in students’ scores on standardized reading and math tests. Chickasaw County, however, had experienced the state’s steepest decline. (A member of the Okolona chamber of commerce said the local high-school dropout rate is a staggering 58 percent.)

Raspberry explains that his program will begin with “baby steps.” It will focus first on preschoolers–more precisely, on the parents of preschoolers. He calls on the audience to join him by showing up for a special training program the following Monday to learn how to help parents help their children and to form a cadre to help train other adults and parents.

“When it comes to our schools,” he tells the crowd, “we demand that George W. Bush live up to his promise of ‘no child left behind.’ We demand that the governor and the state superintendent of education and the local school system and the chairman of Ways and Means do what is necessary to provide our children the educational resources they need.

“And we have a right to do that. But while we are demanding that others do their jobs, we need to do ours. We need to remember that the most influential resource a child can have is a parent who cares. And we need to admit that sometimes parents are the missing ingredient.”

He says it is important for parents to talk to their children, not to “grunt or holler” at them, and to compliment them regularly.

“We black parents sometimes get into the habit of thinking we can beat our children into proper behavior, that we can yell and scream them into doing the right thing, that we can intimidate them into virtue,” he tells his audience. “The more you compliment them for what they do right, the less you have to yell at them for what they do wrong.”

He finishes to a standing ovation. Adults form a line to sign up for the training session the following Monday.

Raspberry admits that he has no idea how successful his program will be. He knows it will take time, but exactly how long–and how great a financial commitment–he isn’t sure.

This much he does know. “The great secret of middle-class existence in this country is that you don’t have to be really smart to make it. Poor people often don’t understand that, but the middle class understands it well. They know that their children of quite ordinary intelligence, if you get them into the right academic situation, they’re not all going to Harvard, but you can get them somewhere and get them in the right professions, they’ll do okay.”

Raspberry has a two-year commitment on his teaching contract at Duke. He says he probably will keep his weekly Post column going at least that long. But he’s on his Mississippi mission for the long haul.

For Raspberry, reviving the academic spirit of Okolona College is vitally important. “If the column gets in the way of doing what I want to do in Okolona,” he says, “I’ll leave the column.”

This article appears in the December 2003 issue of The Washingtonian.